Politics

China’s Manufactured Fukushima Panic

The CCP has not missed an opportunity to inflame fears about its Japanese neighbor.

Back in the 1970s, “China Syndrome” was the fanciful scenario in which a meltdown at a nuclear power plant would lead to the reactor’s core components burning through the floor of the building and then all the way through the planet until they reached the other side, which, for some reason, was always imagined to be China. This sequence of events is impossible for a variety of reasons, but the term “China Syndrome” came to be applied to the notion that a molten reactor core could burn some way into the soil and water table beneath the power station, thereby contaminating crops and drinking water.

In 2011, the nuclear reactor meltdown at Fukushima sparked fears that Japan may experience its own version of China Syndrome. But although soils in the surrounding area had to be decontaminated in the aftermath of the disaster, the nightmare scenarios imagined by many did not come to pass. Twelve years on, however, Fukushima’s problematic nuclear legacy has finally reached China, albeit not in the way expected. We are seeing the vivid manifestation of an old malady among the people; a psychological condition long cultivated by the Chinese authorities.

With the deepening of the nation’s economic woes, Beijing is adopting a proven technique—redirect the frustration; encourage people to hate foreigners so much that they forget about their own domestic misery. And one particular set of foreigners provides them with the easiest of targets. For decades, the CCP-controlled education system has carefully nurtured a very specific hatred for the Japanese (hatred based largely on crimes committed by soldiers of the Imperial Army in Nanking in 1937).

An anti-Japan campaign was one of the tactics used by General Secretary Jiang Zemin to divert public rage after the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989. This task must have seemed close to impossible: how could the government ever make the people forget what it had just done to them? But many people did forget. They found that they were too helpless, the Communist Party too powerful, and Japan too easy to hate. The government’s playbook has not changed in the years since. As a result, a demonic loathing remains in many citizens today, just waiting for the Party to speak the right incantations and call it to the surface.

Typically, it is individual Chinese who end up suffering most. In 2017, a young Buddhist named Wu Aping walked into her local temple and placed memorial tablets for some of the Japanese soldiers who had participated in the Nanking Massacre. It was a quiet, personal gesture of reconciliation, and also a slightly idiosyncratic attempt to assuage her own recurring nightmares about the event. Photos of the tablets went viral, Chinese social media flared up, and the CCP responded. The temple’s abbot was sacked, the monks were sacked, the local officials were punished, and Wu herself was charged with the Party’s notorious, meaningless, all-encompassing crime “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” (which can carry a ten-year prison sentence).

Over the years, attitudes to Japan moved in unison with China’s general sociopolitical decline, and by 2022, just wearing a Japanese kimono had become dangerous. One unfortunate woman learned this when she posed for photos on a busy Suzhou street, wearing traditional dress in imitation of her favourite manga character. It wasn’t long before she found herself surrounded by police officers. “You are wearing a kimono, as a Chinese!” they shouted, as if in disbelief. The charge, once again, was “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.”

In fact, anything that looks remotely like a kimono is probably a bad idea in modern China, given that (a) the Party is said to be considering a ban on all clothing that “hurts the nation’s feelings,” and (b) communists don’t have the sharpest eyes. Several Wuhan residents were barred from entering a public park earlier this month when security guards mistook their Tang dynasty (ninth-century Chinese) dress for Japanese attire.

For the past month, government-orchestrated outrage has focused mostly on the release of wastewater from the nuclear power plant at Fukushima. Ever since the 2011 disaster, the plant’s ruined reactors have required gallons of water to prevent them from overheating. Once contaminated, the water is stored in tanks at the site. With 343 million gallons in 1,000 tanks, capacity has become severely strained. So, beginning in August of this year, Tokyo Electric Power began a 30-year process of pumping the water out into the Pacific.

While most radioactive isotopes have been successfully removed, there is no known process for filtering tritium from water. So the tritium remains. Japanese authorities are confident these tritium levels remain far below safety limits; the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) agrees. Indeed, there is little difference with the discharges from ordinary nuclear power plants. About 8.4kg of tritium already circulates in the Pacific, while Fukushima’s wastewater contains just 3g—a veritable drop in the ocean. And in the days following the first release, tests of seawater in the region did not detect tritium at all. According to an IAEA report (with a notable Chinese contributor), the release is sure to have “a negligible radiological impact on people and the environment.”

But the opportunity was too good to pass up. Knowing most citizens would never read the IAEA report, China’s leaders set about conjuring that old jingoistic demon. “By dumping the water into the ocean,” raged a Foreign Ministry statement, “Japan is spreading the risks to the rest of the world and passing an open wound onto the future generations of humanity. By doing so, Japan has turned itself into a saboteur of the ecological system and polluter of the global marine environment.”

Beijing announced that it would be suspending seafood imports not just from Fukushima, but from the whole of Japan. State media ran paid ads on Facebook and Instagram, attacking the Japanese decision. Chinese journalists reported that Sonoda Yasuhiro, an official who publicly drank treated water from Fukushima back in 2011, had since died of cancer. Such reports turned out to be greatly exaggerated (to channel Mark Twain for a moment) as Sonoda was soon giving interviews to Japanese media. A six-month-old video of dead fish floating off Japan’s west coast (Fukushima is northeast) began recirculating under a new title: Video on nuclear polluted water discharge in Japan.

For China’s nationalist hordes, the washing ashore of a single dead sea turtle was enough. The owner of a Japanese pub in southwest China filmed himself dismantling his own business: smashing bottles on the floor, tearing down anime posters—he swore that he would open a Chinese bistro instead. Municipal offices in Tokyo were plagued with abusive calls from Chinese citizens. In Fuzhou and Beijing, they queued for hours to buy bags of salt, supposing it would be useful for treating the radiation sickness they expected to soon suffer.

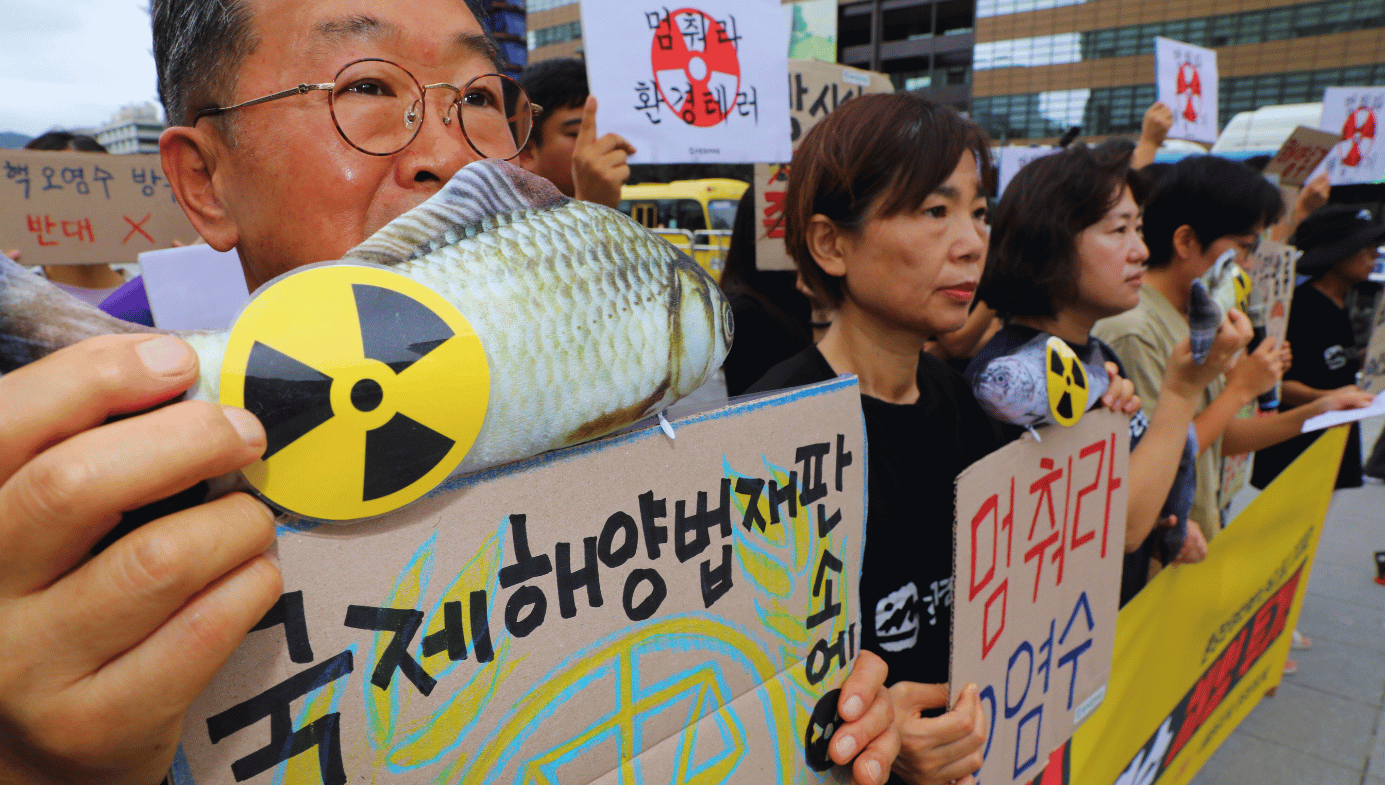

Fears are not confined to China: both Koreans and Japanese have also protested Tokyo’s actions. None of this should come as a surprise. Fear of contaminated water is probably one of our oldest instincts, and it’s perfectly natural to blanch at the prospect of radioactive waste. It’s also natural to respond emotionally to such news. Few of us have the time to properly research the topic. How many of those protesters read the IAEA report? How many knew that several kilograms of tritium were already drifting through the ocean, silently borne by warm currents long before the tsunami and nuclear disaster—before the earth began stirring, like an angry god deep beneath the Pacific floor, and the first trembling foreshocks came to the people of Japan?

The difference with the anger of Chinese nationalists is that this anger was already there, squatting inside their minds: just waiting for a reason, any reason. It will not listen to logic. “The world can survive with no Japan,” frothed a mainland acquaintance of mine, “but people can’t live without the ocean.”

That Foreign Ministry statement ended with a smug reminder for the country’s citizens: “The Chinese government always puts our people’s wellbeing first, and will take all measures necessary to safeguard food safety and the health of our people.” The Party assumes that China’s shrieking nationalists lack the independence of mind to do their own research. The Party assumes correctly. If they would only take a little time to look into the matter, the chauvinists would make some surprising discoveries.

In 2020, the Fuqing power plant on China’s east coast released nuclear wastewater containing two and a half times as much tritium as each planned annual Fukushima release. In 2021, the Qinshan power plant in Zhejiang province released 218 trillion becquerels of tritium—about ten times the Fukushima maximum. In fact, a total of 13 Chinese nuclear power plants have recently surpassed the Japanese levels. If Japan is to be accused of “sabot[aging] … the ecological system,” what are we to call this?

Allow me to speculate for a moment. Were Moscow or Pyongyang to authorise a similar release from Rostov or Taechon, the Chinese Foreign Ministry would suddenly begin making the most reassuring noises. And while a release from Cheonji or Wolseong in South Korea may trigger protests, no amount of Party propaganda could whip up anti-Korean feeling comparable to the public’s hatred for the Japanese. This syndrome is unique and unmistakable.

Beijing is playing a tricky—perhaps an impossible—game. With one hand it conjures rage in the populace; with the other it suppresses all outward manifestations of this rage. Those who decided to protest the wastewater release outside Japanese consular buildings in Chinese cities were quickly detained. No spontaneous public gatherings can be tolerated in communist China—not even demonstrations against the most hated of foes. The people are required to be angry at foreigners, but they are also required to stay indoors and nurse that anger within the safety of their own homes. Only the most impotent of rages is acceptable to the nervous autocrats in Beijing. Nationalism is just too dangerous a beast to be running around outside.

As the CCP knows only too well, these anti-Japan protests can get out of hand. Back in 2012, Chinese citizens erupted over the Japanese government’s move to buy the Senkaku islands from their private (Japanese) owners. China also claims the territories, and so large demonstrations raged through Beijing and Guangzhou (such a thing was still possible under China’s previous leaders). Chants of “smash Japanese imperialism!” echoed through the streets. Japanese flags were set alight, Japanese cars were overturned, a Japanese consulate had its windows smashed, and the Japanese embassy in Beijing was showered with eggs. Normally so strident, Party-controlled media were reduced to nervous throat-clearing: “Wisdom is needed in the expression of patriotism!”

China has plenty of manga fans and fans of Japanese culture in general. But in a nation of 1.28 billion, even a large minority can end up making about as much difference as three grams of tritium floating through the Pacific. Hatred of Japan infects all parts of society, spreading with as much virulence in the military as anywhere else. And of course, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has more than eggs and bricks in its arsenal. It has warned off regional assistance in the event of a Taiwan War, threatening—for Japan specifically—nuclear retaliation. Should Beijing triumph over Taipei, then even a carefully neutral Tokyo will not be safe, as internal PLA documents make terrifyingly clear:

As soon as Taiwan is reunified with Mainland China, Japan’s maritime lines of communication will fall completely within the striking ranges of China’s fighters and bombers. … Our analysis shows that, by using blockades, if we can reduce Japan’s raw imports by 15–20%, it will be a heavy blow to Japan’s economy. After imports have been reduced by 30%, Japan’s economic activity and war-making potential will be basically destroyed. After imports have been reduced by 50%, even if they use rationing to limit consumption, Japan’s national economy and war-making potential will collapse entirely. … Blockades can cause sea shipments to decrease and can even create a famine within the Japanese islands.

The repetition of that odd phrase “war-making potential” shows us the warped lens through which Beijing squints at the world. Imperial Japan defeated Qing China and Republican China in two historical wars, and these events haunt the imagination of all those educated by the Communist Party (schoolbooks place masochistic emphasis on atrocities accompanying the latter conflict). The Japanese, so the Party teaches, have not changed. They remain bellicose to the core, and will rain bloody havoc on China given the slightest chance. Japan must be neutralised.

The Chinese psyche is a complex prospect in 2023, home to diverse and contradictory currents. I’ve never seen so much anger at the central authorities, nor so much scepticism of the mainstream narrative—a direct result of Zero-COVID policy and the dramatic slowdown of the economy. Last year’s White Paper Revolution was the first tremor indicating a seismic change in the national consciousness. At the same time, chauvinism remains widespread and aggressive, coupled with an unshaking faith in the Party.

Equally widespread is a fatalism; a disengagement. Young middle-class Chinese are abandoning the hopeless struggle for success in the workplace. Instead, they are “lying flat” (tang ping)—a new social phenomenon greatly troubling to the authorities. Overworked and disillusioned, but unable to protest for obvious reasons, these people have opted to drop out. Their slogan: Don’t buy property; don’t buy a car; don’t get married; don’t have children; don’t consume.

While Beijing would have us believe in a Chinese hive mind (think of all that tedious hogwash about the “hurt feelings of the nation”), the truth is that the consciousness of the Chinese people is pulling in multiple different directions at the same time. Robotic xenophobes love the Party; newly awoken apostates hate the Party; worldweary fatalists don’t care about the Party. When we consider China today, there is cause for both hope and fear. The future is not set. But the first of those three groups—the syndrome-suffering group—presents us with an immense problem, numbering hundreds of millions of citizens. It will remain a danger long after the Party falls.