China

The Reverse Opium War

Beijing looks the other way, and the deadly medicine sails West just as its natural ancestor once sailed East.

An epidemic is stalking American cities. Every day, men and women die on sidewalks, in bus shelters, on park benches. Some die sprawled in crowded plazas at midday; others die slumped in the corners of lonely gas station bathrooms. Internally, however, the circumstances are the same. They all end their lives swimming in the warm amniotic dream of a lethally dangerous opioid. When it comes, the moment of death is imperceptible: coaxed by the drug further and further from shore, the user simply floats out too far, passing some unmarked point of no return. The heartbeat weakens, the breathing slows and shallows. As soft an end as anyone might wish for.

This is the fentanyl crisis. It may seem strange to connect a very modern and very American phenomenon to a brace of wars waged 200 years ago by the British Empire on the last of the Chinese dynasties. But so the rhetoric runs: we are witnessing a Reverse Opium War; a belated Sinic revenge.

The Communist Party teaches schoolchildren that China was once a glorious superpower, until it was brought low by that subtlest and most devious of British weapons: Lachryma papaveris (poppy tears). Opium sapped the nation’s strength, and when the Chinese authorities banned it, then Britain went to war—twice.

Those wars crippled the Qing and heralded a “century of humiliation” for China—multiple military defeats and lopsided treaties, the Anglo-French looting and burning of the Emperor’s Summer Palace, the Japanese Rape of Nanking and lethal human experimentation by Unit 731—ending only with the liberating forces of Marxism-Leninism in 1949. Now some commentators are telling us that history has inverted, that karma has kicked in.

Before examining this idea, we should remind ourselves of the American predicament. Ten years ago, fentanyl began its steady flow from China to the United States. Within just three years the drug had surpassed heroin to become the most frequent cause of American overdose deaths. Fentanyl is many times more powerful than heroin, and so there should be no surprise that lethality has spiked since the great Chinese flow began: in 2012, heroin topped the list with 6,155 deaths; by 2016, fentanyl was proving three times as deadly, with 18,335 deaths. The opioid’s influence seeps into all corners of the narcotics market, due to dealers hiding it in cocaine, heroin, and ecstasy. And it leaks across social strata, killing the homeless but also the rock star Prince, who passed away in an elevator at his Paisley Park estate after ingesting fentanyl disguised as Vicodin.

Under American pressure, the Chinese authorities agreed to regulate fentanyl analogs and two fentanyl precursor chemicals, but it soon turned out that shipments were being rerouted via Mexico. With this new arrangement, the crisis only deepened: between 2019 and 2021, the opioid killed 200 Americans a day. Last year alone, the DEA seized quantities of the drug equivalent to 410 million lethal doses. That’s enough to kill everyone in the US. Even a pandemic couldn’t stem the flow for long: in fact, Wuhan is one of the world’s most reliable suppliers of fentanyl precursors (a role it played both before and after starring at the eye of the COVID storm).

The booming fentanyl trade does not appear to rely on traditional criminal organisations, in the way that East Asian methamphetamine trafficking depends on the Triads. Instead, it turns out to be small family-based groups and legitimate businesses who manufacture and move the drug. Usually located on China’s south-eastern seaboard—Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong—these groups use the cover of the vast Chinese chemical industry to channel ingredients into the manufacture of fentanyl-class drugs and their precursors.

After preparation and export to Mexico, the usual suspects take over: Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación, Sinaloa Cartel, etc. They develop the fentanyl and move it up over the border, hidden in secret compartments in cars, stashed inside flight luggage, or secreted within the bodies of drug mules. In the US, fentanyl is sold wholesale for as little as 50 cents per pill. But once the product is on the streets (where it trades by the names “Apache” and “China Girl”), dealers will charge far more: up to $3 per pill in South Bronx neighbourhoods like Hunts Point and Mott Haven.

Chinese businesses funnel drug profits from the US to China and then to Mexico, using burner phones and domestic money transfer apps. Singaporean Lim Seok Pheng worked for a Chinese laundering business for two years, and she described the group’s process to a courtroom. A typical job would go as follows:

Miss Lim waits in a public place in Chicago or New York, carrying the requisite burner phone and a dollar bill with a specific serial number. The cartel gives her phone number to a contact, who calls her and provides a code name in exchange for the precise rendezvous details. The contact joins her at the café or park or square, collecting the dollar with its identifying number as a receipt for the handoff. Now saddled with as much as a million dollars in cartel cash, Lim visits a Chinese merchant, and gives him the details for a Chinese bank account. She opens a currency converter app on her smartphone to establish the exchange rate, and the merchant transfers the yuan equivalent from his account in China to the new account she had provided. Then he takes the cash.

No American financial institution is involved at any stage. US drug money is quickly converted into Chinese yuan sitting safely in a Chinese bank, after which the same so-called “mirror transactions” are used to convert the money into Mexican pesos. When sentencing businessman Gan Xianbing in 2021, US prosecutors stated that these new Chinese “brokers” had displaced Mexican and Colombian launderers and “come to dominate money laundering markets.” They called it “the most sophisticated form of money laundering that’s ever existed.”

In a surreal detail, fentanyl precursors are increasingly paid for with wildlife products. China’s businessmen require these for aphrodisiacs, traditional Chinese medicines, and culinary delicacies. The demand is huge, and now cartels actually risk damaging Mexican ecosystems in a never-ending quest for jaguars, jellyfish, porpoise, rosewood, sea cucumbers, and the coveted swim bladder of the totoaba fish. The chaos of wildlife trafficking also makes the spread of zoonotic diseases a far greater likelihood.

The notion of a Reverse Opium War implies, of course, that the Chinese authorities have been consciously orchestrating events. And yet the US opioid crisis was actually underway prior to the fentanyl disaster: the current phenomenon constitutes only the third and fourth waves of the crisis. There were various unrelated reasons for the earlier waves, among them a WHO-backed shift towards the prescription of opioid medication for pain relief. For the past 10 years (the Xi Jinping decade), the epidemic has centred on Chinese fentanyl.

There is some indication that the Communist Party is helpless; that it faces a mammoth task for which it has neither the time nor the energy. Fentanyl precursors are often dual-use chemicals, which greatly complicates the process of supply control. They exist on a “ghost list”: unscheduled, but clearly used for narcotics. We should also remember that in China, the body politic is positively riddled with corruption. After 10 long years, Xi’s “anti-corruption” campaign has made no difference to the average citizen’s bribe-haunted existence (and indeed it was probably never intended to tackle real corruption: Xi just wanted a cover for the removal of his rivals at the top of the Party). In order to move up the chain, officials must achieve economic growth in their jurisdictions—by any means. It was always going to be especially difficult to enforce fentanyl controls in a society with endemic fraud and extortion.

Some Chinese citizens observe the US opioid crisis with contempt, unaware that the drugs actually originated in Wuhan and Guangzhou. And even for Party officials in the know, the lack of a comparable crisis in China probably convinces them that this is an American problem for Americans to worry about—yet another contributor to the great US decline in which they believe so passionately. (Hasty declarations of American demise go back to at least 1970, when the United States was dismissed as “a paper tiger, already in the throes of a death-bed struggle,” in Mao’s mangled metaphor.)

These officials will change their minds quickly if the opioid returns to China in large quantities. The CCP was most uncooperative in the early stages of the international battle against methamphetamine—until consumption became an issue inside China’s borders, at which point the Party became helpful (an indication, perhaps, that opioid supply control may not be impossibly complex after all). Now fentanyl overdose statistics are rising fast in Argentina and the Southern Cone, and even in the UK. Inevitably, the crisis will not remain solely an American problem. Everything that begins in North America soon drifts east; the winds of culture are always westerlies.

But is the Communist Party really just sitting back and contentedly watching an empire decay, trusting in the inevitability of historical power cycles? Or might it be acting to bring about this decline, deliberately waging a Reverse Opium War in an attempt to sap American vigour, just as it believes Western forces once exhausted and eroded the Qing empire?

China, of course, is an aggressive combatant in the global war on drugs. The Party has spent decades approaching the tangled issues of the world of narcotics with all the tact and nuance we might expect from a totalitarian regime: forced labour, executions, life sentences for cannabis possession, etc. More people are executed every year in China than the rest of the world’s countries put together, and the CCP doesn’t even bother to maintain a full record of the (presumably stratospheric) numbers killed for drug offences. The Party’s war on drugs might lead us to dismiss the notion that it would ever wage a war with drugs.

However, the full picture is more complicated. Communist Parties have always viewed law itself as a blunt instrument, devoid of inherent value and meaning. Concepts like truth and justice are means, not ends. As Leszek Kołakowski reminds us, “one can find many quotations in Marx and Engels to the effect that … the law cannot but be a weapon of class power.” And while the CCP has abandoned the economics of Marxism, much of the original philosophy still obtains.

In modern China, criminal syndicates are assessed solely with regard to utility. Law-breaking only becomes relevant when a syndicate turns out to be useless to the Party; the more benefit it can provide, the more protection the government will offer them. This means that for all its bluster, the war on drugs tends to target only small actors. Triads are safe—they have proven consistently useful when it comes to monitoring and intimidating the Chinese diaspora. Project Sidewinder famously lifted the rocks on Party-Triad intelligence operations in Canada: money laundering, intellectual property theft, Party cadres slithering into positions of influence over Canadian politicians, etc. Gangsters and government proved to be natural allies because, under the surface, they had always belonged to the same species.

There is precedent, then, for the conspiracy evoked by theorists of a Reverse Opium War. But—pending further revelation—we have no real evidence of a grand Machiavellian plot. Beijing brings the same cynicism to counternarcotics that it brings to Triad relations, and it is here that we find our best explanation for the escalation of the fentanyl epidemic.

The Party is interested in the maintenance of power, which means that it was always likely to adopt a changeable approach to a drug crisis. Today, after 20 years of fooling the US political establishment with regard to their benevolent intentions, China’s leaders understand that the facade is no longer sustainable. Beijing is recognised by Republicans and Democrats alike for the foe it has always been. And so it has ceased the pursuit of small businesses shipping opioids to Mexico. That pursuit had only ever been aimed at keeping Americans on side—now a hopeless task.

From 2018 onwards, drug war cooperation with the United States declined in concert with the more general deterioration of US-China relations. In August 2022, cooperation ceased altogether. There have been no high-profile Chinese prosecutions since a trial in Hebei in 2019. While state media continues to boast of “an intensified fight against narcotics” and “the strictest drug control in the world,” this rigour does not apply to fentanyl. The opioid’s traffickers have come to enjoy “a great sense of impunity,” says Brookings fellow and organised crime expert Vanda Felbab-Brown. America’s crisis has intensified as a result, and the Party will certainly be enjoying the historical parallel.

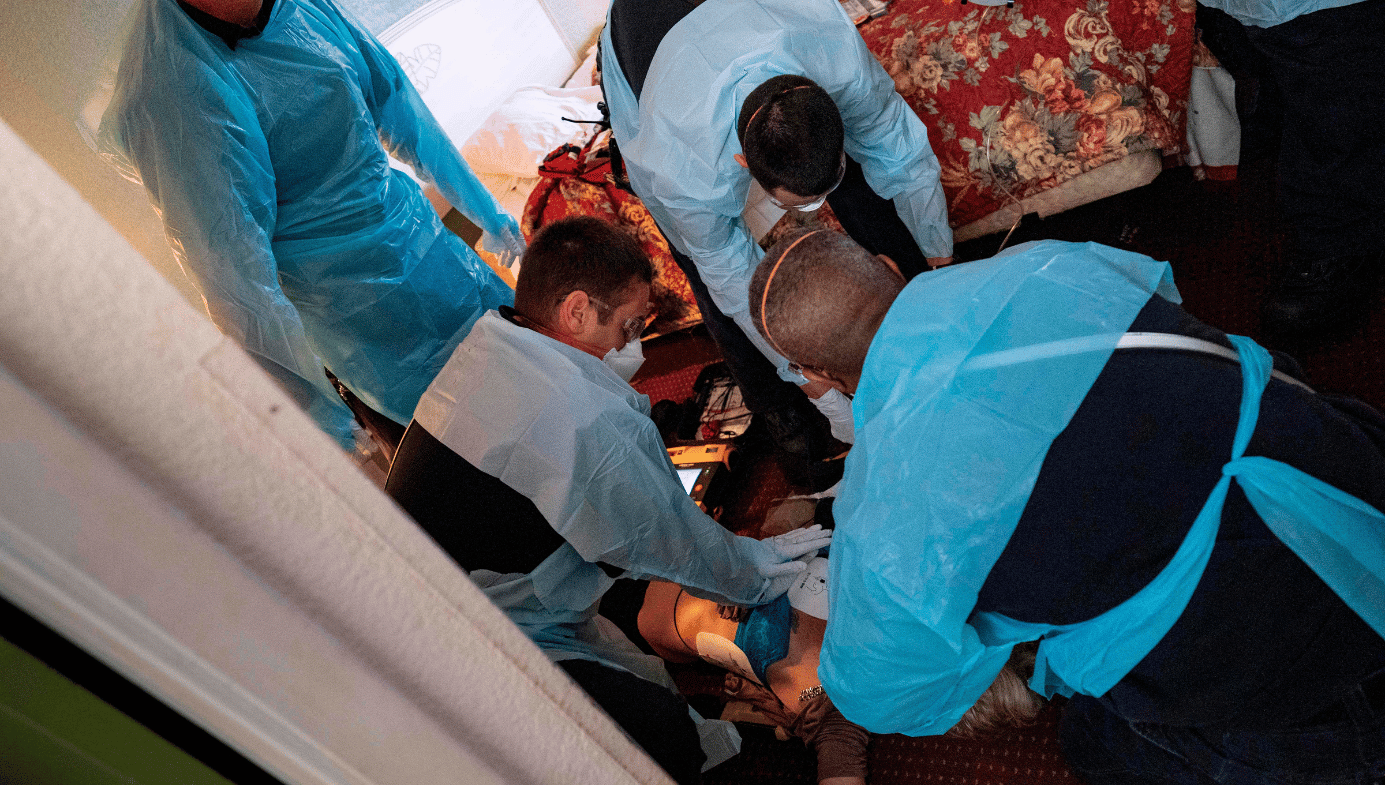

Back and forth across the breadth of the land, ordinary medications are now tainted with “China Girl”—or to use the simplest and most appropriate of all its street names, “Poison.” In December 2019, sociology student Alexandra Capelouto travelled from Arizona State University to her parents’ home for the holidays, spent the afternoon Christmas shopping with her mother, and by the following morning she was dead. The culprit: half a pill of oxycodone spiked with fentanyl. In June 2020, Amy Neville found her 14-year-old son Alexander lying dead on a beanbag in his bedroom at their home in Orange County. He had bought OxyContin on Snapchat, and one of the pills turned out to be laced with fentanyl—enough to kill four people. In July 2021, Kierston Torres-Young (19) passed out while watching Netflix in Vancouver, Washington, and could not be resuscitated. She had taken Percocet, a medication containing oxycodone and paracetamol, but it was neither oxycodone nor paracetamol that the emergency medical technician identified as the lethal ingredient.

The available evidence points to a government withdrawing its support out of cold disregard for the human consequences. It seems most likely that the fentanyl crisis began without the Party’s knowledge, and that China’s leaders, always opportunistic, are simply allowing the development of a situation which happens to appeal to their sense of historical justice. Having found themselves suddenly embroiled in a war they didn’t start, they are now taking steps to perpetuate it.

Why would the Opium Wars—two minor conflicts from the mid-19th century—be at the forefront of Party thinking? In a word: nationalism. We’ve spent the past decade living through a heated age of flag-waving and nationalist frothing. We can hear the same noise in all countries, from one end of the planet to the next. But there is no more passionate advocate of jingoistic glory than the CCP official. Amid the hue and clamour, his voice is always loudest. No matter that “China” remains an unclear concept in his head; that his distinction between country and Party is fuzzy at best; that defending “China’s interests” often requires the crushing of ordinary Chinese citizens: all of this makes no difference to his passion. And Chinese history is never far from his thoughts. He obsesses over it, lovingly nursing grudges, refuses to let them die. He remembers the national humiliations of the twin Opium Wars as if he had experienced them personally.

Much of what is in his head, however, is nonsense. Opium was used in the region we now call China from the eighth century onwards. Eaten or drunk, it was thought to supercharge traditional aphrodisiacs. It may have contributed to the early deaths of 11 out of 16 Ming dynasty emperors. But no taboo existed. By the time of the Qing, tobacco smoking was punished with decapitation, while opium smoking, technically illegal, was highly regarded. It was, says scholar Julia Lovell, “a chic post-prandial; an essential lubricant of the sing-song (prostitution) trade; a must-have hospitality item for all self-respecting hosts; a favourite distraction from the pressures of court life for the emperor and his household.” The richest families would employ an opium chef.

According to the Party narrative, opium only entered China’s bloodstream in the early decades of the 19th century, when Britain began using crop grown in Bengal to solve a trade deficit in its dealings with the Qing empire. By the beginning of the 1830s, opium clippers were delivering 20,000 mango-wood chests every year to the mouth of the Pearl River, each containing about 140 pounds of raw opium balls wrapped in poppy leaves. A decade on, the supply had doubled again. (The Emperor was assured by his advisors that this version of the drug had achieved its potency thanks to the witchy British practice of mixing human flesh in with the poppy-juice.) Addiction spread fast, and as the nation was struggling with numerous unrelated problems, an opium crackdown provided authorities with a catch-all scapegoat.

And so the old nominal ban was enforced. Workers dumped 10 million dollars’ worth of opium into stone pits at the Canton River estuary, adding salt and lime to the mix. Formal apologies were expressed to the Spirit of the Sea before the entire foul-smelling brew was flushed into the waiting ocean—a symbolic draining of the poison from China’s body.

The British were not happy. War crept into existence through episodic spurts and skirmishes, and the Qing military, primitively-equipped and corrupt to the core, was repeatedly routed. At the approach of British forces, Chinese officers would abandon forts, lock their troops inside, and flee: the indignant troops would then turn the cannon on their own superiors rather than the enemy. In 1842, the defeated Qing were forced to pay reparations, permit the expansion of British trade along the south-eastern littoral, and hand over Hong Kong Island.

A decade on, hostilities resumed, triggering a second Opium War. Defeat was still more emphatic this time round. Earlier in the conflict, captured British and French officers had been subjected to bestial tortures; now victorious, British High Commissioner James Bruce (Lord Elgin) retaliated by ordering the incineration of the Summer Palace. His punishment was soberly calculated to fall “not on the people, who may be comparatively innocent, but exclusively on the Emperor, whose direct personal responsibility for the crime committed is established.”

When it looks back across the gulf of years, the Communist Party sees conspiracy. But for most 19th-century British traders, the saturation of Qing China with opium had been greedy and pragmatic. There were no overarching geopolitical schemes. Not only that: by the time of the Opium Wars, the crop was actually grown in vast quantities within China itself, typically earning peasants 10 times as much as rice. As is usually the case in human affairs, chaos rules, not conspiracy.

The imperial court, meanwhile, viewed the first of the conflicts as a mere “border provocation”—no more consequential than other frontier skirmishes of the time (and certainly far less significant than the Taiping Rebellion, which raged alongside the Second Opium War and almost ruptured the country). Beijing remembers it very differently today, framing that period as the nation’s darkest moment; the pitch-black midnight of China’s supposed 5,000-year history. The legend of the Opium Wars is inescapable in modern China. Textbooks, newspapers, monuments, movies: all are recruited in the service of hammering rancour into the national psyche. The CCP casts itself as China’s saviour, reversing the humiliations of history.

And so our approach must be nuanced when faced with Chinese indignation over the issue: the Opium Wars constitute a historical crime, to be sure, but this knowledge is used for the most cynical of purposes by modern authorities. The Party is interested in manipulating the psychology of Chinese citizens, not just in commemorating the dead.

Today’s Reverse Opium War is sustained with a similar cold pragmatism. Beijing looks the other way, and the deadly medicine sails west just as its natural ancestor once sailed east. From a geopolitical perspective, these are petty, inconsequential actions. The American empire is far sturdier than the paper-thin old Qing. But on an individual level, worlds are snapping out of existence every day—continually, needlessly, just to satisfy a deranged belief in historical balance.