Beware the Little Lambs

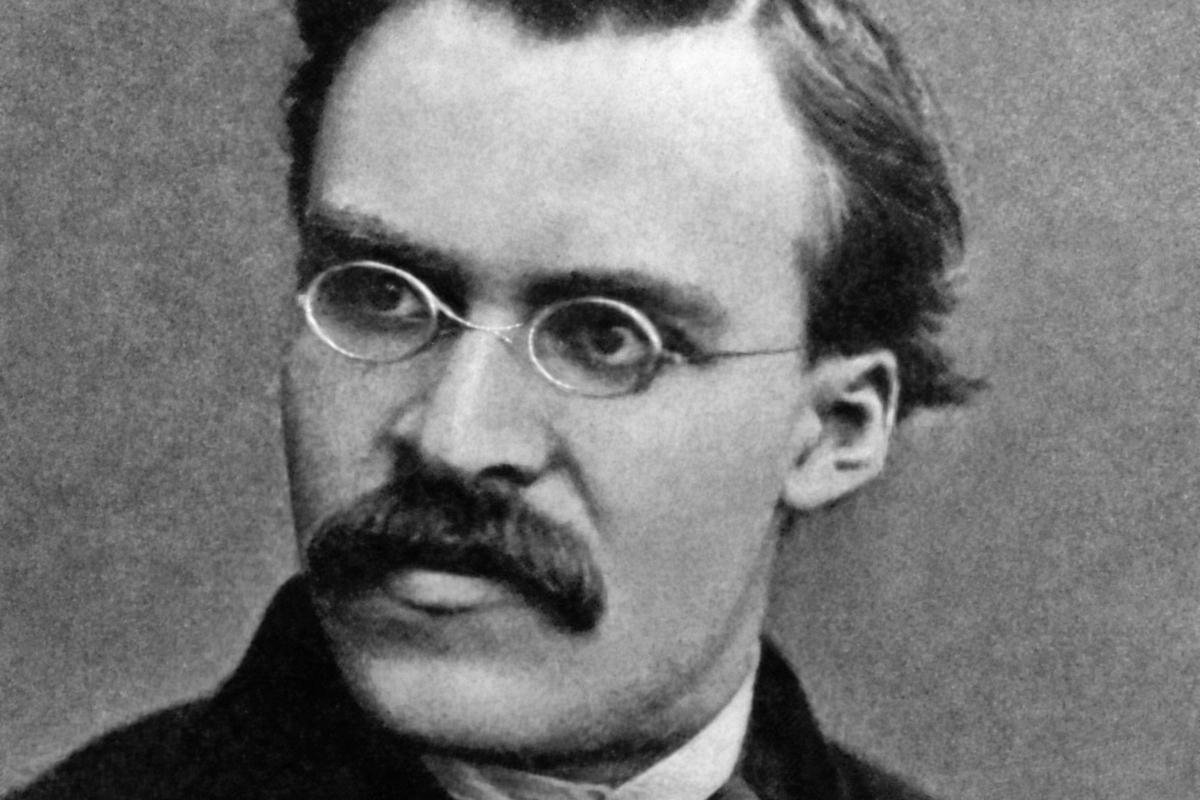

Nietzsche warned us about the dangers of defining our values in opposition to something else.

In a recent interview, Elon Musk remarked that American values have reversed, from “might makes right” to opposing strength and regarding weakness as a virtue:

It really has come completely full circle from—or 180 degrees from—what has historically been the case. Through most of history the operating principle has been “might makes right.” ... Now we’ve sort of flipped it to “if you’re weaker, you’re right.” But neither is true. There is rightness independent of strength or weakness. Just because someone is strong, doesn’t mean they’re right, and just because someone is weak, doesn’t mean they’re right.

Musk seems to be pointing to one example of a larger trend in our society, where it’s increasingly common to define oneself—or a movement, campaign, value system—in opposition to or as a reversal of something instead of towards something positive in its own right.

We see this in every corner of our political discourse: anti-capitalism, anti-wokeism, anti-racism, anti-Zionism, anti-fascism, anti-immigration, never-Trump, cancel-culture, anti-vax, techlash. The problem is not that these positions are necessarily incoherent or wrong, but when adopted in the absence of positive values—without an internal inspiration that moves us towards one possible world over another—we lose the ability to grapple with complexity, to form nuanced perspectives, or to chart a path from our imperfect world to a better one.

Large Birds of Prey and Little Lambs

Nietzsche wrote extensively about how humans can find themselves trapped in a simplistic moral binary, and in particular, the dangers of defining one’s values in opposition to something else. He describes two kinds of value formation, represented by the “large birds of prey” and the “little lambs.”

The large birds of prey create values spontaneously as a direct consequence of their own experience. A bird “conceives of the basic idea ‘good’ by himself, in advance and spontaneously, and only then creates a notion of ‘bad’”—the positive values of the birds are primary, and “bad” arises only as an afterthought. It is “good” to eat the tasty little lambs because they’re delicious, so not being able to do so is “bad.” There is no need to appeal to a universal morality—the bird weighs the world in relation to its natural inclinations.

The little lambs, on the other hand, are weak and oppressed by the birds, and as a consequence of their weakness, they fail to perceive positive values within themselves. Instead, they develop what Nietzsche called ressentiment—a vengeful hatred towards their oppressors, and this becomes the foundation of their values. Unlike the birds, they lack values of their own, so the lambs do not judge the birds in relation to themselves and their “good.” In a creative act of self deception, they transform their hatred of their oppressors into an external standard or universal value by which they can judge the birds. As Nietzsche put it:

What they hate is not their enemy, oh no! They hate “injustice,” “godlessness;” what they believe and hope for is not the prospect of revenge, the delirium of sweet revenge, but the victory of God, the just God, over the Godless.

Nietzsche uses “God” here, but we could just as easily swap in any appeal to universal morality: human rights, family values, equality, justice, or equity.

For the lambs, evil is the foundation of their morality, and good is the afterthought. The lambs say to one another, “These birds of prey are evil; and whoever is least like a bird of prey and most like its opposite, a lamb, is good, isn’t he?” The birds, on the other hand, don’t mind the lambs at all. They say, “We don’t bear any grudge at all towards these good lambs, in fact we love them, nothing is tastier than a tender lamb.” The fabricated morality of the lambs allows them to convince themselves that they are worthy, righteous, and happy. When used to manipulate others, this becomes a lamb’s source of power.

Nietzsche is not saying that the large birds of prey are good, and that the little lambs are bad. But he encourages us to embrace complexity, see beyond the oppressor/oppressed binary, and avoid uncritical glorification of the oppressed. The birds may be oppressing the lambs, and the lambs have every reason to fight back. The problem for the lambs is that, because they believe virtue and self-actualization lie in being the opposite of a bird, they are prevented from doing the work required to become a thing worthy of their own respect. Self-deception leads to clinging to one’s misery instead of overcoming it—“they tell me that their misery means they are God’s chosen.”

A more authentic and fruitful path would be to acknowledge one’s shortcomings and say plainly, “We weak people are just weak; it is good to do nothing for which we are not strong enough.” Only then can they undergo a process of self-overcoming that allows for the birth of positive values.

Modern Lambs

The human tendency towards ressentiment and its creative expression as a reversal of oppressor values is not new. On the Genealogy of Morality was originally published in 1887, and the ideology Nietzsche attacked was Christianity. Certain aspects of modernity fuel the dissatisfaction and envy that lead to defining oneself in opposition. Social-media algorithms amplify voices of grievance, victimhood, and outrage. Consumer culture motivates potential buyers with appeals to envy and dissatisfaction. Politicians of all stripes motivate voters with appeals to hatred of a perceived oppressor—greedy rich capitalists on the Left, elite globalist snobs on the Right.

In an imperfect world, it is easier to criticize solutions than it is to make pragmatic choices that require taking the least-worst option and making sacrifices along the way to a more positive future. It’s easier to protest than it is to overcome oneself and creatively invent new values that make it possible to navigate the real world. Beyond keeping individuals trapped in resentment and outrage, this reactive morality can be used to justify acts of brutality directed at a perceived oppressor, while masking the true motivation behind such acts. Assuming an identity of “the oppressed” makes it easy for collectives to condone behavior that would otherwise be obviously distasteful.

Today, we see this mindset everywhere. Progressives demand that middle-class workers must lose their jobs over a tasteless joke on social media; Republicans defend their leader’s worst misdeeds in the name of “punching back” at the elite; anti-colonialists defend the rape and murder of Israeli civilians by Hamas in the name of “resistance”; white supremacists justify violence and hate in retaliation for “replacement”; Stalin sought to free Russia from plotting bourgeois capitalists and imperialists; Hitler believed he was fighting a global Jewish conspiracy.

It’s easier to fill the void with outrage, envy, and hatred than it is to truly perceive ourselves and grapple with the world in all its complexity.

The Way Out

In another animal metaphor from Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche charts a path of self-overcoming by which an individual can transcend the reactive values of the lamb, and learn to accept and integrate their true motivations and contradictions. First, one must become a camel by accepting and bearing the burden of whatever traditions, norms, and moral values are imposed by society. The camel must actively engage with these values, because only once they are deeply understood can one recognize exactly what must be overcome. Nietzsche himself deeply studied theology before launching his critique of Christianity.

Next one must become a lion, with the strength to rebel against the old values and create a freedom within which new values might be formed. But just like the lambs, the lion cannot create new values simply by opposing the old. To do that, the lion must become a child, who is innocent, playful, and forgetful, and has the ability to invent new values, new perspectives, and new positive visions of the future—“a holy Yea.” Unlike the lamb, the child’s creation of values is proactive instead of reactive, and rooted in an affirmation of their own existence instead of in opposition to something else.

The world we must navigate is complex and full of contradictions. Simplistic moral reversals feel satisfying and empowering, but they fail to inspire a positive path forward. The world is full of harmful and oppressive forces that must be opposed, but if we let this opposition define us, we stunt any possibility of building towards a future that affirms the world as it is in all its richness and complexity.

This process isn’t easy or formulaic—Nietzsche’s transformation is never complete—but an ongoing struggle of honest self-examination and reinvention. As Nietzsche declared, “‘This is now my way, where is yours?’ Thus did I answer those who asked me ‘the way.’ For THE way—it does not exist!”