race

British and Black

Contemporary antiracism imposes an American framework that distorts our understanding of racial issues in different countries.

A Review of This Is Not America: Why Black Lives in Britain Matter by Tomiwa Owolade, 336 pages, Atlantic (September 2023).

When the novelist Zadie Smith accepted the Langston Hughes medal in 2017, she recounted that when she first came to the US, African Americans called her “sister,” despite the fact that she hails from the British Isles. “I had entered a broader consciousness in which national borders had little meaning. I was part of a historical and geographic diaspora that has penetrated every corner of this globe, and which no single passport can contain or express,” she explained. The diaspora in question comprises 350 million human beings, dispersed across the planet as a result of New World slavery, colonialism, and migration. As a result, being black encompasses an enormous diversity of experiences and histories.

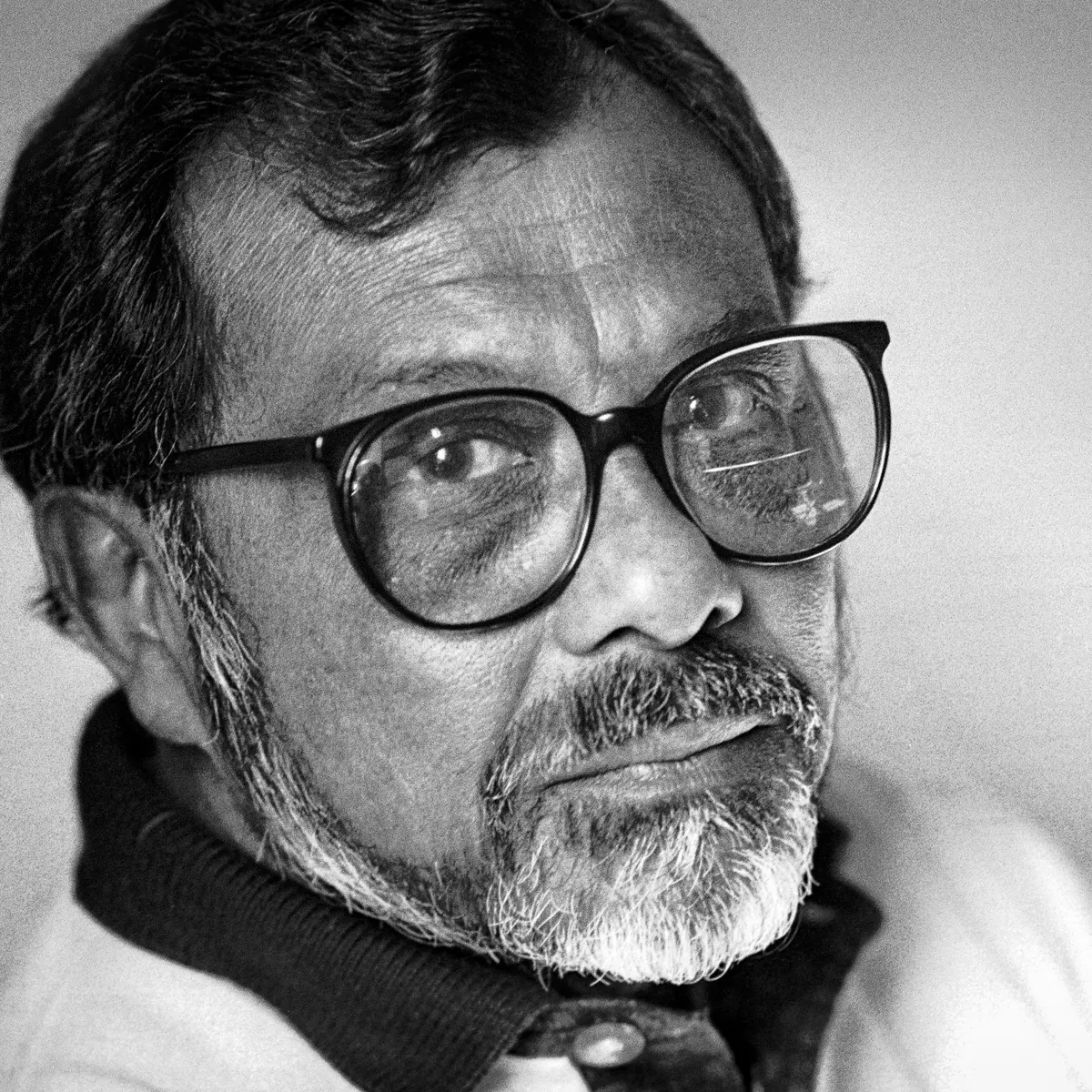

Tomiwa Owolade’s new book is an interesting elaboration on this point, with a particular focus on the specificity of black life in Britain. He is particularly disgruntled with contemporary antiracist politics in the UK, which he feels inappropriately imposes an American framework that distorts our understanding of racial issues in this very different country.

Owolade was first struck by how perverse this Americentric approach can be when students at his alma mater, University College London, used the acronym BIPOC (“black, indigenous, and people of colour”) in an open letter demanding more “diversity” in education. As Owolade points out, “something strange” is at work there. The notion of indigenous people as a marginalised group makes sense in America, a country settled by colonialists who extirpated many Native American tribes as they expanded across the continent. But in Britain, only fascists use that word, as part of their anti-immigrant propaganda.

In the last few years, the anxiety that Britain’s racial politics is becoming more Americanised has become widespread. Commentator Alex Hochuli has argued that the supposed “awokening” of 2020, during which Black Lives Matter protests erupted internationally in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, represented the “global triumph of American idealism.” While it is noble for non-Americans to express solidarity with American causes, Hochuli points out that many go well beyond this. They imagine themselves as participants in American struggles, “eagerly adopting the slogans and paraphernalia of a uniquely American protest” in a way that obscures their own specific problems, especially with regard to race.

As Owolade points out, “race doesn’t define British society the same way it defines American society.” He isn’t denying that Britain has its own long, deep history of racism or that race doesn’t still structure British society. It does—but in a very different way from the way it does in the American context because different countries have different histories, and thus will develop different understandings of race.

It would be wrong—even arrogant—to assume that America is the only country in the Western world with a seemingly intractable race problem. One need only remember this June’s riots in France over the police killing of the 17-year-old French Algerian Nazel Merzouk. The point is not that America has a monopoly on racism—it’s that a society must be understood on its own terms before we can ever truly grapple with its racism.

There are multiple differences between the black populations of Britain and America. For one thing, America has a far more racially diverse population: 60% of America is white; 80% of Britain is. Black Americans comprise 13% of America’s population; Black Brits are only 4% of ours. Most black Britons came to the UK from former colonies in two waves of post-war migration: first from the Caribbean and later from a range of African countries. As a result, black Britain is highly ethnically heterogenous, and most black Brits are first- and second-generation immigrants. Most black Americans, on the other hand, are the descendants of slaves trafficked into the New World from Africa and can trace their presence in America all the way back to the seventeenth century—longer than many white Americans.

As a “mixed race” person myself (specifically, a “mulatto,” to use an arcane term), I am struck by the differences in the way in which I am perceived in the two countries. “Mixed race” is more likely to be seen as its own category in Britain, distinct from black, while in America, because of the legacy of the one drop rule and a strong African American communal identity, it’s more likely to be regarded as synonymous with black.

There are other differences, too. We have very few police shootings of black men because most police officers in Britain are unarmed and police shootings of all kinds are rare. Police brutality in Britain more often takes the covert form of “deaths in custody.”

Moreover, there were no slave plantations in Britain itself—the slave plantations that financed the British Empire were located in the colonies—nor were there ever any equivalents of Jim Crow or redlining. There were, however, many unofficial attempts to enforce segregation in social venues, such as “No blacks” signs at pubs, until the 1968 Race Relations Act outlawed them. As a result, the history of slavery can feel more distant and impersonal for black Brits than it does for their Americans counterparts. This history also means that we don’t have the all-black ghettos—which often seem like worlds unto themselves—that exist in many American cities. Even though some housing estates and neighbourhoods have a significance black presence, black Britons still always live cheek-by-jowl with other ethnic groups.

Tales about the horrors of the Middle Passage or lectures on the history of struggles against slavery will, by necessity, not have the same resonance for people who migrated or fled to Britain from Nigeria, Somalia, and Zimbabwe as they do for African Americans and Afro-Caribbeans. Both Owolade and I have Nigerian ancestry. We have our own distinctive relationship with the British Empire and with the colonial enterprise that brought our parents here. We should not ignore these different historical trajectories. The ubiquity of the American cultural model has led too many people to rely upon a generic notion of “blackness,” derived from a fantasy version of African American culture that’s been exported to the rest of the world, leading them to believe in a uniform “black experience.” This is a kind of American intellectual imperialism.

Another notable difference between the US and the UK—which, surprisingly, Owolade doesn’t mention—is evident when we look at the history of “political blackness” in Britain. In America, blackness functions as both an ethnic and a political identity for African Americans specifically. In Britain, on the other hand, for a long time being “black” denoted a political identity that embraced people of African descent and South Asians alike. “Black is the colour of our politics, not the colour of our skins,” as Ambalavaner Sivanandan once put it. This uniquely British phenomenon arose in the 1970s. It repurposed the American concept of black power, expanding it to encompass all racial minorities. In a society that regarded all non-whites as “coloureds” and treated Britain as a “white space,” it made sense for Afro-Caribbeans and Asians to use “political blackness” as a mode of resistance against racism. But times have changed. Demographic shifts in the UK, together with the ascendancy of identity politics, which is focused on more specific categorisations, have rendered political blackness defunct.

Among the imported Americanisms that Owolade highlights is what he calls the belief in the “disparity fallacy,” whereby any racial disparity—from a pay gap to a difference in the rates at which pupils are excluded (expelled) from secondary schools is axiomatically assumed to be evidence of institutional racism. Owolade invokes the black American economist Thomas Sowell’s point that it is foolish to assume that all the problems faced by black people are the result of racism. A single-minded focus on race can occlude other factors such as class, geography, and economics. The obsession with disparities between whites and ethnic minorities can also lead us to neglect important achievement gaps within these categories. For instance, as Owolade points out, black Africans generally attain better educational results than black Caribbeans and poor whites. One interesting counterintuitive disparity is that white Britons have a lower life expectancy than black Britons. Clearly, this isn’t because of racism against white Britons, but due to other factors unrelated to race.

As in America, there is a stark disparity in homicide rates between whites and blacks in Britain. Indeed, most Western countries have equivalent disparities in murder rates among historically oppressed groups. The indigenous populations of Canada, Australia, and New Zealand are more likely to be both perpetrators and victims of murder than the majority populations, as is Israel’s Arab minority. In Britain, blacks—especially young black men—are five times more likely to be victims of murder than whites. This has been the case for a long time. There was a 64% decline in the black homicide rate between 2006 and 2013, however, which reduced the disparity. This suggests that the problem may not be intractable, though it’s worsened again over the past few years.

People in their twenties—like Owolade and me—grew up in a multicultural society. It is hard for us to appreciate how intensely racist British society was not that long before we were born. Until recently, it was common for black Britons to encounter hostility. Police brutalised black men with impunity. Salman Rushdie described the force as “that colonising army, those regiments of occupation and control.” “Nigger-hunting” was a favourite sport of fascist thugs. Immigration policies were racially discriminatory by design. Interracial relationships were strongly taboo and severely stigmatised. Many blacks born and bred in Britain felt profoundly alienated from society. They didn’t know whether they really belonged because they often received the message that they were permanent aliens, whose “blackness” was a contradiction of their Britishness.

Thankfully, British society has progressed a lot since then. Social attitudes to race have become more liberal and inclusive. Judging by the latest surveys and studies, serious opposition to interracial relationships is negligible, the mixed-race population is booming, and most people don’t think being English has anything to do with having a particular skin pigment. And, like America, Britain has become a magnet for mass immigration: around a sixth of the population of England and Wales were born abroad.

There is evidence that Britain is far more racially integrated now, even as its population has become more multi-ethnic. In cities like London, Birmingham, Manchester, and Leicester, more people from different racial and ethnic backgrounds are living side by side than ever before. According to social geographer Gemma Catney, this is “something that’s happened really naturally over time without major government interventions.” London and New York are both world cities with very diverse populations of similar sizes; yet the former is far more integrated than the latter. Trevor Phillips was only partially right when he wrote that Britain is “the only country where a significant mixed-race population has come about through romance rather than rape,” since this is also true of France, Canada, and contemporary America. However, the prevalence of mixed-race Britons is a firm instance of what Paul Gilroy describes as “conviviality”: a civilised indifference to racial diversity, in which cosmopolitanism is neither aspirational nor exotic, but simply a mundane condition of everyday social life.

For a debut book by a fledgling writer, This Is Not America has had an impressive reception, receiving high praise from established commentators across the mainstream of the political spectrum: garnering glowing endorsements from such writers as Ian Baruma, Kenan Malik, Janen Ganesh, Tom Holland, and David Goodhart. The book has racked up positive reviews from centre-left, liberal, and right-wing outlets including The Guardian (in two separate reviews), The Telegraph, The Financial Times, The New Statesman, The Times (and The Sunday Times), Literary Review, and The Critic.

But of course, any polemic that grapples with race will have its detractors. If the right people are annoyed, that is as much an indication that you’re doing something right as if your book attracts widespread acclaim. One such person is black nationalist Kehinde Andrews, an epigone of Malcolm X, who lambasts “Uncle Tomiwa” whose arguments, he thunders, “exist solely to titillate racist White audiences.” Andrews takes particular umbrage at Owolade’s supposed “misreading” of James Baldwin and Ralph Ellison, whom he musters in support of his “integrationist worldview” (the “racist” idea that black Britons are fully British). This completely misses the point. The core idea in both Baldwin’s and Ellison’s critiques is that racism is a betrayal of America’s founding ideals. Unlike Andrews, they didn’t reject their country; they simply wanted to bring it more in line with its central premise.

If Owolade is the racial optimist, then Andrews is the racial pessimist who doesn’t think it’s possible or even desirable for whites and blacks to share the same society. As Owolade has pointed out, this is “woke Powellism”—the mirror image of white nationalist Enoch Powell’s views. Like Powell, after all, Andrews believes that it would be the “biggest mistake” for black Britons to “try to integrate into British society.”

This is Not America has a few flaws. Ironically, given that he has written a book-length polemic against taking an American perspective on British race relations, Owolade commits the same fallacy that he critiques. The American writer James Baldwin is mentioned multiple times, while British thinkers like Paul Gilroy and Stuart Hall, who would be vital in elucidating the dynamics of race and racism in the UK context, are mentioned only sporadically. Maybe these thinkers are too radical for Owolade’s taste, but a more serious engagement with them—even if it were for the purpose of disagreeing with them—would have greatly strengthened his argument.

It is also a shame that he omits to chart the history of political blackness in Britain. Owolade views himself as unqualified to address questions affecting British (South) Asians because he is “interested principally in black people in Britain.” But if he had looked at the issues that unite blacks and Asians, it would have helped him to understand how “blackness” has been demarcated by British society. There was a moment in our history when many Asians defined themselves as “black.” Even a brief exploration of this phenomenon would have shown just how porous, flexible, and contingent these racial categories are.

“Britain is the best country to be black!” boldly declared Kemi Badenoch, Britain’s Business Secretary, in a recent Conservative Party conference speech. According to Badenoch, in this country we see “people not labels.” This is the sort of statement that many people would view as nationalist triumphalism—especially coming from a Tory. It seems like a claim that racism barely exists in Britain. To me, this is hubris. But although Owolade would express himself with more humility, I think he would broadly agree with Badenoch’s pronouncement.

Many people would agree with him. According to a British Future poll from June of this year, most ethnic minorities agreed that though Britain has made progress towards racial equality over the past few decades, much more needs to be done. A majority of the black and Asian Britons surveyed said that they endure discrimination in the course of their everyday lives. However, 80% of them agreed with the statement that “the UK is a better place to live, as someone from an ethnic minority, than other countries like the USA, Germany or France.”

Owolade’s most potent argument is that to create a healthy civil society you must get past racial thinking. Racial categories are artificial: they do not refer to some essential truth about humans. But rejecting the concept of race doesn’t mean denying that racism exists. Racism exists and it matters. It is a blight on the human condition. Despite Badenoch’s confident assertion, we are still a society that labels people. We need to stop doing so. People shouldn’t be pigeonholed into narrow ethnic or racial categories. Such categories belie our individuality and our shared humanity. In Britain, America, and everywhere else in the world, it’s high time we threw the idea of race into the ideological rubbish bin of outmoded ideas.

In This Is Not America, Owolade exhibits a patriotic sensibility about what he elsewhere calls Britain’s “ancient, yet adaptable traditions and institutions.” His book concludes on a sanguine note that many may find provocative. He avers that the sceptred isle, despite its problems, is a far more “integrated society” than many imagine. He relates the story of Martha, a white secondary school student whom he was tutoring in English literature, who started to speak to him in a South London voice with “unmistakably African intonations.” Despite being white, Owolade writes, Martha “had a bit of black in her voice; but she was still, like me, irreducibly British.” Historian David Starkey once argued that the sight of whites turning culturally black was a sign of our degenerate times. For Owolade, it is a sign of interracial solidarity. For Owolade, black Brits are British first and black second.