Politics

A Revolution on Race?

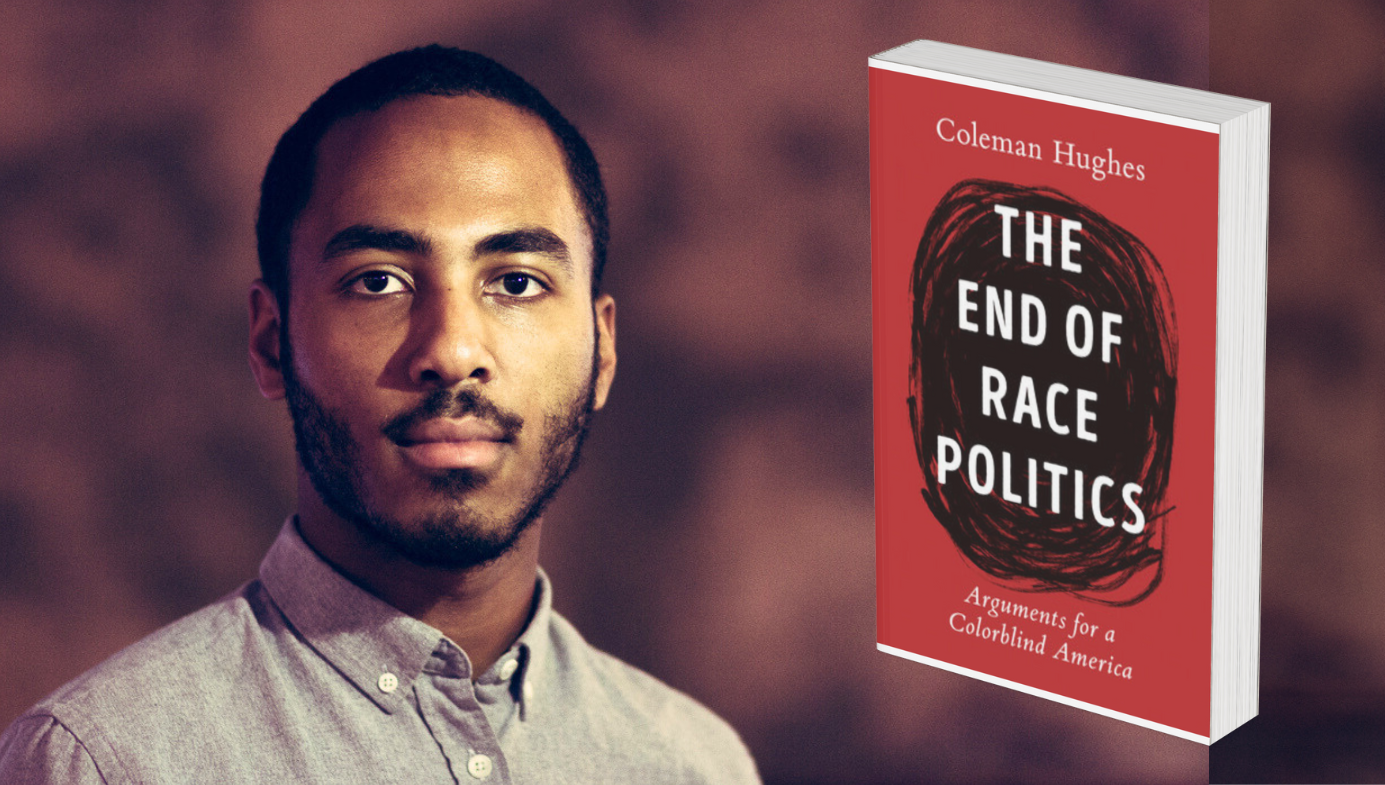

With ‘The End of Race Politics,’ Coleman Hughes enters the ranks of the most mature and sophisticated analysts of the all-American skin game.

A review of The End of Race Politics by Coleman Hughes, 256 pages, Penguin Random House (February 2024)

In 1930, the radical Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci wrote: “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.” In an age when the atomization of identity politics is evident in every corner of American society, it is worth asking whether a similar phenomenon is at work in the politics of race. The old ways of thinking and talking about race certainly appear to be dying out. But it seems premature to declare the birth of an enlightened new order just yet.

Coleman Hughes is a New York-based writer, podcaster, and musician who believes that the morbid symptoms of this corrupt and corrupting ideology are unmistakable, and that the current interregnum therefore ought to be given an overdue burial. In The End of Race Politics, Hughes sets himself a double task. First, he attacks the “reverse racism”—which he simply calls “neoracism”—that has spread into the body politic. Second, he sets out the positive “arguments for a colorblind America.”

Hughes begins his broadside against the fashionable fixation on race with a frank admission that he always found the topic of race “boring.” In our present climate of passion and hysteria around the subject, this simple assertion is a blast of fresh air. It will no doubt be met with outrage by race supremacists and race obsessives alike. In certain quarters it will even be treated as an unpardonable heresy—not merely a profession of unbelief, but an act of apostasy from a black writer. But to paraphrase Emerson, if there is any meanness in Hughes’s argument, it is joined with a certain superiority in its fact.

Born in the final decade of the 20th century, Hughes came of age in a country that had largely triumphed over the prideful bigotry that had stamped it for most of its existence. Many in his generation instinctively agreed with Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous dictum about the content of one’s character trumping the color of one’s skin. Following a shameful history of slavery and segregation, the United States had transformed itself and rooted prejudice is no longer an obstacle to black achievement. In modern America, race itself has become banal. For Hughes, as for most of his contemporaries, skin color had become “a meaningless trait.”

But in parts of our agitated academic culture, race was still vested with almost cosmic importance. In 2012, Hughes encountered this idea—he justly calls it an ideology—for the first time as a high-school student when he attended the People of Color Conference. This “critical race theory and intersectionality workshop,” as he describes it, introduced Hughes to notions that were then on the fringe but would soon make their way to the center of American life, infecting “all of our key institutions: government, education, and media.”