Nations of Canada

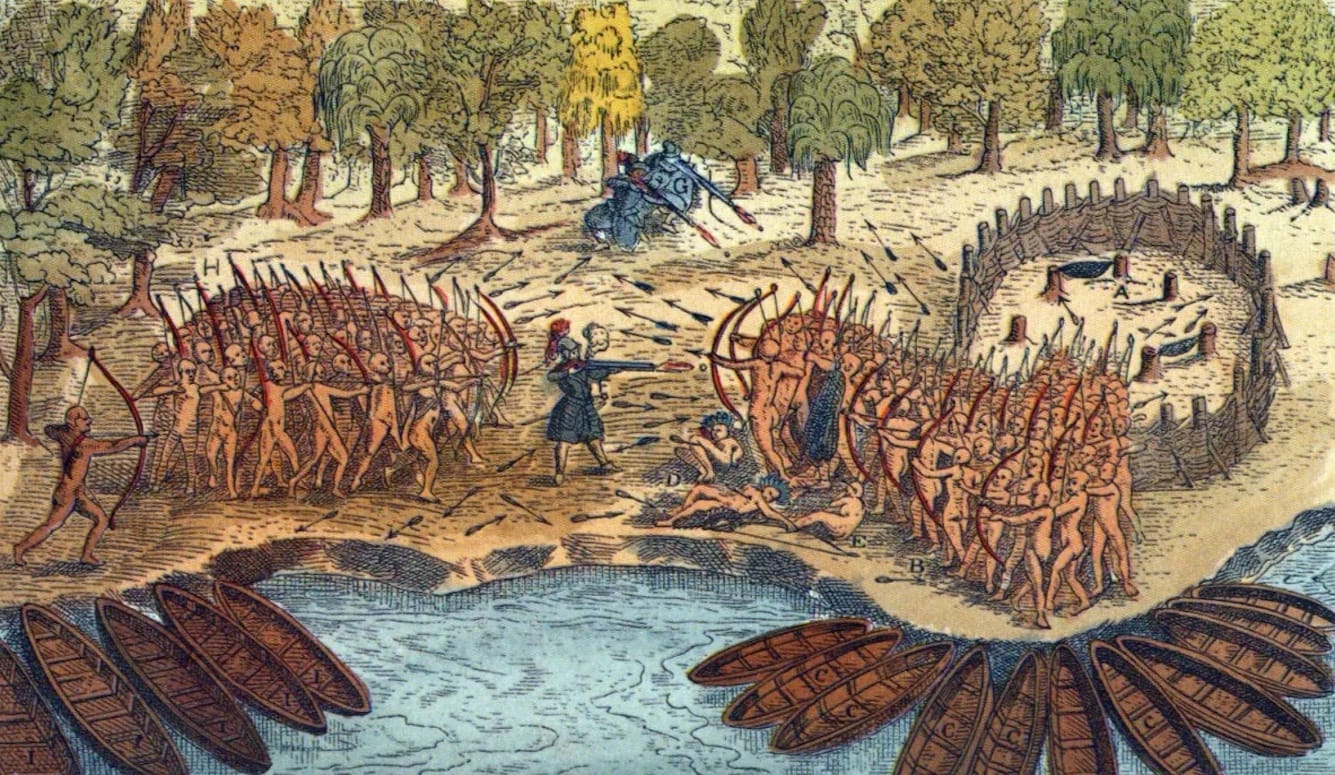

A Different Way of Fighting

In the eighteenth instalment of ‘Nations of Canada,’ Greg Koabel describes the confusion that resulted when French and Indigenous fighters jointly assaulted an Iroquois village in 1615.

· 29 min read

Keep reading

Natalism and the Welfare Mother

Stephen Eide

· 6 min read

A New Middle East?

Brian Stewart

· 6 min read

Greta Thunberg’s Fifteen Minutes

Allan Stratton

· 10 min read

Gentrifying the Intifada

John Aziz

· 8 min read

Creative Writing in the Age of Trump

Daphne Merkin

· 7 min read