Politics

The Lab-Leak Illusion

The laboratory accident hypothesis of COVID-19’s origins is a bust, but the popular consensus is unwilling to accept it.

I. A Consensus Capsizes

On January 31st, 2020, Anthony Fauci, who was then director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Diseases, emailed the director of London’s Wellcome Trust with worrying news. Scripps Institute researcher Kristian G. Andersen, he wrote, was concerned that the genome of the novel coronavirus circulating in the Chinese city of Wuhan displayed unusual features suggestive of artificial manipulation:

I told [Kristian] that as soon as possible he and [Sydney-based evolutionary biologist] Eddie Holmes should get a group of evolutionary biologists together to examine carefully the data to determine if his concerns are validated. He should do this very quickly and if everyone agrees with this concern, they should report it to the appropriate authorities. I would imagine that in the USA this would be the FBI and in the UK it would be MI5.

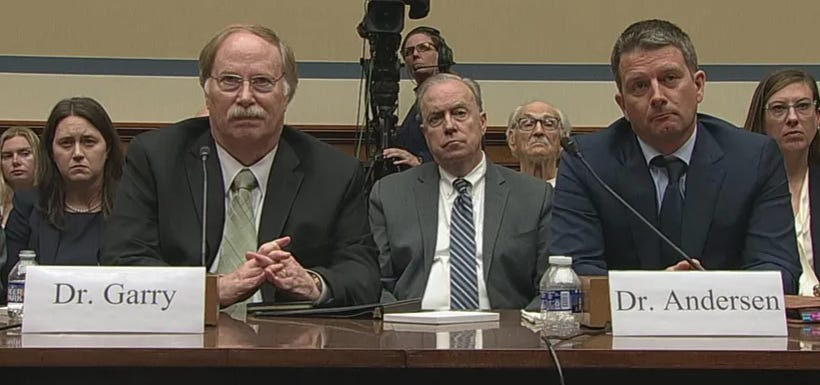

The following day, Andersen created a channel in the group-discussion app Slack and added Holmes, US microbiologist Bob Garry, and British evolutionary biologist Andrew Rambaut. In this forum, the four researchers would try to determine the most likely origins of the new virus. A 140-page archive of their deliberations, leaked in July of this year, has been the subject of some exceedingly unscrupulous and lazy reporting (with the latter tending to rely on the former). That’s a pity, because a fair-minded reading of the archive’s contents and chronology provides a fascinating insight into the scientific process and into how and why the thinking of its participants changed.

The discovery of a cluster of unknown pneumonia had been announced by Wuhan health authorities on December 31st, 2019. Neither the disease (which would come to be called COVID-19) nor its causative agent (the coronavirus that would come to be called SARS-CoV-2) even had a name yet. The four researchers were therefore working with limited data in a climate of great uncertainty, and they debated the possibility of a lab escape for days. They were particularly concerned by apparent anomalies in the viral genome—its “furin cleavage site,” a component of the virus that increases infectivity, and a receptor binding domain (RBD) that appeared to be optimised for attacking human cells.

“The furin site,” Andersen pointed out on February 1st, “is peculiar and (for now) unexpected, but we have a large ascertainment bias.” Eddie Holmes agreed, remarking that the genome was “exactly what would be expected from engineering.” The Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) was known to have isolated and experimented with coronaviruses and Andersen worried that a novel pathogen might have been created by passing a progenitor repeatedly through cell culture.

But as they sifted the existing coronavirus literature and absorbed the rapidly emerging studies, preprints, news reports, and viral sequences, the researchers discovered that the features of SARS-CoV-2 that initially puzzled them were not as unusual as they had thought. Furthermore, the closest relative of the virus known to be held by the WIV was too distantly related to have provided the backbone for an engineered chimera.

They could not definitively prove a lab-leak negative, but since the constituent parts of the virus could all now be accounted for by evolution, the more parsimonious explanation was that the virus had evolved naturally. “I’m now very strongly in favour of a natural origin,” Holmes told his Slack-channel colleagues on February 25th. “The component bits of the virus are now more or less there in a tiny sample of wildlife. … I don’t see why we need a lab origin on these data.”

On March 17th, 2020, they presented their review of the evidence in a short paper titled “The Proximal Origin of SARS-CoV-2,” which was published in the correspondence section of Nature Medicine as a letter to the editor. It concluded:

Although the evidence shows that SARS-CoV-2 is not a purposefully manipulated virus, it is currently impossible to prove or disprove the other theories of its origin described here. However, since we observed all notable SARS-CoV-2 features, including the optimized RBD and polybasic [furin] cleavage site, in related coronaviruses in nature, we do not believe that any type of laboratory-based scenario is plausible.

More scientific data could swing the balance of evidence to favor one hypothesis over another.

These conclusions were generally well received. Back in 2020 and early 2021, the lab-leak hypothesis was still a fringe view, generally associated with the paranoid fever swamps of the MAGAsphere and the craziest China hawks in the Trump administration, the president included. Some of those voices believed that SARS-CoV-2 had been developed by the CCP as a bioweapon. Others believed it might even have been released deliberately. Although good information remained hard to come by, the low-risk editorial assumption across most of the media seemed to be that if Donald Trump, Tucker Carlson, and Steve Bannon found a lab leak plausible, it was probably populist demagogy intended to embarrass China and divert attention from the president’s own chaotic pandemic response.

That assumption appeared to receive authoritative support from Andersen et al.’s review. But elsewhere, independent researchers were conducting a dogged investigation of their own, and posting their theories on preprint servers, blogs, and social media. In February 2020, 30 of these researchers formed an online collective calling itself DRASTIC (Decentralized Radical Autonomous Search Team Investigating COVID-19). A couple of months later, a Canadian biotech entrepreneur and DRASTIC co-founder named Yuri Deigin posted an influential 16,000-word essay on Medium, in which he argued that SARS-CoV-2 may well have been genetically engineered.

These were not MAGA Republicans; they were concerned citizens, academics, and scientists, and they offered a less outlandish version of the lab-escape hypothesis. The SARS-CoV-2 virus, they argued, was not a bioweapon, but a product of well-intended but dangerous “gain-of-function” research, which involves artificially increasing the transmissibility and virulence of pathogens in a laboratory in the hope of developing a multipurpose vaccine. Curious journalists and writers began to take notice of DRASTIC’s work, and the first big piece in a mainstream outlet defending this version of events appeared on New York magazine’s Intelligencer website on January 4th, 2021. In a 12,000-word essay, novelist Nicholson Baker set out his theory of the pandemic’s origins like this:

It was an accident. A virus spent some time in a laboratory, and eventually it got out. SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, began its existence inside a bat, then it learned how to infect people in a claustrophobic mine shaft, and then it was made more infectious in one or more laboratories, perhaps as part of a scientist’s well-intentioned but risky effort to create a broad-spectrum vaccine. SARS-2 was not designed as a biological weapon. But it was, I think, designed.

Baker’s piece attracted some interest and commentary, but it was a Medium essay by former New York Times science writer Nicholas Wade that finally ended media resistance to the lab-leak idea. Wade’s conclusion was similar to Baker’s, but he supported his argument with a granular analysis of SARS-CoV-2’s molecular biology, and he did not hesitate to name the guilty men he held responsible for the unfolding global catastrophe. These included the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), researchers at the WIV, the “worldwide community of virologists,” and US public-health officials and scientists who had helped to fund the WIV’s work.

Wade’s argument probably benefited from Donald Trump’s electoral defeat in November 2020, which provided the debate about COVID origins with some breathing room. And now that vaccines were on the way and societies were starting to reopen, editors, diplomats, and politicians were no longer preoccupied by the ceaseless quarrels over pandemic containment. When his essay was self-published on May 3rd, 2021, it was widely shared, endorsed, and discussed. And when it was cross-posted at the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists two days later, it was widely shared, endorsed, and discussed all over again.

Editors at mainstream publications awoke to find that a hypothesis they had spent a year and a half dismissing as paranoid gibberish was being promoted all over social media by respected journalists and public figures. The prevailing consensus among opinion-formers capsized with astonishing rapidity. On May 17th, Politifact retracted a fact-check from the previous September, which had described the claim that SARS-CoV-2 was a “man-made virus made in the lab” as “inaccurate and ridiculous.” Days later, Meta announced that Facebook would be lifting the draconian ban it had imposed in February 2021 on sharing lab-leak-related content on its platforms.

The media’s gatekeepers threw open their doors. On June 3rd, Vanity Fair published a 12,000-word account of “the fight to uncover COVID-19’s origins.” The Week published a 6,000-word essay by a member of the DRASTIC collective in July. A breathless essay appeared in Newsweek setting out the case for a lab accident, followed by a more measured article in the New York Times. On August 22nd, Britain’s Channel 4 broadcast a 47-minute documentary titled “Did COVID Leak from a Lab in China?” (a question to which the implied answer was “probably”). In November, Broad Institute scientist Alina Chan and British science writer Matt Ridley set out the case for a lab accident in their book Viral, and then toured the podcast circuit energetically promoting their conclusions.

According to the newly received wisdom, anyone who hadn’t suspected a lab leak all along was either a CCP stooge or painfully obtuse. Scientists who maintained that the virus was more likely to have spilled into humans from another species were thrown onto the defensive. Kristian Andersen gave an interview to the New York Times defending the “Proximal Origin” review, and on social media, virologists found themselves forced to defend their professional reputations and the legitimacy of their research from accusations that they were responsible for a pandemic that had already claimed millions of lives.

Almost overnight, Nicholas Wade had managed to turn a low-status belief into a high-status belief, held by the public and elites alike. It has remained that way ever since, particularly in the US. Polling reported by the Washington Post in March 2023 found that overwhelming majorities of Americans now endorse the lab-leak hypothesis of COVID origins. Influential voices on the Left, Right, and centre continue to support it and the GOP has brought the two US-based “Proximal Origin” authors before a Congressional committee to answer allegations of deliberately misleading public opinion.

All of which is odd, since a natural origin is better supported today than it was when the “Proximal Origin” paper appeared in early 2020. Evidence for a lab accident, meanwhile, remains conspicuously absent.

I started to take an interest in this debate after Quillette published Philippe Lemoine’s critical examination of the lab-leak hypothesis in late 2020. I began following advocates on both sides of the argument on social media, I read Chan and Ridley’s book, as well as papers, preprints, blogs, and articles, and I kept an eye on (but did not participate in) the endless discussion threads devoted to the topic proliferating across social media. And by the time I reached saturation point, I’d concluded that, popularity notwithstanding, the lab-leak hypothesis simply doesn’t add up.

In what follows I want to explain why. I am neither a scientist nor a science writer, so this will not be a technical essay. Nor will I be offering any original research. This will be a critical analysis of the debate along with some concluding thoughts about how and why the discourse on this topic has diverged so sharply from the available evidence. Although gaps remain in the natural hypothesis of COVID-19’s origins, the lab-leak alternative is poorly supported and internally incoherent. The debate only continues because popular consensus is not yet ready to accept this.

II. The Wuhan Labs

The most intuitively compelling argument for a lab accident relates to the proximity of the lab to the outbreak, and it goes something like this:

- A coronavirus pandemic began in Wuhan.

- Wuhan has multiple virology laboratories studying coronaviruses.

- Therefore, the pandemic was almost certainly caused by a laboratory accident.

This isn’t really evidence—it’s a claim about how we ought to evaluate our priors in the absence of any other information. On the eve of the pandemic, there were two possible routes by which a respiratory virus that originated in bats in rural southern China might reach the central metropolis of Wuhan. It might be sampled during fieldwork by scientists and transported back to a Wuhan lab for research purposes. Alternatively, the virus might be carried into one or more of the city’s four wet markets by the illegal wildlife trade. A probability assessment that ignores the presence of wet markets makes no more sense than one that ignores the presence of virology labs. And before any pandemic data became available, there were already good reasons to prefer the market hypothesis.

First, virology labs are a lot safer than wet markets because lab researchers are trained to handle dangerous pathogens and it is in their interests to adhere to strict biosafety protocols governing the research and storage of viruses. That is not to say that accidents never happen. They do. But a priori, a spillover is much more likely to result from the unregulated trade in known vectors of disease than from an accident in a tightly controlled environment. As Lemoine noted, very few people work in virology labs while millions of rural Chinese (not to mention many millions more susceptible animal hosts) are potentially exposed to coronaviruses every year. It is also worth bearing in mind that while the WIV has one of the world’s largest collections of coronaviruses, those samples represent a minute fraction of those circulating in the wild.

Second, a natural (or “zoonotic”) spillover is supported by copious historical precedence as well as recent experience. 2009 H1N1, Ebola, HIV, SARS, and MERS all spilled from animals into humans without ever seeing the inside of a virology lab, as did countless pathogens before them. Like SARS-CoV-2, the SARS outbreak in 2002–03 occurred hundreds of miles from the bat colonies in which the virus originated. It is thought to have spilled from bats into an intermediate host—probably palm civets—which were then transported to wildlife markets in China’s Guangdong Province. There, they infected the traders and customers, who in turn infected their families and colleagues causing an epidemic that eventually spread to 30 countries killing at least 774 people and sickening thousands more.

Before the SARS pandemic, most opposition to China’s wildlife trade was focussed on animal welfare. The discovery that it could also pose a mortal threat to public health threw a multibillion-dollar industry into crisis. On April 29th, 2003, China’s State Forestry Bureau announced a national ban on wildlife trading and consumption, and in the ensuing crackdown, hundreds of thousands of wild animals were confiscated and destroyed, and thousands of breeders, transporters, and vendors found their livelihoods plunged into uncertainty.

The preventative measures would not last, however, and in a paper for the Environmental Policy and Law journal, published on December 21st, 2021, Peter Li argued that the ban never stood a chance:

The [Chinese Communist] Party’s set policy of elevating the national economy from the old and resource-exploitative model of production to a sustainable development model offered the wildlife industry a good opportunity to expand and intensify. The Party’s policy guidelines also gave the national and local forestry bureaus a golden opportunity to seek a budgetary expansion in anticipation of greater regulatory responsibilities. The SARS pandemic and the trade ban were an unexpected threat to both the industry and the administrative agencies.

Sustained lobbying by the industry found a sympathetic ear in the CCP, which believed the trade in wildlife to be an engine of rural economic regeneration, and in August 2003, the national ban on wildlife trade and consumption was rescinded. Trading resumed, and when Eddie Holmes visited the Huanan market in late 2014, he found caged wild animals being illegally sold for food, including coronavirus-susceptible raccoon dogs. “By the end of 2017,” Li reported, “the wildlife industry had become a gigantic business operation with an annual revenue of 520 billion yuan (US $77 billion).”

When the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission announced the discovery of a cluster of novel pneumonia on December 31st, 2019, an epidemiological link to the city’s Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market had already been established. No epidemiological link has since been found to any other location in the city. Chinese authorities revealed that a novel coronavirus was the causative agent of the new disease on January 7th, and the SARS-CoV-2 genomic sequence was released three days later. When human-to-human transmission was confirmed by China’s Health Ministry on January 20th, it opened up the possibility that the Huanan market was merely the site of a superspreader event, not a spillover.

But this hypothesis began to look more improbable as we learned about the manner in which SARS-CoV-2 spread. Like other coronaviruses, community transmission of wild-type SARS-CoV-2 occurred mostly in clusters, with roughly 10 percent of cases responsible for 80 percent of infections. Adam J. Kurchaski, an associate professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, told Science in May 2020 that “most chains of infection die out by themselves and SARS-CoV-2 needs to be introduced undetected into a new country at least four times to have an even chance of establishing itself. … If the Chinese epidemic was a big fire that sent sparks flying around the world, most of the sparks simply fizzled out.”

It is therefore unlikely (though not impossible) that a single market visitor would have infected enough people to ignite an epidemic. In Wuhan’s wet markets, on the other hand, distressed wild animals were trapped in cramped and unsanitary conditions in an enclosed environment through which thousands of people of all ages and susceptibilities passed each day. If any of those animals were infected with SARS-CoV-2, the stalls selling and butchering them would have turned the market into a focus of infection, seeding cases in the surrounding neighbourhood just as the Broad Street water-pump seeded a cluster of cholera cases during the 1854 epidemic in London. In a densely populated city and transportation hub like Wuhan, such a focus of infection would create the ideal conditions for a pandemic.

In June 2021, Xiao and colleagues published the results of a survey of Wuhan’s live-animal markets, which one of the authors had conducted between May 2017 and November 2019. Their findings confirmed the presence of susceptible wildlife at the Huanan market and the dangerous conditions in which they were kept for sale and slaughter. “Across all 17 shops,” the authors wrote, “vendors reported total sales of 36,295 individuals, belonging to 38 terrestrial wild animal species, averaging 1170.81 individuals per month.”

Almost all animals were sold alive, caged, stacked and in poor condition. Most stores offered butchering services, done on site, with considerable implications for food hygiene and animal welfare. Approximately 30% of individuals from 6 mammal species inspected had suffered wounds from gunshots or traps, implying illegal wild harvesting.

This was plainly a disaster waiting to reoccur, if not in Wuhan in 2019, then at another wet market in another Chinese city, irrespective of whether or not that city happened to host one or more virology laboratories. Widespread suspicion that the Wuhan epidemic originated in one of the city’s wet markets was not an arbitrary bit of misdirection, it was simply the most logical inference from the information then available. The emergence in 2019 of a novel coronavirus in a Chinese city with four wet markets trading susceptible wild animals most obviously suggested a recurrence of 2002–03. Even the Chinese CDC believed this to be the case.

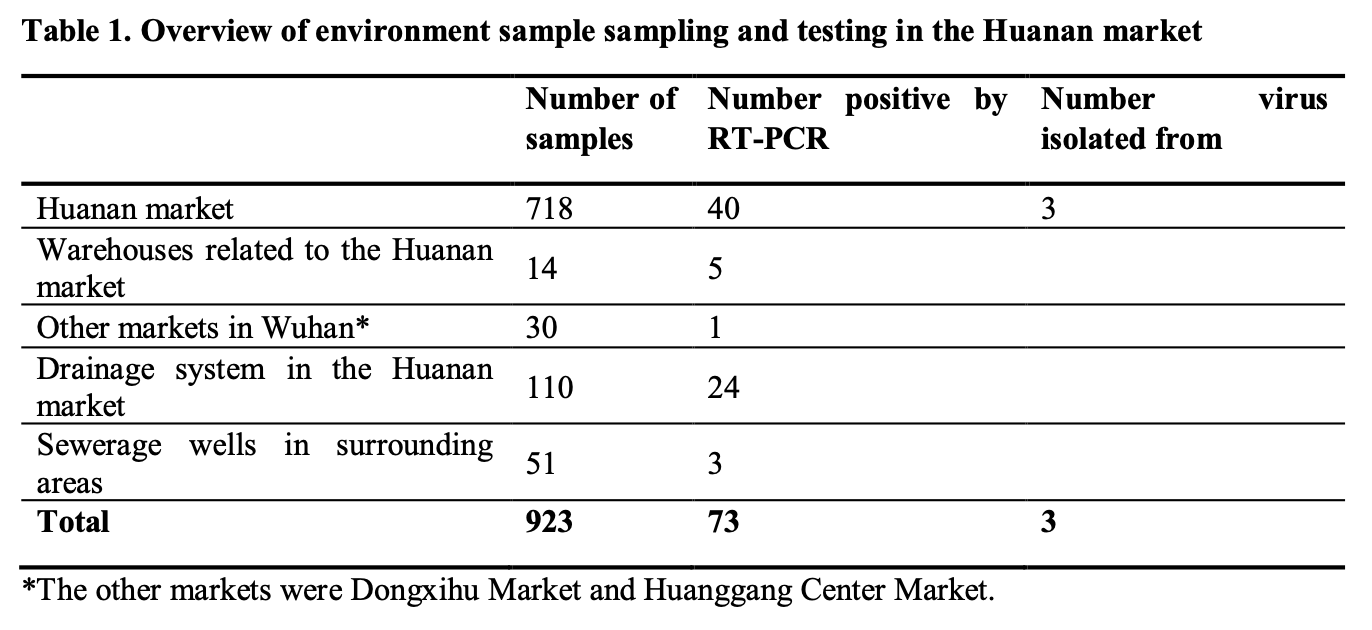

It has now been conclusively established that the virus was in the market in December 2019. Environmental swabs collected there by the Chinese CDC between January 1st and March 2nd, 2020, yielded 40 positive results, from which three live samples were isolated. By the time the CDC arrived, disinfection teams dispatched by the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission in the early hours of December 31st had already begun the clean-up operation. The Wall Street Journal subsequently reported that some of the solution used was so powerful that it corroded the disinfection equipment. That any positive samples were recovered at all indicates that the market was awash with virus before the clean-up operation began.

The 2021 WHO-China investigation into COVID origins found that positive environmental samples were clustered in the west of the market, where live-animal stalls were situated and where a number of early COVID patients worked. Previously unreported genomic data from the Chinese CDC’s environmental samples, fortuitously obtained by Western researchers in March 2023, have confirmed that COVID-susceptible wildlife, including raccoon dogs, was being traded in the Huanan market when the outbreak began. The illegal wildlife trade was able to deliver them from rural China right into what would become the epicentre of the outbreak. In accordance with the principle of parsimony (aka Occam’s Razor), the only further assumption we need to make is that some of those animals were infected when they arrived.

The lab-leak hypothesis, on the other hand, requires a two-stage trip from rural China to the market via the lab. And the second stage of that journey requires a further chain of ad hoc assumptions, every one of which has to be correct and not one of which is presently supported by any evidence. A lab researcher either (a) successfully isolated and cultured the SARS-CoV-2 virus or its proximal ancestor (which the lab also had the wherewithal to turn into SARS-CoV-2) or (b) synthesised a novel virus from an existing genomic sequence. Then one or more researchers became infected in some unspecified way without their knowledge and visited the Huanan Seafood Market when they were contagious without seeding an outbreak at the WIV itself or in the surrounding neighbourhood.

And all these assumptions rest on the biggest assumption of all—that a live sample of the SARS-CoV-2 virus (or its proximal ancestor) was actually inside a Wuhan virology lab in the first place. Nobody has yet provided any evidence that it was (or that it was inside any laboratory anywhere in the world) prior to the discovery of a novel pathogen in Wuhan in December 2019. Until this is demonstrated, all subsequent assumptions can be chopped away with Occam’s razor and discarded.

III. The Argument from Design

The argument from design holds that features of the SARS-CoV-2 genome are so rare or eerily well-adapted that they indicate the hand of an intelligent designer rather than the adaptive pressures of natural selection. In his May 2021 Medium essay, Nicholas Wade contended that one such feature is the furin cleavage site that had spooked Kristian Andersen and his “Proximal Origin” colleagues. While Wade allowed that the furin cleavage site could also have evolved naturally, unlike Andersen et al., he came down on the side of genetic engineering.

Wade concluded this section of his essay with an arresting claim from David Baltimore, a virologist whose research into viral genetics has been rewarded with a Nobel Prize. Baltimore told Wade that when he saw the furin cleavage site in SARS-CoV-2, he believed it to be “the smoking gun for the origin of the virus,” and “a powerful challenge to the idea of a natural origin.” That short quote probably did more than anything else in Wade’s 11,000-word essay to electrify the debate about COVID origins. The authority of Baltimore’s reputation carried considerable weight and suggested that Wade’s arguments were scientifically decisive.

In a long Twitter thread answering the Baltimore quote, Andersen reiterated the conclusions of the “Proximal Origin” review, pointing out that while none of the closest known relatives of SARS-CoV-2 has a furin cleavage site, it is “abundant” in coronaviruses generally, including in the betacoronavirus genus to which SARS-CoV-2 belongs. “There is nothing mysterious about having a ‘first example’ of a virus with an FCS,” he wrote. “Viruses sampled to date only give us a teeny-tiny fraction of all the viruses circulating in the wild.”

In an interview the following month, David Baltimore was asked directly about his “smoking gun” quote and admitted that he had overstated the case. “Let me be clear,” he said, “even though I used the phrase ‘smoking gun,’ I don't really think there's a smoking gun in the genome itself.” Given its prevalence in other betacoronaviruses, he went on to explain, the furin cleavage site could well have evolved naturally. It could also have been manually inserted, but he conceded that it is not possible to tell one way or the other simply by looking at the genome.

Two years later, a paper in Virologica Sinica reported the identification of two new bat betacoronaviruses (BtCoV CD35 and CD36) in China’s southernmost Hainan province, one of which “harbored a canonical furin-like S1/S2 cleavage site that resembles the corresponding sites of SARS-CoV-2.” This discovery, the authors wrote, “deepens our understanding of the diversity of coronaviruses and provides clues about the natural origin of the furin cleavage site of SARS-CoV-2.” Importantly, it provided a reminder that our understanding of “coronavirus ecology in bats is still nascent.”

When virologist David Robertson was approached by Wade for comment, he had tried to explain this. “Viruses are specialists at unusual events,” he told Wade. “Recombination is naturally very, very frequent in these viruses,” he added, and if features of a particular virus appeared to be unusual, this was likely because “we’ve not sampled enough.” But Wade didn’t like the implications of Robertson’s argument:

This argument could be pushed too far. For instance any result of a gain-of-function experiment could be explained as one that evolution would have arrived at in time.

This is probably true, given how poorly the true scope and diversity of coronaviruses are understood and the regularity with which co-infection produces recombination events in bats and other animal hosts and reservoirs. But that is why a convincing case for a lab leak needs to be backed by its own evidence as well as speculation about the unlikelihood of the alternative.

In late September 2021, members of the DRASTIC collective believed they had found such evidence when they obtained and released a grant proposal entitled DEFUSE. The proposal had been submitted to the US Defense Research Projects Agency in 2018 by Peter Daszak’s New York-based nonprofit, the EcoHealth Alliance (EHA). The EHA had already collaborated on coronavirus research and experimentation projects with Shi Zhengli’s lab at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. Now, Daszak’s organisation was seeking $14,209,245 for additional research, the stated purpose of which was “to defuse the future potential for spillover of novel bat-origin high-zoonotic risk SARS-related coronaviruses in Asia.”

Inter much alia, page 13 of this dense and lengthy document included the following three sentences:

We will analyze all SARS-CoV S gene sequences for appropriately conserved proteolytic cleavage sites in S2 and for the presence of potential furin cleavage sites. SARS-CoV with mismatches in proteolytic cleavage sites can be activated by exogenous trypsin or cathepsin L. Where clear mismatches occur, we will introduce appropriate human specific cleavage sites and evaluate growth potential in Vero cells and HAE cultures.

These esoteric lines were generally agreed to mean that Daszak and his partners wanted to insert a furin cleavage site (or something very like it) into the backbone of another coronavirus at the precise point at which it appeared in the SARS-CoV-2 genome. From this, lab-leak theorists concluded that SARS-CoV-2 had been engineered using American grant money before it escaped from the WIV. Daszak knew this, they alleged, and a statement published by the Lancet on February 19th, 2020, which he had organised and co-signed, dismissing the lab-leak hypothesis as a conspiracy theory, was a disgraceful attempt to shut up those who were getting uncomfortably close to the truth.

There were at least three problems with this narrative. First, the DEFUSE proposal indicated that the engineering work was to be conducted by Ralph Baric at the University of North Carolina, and not in Wuhan. Second, none of the coronaviruses that we know the WIV possessed could have been used as a backbone to make SARS-CoV-2 in this way, which makes the DEFUSE proposal irrelevant to the question of COVID origins. And third, the grant proposal was rejected, the funding was denied, and so the experiment was never conducted anyway.

Lab-leak theorists like to speculate that the work went ahead regardless, but they have no evidence of this and Daszak and the EHA have repeatedly denied it. Theorists further speculate that the WIV had undisclosed coronaviruses in its holdings which could have been turned into SARS-CoV-2, and that this work was being kept secret for reasons unexplained. But there’s no evidence for any of that either, and we’re now simply stacking conjecture on conjecture—further make-work for Occam’s Razor.

IV. The Story of the Copper Mine

In 2012, six workers tasked with clearing bat guano out of a derelict mine shaft in Mojiang County, Yunnan province, fell sick with SARS-like symptoms—cough, dyspnoea, muscle aches, and fever. Half of them died. Three teams of virologists, including a WIV team led by Shi Zhengli, made multiple visits to the mine between August 2012 and July 2013 to gather samples, but they were unable to identify the causal agent of this mysterious illness. In a paper published in Virologica Sinica on February 18th, 2016, Ge et al. reported the results of that surveillance—276 bats sampled from six species, half of which tested positive for coronaviruses. Partial sequences of two new betacoronaviruses were obtained, and one of these, detected in a fecal sample obtained from a horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus affinis), was labelled RaBtCoV/4991.

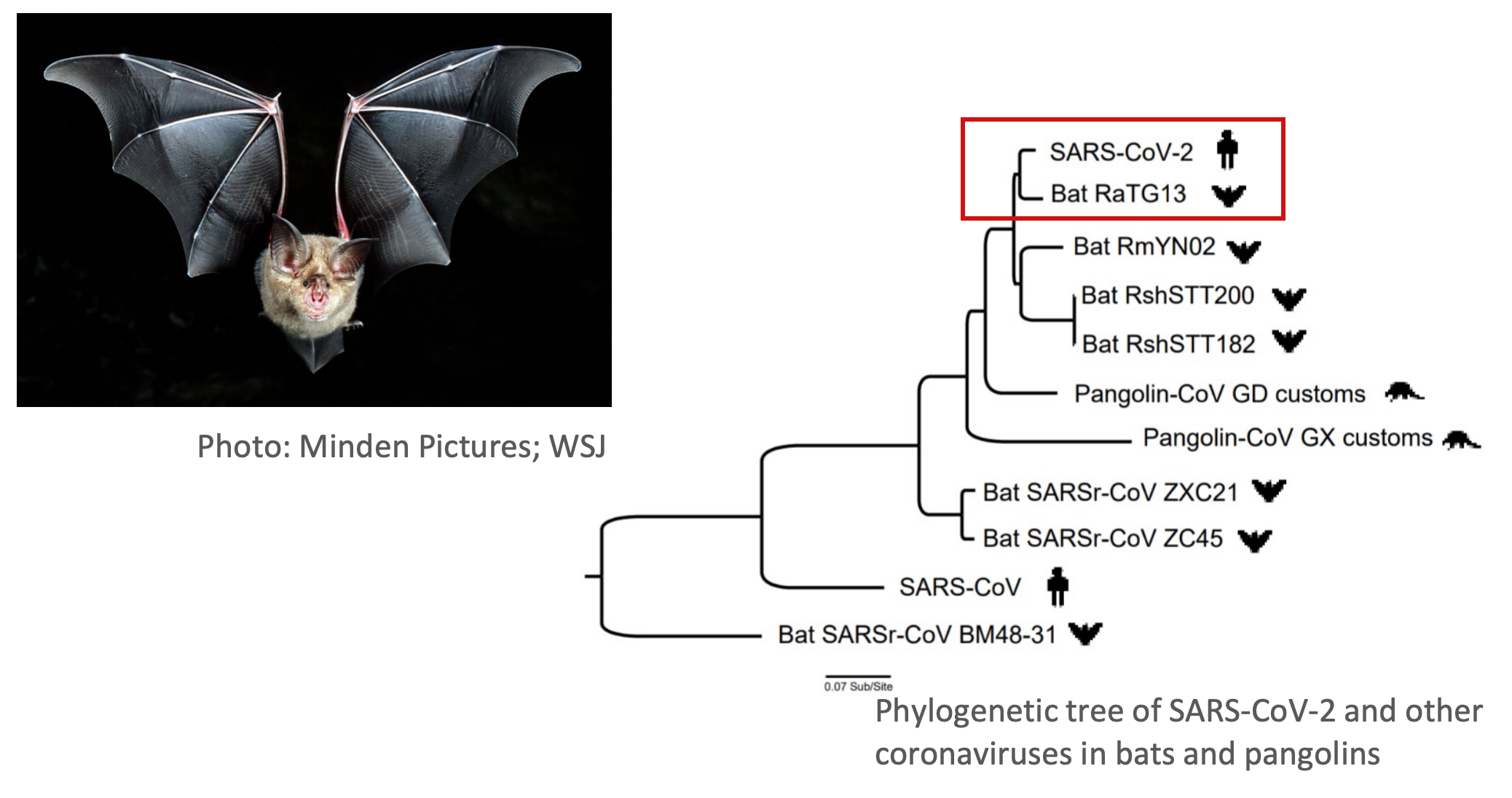

Eight years later, in February 2020, as COVID-19 swept through Wuhan, Zhou et al. published a paper in Nature titled, “A Pneumonia Outbreak Associated with a New Coronavirus of Probable Bat Origin.” The authors (who included Shi) reported that SARS-CoV-2 had a 96.2 percent match with the genome of betacoronavirus BtCoV RaTG13 “which was previously detected in Rhinolophus affinis from Yunnan province.” This made RaTG13 the closest known relative to SARS2—evidence, the authors determined, “that 2019-nCoV [SARS-CoV-2] may have originated in bats.”

In early March 2020, an Italian microbiologist named Rossana Segreto figured out that the sample BatCoV/4991 (mentioned in the 2016 paper about the Mojiang mine) and RaTG13 (mentioned in the February 2020 paper about SARS-CoV-2) were the same virus, even though there was no citation in the latter paper making this explicit. Then in May, a DRASTIC researcher discovered a 2013 Master’s thesis by Xu Li, who had been studying at the hospital in Kunming where the ailing mine workers were treated. Xu’s paper told the story of the six labourers and discussed their symptoms and treatments in some depth. It concluded that they had probably been infected by a SARS-like coronavirus.

DRASTIC researchers found all this deeply suspicious. Why had Shi Zhengli not mentioned the sick mine workers in the 2016 paper reporting her team’s surveillance of the mine? Why was a citation of the 2016 paper missing in the 2020 paper? And why did this virus—the closest known relative to SARS-CoV-2—have two names? They concluded that Shi was trying to conceal the fact that SARS-CoV-2 had been artificially created from RaTG13. In his Intelligencer essay, Nicholson Baker described the story of the mine as a matter of “exceptional importance” and summarised what he thought may have happened like this:

[I]n the climate of gonzo laboratory experimentation, at a time when all sorts of tweaked variants and amped-up substitutions were being tested on cell cultures and in the lungs of humanized mice and other experimental animals, isn’t it possible that somebody in Wuhan took the virus that had been isolated from human samples, or the RaTG13 bat virus sequence, or both (or other viruses from that same mine shaft that Shi Zhengli has recently mentioned in passing), and used them to create a challenge disease for vaccine research—a chopped-and-channeled version of RaTG13 or the miners’ virus that included elements that would make it thrive and even rampage in people? And then what if, during an experiment one afternoon, this new, virulent, human-infecting, furin-ready virus got out?

On social media, virologists were exasperated by this theory and aghast at the attention it was receiving from the mainstream press. In a June 2021 Twitter thread, King’s College London virologist Stuart Neil was categorical: “[SARS-CoV-2] is not the result of passage or directed evolution of RaTG13, and cannot be derived from the so-called [gain-of-function] work the WIV was doing with the TOOLS WE KNOW THEY HAD.” Neil stressed that you don’t even need to be a scientist to grasp this point, you just need to be able to read a family tree—someone’s cousin cannot also be their parent.

By the time of that thread, the goalposts were already being moved. Segreto and others were now speculating that BatCov4991 and RaTG13 were perhaps not the same virus after all, and that BatCoV4991 might be the common ancestor to both RaTG13 and SARS-CoV-2. “I like these discussions,” Neil told Segreto. “[W]hat I struggle with is the propensity of some to throw entire scientific disciplines out because it doesn’t give them the answer they want.”

In a faintly impatient paper published in September 2021, Frutos et al. upheld Neil’s view:

RaTG13 is not a virus but only a sequence generated by metagenomics. Therefore, there is no evidence that this sequence corresponds to any real and viable virus or even that all reads are coming from the same virus. The RaTG13 sequence might also be a chimera with fragments coming from different viruses. RaTG13 has never been isolated as a virus and replicated in cell cultures. It has no physical existence and thus cannot leak from a laboratory.

Nor could it be made into SARS-CoV-2. Period. As for the mine workers, the authors cautioned that the pathogen that caused their illness had never been conclusively identified, and might not have been a bat coronavirus at all. In any event, it was definitely not SARS or SARS-CoV-2. Although some of the workers tested positive for SARS antibodies, one of them did not. And although they exhibited some symptoms consistent with a SARS-CoV-2 infection, they exhibited many other symptoms that were not. “[T]here is no evidence,” the authors concluded, “to support the Mojiang mine origin of SARS-CoV-2 and any of the laboratory leak theories.”

Frutos et al. submitted their paper in July 2021. By the time it was published in September, the debate about the mine had already been consigned to obsolescence. Four days earlier, an article in Nature had reported that, “Scientists have found three viruses in bats in Laos that are more similar to SARS-CoV-2 than any known viruses.” With the supposedly incriminating link between SARS-CoV-2 and RaTG13 now superseded by the discovery of closer relatives, there was no longer any reason to pay particular attention to the Mojiang mine. China is a big place with a lot of caves and a lot of bat colonies carrying many thousands of unsampled viruses. The Laos discovery provided a timely reminder of just how little we know about them.

Besides which, if this was a cover-up, it was hopelessly incompetent—all that DRASTIC needed to connect the puzzle pieces was Google and a bit of initiative. As Florence Débarre, a Parisian molecular biologist professionally involved in the investigation of COVID origins, has pointed out, all the information uncovered about the mine and its relationship to RaTG13 “was easy to find for basically any biologist who wanted to know.” And Shi gave them all a big assist by revealing the existence of RaTG13 and its genomic similarity to SARS-CoV-2 in her 2020 paper. Why would she disclose that information if it was likely to implicate her lab as the source of the pandemic?

The debate about the Mojiang mine didn’t yield anything useful about COVID origins, but it did expose something useful about the limits of scientific dilettantism. DRASTIC members are all intelligent, motivated, and resourceful people, and they possess an impressive ability to rapidly absorb new information. But a little knowledge is a dangerous thing—careful research requires time and effort and costs money, while autodidacticism is often unstructured, and understanding tends to be acquired on a need-to-know basis. This can leave important gaps that the autodidact doesn’t know are there. Consequently, DRASTIC (and their journalistic conduits) had greatly overestimated what could be accomplished in a modern virology laboratory and greatly underestimated the vast diversity of unsampled coronaviruses in the wild.

The collapse of the Mojiang mine story ought to have prompted a rethink from at least some of its advocates. After all, this was not just one of several promising lines of inquiry, it was the foundation of the entire narrative linking SARS-CoV-2 to the Yunnan caves through the WIV. Without it, the whole lab-leak hypothesis had been knocked back to square one. But by this point, the lab leak was no longer just a hypothesis, it had become a conviction, the evidence for which must be out there somewhere. And if it wasn’t to be found in the Mojiang mine… well, then it would have to be found somewhere else.

V. The Lab Safety Question

In April 2020, the Washington Post’s national-security reporter Josh Rogin reported that US Embassy officials in China had sent two diplomatic cables to the State Department in 2018 warning of “grave safety concerns at the WIV lab, especially regarding its work with bat coronaviruses.” The sourcing in Rogin’s article was confusing. At one point, he said he had “obtained” the first of these cables, and at another, he attributed their contents to “sources familiar with” them.

Either way, as Philippe Lemoine pointed out in his Quillette essay, Rogin managed to completely misunderstand and/or misrepresent both the tenor and the substance of these documents. When the State Department released the cables in July 2020, they did not bear out the alarmism of Rogin’s reporting nor that of the anonymous officials he quoted. Only the first cable was relevant to Rogin’s reporting, and it merely said this:

This state-of-the-art facility is designed for prevention and control research on diseases that require the highest level of biosafety and biosecurity containment. Ultimately scientists hope the lab will contribute to the development of new antiviral drugs and vaccines, but its current productivity is limited by a shortage of the highly trained technicians and investigators required to safely operate BSL-4 laboratory and a lack of clarity in related Chinese government policies and guidelines.

As the director of health and biosecurity at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization told the Post when he was approached for comment, “There is a continued global challenge in maintaining the appropriately skilled workforce. All [such] facilities around the world face this challenge.” On the whole, the cable’s authors appeared to be impressed by the surveillance and research conducted at the WIV and anxious that it continue.

In any case, the cable was reporting on the status of the WIV’s BSL-4 lab, in which only the most dangerous viruses are studied. Research on SARS-like coronaviruses was permissible in BSL-2 and BSL-3 labs (depending upon the kind of research), so even if “grave doubts” had existed among US embassy staff about the safety of the BSL-4 lab, these would be unlikely to have had any bearing on the COVID origins debate.

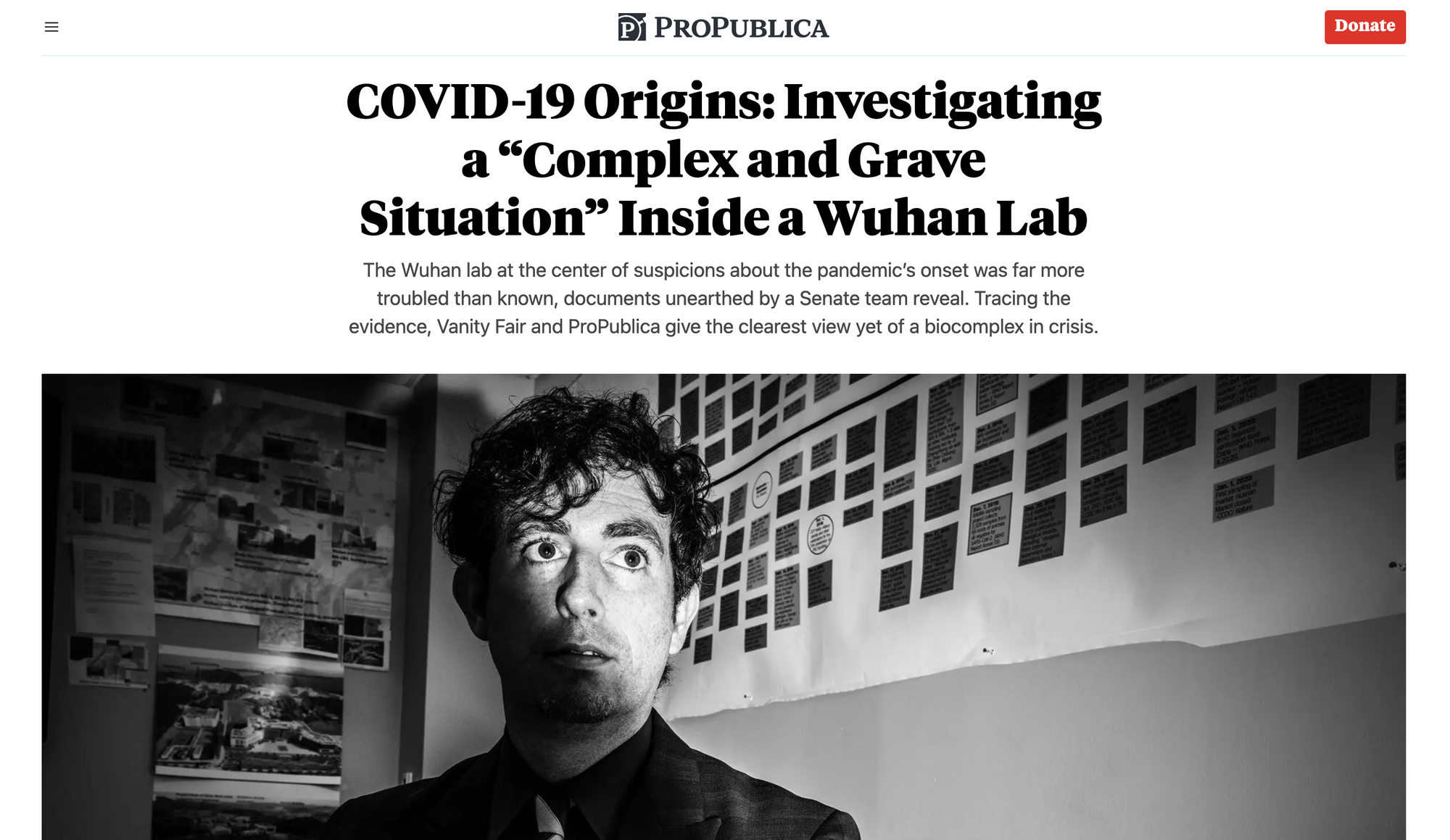

In October 2022, the WIV’s BSL-4 lab found itself at the centre of speculation again when ProPublica and Vanity Fair co-published a lengthy investigative report bylined (respectively) by Jeff Kao and Katherine Eban. An analyst named Toy Reid, who was then working with a US Senate Committee’s investigation into COVID-19’s origins, alleged that the WIV had “faced an acute safety emergency in November 2019.” The crisis had apparently provoked alarm at the very highest levels of the CCP, and a senior biosecurity apparatchik had been dispatched to Wuhan by Xi Xinping himself to read the riot act.

The nature of this biosecurity breach was unspecified in the 10,000-word article and nothing was adduced to indicate that it had involved a live SARS-CoV-2 virus sample or researchers working with one, which meant its relevance to the origins debate was entirely speculative. But the most implausible part of this story was that Reid had determined all this by parsing Communist Party dispatches he had downloaded from the WIV website. Why on earth would a regime notorious for its secrecy and control-freakery leave incriminating documents where Western journalists and analysts could obtain them at any time of their choosing?

As Reid explained it, the dispatches were written in “party speak”—“a secret language of Chinese officialdom”—which he was able to decode but which even native speakers of Mandarin could not be expected to understand. Almost as soon as the article was published, however, a more obvious explanation emerged when a number of Chinese speakers read the dispatches for themselves. As it turned out, they were able to understand them just fine and it was Reid who had made a mess of the translation. The supposedly incriminating passage about a biosafety emergency was in fact just political boilerplate about the willingness and readiness of loyal Party officials to meet the challenges of running a BSL-4 lab.

The discovery that the documents at the centre of the article’s most sensational claim were innocuous ought to have been fatal to Kao and Eban’s reporting (and certainly to their reliance on Reid as an authoritative source). On November 30th, ProPublica and Vanity Fair both amended their copy, and published a lengthy editorial response from ProPublica editor-in-chief Stephen Engelberg to the translation controversy, and to a list of other omissions and errors critics had subsequently identified. Engelberg and his team had consulted three other Chinese speakers and determined that Reid’s translation was at least plausible enough that ProPublica and Vanity Fair could be spared the embarrassment of having to retract the entire article. That didn’t change the fact that the substance of Reid’s allegation—that a biosafety crisis had occurred at the WIV in November 2019—was almost certainly incorrect.

VI. The Bioweapon Theory Returns

The Wuhan Institute [of Virology] was working on undeclared—under the biological weapons convention—classified work with the People’s Liberation Army on a programme that we saw as having no defensive orientation, okay? I can’t give you the facts as to why we felt it was more offence than defence. You’ll just have to trust me.

~State Department consultant David Asher, YouTube, May 2021

On June 10th, 2023, the Sunday Times published a startling investigation alleging that SARS-CoV-2 may have been the product of a secret Chinese biowarfare programme. DRASTIC researchers and sympathetic journalists had been careful to avoid making this claim since the lab-leak hypothesis had been popularised in mid-2021. Not only did it risk complicating their own concerns about the risks of approved engineering research, but it smacked of exactly the kind of geopolitical paranoia that had helped to stigmatise the lab-leak hypothesis in the first place. On the other hand, the existence of a clandestine programme within the WIV would resolve one of the more puzzling problems with the DRASTIC narrative: if SARS-CoV-2 was the result of legitimate research, why did nobody seem to know anything about it?

The Sunday Times attributed the bioweapon allegations to three unnamed US investigators involved in preparing a fact sheet about COVID origins for the State Department in the final days of the Trump administration. The fraught production of that document was subsequently detailed by Christopher Ford, the Trump administration’s Assistant Secretary of State for International Security and Nonproliferation and acting Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security. Among the officials tasked with preparing the fact sheet were Ford’s deputy Tom DiNanno and an Arms Control, Verification, and Compliance (AVC) Bureau consultant named David Asher.

In late 2020, Asher and DiNanno briefed Ford on the results of their intelligence review in advance of the fact sheet’s preparation. Their findings included the following:

- A statistical analysis prepared for the AVC by pathologist Steven Quay demonstrated that the likelihood of a lab leak was beyond reasonable doubt.

- The WIV had been messing around with a coronavirus named RaTG13, the closest relative to SARS-CoV-2, and this virus may have provided the backbone for the artificial creation of SARS-CoV-2.

- The involvement of People’s Liberation Army (PLA) officers in WIV research suggested that this work was likely undertaken as part of a covert bioweapons research programme. (Asher and Quay have since speculated that China’s vaccine research might be better understood as an attempt to develop a bioweapon “antidote.”)

- Intelligence indicated that several WIV workers had been hospitalised with COVID-consistent symptoms in the autumn of 2019, which suggested that those researchers might have been the pandemic’s patients zero.

Ford was alarmed by this briefing but also wary. If these claims were to be included in an official State Department document, he explained, they would have to be rigorously peer-reviewed. A month later, a review panel had still not been organised and Ford was dismayed to discover that DiNanno and Asher were briefing interagency colleagues about their suspicions instead. On January 4th, 2021, Ford emailed DiNanno and Asher requesting an urgent update. He reiterated the need to ensure that their allegations were watertight if the State Department was to take ownership of them, and he pointed out that the involvement of PLA officers in biolab work would not be sufficient to infer a bioweapons programme “since by that faulty logic we ourselves must have a BW program—which of course we don’t.”

In a testy email exchange with DiNanno during February 5th–6th, Ford’s frustration got the better of him:

If you’re right, you should be willing to prove it, and to confront experts who—unlike all of the people involved in building and making this argument for you—actually have training in the scientific field about which you make assertions. I really don’t know how I could possibly have been more clear about this over the course of the last month. Your allegations are dramatic, and potentially very significant indeed, but it’s for precisely that reason that they need to be tested and evaluated carefully.

Ford closed his email with two lengthy parentheticals:

(I will be brutally honest: after all that has happened, I’ve become worried enough about good faith here to need some reassurance that AVC will actually pick an objective panel. You guys have been quick to impugn the honesty of scientists who have disagreed with your conclusions, such as alleging conflicts of interest and claiming—although the syllogism is a logical fallacy—that because such arguable conflicts of interest allegedly exist those persons must therefore be lying. AVC now needs to live by the same standard you demand of others: you need to have a panel with sufficient third-party, objective integrity to protect you against being accused of deck-stacking.)

(For similar reasons, you also need to have some kind of appropriate IC [Intelligence Community] representation within the group, since Asher has made me very uneasy by repeatedly arguing against having intelligence analysts involved in assessing his arguments. Frankly that makes me suspicious, especially given his tendency to refer breezily to conclusions he says he has reached on the basis of reading “all” of the intelligence reporting—claims the truth of which the average listener, of course, has no particular way to assess. If he’s right, he shouldn’t be afraid to have someone else in the room who really has read “everything.”)

The peer-review panel was eventually convened on the evening of January 7th, 2021, and Asher and DiNanno’s claims did not survive scrutiny by the assembled scientists and IC analysts. In a lengthy summary of that discussion emailed to his State Department colleagues the following day, Ford reported that the panelists had been particularly unimpressed by the statistical claim:

[I]t appeared that this statistical analysis is crippled by the fact that we have essentially no data to support model inputs. Critically, we have no data on the amount of bat coronaviruses that exist in the wild—which is to say, we have very little of baseline information against which AVC’s analysis compares SARS-CoV-2. (At present, only perhaps 0.02 percent of such bat viruses, and perhaps 20 percent of bats though[t] to carry such coronaviruses have apparently been sampled, and there is enormous diversity in the bat virus population.)

The panelists pointed out that RaTG13 was not the closest relative to SARS-CoV-2, but “merely the closest known relative,” and that it could not possibly be the backbone used to create SARS-CoV-2. Furthermore, the claim that the WIV had “thousands of viruses” seemed to draw no distinction between live samples (which are difficult to extract in practice) and sequences derived from fragments of genetic material. Finally, on the “patients zero” allegation, the panelists cautioned that the confounding problem of asymptomatic spread and frequent travel back and forth between Wuhan and rural China (where spillovers may have already occurred but where disease surveillance was scant) made any hope of identifying a definitive index case remote.

Ford closed his summary by advising that the State Department should not accuse China of violating its commitments under the Biological Weapons Convention since there was no evidence it had done so. He repeated his concern that it would be “difficult to say that military involvement in classified virus research is intrinsically problematic since the U.S. Army has been deeply involved in virus research in the United States for many years.”

The 782-word State Department fact sheet that resulted from this quarrelsome process was probably the best that Ford could have hoped for, but it was still a tissue of vague and unsupported speculation. The rumour about the sick WIV researchers survived and would re-emerge in a series of media reports (including the ProPublica/Vanity Fair investigation) over the ensuing months, gathering new details with each subsequent iteration. Concerns about PLA involvement at the WIV and unspecified research involving RaTG13 also made it into the final draft in diluted form, which meant the import of this information rested on innuendo rather than on assertion.

If Christopher Ford had won a minor battle on behalf of State Department integrity, his opponents ended up winning the wider information war by appealing to the credulity of newspaper editors who lacked Ford’s scepticism or his concern with protecting the reputation of the institution for which he worked. The Sunday Times investigation represented the nadir of this process, in which journalism seemed to have been replaced by something closer to stenography. At the top of a remarkably restrained Twitter thread responding to the Sunday Times article’s many allegations, Florence Débarre described their investigation as “the most scientifically inept and journalistically shameful article on Covid origins I have read so far (the bar was high).”

No mention was made in the Times article of the misgivings expressed by the State Department’s panel of experts. The Mojiang mine, RaTG13, the DEFUSE grant proposal, the furin cleavage site, and the State Department cables were all disinterred for tendentious reinspection, but counterpoints were not acknowledged (still less addressed) and nobody with the relevant domain expertise seemed to have been approached for context or analysis or any kind of comment at all. Unsupported assertions, hearsay, and conjecture attributed to unnamed sources were all reprinted without any indication that the substance of these allegations had been subject to any editorial scrutiny or verification, even though the implications of these allegations were unambiguously grave.

“Having something that sounds scientific to say when making assertions to laymen is not the same thing as being correct,” Christopher Ford had advised Tom DiNanno. “I do not have the scientific expertise to critique David [Asher]’s claims. Nor do you. Nor, in fact, does he have actual technical training in the first place. That doesn’t necessarily mean he’s wrong, of course, but it does have implications for how to deal with the complex and controversial claims you guys are making about weedy bioscience.” Ford had the humility to grasp what he didn’t know and a stabilising commitment to the principle of verifiability. The fact-sheet investigators and the journalists they exploited apparently had neither.

Thirteen days after the Sunday Times investigation appeared, a long-awaited report from the US Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) was released pursuant to the terms of the 2023 COVID-19 Origin Act, which mandated the declassification of “any and all information relating to potential links between the Wuhan Institute of Virology and the origin” of the pandemic. The report was just 10 pages in length, fewer than four of which were devoted to substance. Nevertheless, it effectively reduced to rubble every intelligence-based claim about a link between the WIV and COVID-19 that had made its way into the media.

On the hypothesis that RaTG13 could have been turned into SARS-CoV-2:

In 2013, the WIV collected animal samples from which they identified the bat coronavirus RaTG13, which is 96.2 percent similar to the COVID-19 virus. By 2018, the WIV had sequenced almost all of RaTG13, which is the second closest known whole genome match to SARS-CoV-2, after [Laos coronavirus] BANAL-52, which is 96.8 percent similar. Neither of these viruses is close enough to SARS-CoV-2 to be a direct progenitor.

On the hypothesis that the SARS-CoV-2 furin cleavage site was artificially inserted:

We assess that some scientists at the WIV have genetically engineered coronaviruses using common laboratory practices. The IC has no information, however, indicating that any WIV genetic engineering work has involved SARS-CoV-2, a close progenitor, or a backbone virus that is closely related enough to have been the source of the pandemic.

On the allegations of a biosecurity crisis at the centre of the ProPublica/Vanity Fair exclusive:

We do not know of a specific biosafety incident at the WIV that spurred the pandemic and the WIV’s biosafety training appears routine, rather than an emergency response by China’s leadership.

On the allegation that three WIV workers had been hospitalised in late 2019 with COVID-consistent symptoms:

We have no indications that any of these researchers were hospitalized because of the symptoms consistent with COVID-19. One researcher may have been hospitalized in this timeframe for treatment of a non-respiratory medical condition.

On the WIV’s collaborative work with the PLA:

Information available to the IC indicates that some of the research conducted by the PLA and WIV included work with several viruses, including coronaviruses, but no known viruses that could plausibly be a progenitor of SARS-CoV-2.

On the bioweapon allegation:

All IC agencies assess that SARS-CoV-2 was not developed as a biological weapon.

And finally, the coup de grace:

We continue to have no indication that the WIV’s pre-pandemic research holdings included SARS-CoV-2 or a close progenitor, nor any direct evidence that a specific research-related incident occurred involving WIV personnel before the pandemic that could have caused the COVID pandemic.

Three and a half years after the pandemic began, neither the West’s most powerful news organisations nor the US intelligence community had been able to find anything to support claims of a lab accident in Wuhan. The lab-leak hypothesis was a bust.

Lab-leak theorists have stubbornly refused to accept this fact. On Twitter, David Asher joined other lab-leak theorists in alleging that the intelligence services were now participating in the cover-up. The more straightforward explanation for the failure of the ODNI investigation to uncover any evidence of a lab accident is that there was nothing to find. Absence of evidence is not necessarily evidence of absence. But if something really does not exist, the only evidence of that nonexistence will be a lack of evidence to the contrary. That is precisely why the burden is on those alleging a lab leak to provide proof of their allegations. Otherwise, what is asserted without evidence should be dismissed in the same way.

Some theorists seized on a single line in the ODNI report which allowed that, “All agencies continue to assess that both a natural and laboratory-associated origin remain plausible hypotheses to explain the first human infection.” But this is only true in a very narrow sense, and the existing balance of probabilities need not strand us in agnosticism.

VII. The Case for a Natural Origin of SARS-CoV-2

The clean-up of the Huanan market in the early hours of December 31st, 2019, may have been intended as a hasty containment measure, but it was a forensic calamity. Valuable information that might have helped investigators to establish what had happened at the market was immediately contaminated or lost. Vendors selling illegal wildlife had already vanished along with their goods, and the investigation was further disrupted by growing Chinese intransigence.

As the scale and gravity of the unfolding crisis became apparent, the CCP’s willingness to divulge information about the origins of the epidemic in Wuhan ground to a halt. By the time Chinese health authorities acknowledged that human-to-human transmission was occurring on January 20th, 2020, COVID-19 was no longer just a Chinese problem, it was a global health emergency. Fearful of liability and reprisal, the CCP began to impose strict controls on the publication and sharing of scientific data, and by March, authorities were already promoting the risible notion that the virus had not emerged in China at all.

All this made the task of understanding the earliest days of the pandemic extraordinarily difficult. Nevertheless, scientists have managed to amass an incomplete but compelling body of evidence supporting a natural origin of SARS-CoV-2, a review of which was published by Eddie Holmes et al. in Cell in August 2021. In sum:

- Striking similarities exist between SARS-CoV-2 and other known human coronaviruses, all of which had a zoonotic origin. For instance, “In direct parallel to SARS-CoV-2, HCoV-HKU1, which was first described in a large Chinese city (Shenzhen, Guangdong) in the winter of 2004, has an unknown animal origin, contains a furin cleavage site in its spike protein and was originally identified in a case of human pneumonia.”

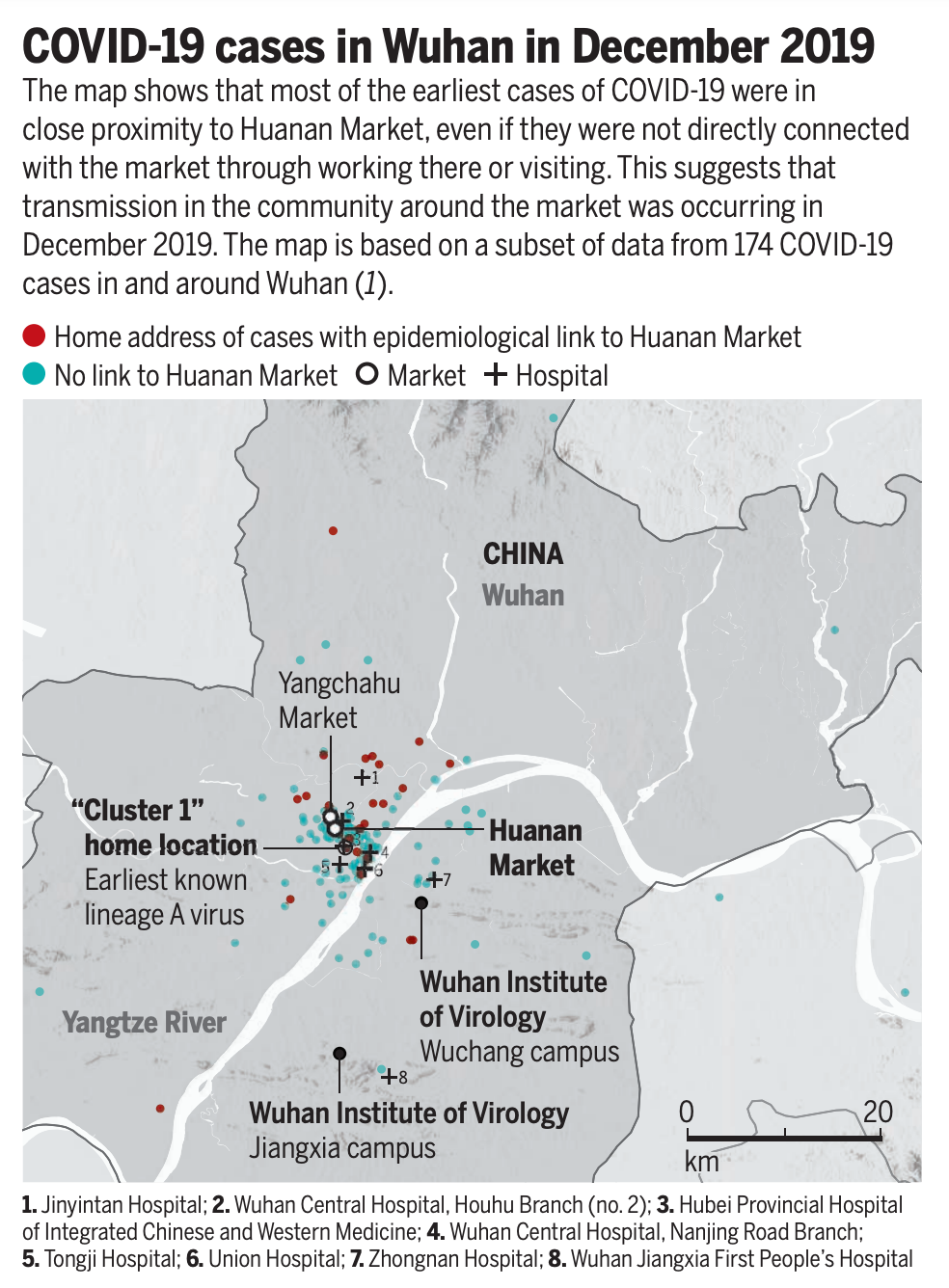

- Epidemiological data show that “55% of cases during December 2019 had an exposure to either the Huanan or other markets in Wuhan, with these cases more prevalent in the first half of that month.” Although the authors cautioned that early clustering around the Huanan market might be affected by sampling biases, they added, “These districts were also the first to exhibit excess pneumonia deaths in January 2020, a metric that is less susceptible to the potential biases associated with case reporting.” Asymptomatic spread might explain why some early cases had no epidemiological link to the market—the same was true of the early SARS outbreak in Foshan in November 2002.

- “SARS-CoV-2 was detected in environmental samples at the Huanan market, primarily in the western section that traded in wildlife and domestic animal products, as well as in associated drainage areas.”

- The earliest known mutation in SARS-CoV-2 split the virus into two lineages, A and B, “consistent with the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 involving one or more contacts with infected animals and/or traders, including multiple spill-over events, as potentially infected or susceptible animals were moved into or between Wuhan markets via shared supply chains and sold for human consumption.”

- “Viruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2 have been documented in bats and pangolins in multiple localities in South-East Asia, including in China, Thailand, Cambodia, and Japan.”

- The authors acknowledged that, “No bat reservoir or intermediate animal host for SARS-CoV-2 has been identified to date,” but they cautioned that this is likely due to undersampling or low prevalence. It is also not unusual. “The animal origins of many well-known human pathogens,” they noted, “including Ebola virus, hepatitis C virus, poliovirus, and the coronaviruses HCoV-HKU1 and HCoV-NL63, are yet to be identified.”

- Finally, the authors concurred with Andersen et al.’s conclusion in the March 2020 “Proximal Origin” review that nothing about the SARS-CoV-2 genome is inconsistent with a natural origin.

On July 26th, 2022, Science published two related papers that expanded on Holmes et al.’s conclusions. Worobey et al. looked more closely at the early case data in Wuhan and reconstructed a map of the market in an attempt to show where the environmental samples of SARS-CoV-2 were clustered. Pekar et al. examined the genomic diversity of the virus in the early days of the pandemic and concluded that lineages A and B “were the result of at least two separate cross-species transmission events into humans.”

This passage from the Worobey paper is particularly interesting:

One of the key findings of our study is that “unlinked” early COVID-19 patients, i.e., those who did not work at the market, did not know someone who did, and had not recently visited the market, resided significantly closer to the market than patients with a direct link to it. The observation that a substantial proportion of early cases had no known epidemiological link had previously been used as an argument against the Huanan market being the epicenter of the pandemic. However, this group of cases resided significantly closer to the market than those who worked there, indicating that they had been exposed to the virus at or near the Huanan market.

The early epidemiological data clearly show linked and unlinked cases clustered around the market, radiating outwards across the Yangtze River towards the Wuhan Institute of Virology, rather than the reverse:

Each of these lines of evidence—precedence; the early epidemiological, mortality, and seroprevalence data; the virus’s phylogeny; the indications of multiple spillovers; the genetic consistency with zoonotic relatives described before the pandemic and since—has its weaknesses. This was to be expected, even without the vandalism of the market data by the Wuhan clean-up operation. It is rare for any single piece of evidence to be decisive, which is why investigators will look for convergence, especially when relevant information has been compromised or destroyed. And if evidence starts to converge on one answer, that is a pretty reliable indication that you are looking in the right place.

Here, multiple mutually reinforcing kinds of data all fit together to create a coherent picture of a zoonotic event with the Huanan market at its centre. Some of these data may be stronger than others, but the possibility that they are all wrong—and so completely wrong that they can be disregarded entirely—is vanishingly remote. The most parsimonious explanation for this convergence is that it is exactly what it looks like and exactly what we would expect to see had a spillover occurred in the market.

The failure to uncover a similar convergence on any alternative possible hypothesis explains lab-leak theorists’ inability to settle on a coherent narrative of their own. They remain unclear about whether Chinese scientists sampled SARS-CoV-2 or its progenitor, since there is no evidence to suggest either. Assuming the latter, they have not decided whether SARS-CoV-2 was created using genetic engineering or serial passage in culture or both. They are not even positive about which lab in Wuhan the virus is supposed to have escaped from. And amazingly, the mutual exclusivity of these possibilities has never particularly bothered them.

“I feel validated,” Alina Chan announced in March 2023 when the US Department of Energy decided that the pandemic was probably caused by a lab accident. “Not because they lean toward the exact same lab leak scenario as me but because they weren't suckered by the double spillover market hypothesis.” The DoE believed that SARS-CoV-2 may have leaked from the Wuhan CDC, which is a lot closer to the market than the WIV but does not conduct bioengineering experiments. But Chan had spent most of her book casting suspicion on the experimental work carried out by WIV scientists and their US collaborators.

This is like reading an investigative account of JFK’s assassination that blames his murder on the mob, only to watch its author stand to applaud a government report blaming the CIA because at least the report’s authors hadn’t been suckered by the Warren Commission. The COVID-origins question only has one right answer, and if Chan believes the virus escaped from the WIV, then the theory that it escaped from the Wuhan CDC must be as wrong as the theory that it spilled into humans at the Huanan market. I’m left to wonder what Chan actually believes. If she’s not clear in her own mind, it’s because no evidence provides her with a good reason to prefer one lab-leak hypothesis over another.

Had the outbreak actually begun at the WIV, at least some incriminating evidence would have converged on that conclusion by now, even if that evidence was scanty and imperfect. Not only is there no evidence of an outbreak at the Institute or an epidemiological link there, but it has continued its operations uninterrupted and Shi Zhengli remains at her post to this day. This is an unthinkable state of affairs if the CCP knew that her lab was responsible for the pandemic. Shi certainly would not have been allowed to casually tell Scientific American in March 2020 that she had lost sleep over the possibility of a lab leak until she was able to disconfirm it.

The convergence of evidence favouring a natural spillover poses a problem for lab-leak theorists. Not only must they come up with countervailing evidence that implicates a lab and (at least) one of its researchers, but any resulting hypothesis must also make sense of the existing evidence favouring a market emergence. I no longer believe that is possible, and I don’t think the lab-leak theorists think it is possible either. Which is why, instead of trying to accommodate the emerging data into a lab-centred explanation, they have sought to discredit it in two ways.

First, they have simply ignored the powerful implications of convergence and attacked the weaknesses of each piece of evidence in isolation. This technique has kicked up a great deal of dust and managed to convince a lot of people that the cumulative case for a natural origin is less robust than it actually is. Second, they have attempted to discredit the source of the information by attacking the professional and personal integrity of the scientists investigating COVID-19’s origins. In the absence of any evidence supporting their hypothesis, theorists have tried to build their case backwards, attempting to prove a cover-up before they have established that there is anything to conceal.

This campaign has been unrelenting since the publication of the “Proximal Origin” paper in early 2020, and it has only increased in venomous intensity since the publication of the 2023 ODNI report. Virologists and evolutionary biologists are routinely vilified as liars and frauds, who employ a veneer of scientific authority to cover up their own complicity in millions of deaths. If these scientists can be convincingly portrayed as so corrupted by conflicts of interest that nothing they have to say on the topic can be trusted, then not only can all the evidence they produce be disregarded, but so can any objections they may raise about the scientific illiteracy of lab-leak claims.

This explains the use of Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to obtain the private correspondence of public-health officials, which is then pored over in search of something—anything—suspicious or embarrassing. I will admit to feeling ambivalent about this approach. As a journalist, I favour disclosure, and as an individual, I am naturally curious to see how public figures discuss consequential scientific matters behind closed doors. On the other hand, this situation makes candid discussion between colleagues almost impossible. In private, we can communicate in shorthand, confident that our intended meaning will be correctly inferred by those who share our frame of reference. Public messaging, on the other hand, requires great care to minimise the risk that words will be misunderstood or misused. This is particularly critical during a crisis, for reasons that ought to be self-evident.

It is entirely unsurprising to me that an NIH official advised correspondents in one of the emails disclosed by the Intercept that, “I try to communicate on gmail because my NIH email is FOIA’d constantly.” It is simply inevitable that anyone in that position would start to think this way. Not just because they want to speak freely, but because they know that if their remarks end up in the New York Times, they will be seized upon and refashioned into a cudgel. Lab-leak theorists are perfectly capable of grasping this, but they are so preoccupied with the task of destroying their opponents that they never make a good-faith effort to understand them.

Nowhere has this been more evident than in the recent disclosure of the Slack-channel archive with which I opened this essay. The flagrant misrepresentations of those Slack discussions are emblematic of lab-leak theorists’ approach to scientific inquiry. In an effort to prove mendacity at every turn, each decision, judgement call, and statement is subjected to the most uncharitable and sinister interpretation available, even when a charitable or innocuous alternative will do just as well or better. Apparent anomalies, discrepancies, and contradictions are all treated in the same way—the possibility of human error, faulty memory, mitigating context, happenstance, or coincidence is dismissed a priori, and everything becomes grist to a narrative mill of institutional malfeasance and corruption.

This behaviour consumes an inordinate amount of lab-leakers’ time and energy, even though it does nothing to advance the argument about COVID-19 origins in any useful direction. The unending row about whether or not Andersen et al. prematurely dismissed the possibility of a lab-leak in their March 2020 “Proximal Origin” review, and whether or not that public document properly reflected its authors’ private doubts, tends to obscure two facts. First, that the authors’ conclusions have dated remarkably well. But second, even if they had got everything wrong, nothing in their paper or the disclosed emails and Slack chats can possibly prove or disprove a lab origin, which is what this entire debate is supposed to be about.

As Stuart Neil pointed out in June 2021 during the RaTG13 debates, the entire lab-leak hypothesis rests on the assumption that the WIV had either SARS-CoV-2 or its progenitor in its freezers on the eve of the pandemic. “If they didn’t have it, WIV cannot be the origin of SARS CoV-2 no matter what else they were doing, what containment they used, or what KGA wrote in an email.”

VIII. The Trap

In February of this year, a minor spat occurred in an anti-ivermectin corner of the Internet. Contrary to claims made by the drug’s advocates, psychiatrist Scott Alexander suspected that ivermectin was probably not an effective treatment for COVID-19 and that the studies indicating otherwise were likely junk. So, he published a 10,000-word review of the ivermectin literature in order to test (and possibly confirm) that hunch. An ivermectin advocate responded with a lengthy rejoinder, so Alexander wrote a 15,000-word response to that response, in which he conceded a point or two, but overall reaffirmed his view that ivermectin is not a reliable treatment for COVID-19.

Chris Kavanagh—a podcaster who shares Alexander’s ivermectin-scepticism—responded with a Twitter thread in which he mocked Alexander for wasting his time refuting a conspiracy theory at such length. This kind of approach, Kavanagh explained, is “indulgent & potentially misleading as it leans into the framing of this being a legitimate area of scientific controversy when it is much more akin to debating with 9/11 truthers.” This is a familiar argument—that a serious response to conspiracists risks conferring undue legitimacy upon people better dismissed and marginalised as ignorant and destructive cranks.

In the first of two responses to Kavanagh, Alexander explained why he finds this approach unsatisfactory. He began by revealing that, as a teenager, he had been an Atlantis conspiracist for a while, and that he was not about to be talked out of that mistake by people calling him an idiot. He needed a methodical argument explaining why his beliefs were wrong. It doesn’t matter that not everyone will be convinced by or even receptive to such an argument—it should be available to those who are ready for it. Calling conspiracy theories stupid in an attempt to stigmatise them as low-status is more likely than not to provoke perverse obstinacy.

I am entirely with Alexander on this, which is why this essay exists and why it runs to such inordinate length. I misspent much of my youth believing that JFK was assassinated by a conspiracy of some kind, and it wasn’t until I was ambushed by a documentary carefully explaining why I was wrong that I managed to think my way out of it. I then spent hours on John McAdams’s dedicated website looking up all the arguments I’d found most compelling in the conspiracy books I’d read and devouring McAdams’s rebuttals. Finally, I read Gerald Posner’s excellent book about the assassination, Case Closed.

I learned almost nothing of value when I was a conspiracy theorist, but I did learn quite a lot pulling myself out of that mindset, and like Alexander, I would never have done so had I only ever encountered people who told me I was being an imbecile. Part of the appeal of conspiracy theories is that they allow a person to feel more intelligent than the drones who passively drift along on the current of received consensus.

This is why the February 2020 Lancet statement organised by EcoHealth Alliance president Peter Daszak was such an unfortunate error. A careful refutation of the false claims then circulating might have been valuable and worthwhile. Instead, the statement’s authors threw a fistful of links at sceptical readers and then moved swiftly into the language of condemnation and exhortation, invoking the ex cathedra authority of scientific opinion and the stigma of conspiracism in an attempt to shame opponents into mortified silence. This only further irritated and galvanised those it was meant to embarrass. And when Nicholas Wade effected a sea-change in elite opinion, the effort to suppress the lab-leak hypothesis became prima facie evidence of precisely what the Lancet statement was intended to dispel.

The failure of some of the statement’s signatories to disclose potentially confounding interests had only deepened consternation and suspicion among those they attacked. Daszak had dispersed grant money from the US National Institutes of Health to the WIV for coronavirus research. Was it a surprise that he would dismiss a theory of research malpractice in a lab that his organisation had helped to finance? The EHA’s connection to WIV research was hardly a secret, but in the minds of Daszak’s critics, that only made the declaration of “no competing interests” more brazen and galling. It added to the perception that scientists were not being entirely forthcoming about their own interests and biases. In this way, the Lancet statement became a handicap for the scientific side of the debate from which it has never fully recovered.

But the authors were correct, nonetheless, to worry about the lab-leak hypothesis and the implications of the conspiratorial mindset it represented. I have sometimes wondered if my own experience with conspiracy thinking equipped me to resist its pull. I suspect it did not. I was just fortunate to have read Philippe Lemoine’s careful investigation into the matter before the lab-leak idea surged into mainstream acceptability. Without that protection, and without making the time to dive into the topic and figure it out for myself, I would probably have allowed myself to be swept along in the tide with just about every other writer and public intellectual I respected in the heterodox mediasphere.