People often ask me, “What would your parents think about you living as a Jew now?” After the October 7th massacre in Israel and the concomitant rise in antisemitism across the globe, I think they might say, “We told you so.”

My parents were Holocaust survivors, born and raised in Budapest. My father’s father and brother were murdered by Hungarian Nazis (Arrow Cross). My mother’s father was deported to Bergen Belsen and died when the Allies bombed a train the Nazis were using to transport prisoners. Her mother went missing a few days after my grandfather’s deportation and, according to one story, was beaten to death by antisemitic hooligans.

My mother and father, however, managed to avoid being deported or murdered, living out the last few months of the war alone in hiding. In the late forties, they escaped Hungary as it devolved into communism and met as refugees in Austria. They emigrated to Canada, got married, and had three boys. They both became doctors. And they both became Christians. The former was to ensure a good living. The latter was to protect themselves and their family from violence and hatred.

I used to think my parents were crazy when they explained why they converted. They said they feared antisemitism and they wanted to protect us from it. In 1970s’ White Plains, NY, where I grew up, antisemitism felt like long-ago, far-away history, like polio or hoof-and-mouth disease. It was not something a kid like me would ever have to worry about—certainly not in America. I believed that well into adulthood.

My father told me about his and my mother’s background sometime in my 13th year, a kind of Second-Generation bar mitzvah. And he swore me to secrecy just as he had my brothers when they were that age. He wasn’t supposed to have told us until we were grown up. That was the deal he had made with my mother. She wanted our non-Jewish identities to fully solidify first.

But at around the age of 13, my older brother started asking my parents why all our relatives were Jewish, and so they told him but swore him to keep the secret even from his two younger siblings. I believe my next oldest brother was also 13 when he was told. He’s not sure. But I remember my mother saying that sometime after the Yom Kippur War, my father experienced a burst of Jewish pride and told him (the dates would seem to line up). That brother also kept the secret from me until my father let me know, for no apparent reason other than that I was now also 13.

But though they eventually told us the truth, my parents weren’t so confident that they would allow us to reveal our secret to the world. That, my father told me, was not safe. Don’t tell anyone, he said, because they’ll hate you for being Jewish. So, what did I do? For most of my life, I lived as a Christian, alternately believing and agnostic, until I reached the age of 40. After a life-changing trip to Israel, I had myself circumcised and renamed at Mount Sinai Hospital in Chicago.

I married an Israeli-American. We had a child. We had him circumcised by a mohel in a synagogue on his eighth day of life. We gave him a Jewish name and now spend a third of my salary on his Jewish day school. Today, I wear a yarmulke most places I go, lay tefillin daily, and on Saturdays, I attend a synagogue where, even in the best of times, an armed guard stands at the entrance. Since October 7th, they’ve been patrolling the whole campus, inside and out. They wander past father-son prayer services with AR-15s in hand, dressed in khakis and Kevlar vests.

Maybe it wasn’t so bright, what I did. Maybe my parents weren’t so crazy.

I did once ask my mother what my father would have thought of my return to Judaism. He passed away before that happened. She told me an old Hungarian joke that went something like this:

Two friends were standing by a pond, and one said to the other, “What will you pay me if I eat a live frog?” The other said, “$100.” His friend figured he could use the money, so he reached into the pond, grabbed a frog, and choked it down. The other friend paid but felt bad for losing so much money. “How much will you pay me if I eat a live frog?” he asked. His friend said, “$100.” And so the man reached into the pond, grabbed a frog, choked it down, and got his $100 back. Then they looked at each other and asked, “For what did I eat a frog?”

What is the meaning of this parable? That in suppressing and hiding their Jewish identities, my mother and father were swallowing a frog in hopes of a great benefit, not money, but safety for their children and grandchildren. But now that I was openly living as a Jew (and my brothers were both “out” in their own way), it seemed like they had eaten the frog for nothing. My mother’s answer implied that my parents’ renunciation of their Jewish identities came at a cost. Child that I was and adult that I became, I had never considered that until then.

What was the cost? I can only speculate. It’s hard to estimate the price of living a lie for half your life—of hiding from friends, from colleagues, from your own children, an essential part of your identity. It wasn’t just that they were Holocaust survivors. That was only part of the life they hid. They hadn’t just survived the war. Before the war, and throughout their childhood, they had lived as Jews, albeit assimilated ones. Both had to keep hidden for most of their life the social and religious foundation of their identity.

My mother’s family was “Neologue,” the Hungarian version of Reform, and they were minimally observant but ran in pretty much exclusive Jewish circles. My mother won a Torah-study award as a teenager. Her father and his friends formed a minyan with a Torah scroll on High Holidays. My mother once told me that if it weren’t for the war, she almost certainly would have had a shidduch (being set up with an eligible Jewish man)—maybe not in the manner of Yenta, the meddlesome matchmaker in The Fiddler on the Roof, but through social connections and such.

My father was raised by a Zionist, socialist, atheist, and failed entrepreneur. The only Jewish education he got was during the summer or two he spent with his grandfather, who insisted he learn a little Hebrew. But all his relatives, everyone he knew growing up, were Jewish. As an adult, he had a good friend in Israel to whom he occasionally sent money and whom he even visited. And despite his irreligious upbringing, he seemed to have more trouble keeping the secret than my mother. He would sometimes drop hints, like when he mentioned “cholent”—a traditional Sabbath dish of beans and barley—to my first Jewish girlfriend, who didn’t yet know my background.

Being Jewish was an integral part of my parent’s identity that they amputated when they moved to America, and they almost certainly suffered phantom pain in that missing limb. It also contributed to a kind of social isolation. They cut themselves off from other Jews, the people they could most easily relate to. Certainly, they made friends with non-Jews, but it was harder than it might otherwise have been because they had to pretend to be something they were not.

So, yes, the frog did not go down so easily. Maybe that’s partly why my mother, having lived as a Lutheran for more than 50 years, also came out as Jewish in the end. After attending my wedding in Israel, celebrating Shabbat and Jewish holidays with my family, and seeing that it wasn’t just some phase I was going through, she too felt the pull of her old identity. And when the time came, she asked to be buried as a Jew and put that in my charge. And so she was, chevra Kadisha (Jewish burial society), pine box, kaddish and all. And thankfully, everything looked pretty good from a Jewish perspective in 2013 when she died.

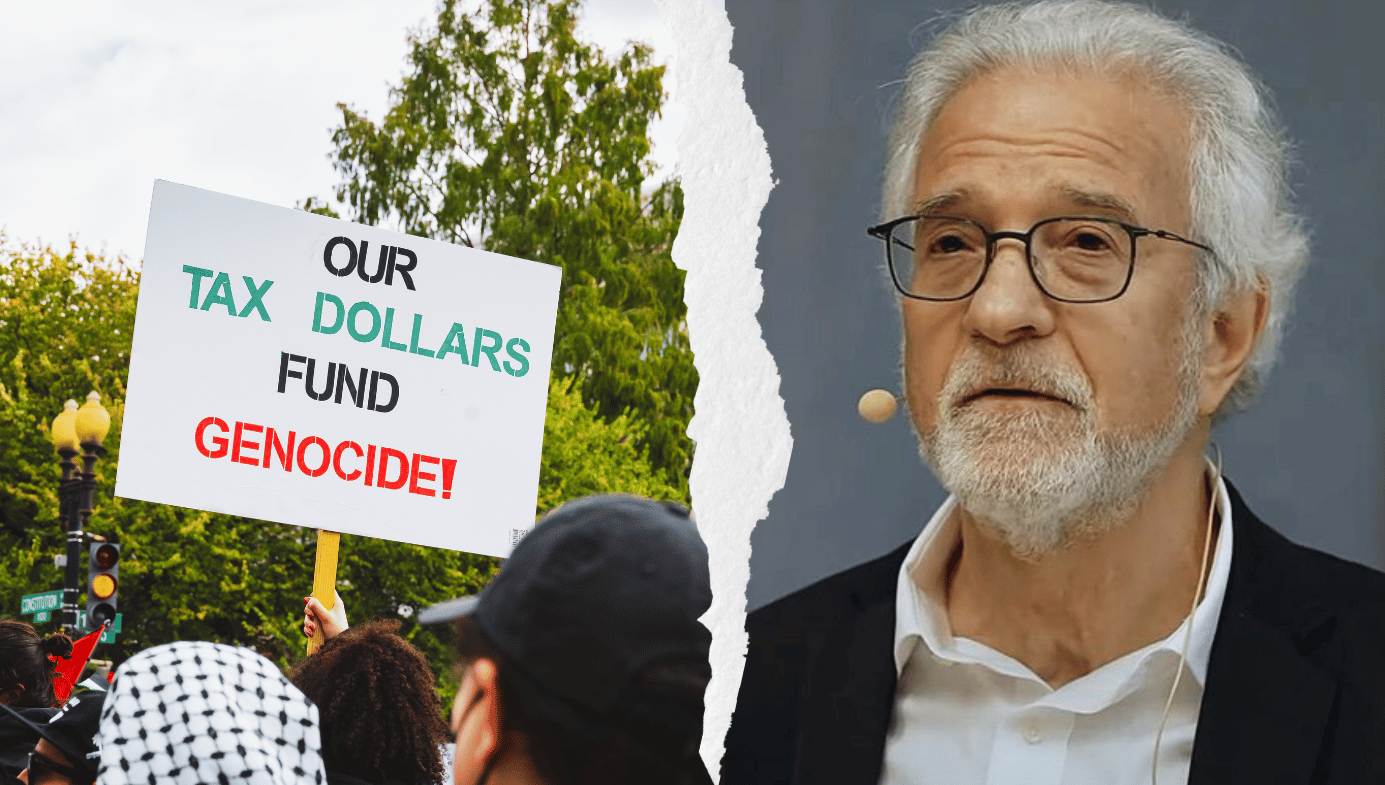

But now, with some 1,200 Israelis dead, women raped, infants killed, elderly taken hostage, with Western pundits and intellectuals explaining these atrocities were justified by Israeli policy, with Jewish students fearing for their safety at American universities, with the Jews in good ol’ White Plains, NY, telling their congressman that they feel unsafe “living as Jewish people in their own community,” I wonder what my parents would say.

I think I know what my mother would say. I once went to see The Merchant of Venice on Broadway with her. That was back around 1989, long before my return to Judaism. The show starred Dustin Hoffman as Shylock. He gave a great performance. I bought a poster with his and the rest of the cast’s autographs. I still have it somewhere.

Shakespeare’s play tells of how a Venice merchant named Antonio borrows money from a Jewish lender, Shylock. Smarting from years of insults from Antonio, Shylock lends the money on the “playful” condition that if Antonio can’t pay it back, he must surrender a pound of his flesh. When Antonio’s investments flounder, he defaults on the loan, and Shylock demands payment strictly according to the contract, refusing to accept even triple the payment in cash from friends of Antonio. When he is rebuked for seeking vengeance, Shylock responds with one of Shakespeare’s most famous monologues:

I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? Fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?

There is endless debate among readers and scholars as to whether the play is antisemitic or sympathetic to Jews. As Tevye the Dairyman might have said, on one hand, there is Shylock’s dramatic speech defending the humanity of Jews and attacking the hypocrisy of Christians. On the other hand, there is the depiction of Shylock as a vengeful villain. Shylock’s rage is understandable, but the play ends with Shylock losing his daughter to a Christian, having half his wealth confiscated, and being forced to convert to Christianity.

As we stepped out into Times Square, I asked my mother what she thought. She said the message was one she knew well: “The Jew always gets screwed in the end.” I want to say to her now that this is not true. I want her to be wrong. For the sake of the Jews; for the sake of Israel; for the sake of my family in Givatayim, Balfouria, and elsewhere in the Holy Land. For the sake of my son.

Whether it’s because I suffer from a severe case of second-generation pessimism or because I take what the enemies of Israel say at face value, it’s not hard for me to imagine an end to Israel, an end that would cost hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of Jewish lives. I’ve no doubt the country can defeat Hamas, but then there’s the threat of Hezbollah, whose fighting force is some three times that of Hamas, and who possess about 150,000 rockets, as well as drones and guided missiles that can reach any part of Israel. Even though Israel’s defense minister has promised to bomb Lebanon back to the stone age if they get too cheeky, it’s not hard to imagine Hezbollah pulling off their own, more deadly October 7th. And then there’s the Iranian regime, which has publicly called for Israel’s destruction and which is perilously close to getting a nuclear bomb. Israel has nuclear weapons already, of course, but is it so hard to imagine that mutually assured destruction might not deter Iran’s radical regime from pushing the button? Even a conventional war with Iran could be catastrophic for Israel. In the Iran-Iraq War, the two countries suffered hundreds of thousands of casualties over eight years. Both Iran and Iraq were able to limp away from that fight. With its much smaller population and geography, I’m not sure Israel, could. How much war, then, can Israel take before the Jewish nation-state becomes untenable? How many 10/7’s can it sustain?

But as I ponder the possibility of Israel’s destruction; as I witness the collaboration in the legacy media with the lies of Hamas; as I hear threats against Jews, not just in the Middle East, not just in Europe, but in America as well; as I remember Squirrel Hill; as I remember purchasing a handgun to defend my shul, I can see my mother’s point of view more clearly. Hers was a view informed by history and by own her own life experiences. And nearly any rational weighing out of the evidence would support her conclusion—that the Jews will get screwed in the end.

Of course, there’s the irrational evidence against this point of view—the spiritual arguments of faith and trust in God. There’s a famous saying among Jews: “They tried to kill us. We won. Let’s eat.” There’s a recent photo taken of my Israeli family standing in front of Auschwitz, a small nation of Jews descended from one survivor, my mother-in-law, who at age nine, was sent to the death camp.

Religious Judaism cites the miracles of the Exodus, the conquering of Canaan, the turnabout of Purim, the triumph of the Maccabees, the 1948 War of Independence, the Six-Day War, and the raid on Entebbe as evidence that, in the end, the Jews triumph. But for every Exodus from Egypt, there is an attack by Amalek. For every Chanukah triumph, there’s a Masada. For every Six-Day War, there’s a Yom Kippur War. For every Raid on Entebbe, there’s a Munich Massacre.

Will Israel defeat Hamas? Probably. But what will follow? What is Israel going to do with a subdued Gaza? As one writer has observed, no third party—not the Arabs, the US, not NATO, not the UN—is likely to step up and assume control of the Strip. Israel will be left holding the bag. Again. In which case, it will be back to the status quo: unending conflict with the Palestinians, the precarious position of Jews in what is supposed to be a safe haven, and worldwide hatred of Jews for being “colonial settlers” and the like.

Sometime after the Squirrel Hill shooting, I was interviewed for a local television channel. The reporter asked me how we could end antisemitism. I said we can’t. Only the coming of the Messiah could end it. I meant what I said, though I can’t say I believe that will ever happen. As a Jew, I’m supposed to believe in the Messiah. Maimonides says so. Some people I know believe he’s already come. Theoretically, I believe. But the rational part of me still hears the echo of my mother’s observation, “The Jew always gets screwed in the end.”

And yet, in the end, my mother asked to be buried as a Jew. Why was that? At the time, some of my family suggested it was because she was old, infirm, no longer in her right mind. She had experienced serious and disturbing bouts of delusion, including a fear of Germany’s reemergence as a superpower. (“Tell your rabbi not to worry,” she told me. “When the Germans come to his door, it will be okay. They’ll just want to teach his children German.”)

But she wasn’t always delusional in those last years, and mostly she was not. If I had thought it was only delusion, I would not have gone ahead as confidently as I did with the Jewish burial rites she requested. I believed there was some kind of change of heart. And if that was the case, it is possible that she also changed her mind about Jews getting screwed in the end. Maybe she saw my marriage and the birth of our child as a happy ending. It’s a faith I’m trying to hold onto myself, the same faith that kept the Jews going after the Holocaust, after the Romans destroyed the Second Temple, and after the Babylonians destroyed the first.

I once learned a story about the Druids called “Donar’s Oak.” I suspect it’s more myth than truth, but it went something like this. At the end of the eighth century, a Christian saint who wanted to convert the Druids cut down an oak tree in which they believed their Gods lived. When the Druids saw the tree die, their faith died with it. True or not, the story has lived with me since college as an instructive myth. Destroy a religion’s Holy of Holies, and that religion will die. But this has not been true of the Jews. Even if we always get screwed in the end, we somehow keep going. If Israel doesn’t survive, the Jews will. Or maybe just Judaism will.

In Bernard Malamud’s God’s Grace, a single Jew survives the apocalypse to find himself on an island full of talking apes whom he tries to civilize. He fails, and they kill him. But at the end of the novel, a lone gorilla finds his yarmulke, dons it, and says the Shemah, the most important Jewish prayer of all, asserting the unity of God and his lordship over Israel. The idea seems to be that you can kill the last Jew, but Judaism will never go away. But honestly, that’s not a lot of comfort to a guy who just wants his son to live a long, prosperous life, to build a family, to live free of fear. It’s little reward for swallowing the frog of antisemitic hatred and violence.

I do not come from a family of martyrs. My parents did everything they could to avoid being murdered for being Jewish, including denying their Judaism. For my parents, “Never again” meant “never again will we see our families die for that religion.” When my mother was marched to a train station to be deported with her father, she noticed some of the Jews casually walking away. She pointed this out to her father, and he said, “I’m not brave enough, but if you think you can, do it.” She did. She took off her Jewish star, got on a trolley car, went into hiding, and never saw her father again.

When my father was arrested with his father and brother and brought to the Arrow Cross headquarters, he told his captives he wasn’t Jewish. He said he was the maid’s son. He was friendly with a doctor there who backed up his story. And my father had hazel-blue eyes. So, they bought it and released him. He never saw his father or brother again.

My parents didn’t sacrifice themselves for Judaism. They sacrificed their Judaism for themselves and their offspring. And yet here I am, a religious Jew, worrying about the safety of my family in exactly the way my parents tried to prevent.

So, was I wrong? Was I a fool to choose the path I chose? When I think about potential rewrites of my own history, when I entertain the idea of retconning my past—What if my father had never told me and my brothers the truth? What if I had never gone to Israel and reconverted? What if I had stuck to my Christian upbringing? —I sometimes think of that great, wise Jew William Shatner, and his boldly going screen persona, Captain Kirk.

Near the end of Star Trek V, Kirk rails against the idea of second-guessing life choices, of questioning whether he should have turned left when he turned right. Pain and guilt, he says, cannot be taken away: “They're things we carry with us, the things that make us who we are. … If we lose them, we lose ourselves. I don't want my pain taken away. I need my pain.”

Yes, it’s fruitless to second guess one’s life course, and it is foolish to wish away pain, though we might sometimes wish it were less. I’ve received immeasurably good things from Judaism: a wife, a child, a people, a way of life, an answer to the question of what I am doing here on Earth and what I should do, a lens through which I can see a world full of meaning instead of devoid of purpose, a discipline, a faith, a path to hope, a call to trust.

Is it worth it? The risk, the feeling sometimes that, as a Jew, there’s a proverbial, if not an actual, gun to my head. I think so. From the relative safety of my home in America, anyway. I don’t know how I would feel if I were in Israel right now. I know I was there in 2014 when rockets were being fired at the country from Gaza, and I didn’t much like it. But in the end, we’re all going to die.

It’s not that, like in that old Pretenders’ lyric, “I wanna die for something.” It’s that I want to live for something. And Judaism has given me more reasons to live than anything else I’ve found, more than the Christian faith I was fostered in, more than the Brit Lit idols who inspired me in college, more than the epicureanism that got me through my thirties.

They say, “It’s not easy being a Jew.” But, for me, it wasn’t easy not being one. In the end, I couldn’t keep down the frog of assimilation that my parents had swallowed on my behalf. But I now understand that their decision to swallow it was a rational and intelligent act. And I’m grateful they made the effort, even if, in the end, I rejected the gift they gave me: the chance to live as a non-Jew.