The Elgin Marbles: Playing for Keeps

The Ancient Greek sculptures are a bellwether of where the “decolonization” of museums is headed.

However furious Greece’s Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis may have been, he wasn’t going to show it.

“I certainly want to leave this unfortunate incident behind me,” he told reporters on 1 December 2023, after his UK counterpart Rishi Sunak had abruptly cancelled a planned meeting between the two. “In the spirit of longstanding good relations our two countries have, which I surely intend to preserve, I don’t have much to add.”

Mitsotakis may not have much to add, but the apparent reason for the meeting’s cancellation—the fact that Mitsotakis had openly called for the UK to return the Elgin marbles during a BBC interview of 26 November—has reopened one of the longest-running and most contentious debates about the place of historical artefacts in a postcolonial world.

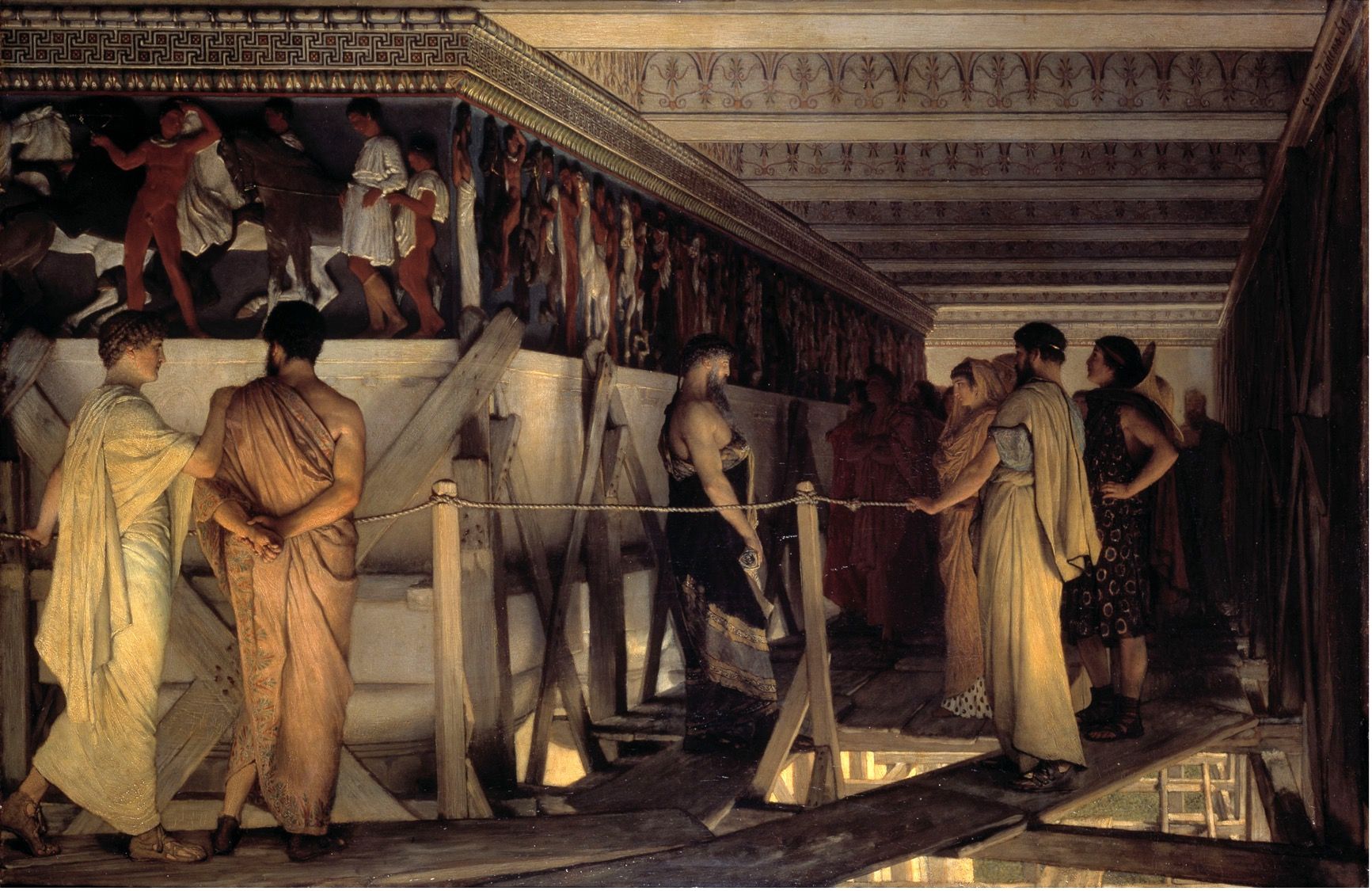

In 1801, Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin, then Britain’s Ambassador Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Ottoman Empire, instructed his agents to begin removing sculptures from the Parthenon and the other ancient buildings on the Athenian Acropolis.

By the time their work was completed in 1812, they had removed more than half of the surviving sculptures on the Parthenon, including some 60% of the frieze, a continuous band of sculpted figures that runs around the outside of the temple’s inner sanctum.

In 1802, one of the first ships transporting the marbles sank off the island of Kythira and its cargo had to be recovered by sponge-divers. Two years later Admiral Nelson helped ship them to Malta, where they spent a few years in dockside warehouses.

Eventually, all the “Elgin marbles” arrived in Britain, where Elgin had already been exhibiting some of them from 1807 on, to a rapturous public reception, in a house in Piccadilly (later the site of the first Hard Rock Café). Elgin’s grand plans to display them in a rebuilt Parthenon, with the help of the superstar sculptor Antonio Canova, came to naught, and in 1816, reeling from an expensive divorce, Elgin sold the marbles to the British government for £35,000—less than half the £74,240 he had spent on their removal and transportation.

The marbles were immediately transferred to the British Museum, where they have remained ever since, except for a spell in the London underground during World War II.

The Elgin marbles have been controversial from the start, even in Britain. Lord Byron laments the “mouldering shrines removed/ by British hands” in his bestselling poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (1812–18). And Parliament’s decision to purchase Elgin’s marbles in 1816 was no foregone conclusion: Sir John Newport, a leading Whig politician, accused Elgin of “the most flagrant pillages” during the debate, and the purchase was ultimately approved by only two votes.

Greece, for its part, first called for the sculptures to be returned in 1836, only a few years after gaining its independence from the Ottomans. Successive Greek governments have demanded their return ever since. The former actress and singer Melina Mercouri’s campaign as Minister of Culture culminated with the country’s formal registration of a claim with UNESCO in 1984.

So far, the British government has always refused to comply, relying on the finding of a 1816 parliamentary select committee that Elgin had acted legally, and on the British Museum Act 1963, which requires the British Museum to “keep the objects comprised in the collections.”

In February 2023, there were reports of secret meetings between Mitsotakis and George Osborne, the former UK Chancellor who is now Chairman of the British Museum. Hopes for an agreement—perhaps involving a long-term loan of the marbles to Greece—ran high, especially in Greece. When Sunak cancelled his meeting with the Greek Prime Minister in December, following Mitsotakis’s interview, these hopes were dashed.

The arguments of both parties have remained similar (with some differences in emphasis) for decades.

In his BBC interview, Mitsotakis emphasized that the Parthenon sculptures should be viewed together, as part of a single artwork. “If I told you [to] cut the Mona Lisa in half…, do you think your viewers would appreciate the beauty of the painting?” But this argument is hardly decisive on its own—after all, the marbles could all be displayed together in London or at a neutral venue.

However, the Greeks now have a powerful additional argument in the form of the Acropolis Museum, whose top floor houses the marbles still in Greece arranged exactly as they would have been on the Parthenon—with the temple itself fully visible to viewers only a stone’s throw away.

The new Acropolis Museum has invalidated one of the British Museum’s key arguments for keeping the marbles—that the Greeks had nowhere to house them. (Everyone agrees that it’s too risky to place the marbles back onto the Parthenon itself, and a previous museum on the Acropolis was notoriously cramped.) It has also put paid to the idea that only the British Museum can properly safeguard these artistic treasures, which were designed and shaped under the direction of the great Phidias.

Some of the sculptures Elgin left on the Parthenon did subsequently disappear or were damaged by Athens’ polluted air; but the marbles he brought to London also suffered damage, both from London’s air pollution and from a series of controversial attempts to clean them. And while it’s true that a cash-strapped Greek state often struggles to take proper care of its huge and varied inheritance of artefacts and remains, no one now seriously doubts that Elgin’s long-contested marbles would be taken very well care of indeed were they transferred to Athens.

On the other hand, the British Museum still offers cost-free entry to the general public, unlike the Acropolis Museum, and currently welcomes three times as many visitors each year as its rival. But there are more important, philosophical arguments for keeping the marbles in London.

The most important of these is the idea of the “encyclopaedic museum”—a repository of objects from different cultures and times, which tells a story that cuts across today’s national boundaries. This model is often contrasted with a more ethnocentric approach, in which all historical artefacts must be returned to the countries they came from—an approach that British critics say underlies Greece’s claims to the Elgin marbles.

The logical consequence of this second approach would be a world in which artefacts were only viewable in the country in which they were produced. This is surely an unattractive prospect. This project would also throw up a host of problems, including in Greece. Do the treasures of the non-Greek Minoans belong in Athens or Crete, for example, and should the great altar of Pergamum, now in Berlin, be “given back” to Greece, or to Turkey, where the ruins of Pergamum are located?

One reason why it has been so difficult to arrive at a resolution in the case of the Elgin marbles is that they are now so high-profile that a decision to hand them to Greece would constitute a decisive blow against the encyclopaedic museum and in favour of the “repatriation” of the world’s cultural artefacts. If this happened, the writing would be on the wall for all the great global museums, from the British Museum to the Louvre (which also holds a few sculptures from the Parthenon). They wouldn’t stand empty anytime soon, but their prospects would not be promising.

In addition, any rapid slide towards returning cultural treasures to the geographical areas in which they were originally found might undermine an important difference between simple theft and the legitimate acquisition of antiquities and other artefacts.

There is an overwhelming case for the return of some artefacts, such as the Benin bronzes (essentially taken by conquest by British colonial forces). Another such case is that of the drawings belonging to Holocaust victim Arthur Feldmann which the British Museum acquired from the Nazis and recently returned to his relatives after Parliament created an exception to the 1963 Act for artefacts obtained between 1933 and 1945.

But despite such cases, the great bulk of the objects in the world’s major museums (including the British Museum) have been acquired in legitimate ways.

Sometimes an object is sold directly to the museum by its discover and/or the owner of the land on which it was found; for example, the Bronze Age Ringlemere cup, unearthed by amateur metal detectorist Cliff Bradshaw in 2011, was later bought by the British Museum for £270,000, half of which went to the owners of the site where the artefact was discovered. More often, there is a more complex but traceable chain of custody, consisting of traders and collectors through whose hands the artefact has passed before it arrived at the museum.

However, an object’s provenance (its ownership history) may be convoluted, may involve unsavoury characters, and there may be several troubling gaps in the story of how it got from its provenience (place of discovery) to the museum in which it is now located. Many of the artefacts that have been flagged for “repatriation” campaigns have unclear provenances. There are often unanswered questions as to how an original owner obtained an object, who has owned it since then, and how it changed hands from one owner to another.

In the case of the Elgin marbles, the chain of custody is a very short one. If the sculptures were legitimately owned by Elgin, they are legitimately owned by the British Museum now. If they were his property, he had the right to sell them to the museum.

So, did Elgin acquire his marbles legitimately? It all comes down to a document Elgin claims to have been sent by the Turkish authorities, which—in his view—granted him permission to take what he took from the Acropolis. This is assuming, of course, that we accept that the Ottoman Turks were the effective owners of the Parthenon. (As Greek commentators occasionally like to remind us, Greece was an occupied territory at the time.)

In his address to the parliamentary select committee in 1816, Elgin claimed that a firman—an official edict of the Ottoman state—authorized his actions. But nearly everything about this claim is up for debate.

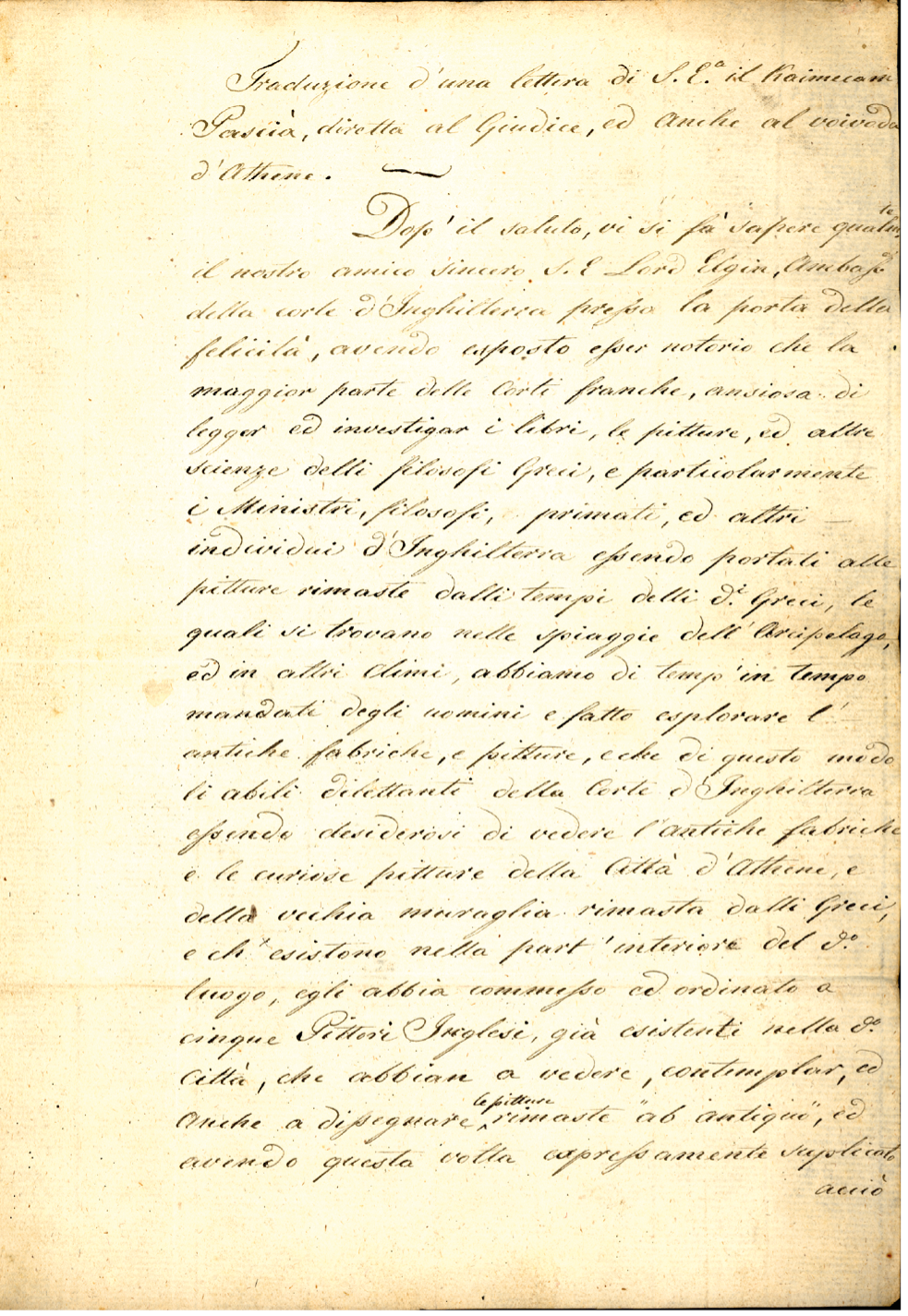

The document itself has not survived and what Elgin presented was in any case not the original but an Italian translation of a letter that may not have been a firman at all but a lower category of official letter, which didn’t have the force of law. And even that document may not have authorized Elgin to remove sculptures from the Parthenon.

The document, signed by a kaymakam (an official who could deputize for the Grand Vizier) and addressed to “the Governor of Athens,” explains that “the skilled dilettanti” (amateur art historians and archaeologists) “of the Court of England” are “desirous to see the ancient buildings and the curious images” of Athens, including the Acropolis, and that to this end, Lord Elgin has commissioned “five English painters… to observe, study, and also draw” the sculptures.

In view of this, the kaymakam instructs the governor not to impede Elgin’s men in going in and out of the Acropolis, “setting up ladders,” making plaster casts of the sculptures, “measuring the remains of other ruined buildings,” or digging into the foundations “when necessary... to find inscribed blocks that may have survived.” He adds, fatefully, “that no opposition be made when they wish to take away some pieces of stone with old inscriptions and figures.”

Does this authorize Elgin to remove sculptures from the buildings themselves, the Parthenon in particular? It seems likely that when the kaymakam licensed Elgin to remove “some pieces of stone with… figures,” he meant pieces of stone that were already lying on or beneath the ground. But the document doesn’t make that explicit, and it may be that Elgin was acting—or thought he was acting—within the letter of the law, if not in its spirit.

Elgin also argued that the Ottoman authorities had demonstrated their consent to the removal of the marbles by cooperating with him and his agents. As he put it, “the thing was done publicly before the whole world... and all the local authorities were concerned in it, as well as the Turkish government.”

This has become an increasingly important argument for the British Museum. In 2009, then-director Neil MacGregor stated that “there’s no question” that Elgin’s actions were legal “because you can’t move those things without the approval of the power of the day… it was clearly allowed, or it wouldn’t have happened.”

As those in favour of the marbles being transferred to Greece often point out, Elgin and his men handed out substantial bribes to the Turkish officials involved—but bribes were often required to get Ottoman officials to do what they had already been instructed to do by their superiors, so this doesn’t necessarily indicate that the Ottoman state was opposed to Elgin’s actions.

The question of ownership of the marbles, then, is still unresolved.

The British Museum and successive UK governments have consistently reiterated the findings of the 1816 select committee and refused to enter into any arrangements—including the loan of the sculptures to Greece—that do not acknowledge what they see as their rightful ownership.

The Greeks, however, have always felt that the marbles are rightfully theirs, even if they have argued that they should be returned on other grounds, too—as Mitsotakis did in his BBC interview. “This is not a question of returning artefacts whose ownership we question,” he said, though he added that “we feel that these sculptures belong to Greece and they were essentially stolen.”

In 2013, almost twenty years after first lodging its claim with UNESCO, Greece asked the organization to mediate its dispute with the UK, but the British government and British Museum refused to accept UNESCO’s mediation. In 2021, UNESCO called on the United Kingdom “to reconsider its stand and to proceed to a bona fide dialogue with Greece.” But the name of the body that issued the appeal—the Intergovernmental Committee for Promoting the Return of Cultural Property to its Countries of Origin or its Restitution in Case of Illicit Appropriation—raises questions about its neutrality.

In December 2022, then Culture Secretary Michelle Donelan appeared before another UK parliamentary select committee, more than two hundred years after Lord Elgin did. Asked about the marbles, her response was a smorgasbord of different arguments, from appeals to ideas of custodianship and the encyclopaedic museum to questions about how we can even know, in this and comparable cases “who we give these things back to.”

Most importantly, Donelan asked pointedly, “Once you start giving one back, where does that end?” Returning the marbles would, she claimed, be “a very dangerous and slippery road to embark down.”

This is surely right. The Elgin marbles are a bellwether of where the debate over “decolonizing” museums is headed. If they leave, other artefacts will surely follow—not only from the British Museum, but from the Louvre, the Met, and elsewhere. That risks not only burying the idea of the global museum, but casting doubt on the entire antiquities market, as well as on property rights in general.

There may be a way, however, for the case of the Elgin marbles to be handled that does not lead to a complete emptying of the world’s encyclopaedic museums or a body blow against important legal principles. This would involve both parties agreeing to submit to a finding on the legality of Lord Elgin’s original appropriation of the marbles, and hence on whether the British Museum does in fact legitimately own them.

The finding would have to be made by a body august enough to be respected by both parties and recognized by the international community—and it would also have to be seen to be unbiased. Both parties would have to agree to abide by the committee’s decision.

If it found that Elgin took control of the marbles legally and that the British Museum is therefore their current legitimate owner, a long-term loan to the Acropolis Museum could be arranged. If the committee found instead that Elgin never legally owned the marbles, and that the British Museum thus does not own them either, the UK government could surely expand their exception to the 1963 Act (passed to allow the return of artefacts taken by the Nazis) so that it could return other objects found to have been improperly acquired, including the Elgin marbles.

None of this would be easy. It would involve a thorough vetting of candidate organizations for a complex legal and historical investigation that would probably take years. Given the strong feelings on both sides, the stakes would be high—one of the two parties would end up losing not only its marbles, but a considerable amount of face.

Given current technology, some people might suspect that this whole debate is beside the point. When Elgin took his marbles to London, only a tiny minority of people would have been able to view any part of Phidias’s sculptural masterpiece live or even to see drawings of them in expensive books.

Today, high-resolution images from every conceivable angle are a Google Image search away. Both the British and Acropolis Museums offer 3D scans of every sculpted block of marble that ever adorned the Parthenon. And this year the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports and the telecom company Cosmote jointly launched a new app that enables visitors to point their phones at the buildings on the Acropolis and see them as they would have appeared in the Periclean golden age, their somewhat gaudy paintjob not excepted.

In this context, how important is it, really, to resolve the dispute over what Lord Elgin got up to at the dawn of the nineteenth century, before the modern Greek state even came into being?

Extremely important.

As long as modern Greeks care about their classical heritage, it will be difficult for them to accept the idea that treasured artefacts central to their national story are housed in a foreign museum. On the other hand, we cannot allow nationalist sentiment—however understandable—to take precedence over property rights and the rule of law.

We need to settle this question legally once and for all—if only to cement the cordial relationship between Greece and the UK, a relationship that has been going strong ever since Britain assisted Greece in its War of Independence. Luckily, this seems to be an aim close to Mitsotakis’s heart.