Science / Tech

Clearing Out My Father’s Office

Reflections on a vibrant scientific career cut short.

I.

As far back as I can remember, my father worked at the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in Washington Heights, where he was a professor of microbiology and immunology. During the nearly 60 years of his professional career at Columbia, he had his laboratory, successively, in one of the three buildings occupying different corners of the same intersection at Fort Washington Avenue and 168th Street. So his career there divides roughly into three parts: his Neurological Institute years, his Black Building years, and his Hammer Health Sciences years.

This gave his presence there a sense of stability and durability—his laboratory perched high above northern Manhattan in the imposing medical center complex—that led me to feel, on an unconscious level, that he would be there forever. Occasionally, coming home as a child or, later, on visits home, I would see him crossing the busy intersection on his way to lunch or a lecture. In his white lab coat, walking at his brisk pace, oblivious to the traffic, he projected an aura of single-mindedness and determination. Moving among the buildings and his colleagues, he was totally in his element.

Through an improbable chain of contingencies, he had started out washing glassware at the medical center in the early 1930s, after graduating from City College at the age of 18 at the height of the Depression. At the same time, he embarked on the doctoral program in microbiology, obtaining his Ph.D. in 1937. Except for a couple of years at Cornell in the late 1930s and early ’40s, he had been there ever since. Starting in the mid-1970s, he divided his week between Columbia and the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, where he was an expert consultant to the Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and he maintained this schedule for the remainder of his career.

When my father began to show early signs of Alzheimer’s disease in 1993, it took a concerted effort by his immediate family to pry him loose from his ingrained routine. My basic impulse was to allow him to remain active as long as possible, since his work was synonymous with his life. But the first clear-cut symptom of the disease was a confusion about geography and how he was to get from Columbia, in northern Manhattan, to Bethesda. I heard about this from a member of my father’s regular luncheon group, who called to alert me to my father’s strange ideas about a commute he had been making on a weekly basis for two decades.

Before the phone call, I had been aware that my father’s short-term memory was deteriorating and that he often forgot what he had just told you a minute ago. When we were walking on Broadway together, he would stop and go through his wallet for minutes at a time, looking for something that he himself couldn’t remember, until I coaxed him to put his wallet away. Since he insisted he could travel anywhere he wanted, even abroad, we began to worry that sooner or later he would get lost or hurt. But he resisted his family’s pleas for him to reduce his demanding schedule and move gradually toward tying up the loose threads of his institutional relationships. This went against his basic make-up—against what appeared to be a biological urge to continue his work, no matter what.

He was living alone in his apartment, next door to the medical center, and trying to carry on. He was running his lab and writing grant proposals to continue his unbroken record of funding, maintaining that he could travel down to Bethesda, and expressing an interest in a conference in Seattle. On multiple occasions, when there was no answer at his apartment, it would turn out that he had gone to Bethesda or up to Cape Cod, where my mother had moved the year before. After a couple of days in Woods Hole, he would get fed up and come back to New York.

During this time, he told me that he had received an invitation to join a group of scientists visiting Central Asia and expressed a buoyant interest in going. I said something about it being a long trip entailing physically difficult conditions for someone his age. He said that he was interested in the work of Borodin. I asked who Borodin was, assuming he was some Russian scientist. But my father said, “Don’t you know Alexander Borodin, who composed In the Steppes of Central Asia?” This surprised me since my father had never shown much of an interest in music. I assumed it must be a memory from his youth that, owing to the tectonic activity occurring in his brain, was thrust up into consciousness.

This situation persisted for over two years. One evening, in the fall of 1995, I spoke to my father by phone, and he told me, first, that he had fallen on the floor while trying to sit down on a chair on wheels, and then that he had gone to sleep and left the apartment door unlocked. He also acknowledged that he was “shaky” on his feet, and concluded, “I guess I’m becoming a real basket-case.” This was the first time he had been able to acknowledge his condition.

Finally, after much deliberation, my older brother and I went down to Bethesda to empty our parents’ apartment on the NIH campus. And within a few more months, my father moved up to Cape Cod to be with my mother. It was clear that, in spite of his determination (which made me think of a beached sea turtle struggling to return to the ocean), he would not be coming back to his office. His lab had been empty for over a year.

After communicating with the head of the department, the moment arrived when it was time for me, as the son in closest proximity to his laboratory, to look through the effects from his office at Columbia in order to salvage anything of sentimental value before the department emptied out the space so that it could be passed to a junior researcher.

II.

Toward the end of a warm September day in 1997, I went to the Hammer Health Sciences Building to find the office on a lower floor. It was here that the university had moved my father’s belongings when he was forced to give up his laboratory space and office on the 12th floor, with its commanding view of the Hudson River and the George Washington Bridge. I was uneasy about what I would find and how I would manage, in an hour or two, to sift through the sheer mass of his accumulated papers and assorted objects for the few items that my brothers or I might want to hold on to.

I stopped at the office of the young faculty member next door—a rising star, I gathered—who was going to take over the space. He was very nice, and I liked him immediately. (This surprised me, as I did not feel particularly well-disposed toward representatives of this fresh young generation, whose rise was linked to my father’s decline.) He asked how my father was and commented that when Alzheimer’s patients are content, things are much easier. I realized he was trying to be understanding and to put a positive gloss on my father’s situation, but unfortunately, my father was not content. Quite the opposite, in fact—he was angry that his life was being taken from him.

The young researcher looked at the contents of the office with me. The floor-to-ceiling shelves along one wall had been neatly filled with books, monographs, and notebooks by Pabing, the devoted Philippino technician who had worked with my father for over 35 years. But the floor and counter in front of the windows were covered with stacks of reprints, papers, boxes, and antiquated computer equipment.

There were a few objects on the desk or shelves that caught my eye. One was a molecular model, which looked like it was made out of a long length of solder folded back on itself many times, with different segments painted in bright colors. The young researcher said, “That might be worth taking, if one knew what it was.” I seconded his assessment. But I was certain that it must be a model of an antibody combining site, since the major problem my father strove to illuminate was how the body can manufacture a vast number of highly specific proteins (antibodies) in response to foreign bacteria, viruses, or cancer cells (antigens).

I spent the next hour looking in drawers and cabinets, going through stacks of papers and reprints, and eyeing the books on the shelves to select the few things that I could manage to cart off. There were old datebooks, receipts, correspondence, programs and posters from scientific meetings, certificates in their cardboard tubes. It seemed there is nothing, no matter how trivial, that my father did not keep. And, because all of these artifacts testified to his former dynamism, they were tinged with a transcendent quality. At the same time, I was aware that my father never gave any thought to who would have to contend with the mountain of accumulated material. Of course, no one compelled me to undertake this task. I could simply have given the department permission to throw everything out. But true to my own nature, I seemed to be incapable of side-stepping these burdens.

By the time my father’s symptoms became apparent, a number of the colleagues and friends he’d had for over 50 years had made changes in their lives as they reached their 70s. They gave up their labs, took up other intellectual pursuits, refurbished their summer houses to spend more time by the shore, or made other changes. Unlike these people, whose professional and social lives paralleled his, to all appearances, my father never made any plan for slowing down, shifting gears, and bringing the long active phase of his career to a close.

I remember talking with him as winter approached and trying to persuade him to move up to Cape Cod to be with my mother, rather than living alone in Washington Heights so that he could continue to go to his lab, where, it was apparent, he was doing little more than passing the time. I pleaded with him, saying that he shouldn’t be living alone, that he needed help and looking after. He retorted that he detested Cape Cod and would be bored there, that he wanted to stay with his work. He didn’t care if he got hurt. I said, “So, you’re saying you want to die with your boots on?” and he nodded.

Unlike his colleagues, toward whom I could tell that he felt a degree of superiority, he seemed to believe deep down, viscerally, that the laws of aging that applied to others didn’t apply to him. His iron will had enabled him to overcome other obstacles, and he wasn’t about to change at this point in his life. He seemed to have an unconscious fantasy that either he wouldn’t die or that the world would end with him. So this man, who was such a planner in other realms of his life, never planned for a time when he would have to stop. This was ingrained in his personality and predated the dementia. But once the disease started to affect his thinking, it took away the very thing that he was trying to persist in doing—his work.

It came as a tremendous shock to him that the world continued to turn without him. It must be said that, for all his membership in prestigious societies and contacts with the luminaries in his field, virtually no one worried about how he was doing now that he could no longer do the work that meant everything to him. In the main, it was only his Chinese postdocs and his technicians, or in one case, a Chinese collaborator in Chicago, who bothered to telephone or visit him.

More from the author.

III.

Sifting through the piles of paper gave me ample time to think about my father’s life. The only son of Eastern European Jews, who came to this country in the 1880s, he never failed to be tickled by how far he had ascended from his origins. His children grew up with mythic stories of how his dressmaker father would drum up business by sending his wife around to department stores to ask for a particular type of dress that he just happened to have produced in excess. He would tell us how, during the Depression, when few people could pay the rent, his family had to abandon one apartment after another on the Upper West Side, sneaking out through the service entrance to avoid being seen.

On walks, he would point to the windows of a building across the street on Broadway, saying, “You see there, that’s where my stamp album got left behind.” He told us how he had worked as an usher in the Loew’s movie theater on Broadway and 107th Street while he was in college to help support his parents and sister. How he would walk the five miles uptown to the medical center in order to save the five-cent subway fare. How, right after graduating from City College in 1932 at the age of 18, he got that first job in the Department of Medicine at Columbia, washing glassware for Michael Heidelberger, who is known as “the father of quantitative immunochemistry.”

That position came about through my grandmother, who was friendly with Michael’s wife, Nina, to whom she sold dresses. When she asked about job possibilities for her precocious son, Mrs. Heidelberger suggested that he speak to her husband. As a condition for taking the job, my father asked that he be permitted to take on as much laboratory work as he was capable of. In retrospect, this first lowly job was an unbelievable stroke of luck that enabled him to support his parents and his younger sister during the Depression, and was also the first step in his long and phenomenally productive career. He worked during the day and took courses in the afternoon, evening, and during the summer session, and ended up getting his Ph.D. with Michael. They maintained a lifelong friendship, until Michael died at the age of 103.

After receiving his doctorate, my father spent a postdoctoral year in Uppsala, Sweden, where he demonstrated that antibodies were present in the gamma globulin fraction of blood, a discovery that made it possible to purify the protective antibodies in subsequent studies. Several years later, he developed a diagnostic test for multiple sclerosis as well as an animal model for this autoimmune disease. Those studies opened the way to the modern study of autoimmunity. In the 1950s, he went on to conduct studies of blood group substances and determined the chemical basis of the ABO blood groups. His decades of work on antigen-antibody interactions culminated in an analysis of the sequences of a large number of immunoglobulin molecules, which identified the “hypervariable region” of the molecule that determined the specificity of binding to a given antigen.

His work was recognized by prestigious awards, including the National Medal of Science, and numerous honorary degrees. The National Medal of Science citation read: “Kabat’s work has advanced our understanding of developmental biology, inflammation, autoimmunity and blood transfusion medicine, leading to treatments that have saved countless lives.” Colleagues referred to him as a “wunderkind” and as “a scientist’s scientist,” and many felt that he and Michael should have won the Nobel Prize.

In the laboratory, he was a notoriously tough taskmaster, insisting on the highest standards in conducting and documenting every step in an experiment. This rigor was inculcated in his students and technicians, who were terrified of coming in for his scorching criticism. They dubbed the trial by fire as being “Kabatized.” When it came time for one of his students to apply for a job, this training proved to be an invaluable asset, and my father wouldn’t let a student of his accept a position that was unworthy of him or her. His students became leading lights in the field of immunology, and one of them, Baruj Benacerraf, became a Nobel laureate.

In his professional relations, my father took a childlike pride in his reputation for being a straight-shooter, who could be blunt in his criticism of a colleague’s work and displayed low tolerance for bureaucratic obstacles. He seemed to feel that he could get away with undiplomatic behavior because his sole focus was on the work. One of the people I spoke with when making arrangements to clear out his office was an older secretary with an Irish accent, who said to me, “We loved your father, but he drove us absolutely nuts.”

When I was little, one of his postdoctoral students, who on one occasion failed to live up to my father’s expectations and came in for a bawling out (“I gave him the business” was a favorite expression of my father’s), had the presence of mind—and the chutzpah—to give my father a little pad about one inch wide and four inches long that had printed at the top in minuscule lettering the words: “Scratchpad for narrow-minded bastards.” No one appreciated the appositeness of this assessment more than my father, who was convulsed with delight.

My parents would host regular dinner parties for everyone working in the lab—lively and warm occasions, at which my father, a born raconteur, regaled his guests with tales of bureaucratic battles and eccentric researchers who overturned established dogma. His young guests from all over the world enjoyed my parents’ hospitality and my mother’s cooking.

IV.

As I was getting ready to leave the office, the young scientist came in. I asked him what his field is, and he told me that he works on how cells signal to one another. He asked me about 60 years’ worth of my father’s sera and other samples that were still taking up a cold-room on the 12th floor. There must be thousands of samples stored there, the earliest dating from the 1930s and ’40s.

My father used to routinely inject himself with a given antigen and then take his blood to study the antibodies produced in response. In other words, he used his body as a factory for the production of compounds of immunological interest. In an interview, he is quoted as saying, with his penchant for superlatives, “I’m probably the most intensively studied human with respect to antibody formation to a variety of things.” Whether the lymphoma that he developed late in his life had anything to do with this history of antigenic stimulation is an open question. He also archived samples of compounds of immunologic interest from patients with various cancers, multiple sclerosis, and other diseases.

Now, the department was planning to empty this cold-room of an archive assembled over so many years that, as I pointed out, probably has enormous value for researchers, if the samples were clearly labelled and documented. The problem, the young scientist remarked, is that there is no place to store so many samples. “I am willing to keep a box or a shelf of samples, if someone will select those that are of greatest value, but no one is going to keep thousands of samples.” I promised to speak to my father’s young Chinese collaborator, who had assumed responsibility for the samples.

Before I left, the young scientist pointed to a heavy, 1940s vintage, four-foot-high metal safe with a combination lock standing near the door. The department has been trying for months to find the combination to the safe but without success, he told me. My father no longer remembers it. The safe contains research materials, including samples of the notorious plant toxin ricin, derived from the castor bean, which my father had worked on during World War II, with a view to developing methods for detecting it and protecting against its toxic effects, since it had potential as a biological warfare agent.

My father’s laboratory characterized the molecule immunochemically and developed an antiserum for ricin poisoning. Ricin made headlines in 1978, when an agent of the Bulgarian secret police used the tip of a specially modified umbrella to inject a small amount of it into the calf of an outspoken Bulgarian dissident, who was standing at a bus stop on a bridge over the Thames. The dissident died almost instantly, and sophisticated toxicological tests were required to determine the cause of death. “Are you sure you don’t want this safe?” the young scientist asked me. “Your father told me that it has enough ricin in it to wipe out the entire planet.”

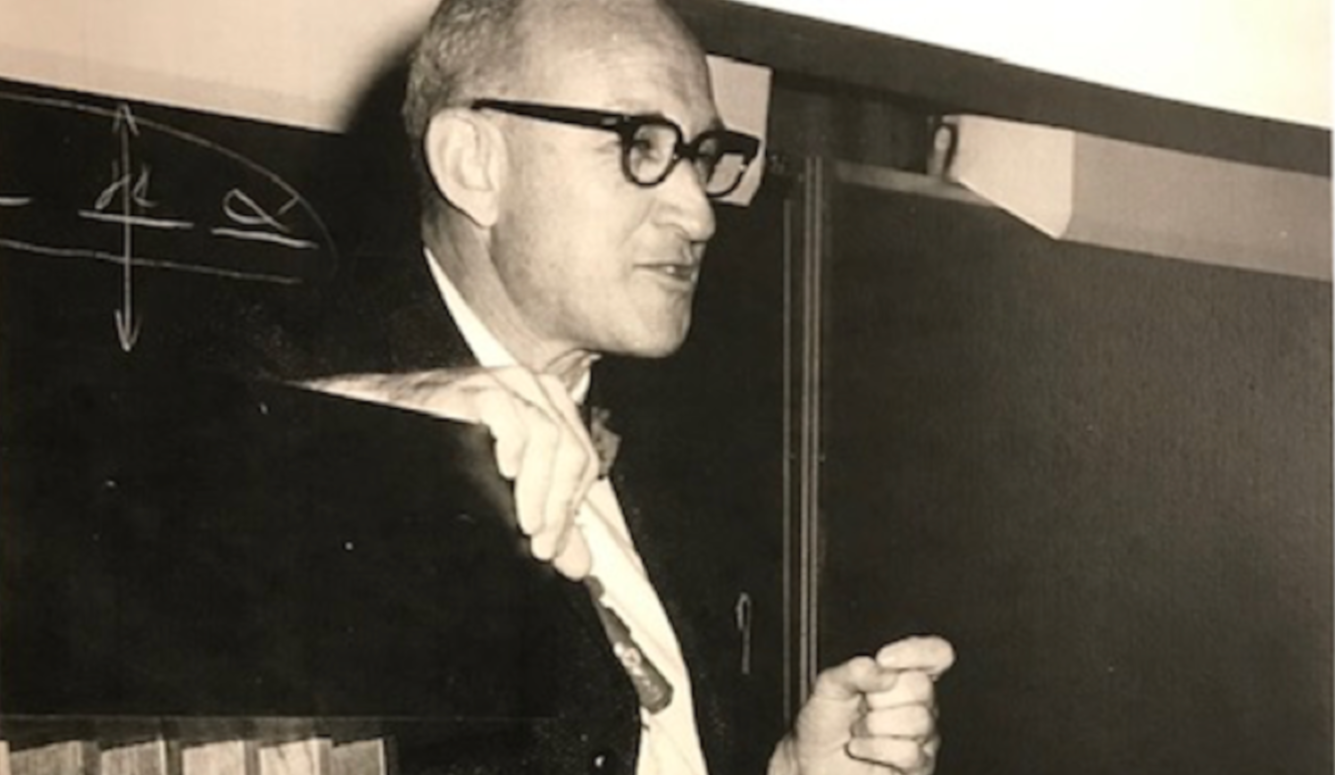

I ended up leaving with the molecular model, reprints of an autobiographical essay published a decade earlier, a couple of books, his name and address stamp, which he used on every book and reprint that came into the lab, and his photo ID badge. The ID photo, taken recently, seemed to betray a new frailness and a hint of confusion.

I had the nagging sense that I was probably overlooking many things that were worth keeping and that I would want to preserve. Now that my father could no longer look after himself and represent himself, I seemed to be assuming the role of his advocate and biographer. Someone had to ensure that valuable materials relating to his life were not thrown out, that they were either kept by the family or sent to archives that had an interest in them. But I was also aware that there was a deeper reluctance to allow the last remnants of my father’s 60 years of activity, the last physical signs of his presence here, to be cleared out and thrown away—a resistance to the knowledge that his long and vibrant career was finally over.