Politics

Gaza, Islam, and the West

The Hamas atrocities of October 7th have refocussed attention on the place of a consequential voting bloc in Western democracies.

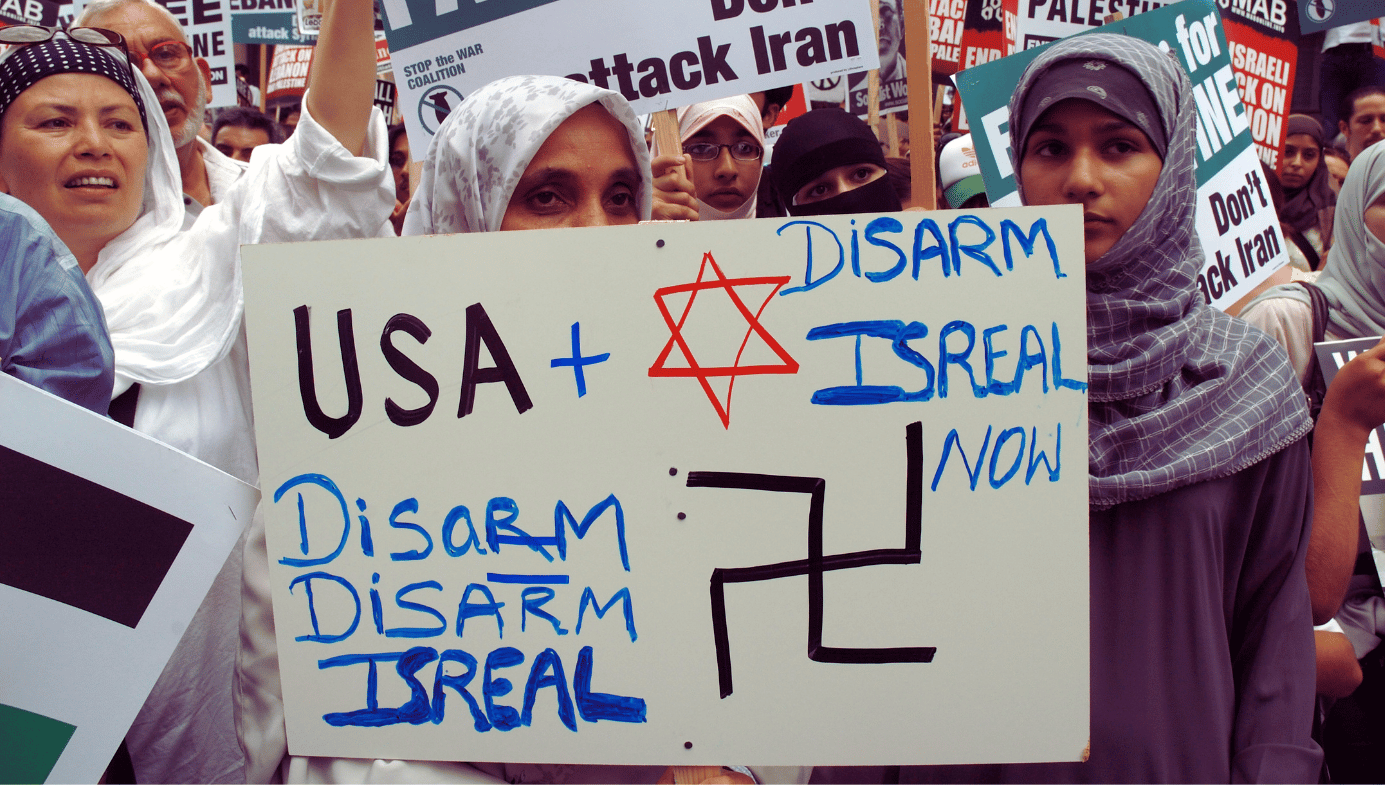

The Hamas attacks on Israeli civilians committed on October 7th have refocussed attention on the place of Muslims and Jews in the Western world. A number of activists on college campuses and elsewhere have downplayed if not dismissed the attacks, which included rape, torture, mutilation, and the indiscriminate massacre of around 260 defenceless people at a music festival. The day after the atrocities, the New York City chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America held a rally in support of the Palestinian cause. In Sydney, Australia, pro-Palestinian supporters chanted “Gas the Jews” in front of the city’s iconic Opera House.

The question of the place of Islam in Western culture is particularly acute in France—home to the largest Muslim and Jewish populations in Europe. In 2016, Pew Research estimated that 8.8 percent of the French population was Muslim, and that this could grow to as much as 18 percent by 2050. Since most elections are won by smaller margins than this, Muslims may—if they form an organised voting bloc—play an influential if not decisive role in French elections in the future. Who is likely to profit from this? And how might Islam manifest itself politically?

There are two principal possibilities. The first is that Muslims form an alliance with the progressive Left, a scenario imagined in Michel Houellebecq’s 2015 novel Submission. In that book, Mohammed Ben Abbes, leader of the Muslim Fraternity, beats Marine Le Pen in the presidential election in an alliance with the Socialist party and implements Sharia. The novel ends with François, a Sorbonne professor, settling in to a surprisingly comfortable life of submission to the regime.

The second possibility is that Muslims join hands with other people of faith as Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, later Pope Benedict XVI, posited in his 2006 book Christianity and the Crisis of Cultures. Ratzinger argued that, as people of faith with moral laws derived from the Ten Commandments, Muslims have more in common with Christians and Jews than they do with atheist progressives.

Writing when the text of the European Constitution was being considered, Ratzinger objected to the omission of any reference to Europe’s Christian roots in the document’s preamble. Ratzinger’s concern was not that Europe might become Islamised but that it might become more secularised. The European Constitution was rejected by voters in France and the Netherlands. The Treaty of Lisbon, which contained substantially the same provisions, was nevertheless ratified without a democratic mandate following a “period of reflection.”

Needless to say, there was no reference to Europe’s Christian roots in the Treaty. Christianity’s status in Europe today is the same as all other faiths, a belief structure one is entitled to practise as long as it does not interfere with other people’s freedoms in the process. Europe is not a Christian continent but a continent in which everything, including religion, is subordinate to the absolute value of freedom.

This should concern Muslims as much as Christians, according to Ratzinger, who wrote:

[Muslims] do not feel threatened by our Christian moral foundations, but by the cynicism of a secularized culture that denies its own foundations. … It is not the mention of God that offends those who belong to other religions, but rather the attempt to build the human community absolutely without God.

This is not to say that Ratzinger felt an Islamo-Christian alliance would be an easy one. Christianity is based on the Word, the logos. Since its beginning, it has understood itself as a religion of reason in which there is a spiritual and temporal life. In the Divine Comedy, written in the early 14th century, Virgil, who represents human reason, guides Dante out of hell. The Qur’an, on the other hand, descended on Mohammed. It leaves room neither for interpretation nor harmonisation with nonreligious values. According to Ratzinger:

[Islam] does not have the separation of the political and religious sphere which Christianity has had from the beginning. The Koran is a total religious law, which regulates the whole of political and social life and insists that the whole order of life be Islamic. Sharia shapes society from beginning to end. In this sense, it can exploit such partial freedoms as our constitution gives[.]

There are, however, points the two faiths share. During the Second Vatican Council, the Catholic Church published a declaration acknowledging that Christians and Muslims worship the same God, that Muslims recognise Jesus was a prophet, and that both faiths “value the moral life and worship God especially through prayer, almsgiving and fasting.”

The notion of a pan-religious alliance is therefore plausible in principle, and at times has appeared plausible in practice. Just a few months ago, Muslims and Christians protested a teacher’s insistence that their children participate in LGBTQ “pride” events in Alberta, Canada. A similar event occurred in October of 2022 when Muslims and Christians protested the presence of books with LGBTQ themes in the school curriculum in Michigan, USA.

But a seismic shift has occurred in our culture since Ratzinger’s remarks. In 2005, freedom was the absolute value, but by 2015 it had shifted to the defence of the weak. Statistics appear to support this view. According to Time magazine:

From 2011 to 2014, polling by Gallup found that millennial Democrats sided with Israelis over Palestinians by 25 points when asked their views on the long-running conflict. By 2023, the same group sided with Palestinians over Israelis by 11 points—a 36-point shift.

Curiously, this inversion of the Nietzschean obsession with strength has led to the same place as the 20th century political movements Nietzsche’s philosophy inspired: false accusations against Jews and an indifference—if not grisly satisfaction—in their suffering and destruction. In Weimar Germany, Jews were said to undermine national strength; today they are criticised for defending their own homeland too strongly. Jews must shout louder or whisper more quietly, according to the exigencies of the moment. Palestinians meanwhile must be defended at all costs, regardless of their own role in the violence now directed towards them.

We are in the bizarre position where atheist progressives who support the advancement of gay, female, and minority interests also support those who would like to set these causes at naught. In France this phenomenon is called Islamo-gauchisme (Islamo-leftism), a term coined by French philosopher Pierre-André Taguieff, who noticed the tendency of leftwing intellectuals and politicians to support the Palestinians during the Second Intifada in the early 2000s.

Last month, Jean-Luc Mélonchon, the leader of the far-Left party France Insoumise (France Unbowed)—which placed third in last year’s presidential election and now leads a powerful leftwing coalition—refused to denounce Hamas. People, he tweeted, should not be forced “to align themselves with the position of the extreme right-wing Israeli government.”

The dividing lines are now clear. The Palestinians have the Left’s unqualified support whatever they do or say. The Jewish diaspora must hope the centre can keep the rising tide of antisemitism at bay. Some will say Islam is not an amorphous ideology. This is true. But, as Brett Hall has argued in these pages: “Mainstream Islam explicitly teaches its adherents that Jews deserve death simply for being Jews.”

The process of leftist alignment with Islamic ideology has been underway for some time. In 2006, Judith Butler said: “Yes, understanding Hamas, Hezbollah as social movements that are progressive, that are on the Left, that are part of a global Left, is extremely important.” Butler recently condemned—in a highly qualified manner—the Hamas attacks on Israeli civilians. But this backpedalling is unconvincing since violence against Jewish civilians is explicitly endorsed in the Hamas covenant:

The Prophet, Allah bless him and grant him salvation, has said: “The Day of Judgement will not come about until Moslems fight the Jews (killing the Jews), when the Jew will hide behind stones and trees. The stones and trees will say O Moslems, O Abdulla, there is a Jew behind me, come and kill him. Only the Gharkad tree, (evidently a certain kind of tree) would not do that because it is one of the trees of the Jews.”

Logically, Islam should not fit with any major Western political ideology. Homophobia and female subjugation make Islamic beliefs incompatible with the post-Christian, victim-fixated Left. Antisemitism and its totalising nature render it incompatible with (disproportionately Catholic) European conservatives.

The only real question is: which group is cynical enough to exploit a voting bloc whose views it finds, at least in part, abhorrent? For the time being the answer is unquestionably the Left. In Submission, the narrator’s Jewish girlfriend, Myriam, is forced to flee France for Israel in the face of government-backed antisemitism. Given the unholy alliance we are now witnessing, the scenario presented in the novel may not be as far-fetched as it once seemed.