Politics

Manufacturing Dissent

Activists and opinion-formers on the Left and Right have been persuaded that living under anything besides the kind of governance they want means they’ve been cheated.

Everyone hates the media, and everyone sounds like a talking head.

~George Packer, “The Hardest Vote”

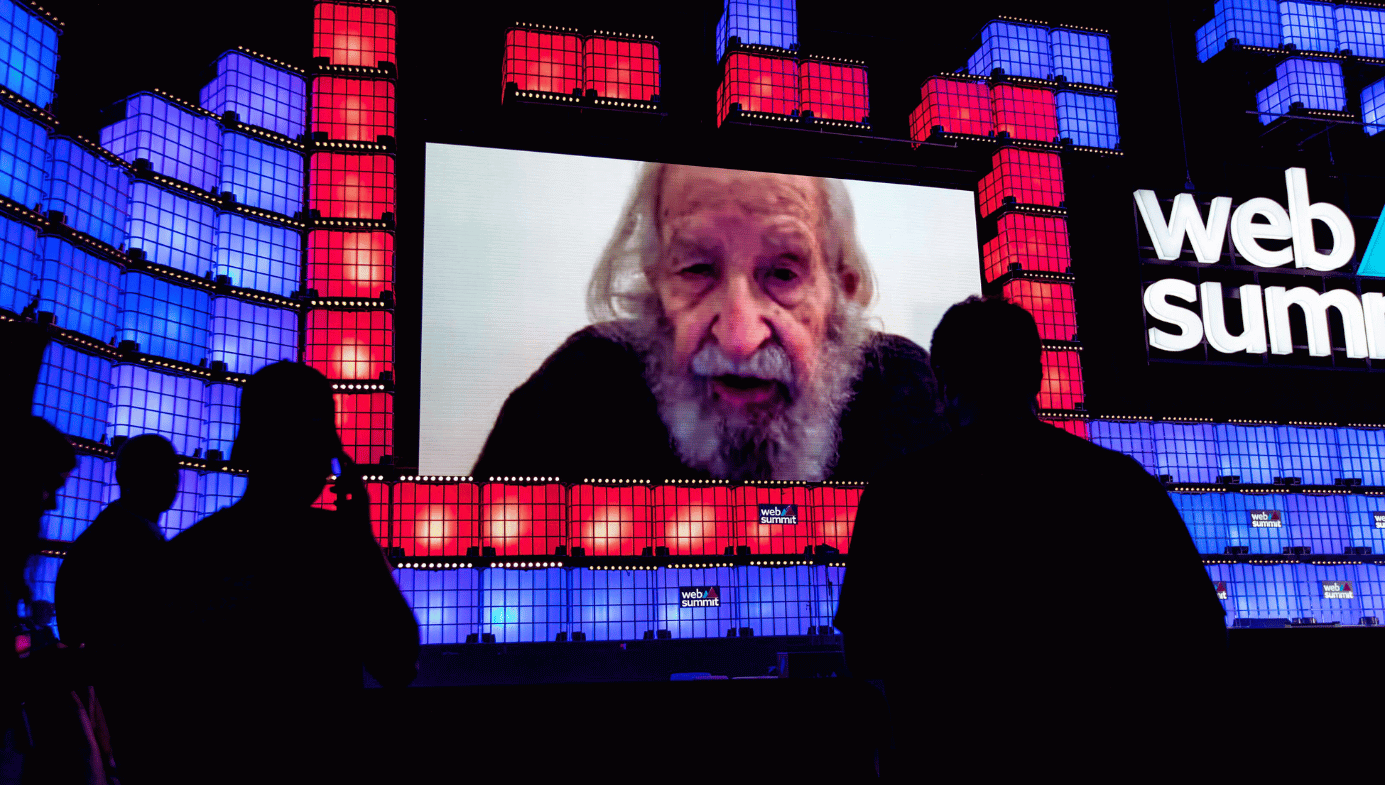

It’s all Noam Chomsky's fault. Well, it’s not directly his fault, but Chomsky’s influence on generations of pundits, political junkies, and ordinary people has been wider than anyone 40 years ago might have hoped or feared. A scholar of linguistics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Chomsky gained international renown with his trenchant criticisms of American foreign policy from the 1960s onward. He also issued warnings about the power and influence of propaganda and mass manipulation in open societies that reached an even greater public, including many who had never read his books or checked his research. Today, a sampling of his observations, once eagerly endorsed by intellectuals and alt-rock fans, sounds like the staple complaints of MAGA Republicans and truck blockaders:

But apart from educated elites, much of the population appears to regard the government as an instrument of power beyond their influence and control. (From Necessary Illusions: Thought Control in Democratic Societies)

See, in most parts of the society, you’re encouraged to defer to experts - we all do it more than we should. (From Understanding Power: The Indispensable Chomsky)

The dominant class recognized that they had to shift their tactics to control of attitudes and beliefs instead of just the cudgel. They didn’t throw away the cudgel, but it can’t do what it used to do. You have to control attitudes and beliefs. (From Occupy)

[The state has] to control what people think. And the standard way to do this is to resort to what in more honest days used to be called propaganda. Manufacture of consent. Creation of necessary illusions. Various ways of either marginalizing the general public or reducing them to apathy in some fashion. (From Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media)

It is also important to understand that privileged and powerful sectors in society have never liked democracy, for good reasons. Democracy places power in the hands of the population and takes it away from them. In fact, the privileged and powerful classes of this country have always sought to find ways to limit power from being placed in the hands of the general population. (From Optimism Over Despair: On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change)

[I]f a political leader says that “I’m doing this in the national interest,” you’re supposed to feel good because that’s for me. However, if you look closely, it turns out that the national interest is not defined as what’s in the interest of the entire population; it’s what’s in the interests of small, dominant elites who happen to be able to command the resources that enable them to control the state. (From Language and Politics)

[T]hose who occupy managerial positions in the media, or gain status within them as commentators, belong to the same privileged elites, and might be expected to share the perceptions, aspirations, and attitudes of their associates, reflecting their own class interests as well. (From Necessary Illusions)

Though these pronouncements sprang from their author’s political leftism, they have been echoed in tracts from the political Right, including Ann Coulter’s Slander: Liberal Lies About the American Right (2002), Bernard Goldberg’s Arrogance: Rescuing America From the Media Elite (2003), Gregg Jackson’s Conservative Comebacks to Liberal Lies (2006), Tim Groseclose’s Left Turn: How Liberal Media Bias Distorts the American Mind (2011), Derek Hunter’s Outrage, Inc: How the Liberal Mob Ruined Science, Journalism, and Hollywood (2018), Jeanine Pirro’s Liars, Leakers, and Liberals: The Case Against the Anti-Trump Conspiracy (2018), L. Brent Bozell’s Unmasked: Big Media’s War Against Trump (2019), Mark Dice’s The Liberal Media Industrial Complex (2019), and Amber Athey’s The Snowflakes’ Revolt: How Woke Millennials Hijacked American Media (2023).

Along with the unironic “Fair and Balanced” branding of Fox News, and the late radio host Rush Limbaugh’s routine denunciations of a vague, sinister force identified only as “The Media,” these polemics seem to derive from Chomsky’s fearful suspicions about the control and indoctrination exercised by news, education, and entertainment. Ann Coulter and the producers of Fox News didn’t need to quote Noam Chomsky directly in support of their own positions—indeed, they may never have read him at all. But somewhere along the line, they and their peers—and their audiences—absorbed Chomsky’s message.

Not that the message was new exactly. Criticism of mass media’s undue effects on entire populations is almost as old as the mass media itself. The classic dystopias of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) and George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) imagined, respectively, the enervating distractions offered by “feelies” and the Ministry of Truth, while Marxists Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno examined the deceptive fantasies purveyed by Hollywood and popular music in Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947). Vance Packard’s The Hidden Persuaders (1957) alleged that businesses were inserting subliminal imagery into cigarette and alcohol ads to trick consumers into spending against their rational judgment. Further toward the fringe, antisemites like Father Charles Coughlin and Henry Ford condemned the supposed Jewish domination of the movie and publishing industries, and therefore of public opinion generally. But it was Chomsky, with his academic background and prolific output as an author and lecturer, who brought the appearance of scientific rigor to claims that others had floated out of abstract social theorizing or sheer bigotry. His ability to advance his arguments with clear and unequivocal matter-of-factness won over flocks of new believers.

Most of Chomsky’s political books take on globalization, neoliberalism, and US involvement in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, or Central America. His two key texts devoted to media analysis were 1988’s Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (co-authored with Edward S. Herman) and a compendium of his talks aired on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 1989’s Necessary Illusions: Thought Control in Democratic Societies. In 1992, Canadian filmmakers Mark Achbar and Peter Wintonick adapted the former volume into a three-hour documentary titled Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media. This film delivered Chomsky’s arguments to ordinary people well outside his usual cohort of students and activists. It was initially screened in metropolitan theaters, but it soon became available everywhere in the new medium of home video. “The film, like its subject, is challenging without being wild-eyed, controversial without stooping to aphorism,” ran a review in the Toronto Globe and Mail. “At the very least,” the Chicago Sun-Times conceded, “Wintonick, Achbar and Chomsky encourage viewers to scrutinize what they read, see, and hear.” Did they ever.

Since then, Chomsky has become a cult figure for progressives, with major rock acts including Pearl Jam and Rage Against the Machine promoting his works. A second biographical documentary, 2003’s Rebel Without a Pause, took its title from a compliment paid to Chomsky by U2’s Bono (lifted, in turn, from the title of a Public Enemy track). During those years, there was no shortage of other writers elaborating on—or simplifying—Chomsky’s basic premise: Norman Solomon’s The Habits of Mainstream Media: Decoding Spin and Lies in Mainstream News (1999) and Target Iraq: What the News Media Didn’t Tell You (2003), Lewis Lapham’s Gag Rule: On the Suppression of Dissent and the Stifling of Democracy (2004), Elliot D. Cohen’s anthology News Incorporated: Corporate Media Ownership and Its Threat to Democracy (2005), John Nichols’s Tragedy and Farce: How the American Media Sell Wars, Spin Elections and Destroy Democracy (2005), and Amy and David Goodman’s Static: Government Liars, Media Cheerleaders, and the People Who Fight Back (2006). There was also the pop paranoia of the Disinformation Company, publishers of You Are Being Lied To: The Disinformation Guide to Media Distortion, Historical Whitewashes and Cultural Myths (2001), Everything You Know Is Wrong: The Disinformation Guide to Secrets and Lies (2002), 50 Things You’re Not Supposed to Know (2003), and Abuse Your Illusions: The Disinformation Guide to Media Mirages and Establishment Lies (2003), as well as the annual Project Censored yearbooks.

According to each of these, the ultimate source of the spin, suppression, and static is the US-based capitalist economic order. Chomsky and his disciples weren’t simply advising people to delve past the headlines and soundbites for a sharper understanding of current affairs, which would have been good counsel. They were also warning that campaigns of omission and deception are deliberately orchestrated to prevent any such understanding. This was the “propaganda model” described by Chomsky and Edward Herman in Manufacturing Consent. “The media,” Chomsky explains in Necessary Illusions, “serve the interests of state and corporate power, which are closely interlinked, framing their reporting and analysis in a manner supportive of established privilege and limiting debate and discussion accordingly.” Or as Carl Jensen of Project Censored put it in 1996: “[T]he bottom line explanation for much of the censorship that occurs in America’s mainstream media is the media’s own bottom line.”

Funny thing, though—by this point, the notion that the journalistic establishment was a tool of powerful elites had already been embraced by a separate constituency of readers and listeners, except the elites they detected were not those identified by Carl Jensen, Amy Goodman, and Noam Chomsky. The process of manipulation was not in dispute—all seemed to agree that popular consent is manufactured and illusions are necessary to keep us in line. That left the questions of exactly what we are consenting to and through which illusions. The Right, no less than the Left, found plenty of evidence to back its theory that almost everything dispensed by big newspapers, networks, and studios could be construed as lies, disinformation, and propaganda. Conservative pundits identified the spread of R- or X-rated cinema and television, the investigative reporting that focused relentlessly on Republican political scandals, the constant attention given to the grievances of this or that new class of victims, the commonplace portrayals of military or business leaders as dangerous villains, and the steady debunking of historic heroes as racist white males. Sometimes, the same outlets excoriated by one side were targeted by their opponents for different reasons. While Chomsky attacks the New York Times as a mouthpiece of the military-industrial complex, for instance, Ann Coulter and Fox News’s Sean Hannity described the paper as a shill for liberal relativism. They all agreed that the media was intentionally misleading the people to fulfill a larger, secret agenda—they just disagreed about what the agenda really was.

And here we arrive at Chomsky’s legacy of bipartisan paranoid grievance. In 2023, nearly every platform of information and opinion is characterized as either Ours or Theirs, depending on who’s assessing it, and commentators with millions of followers complain that they’ve been shut out of the public conversation. With the emergence of the Internet and social networking, even those who can’t tell Karl Marx from Mark Zuckerberg routinely insist that a concerted system of some kind or another is inculcating mindless obedience in a gullible public. The reliability of coverage varies and some sources strive a lot harder for neutrality than others. But try telling that to your neighbor or relative who’s lost down a rabbit hole of YouTube videos and QAnon posts. Today, it’s dissent that’s mass-produced, and useful consensus on any big topic is a distant ideal. Chomsky may not have invented this suspicion, but he did more than most to create the intellectual climate for its popularization. It was Chomsky who made it fashionable to discredit the official accounts of any event. It was Chomsky who formulated the paradoxical logic of decrying media bias through the media.

“There are all sorts of filtering devices to get rid of people who are a pain in the neck and think independently,” he said, independently and unfiltered, in 1997. In Necessary Illusions, he set out the unfalsifiable parameters of his reasoning, which so many others would adopt: “The propaganda model does not assert that the media parrot the line of the current state managers in the manner of a totalitarian regime; rather, that the media reflect the consensus of powerful elites of the state-corporate nexus generally, including those who object to some aspect of government policy, typically on tactical grounds.” That is, even dissent isn’t really dissent, since it merely shows that authorities are fooling us into a false sense of autonomy. This insidious scheme may be why the Canadian edition of his book features the cover blurb, “National Bestseller—More than 50 000 Copies Sold,” and why Jeanine Pirro, Sean Hannity, and Tucker Carlson, fronting their own published blasts against the mainstream media, are likewise advertised as “New York Times Bestselling Authors.”

In fairness, Noam Chomsky has never advocated physical violence against individual reporters, and nor has he quite pronounced, as President Donald Trump did in 2018, that the press is “the enemy of the people.” Yet in a subtle and sophisticated way, he helped to make such threats attractive. Activists and opinion-formers on the Left and Right have been persuaded that living under anything besides the kind of governance they want means they have been cheated—any statement I disagree with is purposefully fraudulent; anybody who doesn’t see things my way has been brainwashed; democracy is only working when my team wins. Far lesser minds than his parrot those ideas today, for which Chomsky, now in his 95th year, shouldn’t be blamed. But he deserves some measure of culpability for our contemporary crises over objective knowledge, expertise, and authority. Over a long and prominent career, he made it seem rational—and even admirable—to reject them.