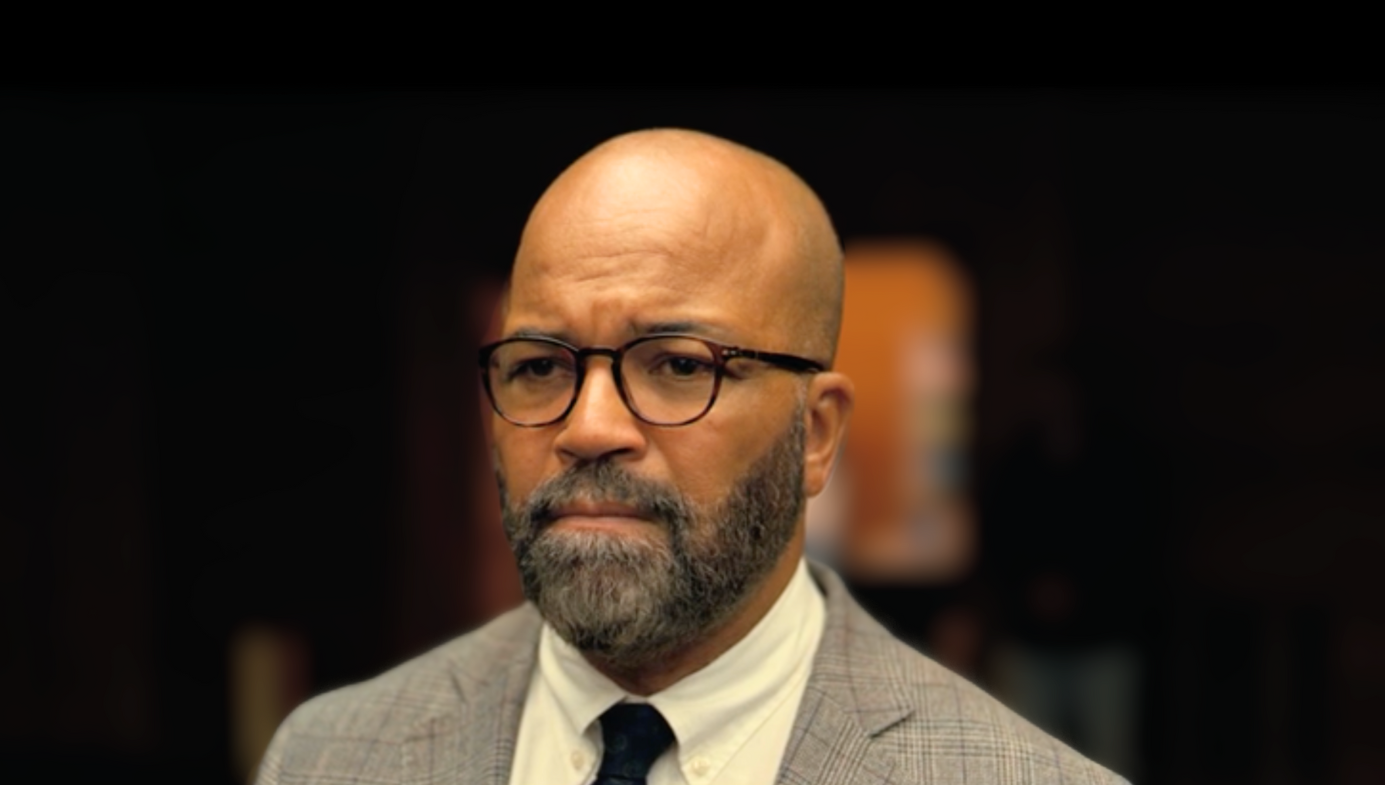

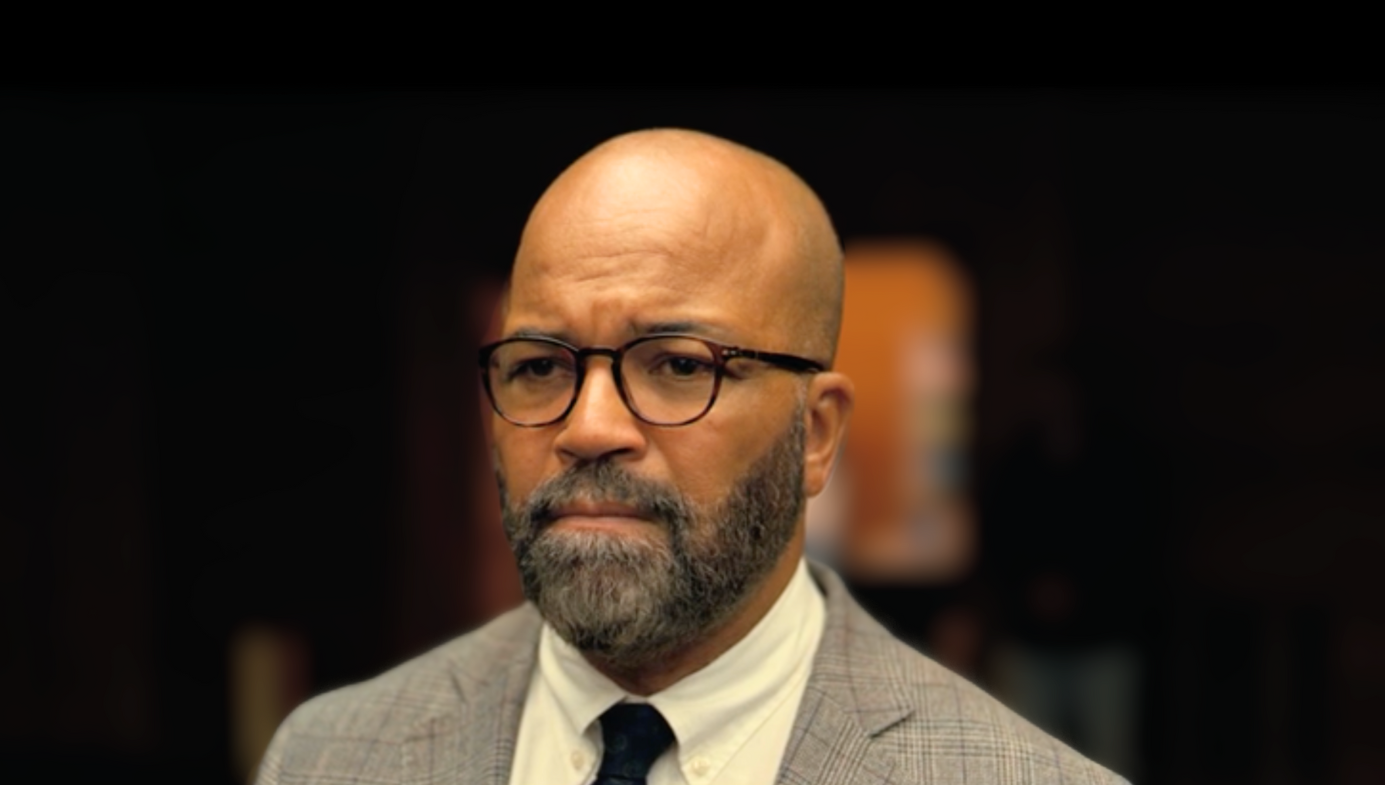

Bestseller Reparations

In ‘American Fiction,’ director Cord Jefferson brings a devil-may-care effrontery to bear on the culture of self-censorship, progressive pieties, and artistic hypocrisy.

In ‘American Fiction,’ director Cord Jefferson brings a devil-may-care effrontery to bear on the culture of self-censorship, progressive pieties, and artistic hypocrisy.

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.