Books

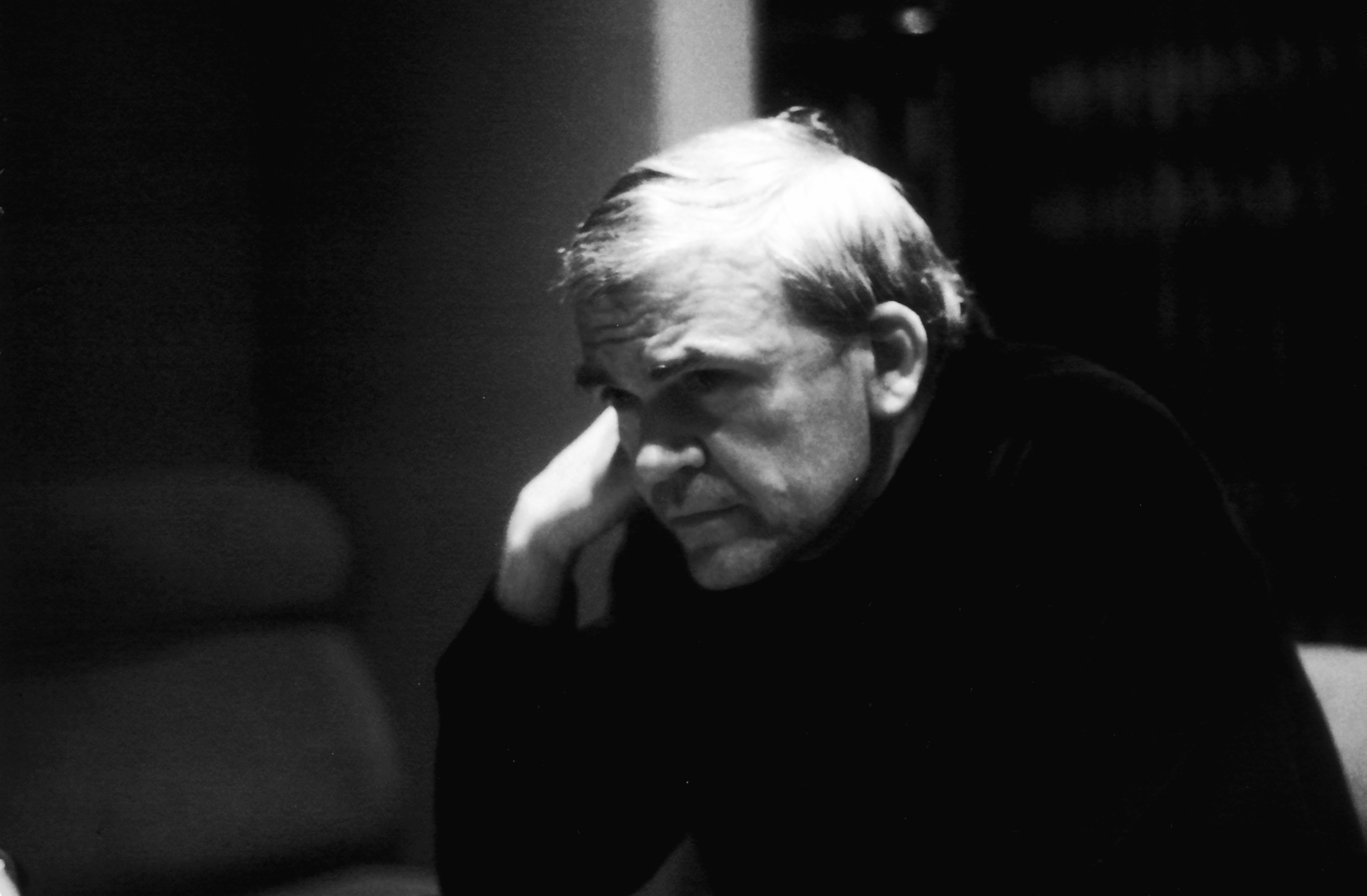

Milan Kundera: The Nobel Prize for Literature Winner We Never Had

Few writers in our time were more committed to the novel or had more idealism about the heights the form could scale.

For a long time before his death this week at the age of 94, the novelist Milan Kundera seemed to have fallen out of fashion with critics. Jonathan Coe wrote of his “problematic sexual politics” with their “ripples of disquiet.” Alex Preston complained about the “adolescent and posturing” flavour of the books which had thrilled him in his youth, adding of Kundera’s later novels that reading them was an “increasingly laboured process of digging out the occasional gems from the abstraction and tub-thumping philosophising… a series of retreats into mere cleverness.” Diane Johnson of the New York Times seemed to ring the death knell loudest: “what he has to tell us seems to have less relevance… the world has run beyond some of the concerns that still preoccupy him.”

Doubtless Kundera’s light had dimmed in the last few decades. No substantial novel had come from him since Immortality (1990), just before he switched from writing in Czech to French. Yet these critics’ withdrawal of support seemed modish, ironic, and not without schadenfreude. Preston and Johnson were hardly household names, and Jonathan Coe, though a sharp enough satirist, scarcely his Swiftian namesake. Yet you get the sense that Kundera, whose novels for so long were required reading for anyone drawn to world literature, was being pushed firmly to the margins. Some of it surely was his writing on sex, which since the #MeToo movement was jarringly out of fashion. Kundera was avid about it in ways that, to the squeamish, now seemed less ground-breaking than a bit creepy, with lip-smacking descriptions of the female body and sundry deviant sex acts. But sex—which we’re no longer supposed to think or care about—represented a fraction of his themes and was arguably a legacy of the communist period, one of the few ways individuals could assert their liberty in a repressive state.

Perhaps there was another reason: the 2008 “revelation” he’d once cooperated with the Czech secret police and put another man in jeopardy? Kundera emphatically denied the charge and even if it was true, plenty of his contemporaries had behaved the same way. “Every now and again,” he wrote, “history exposes humans to certain pressures and traps which nobody can resist.” He himself had never claimed any kind of moral purity. His books are stuffed with explorations of betrayal and moral greyness. It wasn’t as if a saint had fallen off Charles Bridge.

No, it seemed just as possible Kundera had become a teller of truths inconvenient to the modern age, that his ruthless analysis of male-female relationships, his omniscient male voice and his dissection of sheep-like political movements were simply too close to the bone. More than almost any other writer, he seemed in his early work to foresee our own times: an atmosphere of growing intolerance and Rhinoceros-like groupthink that increasingly resembles the Soviet world we thought we’d left behind.

Few writers in our time were more committed to the novel or had more idealism about the heights the form could scale. “The novel’s spirit is the spirit of complexity,” he wrote. “Every novel says to the reader: ‘Things are not as simple as you think.’” Each was a “paradise of individuals,” a world in which all characters had their reasons. No one could be right or wrong, and all could expect to be understood—anathema to any movement wanting heroes, villains, or easy answers. The complexity of a proper novel, he argued, was part of its appeal. Understanding it took time, effort and dedication. No novel could be read, only reread, till a reader discerned the “web of ironic connections” beneath the surface. Interviewers pressing Kundera on his loyalties found him just as difficult to pin down. Was he on the Left? “I’m a novelist.” On the Right then? “I’m a novelist.” At times his dedication to the form reached an obsessiveness that was either impressive or just plain cranky. He sacked a publisher for changing his colons to full stops forbade stage versions of his books and issued a ban on Kindle editions. To date all must be read in hard copy, or not at all.

This sense of vocation was ironic, for Kundera originally trained as a composer, and there’s something noticeably symphonic about his books. Each is in seven parts, with sections corresponding to adagio, allegro, prestissimo, and so on. In The Joke (1967) Kundera told the story of a young communist expelled from the Party for a misjudged witticism. Life is Elsewhere (1973) was about the development of a young, mother-fixated poet and his subsequent move into left-wing student politics. In The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984)—his breakthrough novel in the West—Kundera gave us the story of a surgeon and his two contrasting lovers, set against the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. All these books had the same mix of politics, psychology, history, philosophy, and sex. In the hands of another writer—more conventional—the recipe could have proved indigestible, but with Kundera there’s an airiness about it all. Everything’s stripped down to its essence and given space to breathe. We rarely find out what his protagonists look like, what homes they inhabit, or what they eat and drink. Instead, it’s each character’s existential situation that defines them. Kundera dreamt up Tomas (his Prague surgeon in Unbearable Lightness, caught between two women) from a single image: a man staring out of the window and balancing on a knife edge between freedom and responsibility, wondering which way to jump. There’s no suggestion his characters are real, that they’ve sprung from anything but the author’s fantasy, which he allows full play. Kundera’s magic realism was the most accessible kind—never too magical, never too stodgily realistic, and always seeming to be about our own lives.

Domestic details aside, Kundera wrote about nearly everything: memory and forgetting, dogs, state executions, cactuses, peace marches, nakedness, indigestion, the politics of love, the politics of betrayal, the battle between the soul—which longs to fly—and the body, stubbornly earthbound, which belches, rumbles, and sniggers at it. Of his beloved Rabelais, Kundera said what thrilled him about this writer and similar novelists was “they talk about what fascinates them and they stop when the fascination stops.” Ditto, Kundera.

What he described brilliantly—a dire warning for the Woke Era—was the feeling of an alien ideology flying in and spreading like a bushfire from weak mind to weak mind, from one institution to another. By the time he was 40 Kundera had lived through the Nazis’ occupation of his country, its later surrender to Stalinism, the liberalisations of the Prague Spring and the Soviet clampdown that followed. He knew the XYZ of living under power—and the absurd black comedy it could sometimes be. With the cult of the noble worker under communism, middle class Czechs started to lose their heads, to think other people’s thoughts and speak in slogans. In one story, a woman cusses her partner for making love to her “like an intellectual.” Another woman, with inverted bourgeois snobbery typical of the times, rhapsodises about the “authenticity” of proletarian cafes and avoids good restaurants altogether. (She finds her counterpart in today’s “woke” Caucasian, bleating inanely that an event they’ve been to was “so white.”) Kundera pinpoints it all in a way that rings bells: the dippy idealism, the earnest smiles, the suffocating scout-camp atmosphere of healthiness, and the pitiless absence of irony or satire. There’s the mob-persecution, too, of individuals not swept up by the madness. “Anyone who failed to rejoice,” he wrote, “was immediately suspected of lamenting the victory of the working class or (what was equally sinful) giving way individualistically to inner sorrows.” In recent times, missteps with orthodoxy have meant job-loss and “cancellation.” In Kundera’s, they often spelt death.

A short story in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (1979)—probably his signature work—imagines a group of the communist faithful dancing in a circle—so joyously they levitate over the Prague rooftops as dissenters and ex-communicants are vaporised below. The early Communist period in Prague—apart from its atmosphere of giddy, utopian psychosis—was marked by horrors, many of them surreal. There was the fatal defenestration (or suicide?) of Jan Masaryk, son of the former president, who went along with the new regime and realised too late his monstrous error. Czech critic Záviš Kalandra was hanged while his friend poet Paul Éluard came out in shameless support of his murderers. In 1952, in the show-trials and purges of the government, communism’s brightest and best were framed, executed, and incinerated, their ashes scattered on a Czech highway. And through all of this, Kundera’s dancers keep up their joyous quickstep, jigging with double fervour as those outside the circle are ground into crematorium-dust. They’re on the right side of history, and their hearts are pure. Kundera calls them “the angels,” and he both loathes and envies their callous sense of belonging, of moving in step with the times.

They’re also mostly young, and thrilled that their new found emancipation has happened so close to the wheel of history. They can denounce, sack, and ostracise whoever they like, even (perhaps especially) their elders. Life is Elsewhere features an effete young poet suddenly empowered by the collective, gleefully telling a former mentor that he and those like him are to be swept “into the dustbin of history.” If the phrase is someone else’s—purloined from Trotsky—that’s no accident either. “The young can’t help playacting,” wrote Kundera . “They are thrust by life into a complicated world where they are compelled to act fully grown. They therefore adopt forms, patterns, models—those that are in fashion, that suit, that please—and enact them.” So many events in our own time spring to mind: Oxford’s “Rhodes Must Fall” campaign, the violent picketing of Brett Weinstein at Evergreen State College, the absurd list of Halloween costume bans at Kent University. “Youth is terrible,” Kundera writes. “It is a stage trod by children in buskins and a variety of costumes mouthing speeches they’ve memorized and fanatically believe but only half understand… easily roused mobs of children whose simulated passions and simplistic poses suddenly metamorphose into a catastrophically real reality.”

In his first novel The Joke, Kundera showed what that catastrophe meant for anyone going against the herd. The book is a long meditation on the state of being cast out. A young communist called Ludvik—one of Kundera’s dedicated ironists—jots down a few political wisecracks on a postcard and sends it to the wrong woman. He’s accordingly denounced, kicked out of university, expelled from the Party, and sent off to do hard labour in the mines. In a central scene in which his peers and friends all raise their hands against him, wanting—then as now—a grovelling apology, in which he’ll confess his sins and outdo his detractors in self-accusation. He throws himself at their mercy, but it changes nothing.

Hardly a unique story—one repeated weekly in our times—but what makes it definitive is Kundera’s exploration of the young man’s inner state and what pariah-hood like this does to the victim. Ludvik ends up siding genuinely with his attackers, internalises their accusations, becomes split from his own identity, and loses—forever—his faith in those around him. He’s now public property, part of a bigger narrative, and becomes unrecognisable to himself: “I came to realise that there was no power capable of changing the image of my person lodged somewhere in the supreme court of human destinies; that this image (even though it bore no resemblance to mine) was much more real than my actual self: that I was its shadow not it mine.” Totalitarianism means losing perspective, a frame of reference through which to survive: “I couldn’t imagine that everyone else might be wrong, that the Revolution itself, the spirit of the times, might be wrong, and that I, an individual might be right.” [My italics.] They’re words to be heeded nowadays by anyone trashed on social media, hounded out of their jobs, Twitter-stormed or “cancelled.” It has all happened before, and with much higher stakes.

Of course, it’s a joke Ludvik’s denounced for, and the novel makes clear how threatening humour is to those in power and how perilous, given the wrong atmosphere, it is to the joker, too. Quoted outside the stream of playfulness, the game in which it originated, a joke can appear obscene, even wicked. (One remembers the 2018 trial of Count Dankula for teaching a Nazi gesture to a pug, and the judge’s chilling comment that “context and intent are irrelevant.”) Fundamentalism, Kundera knew, was incompatible with humour—the latter an alternative reality with rules of its own, which trivialised the earnestness of ideologues and laughed them away to nothing. Humour wasn’t just a series of jokes, it was a philosophical system that “shone its light over everything,” and for this very reason, its practitioners had to be taken down. Offenders routinely got 10-year sentences under Stalin and in the process an entire redemptive area of life was denied existence. Yet this, Kundera felt, was just when the trait shone most brilliantly—a “wager,” a genuine risk, and a sign of character. In a 1980 interview with Philip Roth, Kundera said that he could always recognise a “non-Stalinist, a person I needn’t fear, by the way he smiled. A sense of humour was a trustworthy sign of recognition. Ever since, I have been terrified by a world that is losing its sense of humour.”

But in a world where to joke was to risk everything, and repeating the hoariest of political platitudes with a straight face was mandatory, what was left? Silence, perhaps, another of Kundera’s perennial themes. The spiritual aristocrats of his books are always the most private—like the delicious Sabina in Unbearable Lightness, his kitsch-averse artist who can’t bear to have a love affair made public, feeling it will lose all reality in the process: “…instead of being Sabina, she would have to act the role of Sabina, decide how best to act the role. Once her love had been publicised, it would gain weight, become a burden. Sabina cringed at the very thought of it.” Then there’s Tamina in Laughter and Forgetting, another of this author’s lovely reticents, who keeps a diary she’s terrified of anyone reading. The “gaze of those outsiders,” she reflects, would be “like rain obliterating inscriptions on walls. Or like light falling too soon on photographic paper… the intimate tie binding her to them would be cut.” Dignity, for Kundera, seemed to come from secrecy, from embracing your separateness, from not wanting to live through the eyes of others. Yet silence, in post-war Eastern Europe, was no longer an option either. In the hearty atmosphere of the times the refusal to join was viewed as a protest of its own (The BLM-associated phrase ‘Silence is Violence, from 2020,

springs conveniently to mind). At some point power—in phase two—will not simply leave you in peace. “Whoever is not with us, is against us.” It demands self-betrayal.

Yet Kundera knew that people were lining up to betray themselves in the modern age and needed little encouragement to raise the veil on their mysteries. Contrasted with Tamina’s shyness in Laughter and Forgetting is her friend Bibi, a curiously modern type who has no visible interest in literature but longs to write a book of her own: “I want to express my life and feelings, which I know are absolutely original.” Bibi hasn’t much interest in Tamina either but is drawn to her because Tamina listens more than she speaks and does not interrupt. She provides Bibi with an audience.

Soon, Tamina starts to dream at night about the ostriches, a gaggle of birds who follow her round clacking their beaks with an urgency that suggests they have something to tell her. Is she in danger? Are they issuing a warning? Do they have some urgent truth to impart? Finally Kundera tells us: “They are not at all concerned with her. They came, each one of them, to tell her about themselves. About how they ate, how they slept… About how their important orgasm had lasted six hours… About how they had been young, ridden bicycles, and eaten a sack of grass that day… There they are, standing face to face with Tamina, telling her their stories, all at the same time, belligerently, pressingly, aggressively, because there is nothing more important than what they want to tell her.”

His words anticipate our own cacophony of tweets, Facebook feeds, and Instagram posts by about 30 years.

“When everyone wakes up as a writer,” Kundera says in the same story, “the age of universal deafness will have arrived,” and throughout nearly all his work there’s a note of elegy. It’s for a world of meaning wrecked by heedless clutter, of silence and its accompanying revelations, destroyed by a din of cheap music. It’s a lament for the novel, a protest against a world grown deaf to ambiguity, whose governing orientation is towards childishness and flat, fairy-tale answers. “The end is not an apocalyptic explosion,” he wrote of literature’s decline. “There may be nothing so quiet as the end.”

How should one remember Kundera, now that his own end, after 90 years of history, has arrived? As a supreme anatomist of power? For his irony and playfulness, his cynical—though never unromantic—dissections of love? The strange sparse music of his books, his hatred of kitsch, his demonic delight in outraging our delusions? Will he be remembered at all, other than as a period piece? In a time of competing fundamentalisms—religious and political—it seems unlikely his posthumous reputation will have an easy ride, though as long as political or personal lies exist his work will have things to tell us. “The struggle against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting,” he famously wrote, and amnesia, it’s clear, is never out of fashion. The dream of communism—with its pat denial of human nature and its insistence that “real communism has never been tried”—refuses to disappear, whatever the car-crash with reality which invariably follows. In the world of Kundera’s books, there’s no divine justice and no crime’s ever properly redressed. Things merely fade over time, the world moves on, and people are never brutal enough with themselves to learn the lessons of experience. “History is as light as individual human life,” he wrote, “unbearably light, light as a feather, as dust swirling into the air, as whatever will no longer exist tomorrow.” Should the same prove true of Kundera’s novels—more pertinent than ever as today’s clutch of dogmas press their shrill, mirthless suits for our surrender—then the joke, not a very funny one, will be on us.

Editor's note: An earlier version of this article was published on 12 July, 2023.