Politics

A History of Feminist Antisemitism

The story of how activists and academics exchanged the struggle for universal female improvement for a politics of division and hatred.

I. It Wasn’t Always Like This

In my academic life, I was fortunate to have my rabbi teach my first Women’s Studies course and Angela Davis teach my second. At Vassar during the multiculti-and-identity-obsessed 1990s, I learned from Rabbi Shirley Idelson about intersectionality and black feminism, and I was taught that if I didn’t understand the Spanish in the now-canonical anthology This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, I had to find someone who did to translate it for me. I also learned that I could be a Jewish feminist, parsing my own complicated personal and communal history for theoretical insights, in the manner of my favorite theorist, Adrienne Rich.

During my 13 years as one of the only Jews in the Catholic schools I attended, the boy I sometimes thought was my boyfriend drew swastikas on my book covers. The boss at my summer job was delighted to learn that I was going to Vassar, “even though there will be a lot of JAPs there” (a JAP, she explained, is a Jewish American Princess). I didn’t write about the panic of coming-of-age at a time—and in a city—where Operation Rescue picketed abortion clinics and screamed at “baby-killers” every weekend. (A 1990 story in the Jewish feminist journal Lilith was headlined, “The Anti-Choice Movement: Bad News For Jews.”) The year after I graduated—I had already fled to New York City—Barnett Slepian, a local Jewish doctor who performed abortions, was assassinated by a member of a Catholic anti-abortion group upon his return from shul.

Nevertheless, in my first paper for Rabbi Idelson’s class, I compared my own experience of racism to that of black Americans and concluded that American blacks had it worse. “I think you mute the terror of the swastika,” Rabbi Idelson remarked as she awarded me an A-/A. Later, in Professor Davis’s class, I learned that the term “women of color” wasn’t about melanin, it was an imaginative political formation. Those two classes informed everything I have done since: my undergraduate degree in Women’s Studies; my years as a feminist journalist and book author; and the doctorate I received two years ago, when I finally completed my dissertation on feminist historiography.

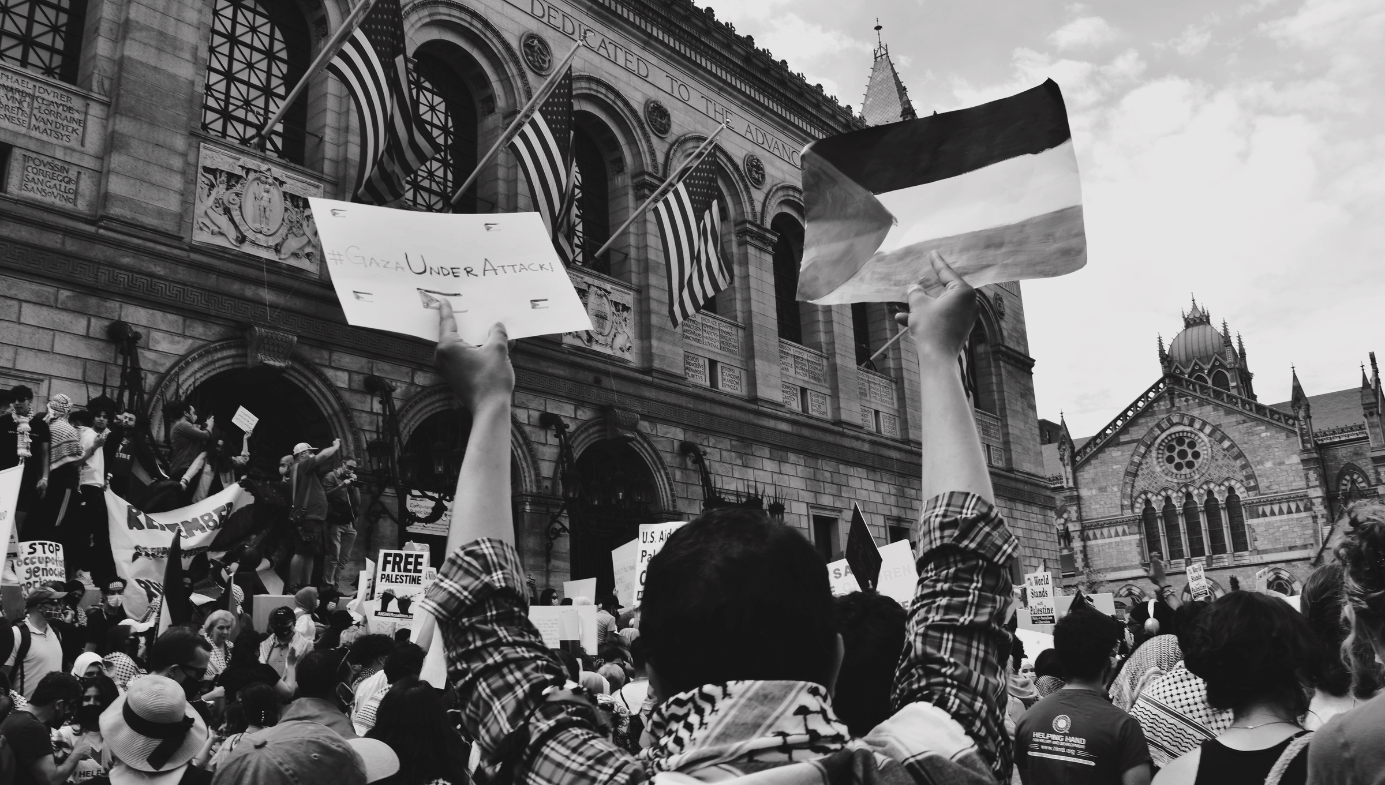

May 2021 was a sad and scary month to be a Jewish feminist, as violence escalated in the Middle East and in New York City, where I still live. Friends from graduate school and the feminist internet posted anti-Zionist infographics on social media and a counterterrorism unit kept watch in front of my daughter’s Jewish nursery school. The morning of my graduation, I awoke to a petition circulating on Twitter titled, “Gender Studies Departments in Solidarity with Palestinian Feminist Collective.” It informed me that Jews are colonizers not indigenous to Israel and rejected the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s definition of antisemitism. Two days later, I received an email from my department with news of an award, and another professing solidarity with the Palestinian people. It was hard to understand exactly what that meant—who doesn’t want a better life for Palestinians?—but given the department’s politics, I could guess.

But this was only a prelude of what was to come after the atrocities committed by Hamas against the kibbutzim of southern Israel on October 7th. Around 1,200 men, women, and children were murdered and a further 240 were swept into captivity and an uncertain fate in Gaza. But before the bodies of the dead were even cold, progressive friends and colleagues were posting images of Palestinian flags and paragliders on social media, and redescribing the aggressors as victims.

More shocking still was the feminist response to reports of torture and sexual cruelty that began to emerge in the wake of the massacre. Many feminists were either reluctant or defiantly unwilling to show the slightest solidarity with Israeli women. Their priority lay instead with supporting calls to “decolonize Palestine” by “any means necessary.” Rape and sexual assault were now either scorned or denied, and in some cases even excused as the legitimate—or at least understandable—acts of an oppressed people. There is no obvious reason for feminists to support Hamas over Israel given the regressive ideas about female liberty and gender roles set out in the former's foundational covenant. And yet, some feminists attended demos against Israel at which eliminationist slogans were chanted, while others vandalised posters of the missing in the name of a free Palestine. Even the UN Women’s Council dragged its feet, taking eight weeks to condemn Hamas’s sexual violence.

It wasn’t always like this. In the years before the Second Intifada began in 2000, magazine and newspaper articles, books, and conference panels proliferated on Judaism and antisemitism. Jewish feminists expressed their love for Israel, or at least an acknowledgment that the country needed to exist. And when criticisms of Israeli policies did surface, they often came from Jewish feminists themselves, who had no difficulty distinguishing Israeli citizens from the actions of their government. “Jewish lesbian-feminists cannot help but feel critical toward the present Israeli government,” wrote Evelyn Torton Beck, a Women’s Studies professor and child Holocaust survivor, in Nice Jewish Girls: A Lesbian Anthology, published in 1982. “In my writing and my activism, I support both the Palestinian and the Jewish national movements,” wrote Elly Bulkin in Yours in Struggle: Three Feminist Perspectives on Anti-Semitism and Racism, published in 1984.

But changes in feminism’s in-group formations and theorizations enabled the antisemitism and anti-Zionism that were latent at the advent of the movement to become salient and entrenched. The shift to identity-based feminism—which includes the women-of-color feminism and queer theory now regnant—has produced some exciting, inventive, moving, and sophisticated feminist theory. But it has also contributed to an ideological climate that scorns discussions of antisemitism and Israel and is now profoundly inhospitable to Jews.

II. From Sisterhood to Identity Politics

Jewish women have been an outsized force in feminism since the 1960s. Florence Howe, who founded the Feminist Press and published lost feminist works by black writers like Zora Neale Hurston, is known as the mother of Women’s Studies. Roberta Salper, who established the first Women’s Studies Program in the country at San Diego State University in 1970, is also Jewish. Many Jewish feminists were writers and organizers: Tillie Olsen, author of Silences; Hélène Cixous, author of “The Laugh of the Medusa”; eight of the 12 members of the original Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, which published Our Bodies, Ourselves; the founder and several members of the Jane Collective, which helped women obtain abortions when they were still illegal. Gerda Lerner, a Holocaust survivor, founded the first graduate program in Women’s History and edited the acclaimed volume Black Women in White America. Shulamith Firestone, who was raised in an Orthodox home, wrote The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution.

In 1963, Jewish labor-journalist-turned-women’s-magazine-writer Betty Friedan kicked off feminism’s second wave with The Feminine Mystique, in which she wrote about the unfulfilling life of a housewife. Younger “radical feminists,” meanwhile, began dissecting sexuality and family life in their consciousness-raising sessions. In 1970, Robin Morgan (also Jewish) wrote:

Women’s liberation is the first radical movement to base its politics—in fact, create its politics—out of personal experiences. We’ve learned that those experiences are not our private hang-ups. They are shared by every woman, and are therefore political.

But the title of Morgan’s anthology Sisterhood is Powerful evokes an overreach that still haunts feminism today. Many Jewish feminists were socialists and staunch anti-racists—expatriates from the New Left and Civil Rights movements, who had taken Black Power’s injunction to “organize among your own” seriously. But their attempts to include women of color in their magazines and conferences were, according to black feminist Toni Cade Bambara, “invitations to coalesce on their terms.”

Most young women had been inspired by the protests against the Miss America Pageant they saw on television, or by the manifestos against housework they read in Ms.. They hadn’t read Marx and Fanon, didn’t know about forced sterilization, and weren’t worried about affording food for their children. They simply wanted to fulfill feminism’s first promise, which was to improve their own lives. And on that front, there was still plenty to do: it wasn’t until the 1970s that unmarried women of any race or class could access the birth-control pill, terminate an unwanted pregnancy, obtain a credit card in their own name, or not get fired for being pregnant.

In the 1970s and ’80s, black, Chicana, Native American, Arab, and Asian women joined together to create a political bloc they called Third World Women, and later, Women of Color. Their texts insisted that oppression was not simply a product of gender, but also of class, race, and sexual orientation. The Combahee River Collective Statement, which introduced “identity politics” in 1977, says, “If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.” The black woman was a messianic figure, and she would bring about world liberation.

Jewish feminists also insisted that they weren’t like other white women, but they were not part of this new burgeoning force. In Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center, published in 1984, black feminist bell hooks writes, “Much feminist theory emerges from privileged women who live at the center.” She was talking about white women in general, and Friedan in particular, whose most famous work hooks described as “a case study of narcissism.” The most visionary feminist theory, she wrote, will emerge from “individuals who have knowledge of both margin and center.” Growing up, Friedan was an infamously hook-nosed intellectual in Peoria, Illinois, rejected by peers because she was Jewish, yet excelling at graduate-level academics at a time when many universities refused to hire Jews. But Jews were not considered marginal; and feminist theory was to be written by—or at the very least about—women of color.

The newest texts, like black feminist Audre Lorde’s 1981 National Women’s Studies Association speech, “The Uses of Anger,” encouraged feminists to redirect anger at men towards one another, a practice This Bridge co-editor and Chicana feminist Cherríe Moraga described that same year as “an act of love.” This ethic of confrontation and “accountability” suffused the lesbian publishing scene that produced the most important feminist theory of the 1980s. In another speech from 1981, titled “Coalition Politics: Turning the Century,” black feminist Bernice Johnson Reagon described the importance of “trying to team up with somebody who could possibly kill you … because that’s the only way you can figure you can stay alive.” This process, she said, caused her to feel “as if I’m gonna keel over any minute and die.” Working together and feeling bad while doing it was the goal. In 1982, Angela Davis told women to become “militant” about racism. It became heroic to be what white feminist Mab Segrest called a “race traitor.”

By this time, Jewish women had started to gain worldly power, and not simply over nannies and housecleaners. Although—and this was the problem—they still had power over nannies and housecleaners, who were often women of color. Feminist publishing experimented with how women could share power. The majority-Jewish editorial collective behind Conditions invited Combahee members Barbara Smith and Lorraine Bethel to guest-edit the 1979 Black Women’s Issue. Bethel opened a poem titled “WHAT CHOU MEAN WE, WHITE GIRL? OR, THE CULLUD LESBIAN FEMINIST DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE (DEDICATED TO THE PROPOSITION THAT ALL WOMEN ARE NOT EQUAL, I.E. IDENTICAL/LY OPPRESSED)” by writing, “Preface: I bought a sweater at a yard sale from a white-skinned (as opposed to Anglo-Saxon) woman. When wearing it I am struck by the smell—it reeks of a soft, privileged life without stress, sweat, or struggle.” A little more than 30 years after the Holocaust, it was not hard to understand who was being accused of easy living here. In 1981’s “The Possibility of Life Between Us: A Dialogue Between Black and Jewish Women,” black women likewise insisted that Jews had it good.

It wasn’t just women of color who decided that Jewish women were too domineering, too successful, too white, too obsessed with the Holocaust, and too interested in their newfound ethnic identity as a way of dominating the newly identity-conscious feminist scene. New-Age feminists believed that Judaism had killed goddess worship, and white Socialist professors equated Jews with capitalists. But Jewish women had once considered women of color to be their natural allies, and now that the feminist theories and alliances of women of color were the most influential, it was their antisemitism that Jewish feminists called out most often. Women of color resented this criticism and said that it was racist.

In 1988—six years after the publication of Nice Jewish Girls, and a year before Kimberlé Crenshaw introduced feminists to the concept of intersectionality—Evelyn Torton Beck complained that Jewish women were being left out of Women’s Studies. She blamed “our initial conceptual framework which established (and quickly fixed) the interlocking factors of ‘sex, race, and class’ as the basis for the oppression of women.” The prevailing analytical framework of Women’s Studies was incapable of acknowledging that conspiratorial suspicions about Jewish advantage and influence actually contributed to their oppression.

Another problem Jewish feminists encountered was growing anti-Israel sentiment, a legacy of New Left and Black Power doctrines that understood the young country as imperialist, despite Jews’ historic ties to the region, and even racist, as though the country’s conflict pit white Jews against brown Arabs, despite the many Jews of color living there. At the United Nations’ International Women’s Year Conference in Mexico City in 1975, delegates—many of whom hailed from Arab and African countries and saw Israel as the United States’ client and a prop for Western hegemony—passed a motion equating Zionism with racism. At Copenhagen in 1980, the conference extended official recognition to the Palestine Liberation Organization’s delegation, headed by famed hijacker Leila Khaled. Israel’s retaliatory invasion of Lebanon in 1982 only increased hostility to Israel on the Western Left, and the brutality of that war made it hard for some Jewish women to defend the country.

Meanwhile, interest in Arab and postcolonial feminism was growing. In a 1983 issue of Women’s Studies Quarterly, Azizah al-Hibri castigated Western feminists opposed to clitoridectomy and the veil instead of occupation, and demanded, “What good is my clitoris if I am not around?” In Yours in Struggle, Barbara Smith wrote, “Often Black and other women of color feel a visceral identification with the Palestinians,” even though, “like many Black women, I know very little about the lives of other Third World women.” The fantasy of an alliance with Third World women was more compelling than the reality of the obstinate Jewish women who had published some (but not enough) books by women of color, whom she publicly rebuked. “I am anti-Semitic,” she declared in the same essay, but she also wrote approvingly of a new and more complex Jewish feminism that supported the existence of Israel while opposing its government. Women of color and Jewish feminists, including Zionists, were fighting in public—but at least some nuance remained, and the two sides were still talking.

III. Bridges to the New Feminist Antisemitism

In 1990, Jewish feminists who wanted to remain part of an increasingly international, multicultural, and intersectional feminist scene launched the aspirationally named Bridges: A Journal for Jewish Feminists and Our Friends. The magazine’s contributors participated in feminist conversations about identity and coalition-building by publishing and reviewing work by women of color, Jews of color, and Israeli and Arab peace activists. Many articles elaborated a formerly latent but now overt new identity: the secular, anti-racist, Jewishly identified, quite-possibly-lesbian feminist who was conversant in women-of-color feminist theory and supported a two-state solution at a time when the Jewish establishment still did not.

But the magazine’s relentless promotion of the Good Jew helped to further demonize the Bad. One writer declared that Jewish women at her college “did not take their studies seriously, chased boys and used their daddy’s charge cards”; another said that she used to read about African Americans “to escape my Jewishness, which seemed distinctly uncool.” The Bad Jews were constantly “harping on” antisemitism and Israel, complained Rabbi Sharon Kleinbaum, the future leader of the iconic gay and lesbian Congregation Beit Simchat Torah.

Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz encouraged Good Jews to weaponize their Judaism against “mainstream” Jews as a feminist act, and to consider the possibility that their charges of antisemitism were “spurious.” Good Jews, she wrote, “have proudly reclaimed a tradition of radical Jews” (one that had nearly vanished because so many socialist, anti-capitalist, anti-Zionist, internationalist members of the Jewish Labor Bund in Eastern Europe were exterminated in the Holocaust). Bridges publicized texts by Jewish feminists instrumental in developing what a 1997 New York Times article called the “new, very hot academic field” of whiteness studies—a discipline that often recasts Jews’ participation in the Civil Rights movement as actually racist because it was paternalistic.

Other changes in feminist politics were also occurring. In 1990, Judith Butler published Gender Trouble, which argued that there is no natural correlation between biological sex and gender expression. “It has become a positive embarrassment to talk about women,” said Women’s Studies professor Nancy K. Miller the following year. Queer theory brought feminists into increasing contact with theorists like Michel Foucault, who questioned individual agency, and they lost interest in lesbian feminism’s emphasis on difficult but potentially productive engagement with opposing views.

In Underdogs: Social Deviance and Queer Theory, queer scholar Heather Love wrote that queer theory’s politics “are split between the liberalism of the civil rights movement and a lumpen appetite for destruction.” This new “queer” identity destroyed identity categories themselves. Love wrote that the vagueness of the term “queer”—sort of about sexual practices, but also not—coupled with the idea that everyone understands it but you, “creates a desire to be ‘in the know.’” Like the cultural ephemera it often turns to as its intellectual objects, queer theory thrived on the transgressive frisson of the unexpected and the illegitimate. If you’re hip, you know that biology has nothing to do with being a man or a woman. You also know that Israel needs to be destroyed.

This combative energy soon became evident in the feminist literature of the early 2000s. The collapse of Israeli-Palestinian peace talks at Camp David, and the ruthless campaign of Palestinian suicide terror that followed, had made many Jewish organizations move rightward. In response, progressive Jews began doing anti-occupation work elsewhere. Meanwhile, 9/11, Israeli military operations in the West Bank, the Bush administration’s wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the Patriot Act, and the debate about Islamophobia all increased American interest in the Middle East. New activist models dispensed with the idea that Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs both had legitimate claims to the land.

In 2003, an essay by Esther Kaplan titled “‘Globalize the Intifada’” appeared in the influential anthology, Wrestling With Zion. Kaplan was a former member of the queer AIDS activist group ACT UP, who succeeded Kaye/Kantrowitz as director of Jews for Racial and Economic Justice. In her essay, she called Palestine “the new cause célèbre” and observed that activists “have replaced the language of ‘conflict’ and ‘peace’ with that of ‘occupation’ and ‘justice.’” Many of these activists now directed their message at non-Jews as well as Jews, an approach Kaplan supported and encouraged:

The time has come when Israel must be totally isolated by world opinion and forced, simply forced, to concede. The road to that victory will be littered with e-mail postings that are a bit strident and flyers that are insensitive to Jewish history. It will be populated by activists who are young, brash and unknowledgeable, a handful of whom will carry placards that read ‘Zionism = Nazism’ in a crude attempt to open old Jewish wounds. Israel will become a punching bag for every good reason and maybe a couple of bad ones, too. And so what?

IV. Feminist Icons: From the Queer Palestinian Terrorist to the Trans Anti-Zionist

“And so what?” The notion that there are bad nationalisms (those allied with the United States) and good nationalisms (those that were going to destroy capitalism and imperialism) was already part of leftist thought. In 2003, Roderick A. Ferguson—a professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Yale, and a future president of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions-supporting American Studies Association—published Aberrations in Black: Toward a Queer of Color Critique, in which he offered this queer-theory-inflected reiteration of one of black feminism’s earliest tenets: “Oppositional coalitions have to be grounded in nonnormative racial difference. … Ours is a moment in which the negation of normativity and nationalism is the condition for critical knowledge.” In 2005, the ultra-hip, ultra-leftist academic journal Social Text published “What’s Queer About Queer Studies Now?,” an essay that showcased the movement’s turn away from “the domestic affairs of white homosexuals” and towards Ethnic Studies and women-of-color feminism.

Feminism further embraced what Love had called queer theory’s “injunction to be deviant.” Jasbir K. Puar’s 2005 essay, “Queer Times, Queer Assemblages,” celebrated the Palestinian female suicide bomber, whose “dispersion of the boundaries of bodies forces a completely chaotic challenge to normative conventions of gender, sexuality, and race, disobeying normative conventions of ‘appropriate’ bodily practices and the sanctity of the able body.” These “queer corporealities,” we were informed, undermine the liberal Western tradition because “suicide bombers do not transcend or claim the rational or accept the demarcation of the irrational.” They are the apotheosis of what queer had always tried to be: not so much about sexual identity, but about “resistant bodily practices” and deviance itself—this time, across international boundaries.

The ideal feminist persona had shifted from the educated working woman to the young radical to the lesbian woman of color, and now, to the queer Palestinian terrorist. Meanwhile, Puar and others—including queer activist Sarah Schulman—would denigrate Israel’s “admittedly stellar” treatment of gays and lesbians as “pinkwashing,” a means of distracting the world from its treatment of Palestinians. Feminism’s ongoing antipathy towards truth in favor of exhilaratingly counterintuitive theory, and a new set of desired effects and conclusions, had reached its apogee in attitudes towards Israel.

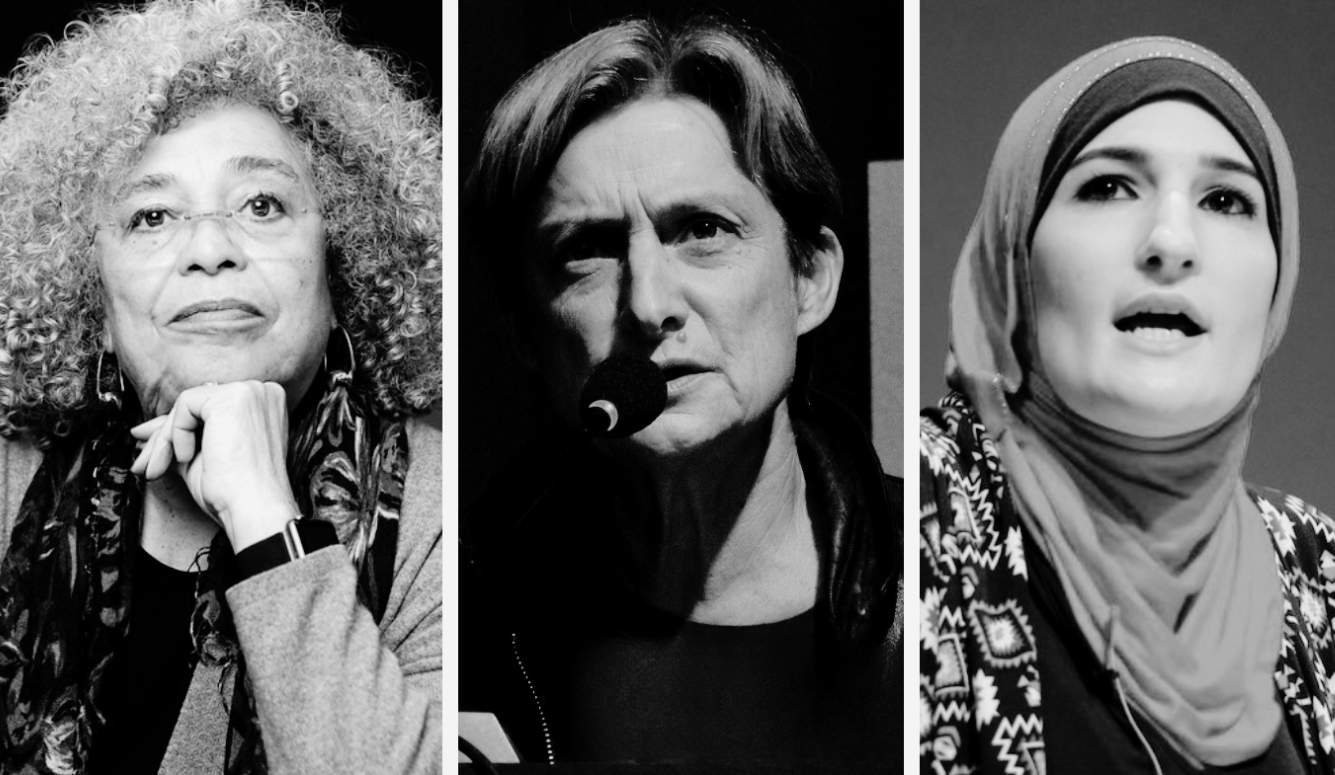

In her 2012 book, Israel/Palestine and the Queer International, Schulman argued that feminist activists don’t need to be experts on the history or the politics of the Arab-Israeli conflict; they could rely instead on the arguments of those she called “credibles.” So, does Angela Davis, who published the 2016 anti-Zionist tract Freedom is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement, qualify as credible? That book was blurbed by Alice Walker—the Pulitzer-Prize-winning black feminist and antisemite—and in her autobiography, Davis recalls how she delighted in Malcolm X’s visit to her college, where he lambasted the white students there (many of whom were Jewish) for enslaving his people. Another work is blurbed by Cynthia McKinney, who recently promoted an unambiguously antisemitic event on Twitter headlined by white supremacist David Duke.

Well, that debate got shut down on all platforms and my notice about it got shut down on "X!" Interesting how the First Amendment now works! https://t.co/e7NSAJz4OE pic.twitter.com/fPiJYkdzuE

— Cynthia McKinney PhD (@cynthiamckinney) September 12, 2023

Schulman, for her part, doesn’t like any Jews who aren’t just like her. She describes a religious woman who wants to help her wash her hands in “that awful Jewish way I remember from my childhood, so invasive you just can’t breathe.” When an Israeli “warmly” invites her to join Jewish Voice for Peace, she “immediately experienced that old recoil. I couldn’t imagine joining a Jewish organization.” Angry at her homophobic, Israel-loving biological family, Schulman acts out queer theory’s celebration of chosen family, imagining a cruel “queer international” in which a sense of belonging is solidified through partying, politics, and Israel-hatred.

Schulman is a seasoned activist—she was a leading member of the Lesbian Avengers—with a bad habit of parroting false history. She describes the diaspora as “natural” and trains the novelistic skills that garnered her a Guggenheim on characterizing Judaism, the Jewish people, and Israel in exhaustively obscene ways. Meanwhile, she fairly swoons when she gets a text that says “we miss you” from some “funny, warm, savvy, sexy, and totally accessible” new Palestinian friends. They take photos together; they smoke pot; they chat about the... what?— transfer? extermination?—of over 7 million Israeli Jews. “We don’t want peace,” they tell her. What will happen to Israelis if her new political project succeeds? “Israel exists,” she says airily.

Schulman worships at the altar of Judith Butler, her number one credible besides her new Palestinian friends. Butler’s 2003 essay, “The Charge of Anti-Semitism: Jews, Israel, and the Risks of Public Critique” (republished in slighted edited form by the London Review of Books under the title “No, It’s Not Anti-Semitic”), is a theoretical rejoinder to former Harvard president Lawrence Summers’s statement that “profoundly anti-Israeli views are increasingly finding support in progressive intellectual communities. Serious and thoughtful people are advocating and taking actions that are anti-Semitic in their effect if not their intent.” Butler’s argument relies on the claim that Summers conflates Jews and Israel and assumes that the effects of antisemitism presuppose intentional antisemitism—which Summers neither said nor implied.

In the years since, Butler and other Gender Studies luminaries have extended their anti-Zionist arguments. Butler, who argues that there is no essence to gender, believes that Jews do have an essence, and that this essence is diasporic (a concept beloved by popular postcolonial theorists like Edward Said and This Bridge co-editor Gloria Anzaldúa). Davis draws parallels between racist police violence in America and the occupation. Puar says that Israel harvests Palestinian organs. For Dean Spade, in his 2011 book, Normal Life: Administrative Violence, Critical Trans Politics, and the Limits of the Law, trans politics are connected to Islamophobia because the United States’ war on terror amplified “security culture,” increasing surveillance policies that disproportionately disadvantage both Arabs and gender outlaws.

For example, a person whose gender expression does not match their sex may experience job discrimination, turn to illegal work, and end up in prison. This feminist anti-Zionism sees the existence of state-sanctioned gender categories as a violence that must be undone, even as it supports physical violence by non-state actors against Israelis. It is against liberalism and against rights, because rights, which are granted by the state, serve to prop up state power. The ideal feminist persona has morphed again: from queer Palestinian terrorist to trans anti-Zionist activist.

In the constitution of the National Women’s Studies Association, passed in 1982, the association declared—over the objections of Jewish women and contrary to the term’s definition—that it opposed antisemitism “as directed against both Arabs and Jews.” In 2015, the organization passed a BDS resolution. In 2017, Linda Sarsour, a Women’s March founder, announced that Zionists could not be feminists (and her co-chair, Tamika Mallory, later defended the notoriously antisemitic Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan). In 2017, Puar’s book The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability argued that Israel maims Palestinians on purpose, and was rewarded with a major NWSA book prize. In 2022, after most major Gender Studies departments signed the pledge in solidarity with Palestinians, Cary Nelson, author of 2019’s Israel Denial: Anti-Zionism, Anti-Semitism, and the Faculty Campaign Against the Jewish State, called it “a watershed moment” when “academic programs for the first time officially represented themselves as vehicles of anti-Zionism.”

Texts from the 1970s and 1980s still dominate feminist discourse—and inspire movements like Black Lives Matter—but Nice Jewish Girls and Yours in Struggle have been out of print for years. There is now a cottage industry of white-women-are-bad books, like 2021’s The Trouble with White Women: A Counterhistory of Feminism, in which Rutgers Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies professor Kyla Schuller writes that Betty Friedan (who, she points out, was born “Betty Goldstein”) “advocated a form of biopolitics”—that is, optimizing the lives of white women at the expense of poor women and women of color. The white woman—that pariah of feminism, who in her most archetypical form, looks, sounds, and quite obviously is Jewish—has become worse than the patriarchy. She is a Nazi. A eugenicist. And like Israel itself, in the works of these new feminist anti-Zionists, she wants women of color dead.

V. The Feminist-izing of Anti-Zionism

A version of this story ends back where it began: Women’s Studies, born of different strands of feminism, expelled women, thereby allowing the movement to return to its leftist roots. But feminism has also provided the Left with new tools to rationalize its anti-Zionist hatreds. A 1990 book called Jewish Women’s Call For Peace: A Handbook for Jewish Women on the Israeli/Palestinian Conflict suggests that Palestinian women are giving other women hope that they will “succeed in destroying the patriarchal system.”

In America, too, queer and/or black women are cast as resistors to the patriarchal United States, Israel, and male-dominated Jewish organizations. In Dean Spade’s 2015 documentary, Pinkwashing Exposed, a Jewish Voice for Peace activist employs the feminist vocabulary of rape to describe the Seattle city council allowing an Israeli LGBTQ+ group to give a presentation—a situation in which “unsuspecting, uninformed folks with really good intentions are brought into this against their will and consent.” Meanwhile, actual violence against gays and lesbians in Palestinian society—including abuse, ostracism, and murder—is blamed on Israel’s restrictions on mobility, which prevents Palestinian queers from organizing.

And feminism has given the Left the concept of intersectionality—a theoretical model designed to identify difference, but which now works to cover it up. It now strives to wage social justice struggles by analogizing to the point of false equivalence. This feminism, writes Angela Davis in Freedom, urges us “to think about things together that appear to be separate, and to disaggregate things that appear to naturally belong together.” White Western women who try to join women in the Global South fighting for reproductive rights or against rape and abuse are now imperialists guilty of assuming a false sameness. But Ferguson, Missouri, is Palestine. Says Davis, “I often like to talk about feminism not as something that adheres to bodies, not as something grounded in gendered bodies, but as an approach.”

This kind of feminism is not necessarily by, about, or even sympathetic to women. It favors what feminist postcolonial theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak calls “strategic essentialism,” or the tactical deployment of identity while maintaining suspicion about identity categories. It promotes the suppression of speech over dialogue with its support of BDS. It flourishes in Cultural Studies, American Studies, and other “Studies” fields with a myopic approach to intellectual topics. “No U.S. Aid for Genocide!” a Gender Studies professor I had once been on a panel with posted a week after the October 7th massacre. “Stand on the right side of history.” It is clear that feminists no longer understand history—certainly not the history of Israel or Jews or the Zionist feminists who spent years working for peace—nor do they care. Today’s feminist theory is art pretending to be history, brilliantly referencing and riffing on older feminisms, and offering blueprints for a new and supposedly better world—a world in which, as in many leftist iterations past, the destruction of Israel is a foregone conclusion.