Lost in Transition

The popularity of Harry Potter reveals a yearning for rites of passage that no longer exist.

Once faith waned in the existence of a higher divinity guiding human affairs, as it has for most who inhabit the modern world, the central metaphysical questions rise to the fore. These are the questions of where we have come from, what we should do with our lives in order to make sense of them, and what happens when we die, if anything. The discontents of our time lie squarely in the domain of life-meaning—or rather, in a feared lack of it.

The toll on teenagers will be heavy if their society does not provide them with secure entry to adulthood. At issue is belief, training, and morale. Accordingly, the principal rite of social passage is that from child to adult—Plato put it that the most important body in a society is the one that teaches the teachers.

This key rite of passage was dramatized in Australian Aboriginal culture with boys being subjected to an initiation ordeal on reaching puberty. The elders took the boys away from their mothers and subjected them to months of physical torture, which at the extreme might include tooth removal and subincision of the penis down to the urethral canal with stone tools. In the opening stages, the boys were told they were nobodies, worth nothing, smeared in ash, humiliated, as their child selves were obliterated. Then they were slowly introduced into the secret rituals and beliefs of the clan, taught the religious obligations of being an adult. This was a true death and rebirth ritual, and brilliantly successful. It was said initiation awakened the boys to the Law. That is, it educated them in their culture, and taught how to act as its custodians. It would mean they would spend their adult lives with their deepest pleasure the preserving of religious belief and ceremony.

Our modern Western initiation equivalent has, needless to say, been less dramatic and it has proceeded over many years in small stages. Its elements include leaving a cosy home aged five to enter an impersonal school; being taught over a dozen years skills for adulthood, self-discipline, and a capacity for systematic work; then leaving school, with its imposed order and discipline, to enter the vast, often seemingly anarchic, and intimidating adult world for work or tertiary education; turning 18 and being able to vote, getting a driver’s licence, meeting friends at pubs; exploring romantic liaisons; and getting married with the marriage service itself full of rite-of-passage symbolism, such as the Buck’s Party in which the youth has his last fling as an irresponsible member of the male horde, before entering the door of adulthood. There may have been wayward phases in character development such as Shakespeare charted in King Henry V, establishing the archetype of wise maturity achieved after a wild youth pitched into worldly experience among low-life scoundrels.

All being well, teenagers will enter adulthood with the optimism and confidence to take on the world and its challenges, to forge a life-path. But for that, children need exemplars, starting with parents, which means parents who are dynamically engaged in family, work, and leisure, parents who believe there is purpose to who they are and what they do. The Harry Potter books contrast the alternative to the magical world as ordinary humans, who are derisively satirised as Muggles—diminutive mugs or fools, prosaic, unimaginative, and condemned to a humdrum and boring existence. Their lives are hardly worth living. They stand as a cautionary threat to all child readers of what threatens them when they reach adulthood.

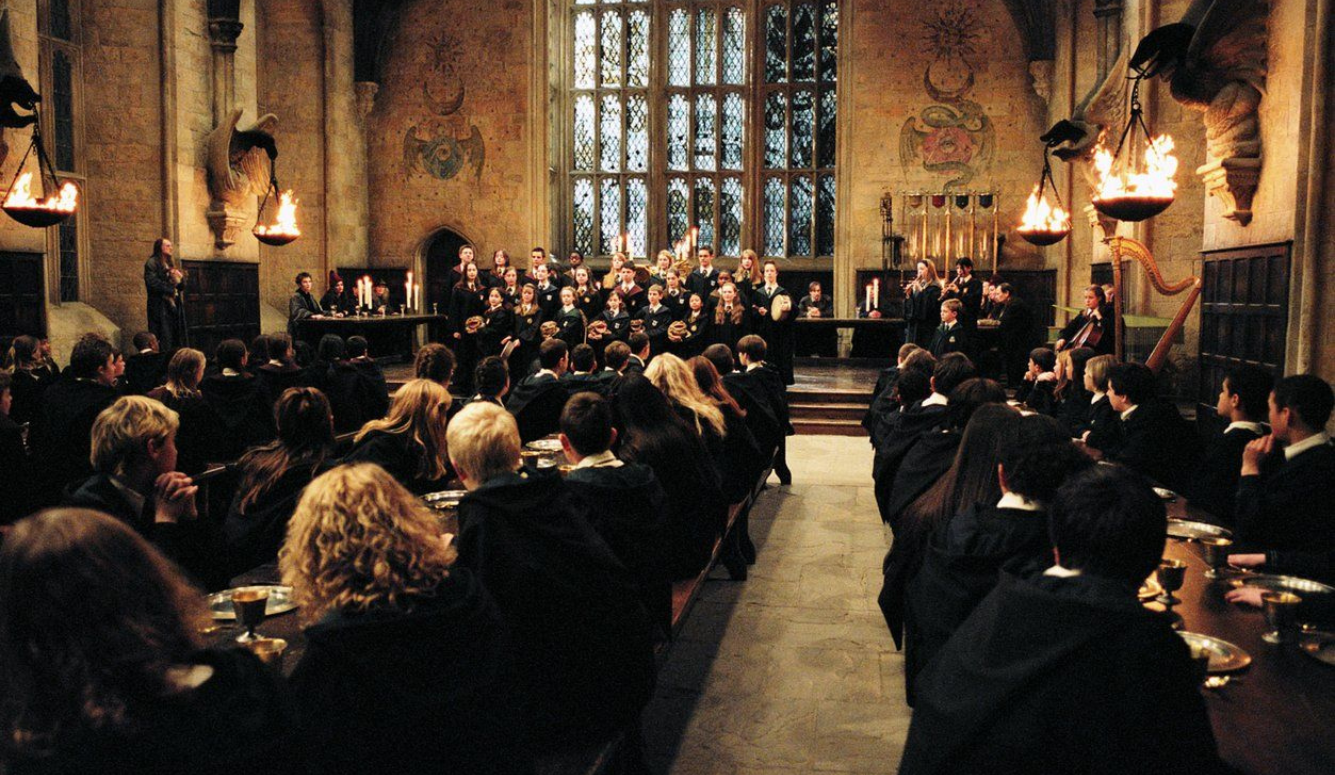

In Harry Potter there are admirable adults to provide the teenage students with role-models to identify with and want to be like—from the headmaster and some teachers, Harry’s godfather, to the gamekeeper giant, Hagrid. Paradoxically, this story, when examined carefully, is pervaded by untimeliness. Its physical setting seems deliberately and nostalgically anti-modern, even reactionary—a remote Victorian English boarding school, set in a castle, in which staff and students wearing academic robes feast together in a Great Hall with a High Table, and gather together in studies, common rooms, and dormitories. This is hardly modish.

Virtually all the major Harry Potter themes and implied messages clash with the claimed mainstream beliefs and attachments of the age in which it was created, and to which it speaks. That age has been confident, even arrogant in its proclamation of the freedom of individuals, the supremacy of their right to live as they wish, taking any pleasure they may, holding to be true whatever they choose, while being largely dismissive of universal laws and truths. The picture it leaves is the opposite of the cloud-cuckoo-land dream that life was meant to be easy, a condition of perpetual, untroubled leisure; that humans are all inherently good; and that insecure identity, neurosis, disappointment, and chronic free-floating anxiety may all be wished away. Harry’s life is a constant, unremitting ordeal.

In that children love J. K. Rowling’s creation, as do adults—and to a degree never remotely matched in other book sales, running at around six billion to date—might lead us to suspect that it speaks truth to the times. It speaks of a lost search for meaning in the contemporary world and fears that the deep need for teachers, helpers, and other guides on the path from childhood to maturity, is not being met. Harry Potter supplies a fantasy of initiation that succeeds.

To turn to specifics today. All relevant agencies report an alarming rate of increase in anxiety and depression in teenagers over the last decade. Suicide increased 40 percent between 2010 and 2021 in Australian 18–24-year-olds, with rates of psychological distress increasing especially for girls. Over the same period, the rates of American teenagers reporting a depressive episode in the preceding year doubled for girls and increased 74 percent among teen boys.

Just out: Depression among U.S. teen girls doubled from 2009 to 2019 and was up 74% among teen boys, according to just-released data from the gov't administered National Survey of Drug Use and Health. What does this mean? pic.twitter.com/H09Pmo7Bss

— GENERATIONS by Jean Twenge (@jean_twenge) October 29, 2020

There are objective reasons for being more daunted by the entry into adulthood than were earlier generations. There has been long-term escalation of property prices, which have made the old Australian dream of owning your own home seem unachievable for many. There is increased competition for desirable entry-level jobs on reasonable pay. School-leavers are confronted by a vast and confusing array of higher education options, with little guidance to how useful any of them might prove. And once a choice is made, the student may well find themself in a run-down tertiary institution that has lost its way.

But above all, compounding the social problem for teenagers has been the arrival of Internet devices, and with it screen addiction. Pasi Sahlberg found in a 2022 study for the Gonski Institute in Sydney that many teenage boys are spending six to nine hours a day gaming online—half their waking lives. Girls are more inclined to social media than gaming—with its own problems of highlighting social exclusion, triggering self-consciousness, and promoting unattainable ideals of beauty. There is a correlation in girls between depression and increasing time spent on screen. Last year, NAPLAN results for boys were the worst ever in Australia, with literacy declining. The failure-rate for those in Year 9 has doubled since 2008—COVID home-schooling may be partly responsible.

Parents have compromised authority in restricting their children’s screentime, given their own propensity to spend their spare time on smartphone or laptop. The role-modelling is poor. What is happening to a society in which its inhabitants, when out in public—on train or bus, in café or restaurant, in doctor’s waiting room or walking down the street—bury their heads in smartphones? Normal socialising has been switched off; and so has relaxed, contemplative taking in the world around. Not to mention crossing streets or riding bicycles with AirPods in ears, distracting the mind and blocking out warning sounds of danger.

Schools are increasingly banning phones in classrooms, but that does not entirely answer the problem, in that boys especially, and even in primary school, covertly game on their iPads during class.

There are psychological as well as educational consequences. American social psychologist Jean Twenge, in her 2017 book iGen, argues that the rapid spread of smartphones and social media into the lives of teenagers from 2007 was the main cause of a mental health crisis that began soon after—above all, rapidly rising rates of anxiety and depression. The rate of girls having at least one depressive episode almost doubled, as did their suicide rate. Twenge’s book is subtitled: “Why today’s super-connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy—and completely unprepared for adulthood.”

iGen, sometimes termed Generation Z—those born after 1995—is a way of defining the problem. The oldest turned 12 when the iPhone was introduced in 2007. Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt, in The Coddling of the American Mind, argue that the period between 2007 and 2012 was when the social life of the average American teen changed drastically. Social media spread wildly, and teenagers started using Twitter.

The effect on college and university students has been marked. There were positive effects, with iGen members drinking less, smoking less, being safer drivers, and waiting longer to have sex. On the negative side, these kids arrive at university having had far fewer offline experiences than their predecessors; they have grown up more slowly and are less mature; and they spend much less time going out with friends. They are more solitary, more socially alienated, and more given to gloomy introspection.

The COVID years have aggravated the problem, with home-schooling forcing greater isolation and more dependency on devices. Relevant agencies and psychotherapy services have noted the deleterious effects on teenage mental health. With universities, an already existing trend has been accelerated, away from face-to-face teaching and live seminars to online classes. Australian parents are now reporting with horror their late teenage children spending all day in their pyjamas in their bedrooms attending their online classes, lectures, and tutorials—a recipe for depression. At every turn, our society seems to be switching off its socialising, and encouraging a solitary monastic existence spent alone with screen devices.

The origins of cancel culture lie here, coinciding with iGen reaching university. Lukianoff and Haidt argue that heated interaction in public, including the robust exchange of conflicting opinions, builds up defences in the individual, in a necessary toughening up for survival and success in the adult world. Too much emphasis on safety, too much over-protectiveness, will cultivate less robust, more thin-skinned characters with paranoid fears of imagined dangers waiting round every corner out in the public world. As with the body, which needs to catch viruses in order to build up antibodies, the psyche needs some exposure to harsh experience to build up resistance to social hurt.

In America especially, university administrators became hyper-sensitive to the potentially hurt feelings of their students. “Safetyism” arose, promoting a cultural climate in which students come to see words as violence, and speakers polarised into safe versus dangerous. Despite university mission mantras to the contrary, free speech became increasingly constrained, often through self-censorship, with students too anxious to express opinions or argue cases that were feared to be unpopular. Instead of preparing the child or student for the road, universities turned to preparing the road for the child.

On the surface, safetyism is based on a truth: a person should be sensitive to the feelings of others. In the past, it was largely left to common sense, in the case of universities, notably that of the teachers and colleagues, to know where to draw the line on what could be tolerably said in the classroom, and what constrained. But once institutions lose confidence in their traditions and values, they feel driven to formulate rules, and set up regulatory committees, especially in a hyper-sensitive time like our own. In fear of scandal, they risk the drift towards bureaucratic inquisition.

One might be tempted to view childhood not so long ago, nostalgically, as a golden age: sports after school, books, social interactions in the street, and doing homework—with the only screen an hour of television after dinner.

But caution is required in overgeneralising about screen devices. The arrival of the telephone prompted scares that people would stop face-to-face interaction and community would suffer. But it soon became clear that the telephone was no more than a convenience that allowed people to do more frequently and more easily what they had been doing before.

A closer parallel was the advent of television. Robert Putnam published Bowling Alone in 2000, the definitive sociological study of the decline of social capital—the degree to which people socialise together, join clubs and associations, and do voluntary work. Social capital declined markedly from the 1970s in America, as it did here in Australia. Putnam attributed a quarter of the decline to people watching television, on average four hours a day—the first significant impact of the screen. The main factor, however, was the ageing of a generation which had been taught by great depression and world war that survival depends on pulling together, helping neighbours, and working at community ties.

The smartphone and online gaming may well, however, have introduced a distinct new era, one with serious long-term consequences, quite different from the modest changes facilitated by telephone and television. Either there will be a natural equilibrating reaction, with the vast majority of people finding balance in more limited screentime and rediscovering the pleasure of socialising, or we will, as a society, have crossed into alien territory, with as yet largely unknown harms to follow, ones manifest already in escalating rates of teenage anxiety and depression. When the adult world is feared as too difficult and dangerous to enter, older generations have doomed their children to bitter loneliness, lacking in law or attachment, failing to generate any sense of belonging or commitment, and with tepid hopes for their future.

The consequences of the breakdown of rites of passage from child to adult are illustrated starkly and tragically in the Aboriginal case. Once the elders stopped initiating the boys, they condemned new generations to weakened belief in tribal law, and its fabric of moral restraint, increasing the likelihood of individuals sinking into an anomic social state of aimlessness and rootlessness, family breakdown, susceptibility to alcohol and substance abuse, violence, and general hopelessness. Here was the darkest effect of European settlement and the resulting dispossession of the original inhabitants from their country.

For Australia today, however, the parallels stop there. Responsibility for launching new teenage generations successfully on the path to adulthood is not handicapped by having to integrate two very different cultures, as was the case with Aboriginal and British. The current challenge lies squarely with the home culture and its institutions, and failure follows from its own foolish lack of care. The magnitude of the challenge we now face is illustrated in the story of Harry Potter.