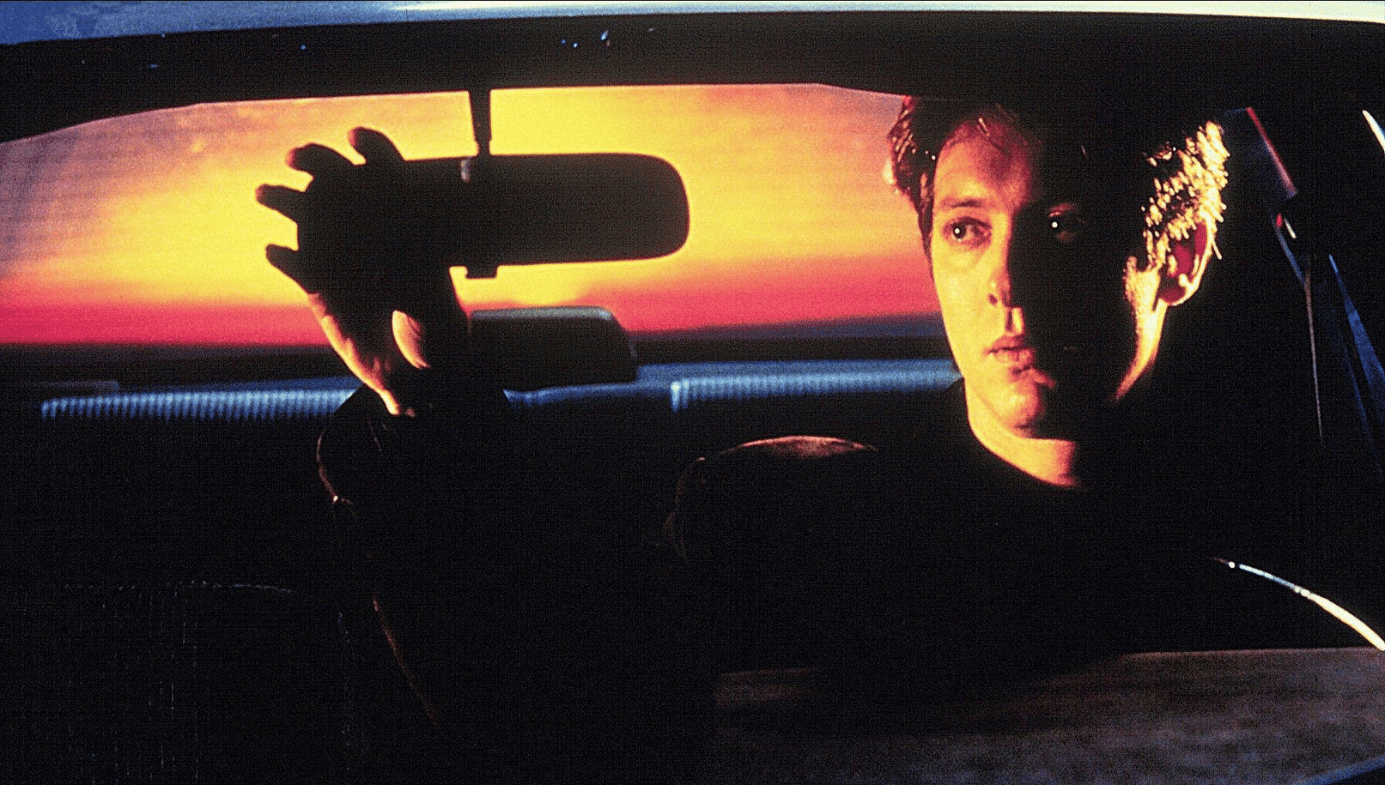

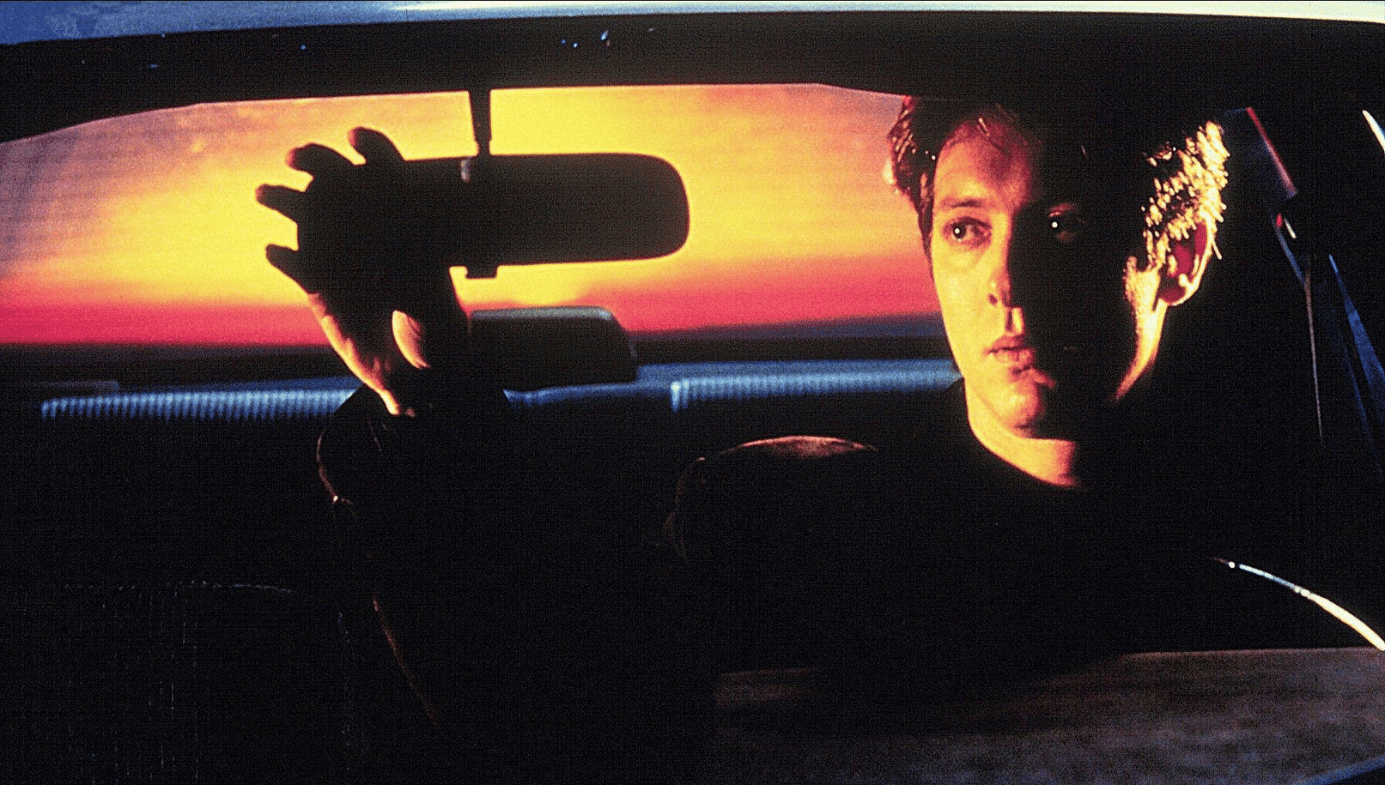

Sex and Smashed Steel

A look back at J.G. Ballard's ‘Crash’—one of the the 20th century’s greatest and most disturbingly prophetic novels.

A look back at J.G. Ballard's ‘Crash’—one of the the 20th century’s greatest and most disturbingly prophetic novels.

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.