Gaza

The Athens of Asia: A History of Gaza

For much of its history, Gaza moved people, things, and ideas by land and sea, and its name was associated with geographic interconnectedness.

Gaza City, the largest city in the Gaza Strip, is today one of the most isolated and unlivable cities in the world. But for over two thousand years, traders, sailors, shipbuilders, farmers, fishermen, architects, and scholars recognized great possibilities in the climate, soils, and strategic location of Gaza. Though it now relies on the World Food Program, Gaza’s name was once synonymous with the wine it produced, which was considered a delicacy in France, among other places. Today, Gaza is cut off from international trade, but it was one of the most interconnected commercial hubs on the Silk Road. Gaza has virtually no tourism. But it was once visited by such luminaries as Mohammed, the Roman emperor Hadrian, and Winston Churchill.

Gaza sits at the southeast corner of the Mediterranean Sea, on the edge of Asia, where it meets Africa. As a Silk Road entrepôt, Gaza received goods from thousands of kilometers east—including places like Uzbekistan and India—and shipped them to Mediterranean markets in Africa, Europe, and Asia.

At the time of Jesus, Gaza was the last stop on the still more ancient Incense Trade Route, over which gold, frankincense, and myrrh traveled, like the gifts the Three Wise Men are said to have brought to Bethlehem. Gazan merchants moved aromatics coming in from Yemen and Arabia to markets all around the Mediterranean. The city was fringed by farms, which brought olives, dates, and wine to its busy markets during its Egyptian, Greek, Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, Arab, and Ottoman eras. In fact, last year a Gazan farmer made headlines when, on digging to investigate why his olive trees were not taking root, he unearthed a large mosaic floor from the days of the Byzantine Empire.

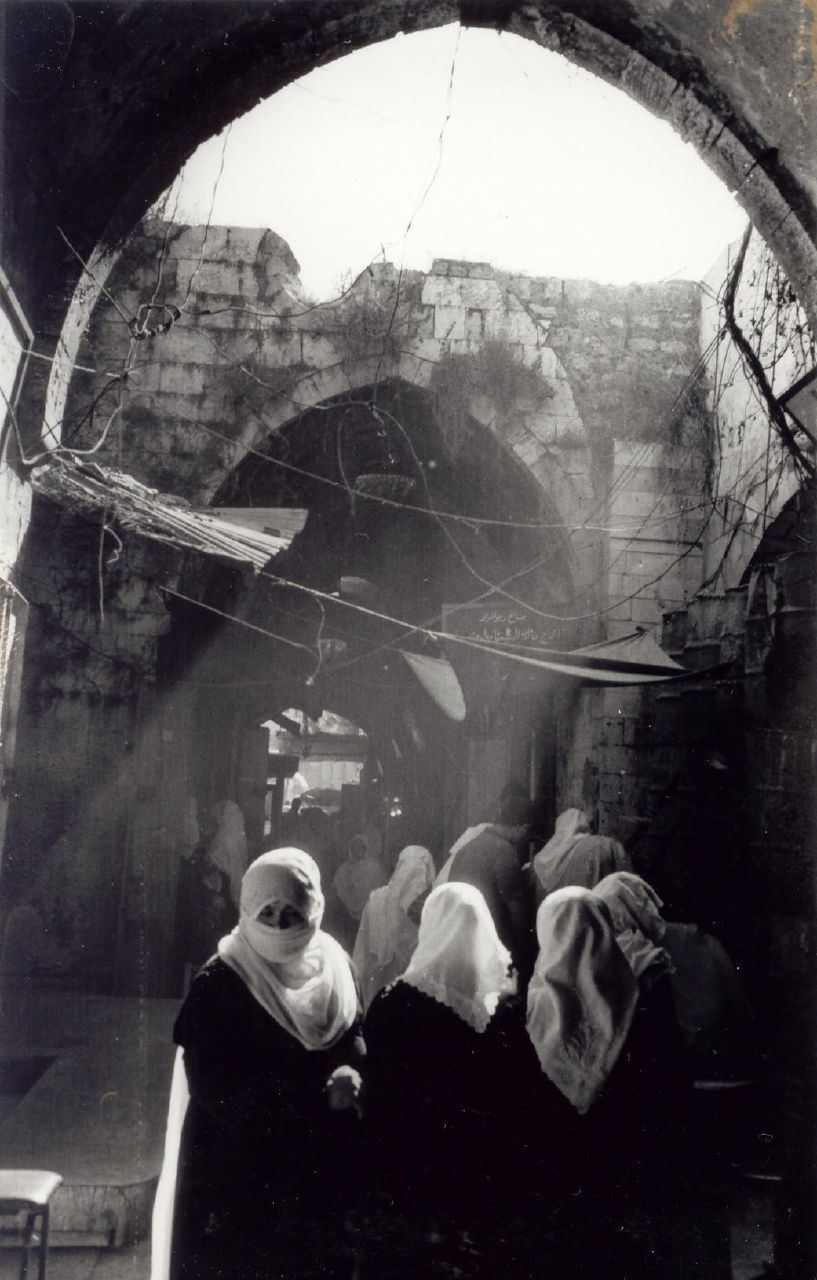

In Late Antiquity, Gaza was a Greek-speaking Byzantine center of philosophy and rhetoric, known for its openness to diverse ideas and cultures overlapping from three continents. The fifth-century Byzantine Christian philosopher Aeneas of Gaza called the city “the Athens of Asia.” As the Byzantine Empire lost its grip on the Eastern Mediterranean to Arab caliphates over the course of the 7th century, Gaza’s language changed from Greek to Arabic and its churches were replaced with mosques. But Jewish and Christian communities remained in Gaza—and continued their viniculture, which was banned by Islamic law. Under Arab rule, the port of Gaza became a key node on the Islamic sea trading network that controlled three-quarters of the Mediterranean coastline, from Syria to Spain.

But as the Arab empire began to fracture, Gaza fell into neglect. By the time Crusaders arrived in 1100, they found it uninhabited and in ruins, according to the historian William of Tyre. Crusaders rebuilt Gaza as an outpost for pilgrims and travelers headed to and from the Holy Land. In 1149, the city was placed under the protection of the Knights Templar, the Pope’s warrior-monks and financiers of the Crusades, and it became a fortress town guarding the Egyptian border of the medieval Crusader state called the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Gaza fell to Saladin in 1187 but was retaken by Richard the Lionheart in 1192.

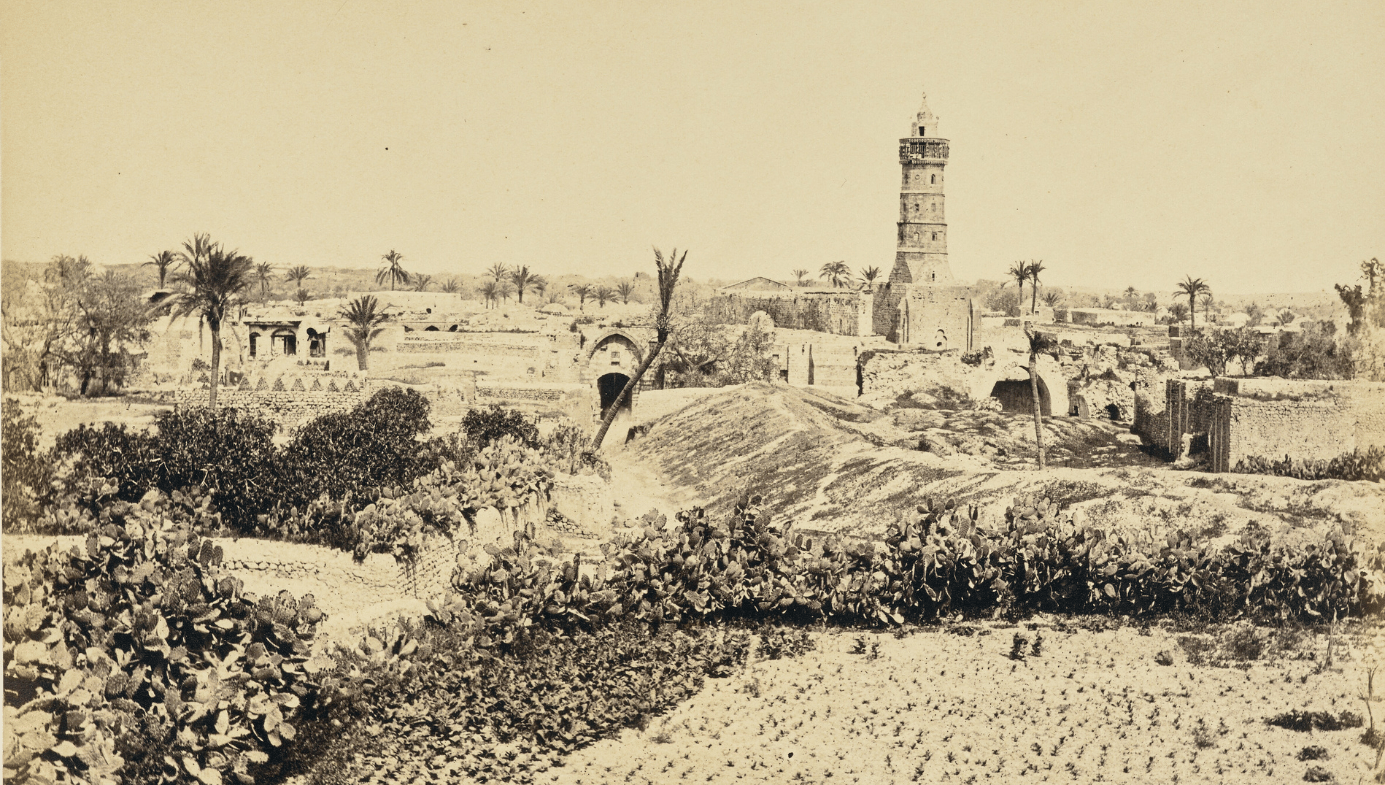

As the Crusades waned in the 1300s, Gaza was conquered by the Islamic Mamluks, and was once again transformed into a flourishing metropolis. Mamluk governor Sanjar Al Jawli oversaw a massive wave of construction projects, including a hospital, Islamic schools, open-air markets, public baths, and a horse racing course.

But in the 1400s, the European Age of Exploration opened new sea routes to the Far East, which reduced the need for Silk Road Muslim middlemen, like those of Gaza. By the time the Ottoman Empire cavalry rode in and took over in 1516, Gaza was a small town in decline again.

The Ottomans ruled Gaza for over 400 years. The first few centuries were peaceful and prosperous, and the prosperity extended to Jews. In his 1991 book The Jews of the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish Republic, historian Stanford J. Shaw relates that there were “150,000 Jews in the Ottoman Empire as a whole at its height in the sixteenth century, approximately three percent of its population, compared to only 75,000 Jews in Poland and Lithuania at the same time.” In other words, the world’s largest Jewish population was in the Ottoman Empire, which the historian Tahir Kamran claims “provided a principal place of refuge for Jews driven out of Western Europe by massacres and persecution.” When the Ottomans took over, about 1,000 Jewish families lived in what is now Israel, and Gaza was one of the principal cities Jews inhabited. In fact, Jews had lived in Gaza since Biblical times, and Gaza is mentioned in the Old Testament as one of the five city-states ruled by the Philistines. Traces of Gaza’s old Jewish Quarter can still be found today.

The later Ottoman Empire fell into decline and neglected many of its outlying territories, including Palestine and Egypt. This encouraged Western powers to move in, with their missionaries, scholars, and merchants. Gaza became an important grain depot, with a German steam mill, and it exported barley to England to make beer. In an attempt to sever Britain’s trade routes to its colonies in India, Napoleon led an expedition to conquer Egypt and Palestine. In 1799, he personally marched into Gaza at the head of 13,000 troops, calling it “the outpost of Africa, the door to Asia.” American Presbyterian minister and historian Edward Robinson, sometimes called the “father of Biblical geography,” traveled through the Holy Land in 1838 and reported that Gaza produced soap, cotton, apricots, mulberries, and olives, and that it was a key stop on caravan routes for Bedouin traders between Syria and Egypt. In short, for much of its history, Gaza moved people, things, and ideas by land and sea, and its name was associated with geographic interconnectedness.

This began to change around the turn of the 20th century, when life in Gaza became more about surviving disasters and conflicts than pursuing prosperity through its status as a hub of goods and ideas. Gaza is situated near a geological fault called the Dead Sea Rift. In 1903 and 1914, the fault caused earthquakes that destroyed parts of the city. During World War 1, most of Gaza’s urban housing was damaged or destroyed in the First, Second, and Third Battles of Gaza, and in 1917 the British captured the city from the Ottomans. In 1920, what was left of post-Ottoman Gaza became part of the British territory known as Mandatory Palestine, which existed from 1920 to 1948. Some 135 of Gaza’s Jews were killed by Arabs in anti-Jewish riots in 1929. This forced the Jews to leave the city, although some later returned. During the Mandate, Palestine’s Jewish population doubled as over 400,000 Jews immigrated, especially from Germany, Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Poland. But Gaza remained almost entirely Islamic: A 1945 survey shows that the district of Gaza had 150,540 residents (it was the fourth largest district in Mandatory Palestine), of whom 97 percent were Muslim, 2 percent Jewish, and 1 percent Christian.

Mandatory Palestine came to a violent end in 1948, after the United Nations agreed that the territory would be divided between a Jewish and an Arab state. The Arab state would comprise about 43 percent of Palestine’s area and 40 percent of its total population and would be 99 percent Arab and 1 percent Jewish. The Jewish state would cover 56 percent of Palestine’s total area and contain nearly half its population and would be 55 percent Jewish and 45 percent Arab. The Jewish side accepted this deal, but the Arabs rejected it, and thus the 1948 Israeli Declaration of Independence set off the Palestine War.

Jewish Zionist militias swept through Palestine and took 78 percent of the territory, far more than the 56 percent in the UN plan. By the time Israel and Egypt signed the 1949 Armistice Agreements that ended the war, some 6,000 Israeli Jews and over 10,000 Arabs had been killed in the fighting. Many of the 700,000 fugitive or expelled Muslim refugees crossed the Armistice Line from Israel into the Gaza Strip, which was then administered by Egypt. Meanwhile, in the three years that followed the war, around 600,000 Jews immigrated to Israel, including 260,000 from neighboring Arab states.

Israel took Gaza back from Egypt in the 1956 Suez Crisis, then returned it again—only to retake it once again (along with the West Bank and other territories) in the Six-Day War of 1967. Israel hoped to trade these captured Palestinian territories with its Arab neighbors in exchange for peace, but a deal never materialized.

Many other attempts at a two-state solution have been made, including the Oslo Accords in 1993, in which the Palestine Liberation Organization recognized Israel’s sovereignty. But Gaza’s chances of being part of a two-state solution evaporated with the election of Hamas in 2007, the last election ever to be held in Gaza. Hamas has never wavered from the purpose stated in its founding charter, the 1988 Hamas Covenant:

Israel will exist and will continue to exist until Islam will obliterate it, just as it obliterated others before it. … [Hamas] strives to raise the banner of Allah over every inch of Palestine. … The Prophet, Allah bless him and grant him salvation, has said:

“The Day of Judgement will not come about until Moslems fight the Jews (killing the Jews), when the Jew will hide behind stones and trees. The stones and trees will say O Moslems, O Abdulla, there is a Jew behind me, come and kill him.”

In 2005, Israel unilaterally disengaged from the Gaza Strip, removing its military and all 21 Israeli settlements. In 2017, Israel offered that if Hamas demilitarized, returned Israeli captives and MIAs, and recognized the State of Israel’s right to exist in peace, then Israel would invest heavily in turning Gaza’s refugee camps into the “Singapore of the Middle East,” including building a seaport and airport to make Gaza a high-tech international crossroads. Hamas refused, and today, according to the UN, the average Gazan lacks potable water and lives on two pieces of Arabic bread a day.

Privately, Israel has asked Egypt to allow Gazans to escape the humanitarian disaster of the Gaza Strip and move into refugee camps in Egypt’s Sinai region. But the prospect that a mass exodus of Gazans might bring Hamas onto their soil has made Egypt and other Islamic countries wholly uninterested in taking Gazan refugees. The political geography of Gaza has thus remained a lose-lose stalemate since 1967: its Muslims are stuck in an isolated corner of a Jewish state, while Israel is stuck with a hostile territory it has never really wanted to govern. Israel’s former prime minister Levin Eshkol called Gaza “a bone stuck in our throats.”

The bustling prosperity of Gaza’s past and the impoverished confinement of its present illustrate how differing societies can shape the same landscape in starkly contrasting ways. And they show how the same geographically-blessed site can be connected or isolated, recognized or overlooked, fought over or abandoned, developed or wasted.

The philosopher Aeneas of Gaza wrote that “soul’s nature is so great, just because it has no size, as to contain the whole of body in one and the same grasp; wherever body extends, there soul is.” Today, the body of Gaza is cramped between heavily-guarded border walls and a coastline off limits to maritime exports. But as a bridge between seas and continents, Gaza will always have geography on its side. Many waves of prosperity, cultures, and empires have come and gone. It is hard to imagine now, but there will be a time when the body extends again, and travelers bound for foreign shores will once more sail out over the waves of Gaza.

Editor's Note: It is believed that Muhammad visited Gaza. Sources differ on this.