Editorial

Let Israel’s Critics Have Their Say

No one should suffer professional or academic repercussions simply because they voice support for Palestinian rights and welfare.

On October 24, the directors of eLife—a not-for-profit, peer-reviewed scientific journal covering the biomedical and life sciences—announced that they had fired their Editor-in-Chief, University of California computational biologist Michael Eisen. In a public statement, the directors noted delicately that Eisen’s use of social media had “at key times been detrimental to the cohesion of the community we are trying to build and hence to eLife’s mission.”

This was a not-so-veiled reference to a one-word tweet—“bingo”—that Eisen had appended on October 13 to a satirical article from The Onion, titled, Dying Gazans Criticized For Not Using Last Words To Condemn Hamas.

Bingo https://t.co/yapO3iVY0d

— Michael Eisen (@mbeisen) October 13, 2023

In case it isn’t obvious, the dark joke at play here targets pro-Israel activists and journalists whose relentless focus on Palestinian political extremism allegedly serves to obscure the scale of Gazans’ wartime suffering. Eisen’s tweet came less than a week after Hamas’ terrorist attacks, and emotions were still raw. Some of the comments under Eisen’s tweet included “dying 10-[month old] baby did not speak before being shot dead with her father in Kibbutz Be’eri. A real baby whom I knew, very close. Shame on you,” and “You know they would kill you” (a presumed reference to Eisen’s Jewish identity).

This kind of dark humor isn’t universally appreciated at the best of times. And this being just days after the most horrific slaughter of Jews since the Holocaust, it was very, very far from the best of times. Making matters worse, Eisen then proceeded to argue with his Twitter critics. That usually ends badly. Doubly so in this case, since nothing is more likely to suck the redeeming humour out of a controversial joke than an extended analysis of its social value.

Eisen kept his composure and argued in good faith. He also reminded his critics of his Jewish identity and Israeli family connections. But it didn’t matter because this is the sort of argument one loses merely by having it. Yaniv Erlich, an American-Israeli scientist and Columbia University professor, told Eisen (who had, by this point, also been expressing horror at the “collective punishment already being meted out on Gazans”): “Empty words. For seven days you haven’t tweeted [any] words of supports for Israeli researchers, some of [whom] lost kids and friends. And now you dare to give us military advice from your privileged position of safety. What a moral bankruptcy.”

Empty words. For 7 days you haven't tweeted a single time words of supports for Israeli researchers, some of which lost kids and friends. And now you dare to give us military advice from your privileged position of safety. What a moral bankruptcy.

— Yaniv Erlich 💔 (@erlichya) October 14, 2023

In regard to the substance of their disagreement, we’re inclined to take Erlich’s side. But as opponents of cancel culture, it’s Eisen’s fate that primarily concerns us. Yes, it was unwise for a prominent journal editor to tweet out that particular kind of joke at that particular time. And yes, this wasn’t exactly Eisen’s first offence: In 2018, for unexplained reasons, he tweeted out “Fuck Israel.” (His journal’s board members reportedly had words with him back then, but let him stay on as editor.) At the end of the day, however, Eisen was fired for sharing a joke. On that basis, the term “cancellation” is apt.

Of course, conservative cancel culture is nothing new. In Texas, a public school teacher was recently fired because she’d assigned an illustrated adaptation of Anne Frank’s diary to her eighth graders. And two other teachers from the same state were fired, they claim, for attending a drag show. But stories such as these tend to originate in deeply conservative jurisdictions. In recent weeks, by contrast, we’ve witnessed a broader phenomenon: Even within their native progressive milieus, such as left-wing political parties and university campuses, strident critics of Israel have been censured, denounced, and, yes, sometimes even cancelled.

Context is important here, however, because every case is different. At McGill University in Canada, to take one useful example, the Provost sent a mass email to the university community on October 10, condemning—by name—a campus group known as Solidarity for Palestinian Human Rights (SPHR). The school also ordered the group to stop using the university’s name in its public communications. Days later, a group of professors, staff, and librarians organized a petition, which denounced the administration for compromising SPHR’s “academic freedom,” including the members’ “right to express their views on political matters in the classroom [and] various public arenas on and off campus.” When phrased in those principled terms, that very much sounds like a free-speech campaign worth supporting.

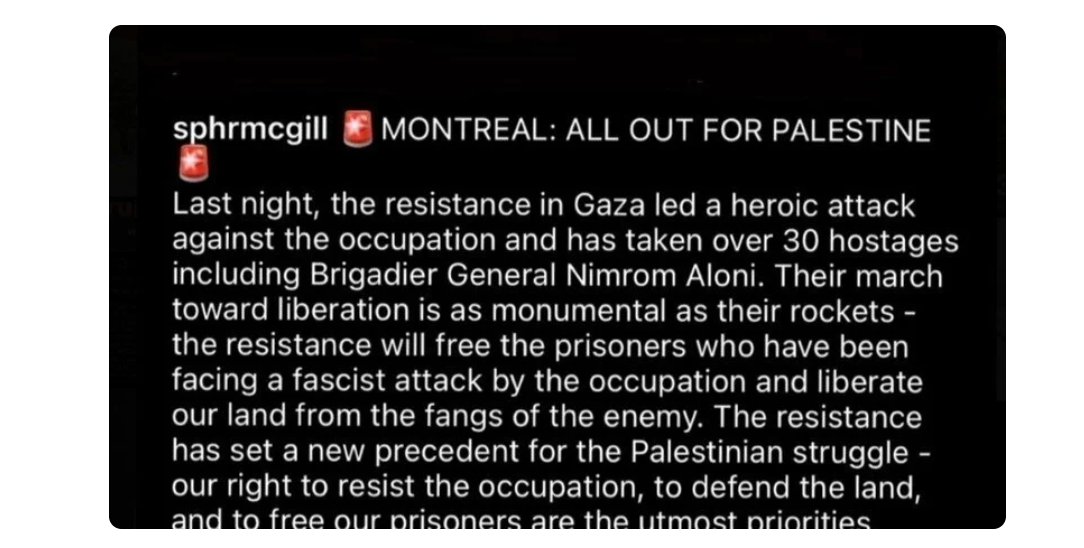

Until, that is, one investigates the actual content that SPHR was broadcasting on its social-media channels—which did not just comprise support for a ceasefire in Gaza, or a call for more humanitarian assistance. Rather, SPHR explicitly celebrated the October 7 Hamas terrorist massacre—which it called “a heroic attack.” (In an absurd and incoherent attempt to explain away that since-deleted post, SPHR subsequently claimed it had been misunderstood, explaining that “we are not celebrating violence. [Rather], we are looking at the prospect of liberation.”)

Here at Quillette, we generally do our best to support free speech, broadly defined. But if a group of students publicly rhapsodizes over the “heroic” slaughter, rape, and kidnapping of innocent civilians, we really have no problem with school administrators denouncing their bloodthirsty rhetoric. And if the group and its leaders become infamous on campus as a result, they have no one to blame but themselves.

As we’ve seen with more “traditional” manifestations of cancel culture, the real danger to free speech comes when categories are intentionally blurred by cynical actors who seek to censor the expression of entire viewpoints—such as when opposition to, say, affirmative action or police defunding is denounced in the same breath as crude racist slurs. And as the case of Michael Eisen shows, there is a real possibility that this kind of rhetorical tactic will be used to stifle debate over Israel’s response to the October 7 terrorist attacks.

Certainly, no one should suffer professional or academic repercussions for voicing their support for Palestinian human rights, criticizing Israeli military tactics, advancing explanations of the current crisis that emphasize Israeli historical crimes (real or otherwise), or otherwise endorsing pro-Palestinian narratives—including through peaceful street protests, impassioned rhetoric, and, yes, satire.

In the shadow of the Hamas attacks, these statements often will evoke bitter disagreement from those who take a view that is more closely rooted in sympathy for the victims of Hamas terrorism. But conservatives, no less than progressives, must make their peace with ideological pluralism. If they don’t, they’ll have no basis for complaint when—as is usually the case—the shoe is back on the other foot.