Art and Culture

Low Life and High Style

Cruel, indiscreet, misanthropic and miserable, columnist Jeffrey Bernard nevertheless produced some bracing and scabrously funny journalism.

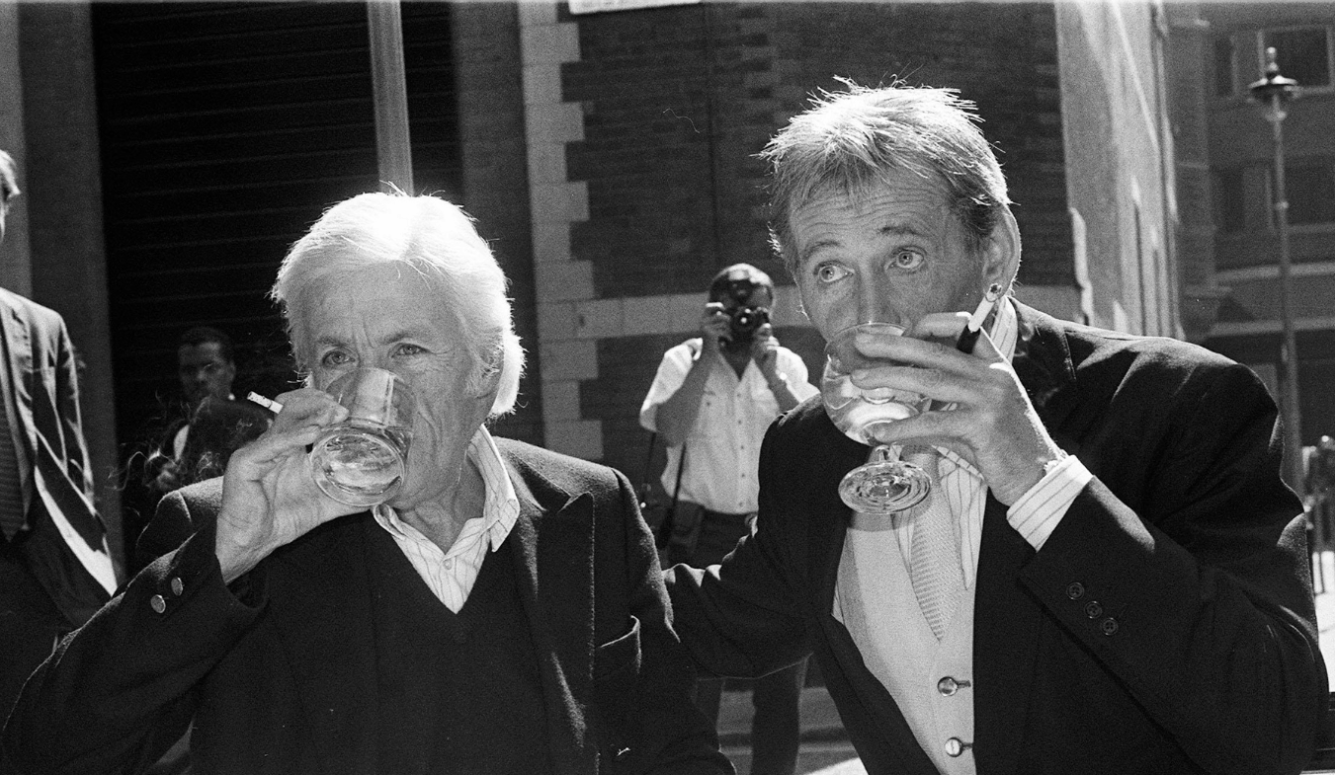

Any lunchtime visitor to London’s media haunt the Groucho Club during the early 1990s would have noticed a peculiar figure slumped in one of the armchairs. The man—probably in his late 70s, judging by his appearance—had raffish grey hair and two lumps the size of nectarines growing out of his neck that gave him the appearance of a strange creature in a Lewis Carroll tale. His unfocussed stare peered at the world—or scowled at it—through a blue haze of cigarette smoke and alcohol fumes. He was usually alone, but if he had company, you would hear him periodically grouch out pessimistic comments on the human condition.

“People are terribly self-interested, aren’t they? I mean, I’m always amazed if I see someone doing something selfless.” Or perhaps, “Life is mostly boring and fucking miserable, isn’t it? I mean, the days when you’re actually happy are the exception, not the norm.” Remarks like these would be spoken in a kind of dirge, as though each word cost the speaker blood. But the voice that uttered them was strangely beautiful, even adolescent, belying the ravages that time and a dissolute life had wreaked on the body. The name of this person was Jeffrey Bernard, he had just turned 60, and he was then the most famous and celebrated journalist in London.

Bernard was certainly not a man celebrated for his virtue. He had been married four times, unions which had all been casualties of his addiction to drink (first whisky and later vodka), his deep—almost adulterous—love of horse-racing, and a hopeless addiction to gambling, all of which he wrote about in his weekly Spectator column “Low Life.” He claimed to have seduced at least 500 women, including the wives of his friends, and he seemed to model himself on his hero Lord Byron—mad, bad, and perilous to tangle with.

Soho was his stamping ground. He’d discovered it as a teenager following his expulsion from the naval college to which his opera-singer mother had sent him. It was love at first espresso and from that moment forward he had, in his own words, “never looked upwards.” By the 1980s, Soho had plummeted since its heyday, when it was a rich melange of Italian delicatessens, Greek restaurants, violin shops, poets, painters, prostitutes, and gangsters. Yet Bernard kept faith with it, returning to the Coach and Horses on Greek Street each morning with the grim resignation of a commuter.

That pub, made famous in his weekly column, was presided over by landlord Norman Balon, a man (still with us) of legendarily mean and rude temperament, which disguised (or so his advocates claim) a heart of gold. Bernard compared him variously to Fagan, Wackford Squeers, and a Frankenstein’s Monster he and other journalists had created in their writing (the pub was the site of Private Eye lunches too). In print, the Coach and Horses provided the perfect backdrop to Bernard’s musings on the deaths of friends who succumbed to alcohol and tobacco-related diseases and his own health complications caused by diabetes and pancreatitis. These were accompanied by sundry reflections on his two most enduring pursuits: pursuit by the Inland Revenue for unpaid taxes, complete with court appearances and bankruptcy threats, and pursuit of an endless succession of ladies—“sphinxes without secrets”—who usually abandoned him with a feeling of immense disillusion and the hissed accusation: “You make me sick.”

These columns brought him a cult readership, but they were not responsible for making Bernard the Talk of London. This was accomplished by Keith Waterhouse, a Leeds-born powerhouse of a writer who seemed to be everywhere for a while—in newspapers, novels, plays, and even books on English grammar. A few years prior, Waterhouse had walked into the Coach and Horses with a surprise for Bernard. He proposed to turn the writer’s Low Life columns—a catalogue of woes and comical indignities—into a stage play. Titled Jeffrey Bernard Is Unwell (the explanation invariably provided by the Spectator whenever the writer was too drunk or sick to file his column), it went on to star Peter O’Toole and became a massive success, playing to packed houses after it opened in 1989. It was subsequently revived three times over the years to exuberant receptions. On the way to his perch at the Coach and Horses, Bernard could now stop off in Shaftesbury Avenue and see his name in lights. It was a staggering coda to a life in which all efforts at betterment, it seemed, had been given the swerve.

The play’s arrival at the end of the Thatcher decade, like the columns on which it was based, caught the zeitgeist in mysterious ways. While Thatcher had shovelled the notions of hard work, streamlining, efficiency, and productivity down Britain’s throat like so much cod liver oil, Bernard’s life was a grand, inebriated shrug, even a yawn, at all these exhortations. He would no doubt have made Thatcher sick, too. She certainly would have disapproved of his CV. He never managed to keep the many and various jobs he had held at one time or another: bookie’s runner, dirty bookshop attendant, theatre stagehand, dishwasher, navvy, actor, coalminer, boxer…

Occasionally, looking back at a life swallowed by vodka, he would comfort himself that, “Without alcohol, I would have been a shop assistant, a business executive or a lone bachelor bank clerk. … How must a bank clerk feel when he sees the clock moving towards opening time or the first race?” His attitude to job security seems to have mirrored his attitude to gambling: “The fun lies in putting yourself at risk and then getting out of the shit. There’s no fun unless the stakes are more than you can afford.” He always preferred, he said, people who’d had experience of ruination: “Skating on thin ice keeps a man on his toes.”

Even in his fated profession, journalism, Bernard was constantly slipping up. He was sacked by the Daily Mirror and kept his editors at the Spectator on tenterhooks waiting for his copy. For a while, he wrote a highly successful column for Sporting Life on the racing community about losing, and made fun of the more self-important figures in that world. But he was sacked there too when he passed out at a dinner instead of delivering the speech he’d been hired to make. This followed the notorious occasion when he disgraced himself by throwing up over the Queen Mother at Royal Ascot. Appalled eye-witnesses reported half-digested tomato-skins spattering the QM’s pristine tights.

Had Bernard just been a drunk with literary talent—a kind of British Bukowski—he would not have been especially remarkable. But his writing often reached for something more noble. His copy, when it arrived—if it arrived—was usually immaculately clean. He had a style of hammering out his prose with as few commas as possible, like a prize racehorse effortlessly clearing jumps. When Sue Lawley interviewed Bernard for Desert Island Discs, she giggled skittishly at the old rogue, spoke of his immaculate shirts and highly polished shoes, and marvelled at his near-encyclopaedic knowledge of Mozart’s music. His column included digressions on how to make perfect mashed potato fortified with cream and egg yolks—“the potato must be whipped, not mashed”—or instruct his readers in how to cook a fine chicken with tarragon, lemon juice, and cream.

Like any decent writer, Bernard had his strong loves and hates, and didn’t hesitate to let his readers know about them—good writing, as Orwell said, is done by those who are unafraid. On the love side were Mozart, jockey Lester Pigott, the actress Veronica Lake, the racing town of Lambourn, novelist Graham Greene, the Duke of Wellington, and Lord Byron. Those on his hate-list included students, the uneducated young, pop music, Napoleon, travelling salesmen, men with tattoos and women with sunglasses on their heads, nouveau riche Arabs, football hooligans, the Arts Council (Bernard fantasised about slaying its members one by one in Hyde Park fencing duels), and young well-heeled media types “with no self-doubt whatsoever.”

Bernard also swam aggressively against the rising tide of radical feminism. When the Groucho Club lent him a couple of books by the Australian feminist Dale Spender, he told his readers that “so full of hate are they that it burnt my fingers to turn the pages. … I shall return the books to the club today as gingerly as if I were disposing of nuclear waste. Far from exploiting women I don’t even notice them anymore.” (Spender, Bernard wrote, had also tried to get him barred from the Groucho Club for swearing.)

These fulminations were routine, but novelists Alice Thomas Ellis and Graham Greene both, despite everything, suggested he shared qualities with holy figures. Greene expanded that a saint could be a sinner and a sinner a saint, while Thomas Ellis was surely struck by Bernard’s lack of material possessions and his ability to abandon himself to wherever fate or Smirnoff led him. Of one windfall snatched by the Inland Revenue he wrote, “I was going to spend the money on furniture for my new flat but you don’t need more than a bed, a typewriter and a corkscrew.”

A 1987 episode of Arena devoted to Bernard found him in a rented room on Great Portland Street, adorned with just a few framed photos of his minor achievements and encounters with the famous, an overflowing ashtray, a dial telephone, a couple of rubber plants and not much else. In the middle of his desk sat the famous typewriter he christened “Monica Electric Deluxe,” on which he hammered out his 600-word confessionals with two fingers—they were like a letter to each reader or, as Jonathan Meades put it, “a suicide note in weekly instalments.”

Then there was the bed he sat in—the scene of multiple seductions. Bernard christened his room “The Great Portland Street Academy for Young Ladies.” When he was alone, he would lie in it, smoke copious cigarettes, drink endless cups of tea and brood about the past. Bernard excelled at dwelling bitterly on life’s defeats and petty injustices. He became, as his biographer Graham Lord put it, the quintessential “Prophet of Loss.”

He also brooded about the present, which was almost always unsatisfactory. “What I hate is that I know exactly how the rest of today is going to go,” Bernard wrote in 1987, two years before finding fame and his name in lights on Shaftesbury Avenue. Everyone, he suggested, felt trapped in their lives and unable to break out of them: “I lay awake for hours last night trying to work out whether it might be possible to change [my] life. I don’t think it is. It takes a supertanker something like 20 miles to stop, I’m told, and even this dinghy can’t change course…”

So many of his columns start bleakly—“It’s been a perfectly awful week”; “The last few days have been about as bad as can be”—but this was usually a sign that this week’s offering would crackle and pop. Bernard was at his most diverting when wallowing in gloom. Those early morning cigarettes, the gallons of tea, and the remorse he felt staring at the photographs of his wives on the walls (he mostly remained on good terms with them, despite everything) were, like reading about his insomnia or hospital stays, oddly cosy. Much cosier to read about, I suspect, than they were to live through. Bernard told us about his fits of sobbing, his suicide attempts, the period of sobriety he imposed on himself after he punched a female friend one day while in his cups: “I’ve never met such boring people as my friends when I was sober, never been so miserable or so lonely.”

After just two years, he packed sobriety in for good. His column certainly benefitted from that decision, even if he didn’t: drink was the banana skin he so often slipped on. “A couple of days ago, when I woke up and got out of bed, I found a paper-clip in my pubic hair. I don’t keep paper-clips and I am not having an affair with a secretary. … A mystery.” He found peas in the ashtray, curry in his shoes, an omelette on the floor, a mysterious note—he knew not from whom—by the side of his bed: “Would you like to try again some time?” One morning, he upset his cup of tea into the bathwater in which he was sitting: “I didn’t get out at once but lay there in the hot brown water in a sort of resigned despair. Have we travelled thus far, I thought, to end up resembling a tea bag?”

Life was full of such desolate mysteries. Why did the toast invariably fall butter side down? Why were people who opened conversations with “Let me tell you my philosophy of life” so deeply depressing? Why did the realisation that you love and need something so often coincide with it being snatched away from you forever? When he was kicked out of Great Portland Street, he found himself living bang opposite a genito-urinary clinic, the air-conditioning unit of which blew right through his open window. What celestial authority had ordained that bit of bad luck? Was God playing a joke on him?

All this was more grist to an increasingly decrepit mill: “I’ve been awake all night thinking about it, bathed in the light from the wards of the genito-urinary hospital opposite my windows. I have been wondering about the inmates there as well. It strikes some sort of terror in me but it isn’t so much the genitals that need love, care and concern as the mind and metaphorical heart.” And later, slamming the window on the offending air-conditioner: “God knows what germs it is pumping out in my direction. I don’t want anything else to go wrong with my genitals. They have already ruined my life.”

Bernard didn’t lack supporters—the actor John Hurt, a drinking companion, called him “effervescent … [with] an electricity, presence, and he struggles for honesty. And he was uproariously funny in the old days.” Irma Kurtz, Bernard’s self-appointed “agony aunt” (also her job for Cosmopolitan magazine) said his company was “a constant delight” and that he had “the most beautiful smile I’m ever going to see … like a naughty angel, or a little devil caught out in an act of charity.”

But one must resist the temptation to glamorise Bernard. Many of those who knew him well were damning. “You’re a mean little alcoholic, diabetic prick,” one woman shouted at him before departing. “He was a nightmare to work with,” said Spectator editor Alexander Chancellor, “Self-obsessed and a great bite-the-hander.” His agent Jane Conway recalled: “He was a little shit … a certain amount of charm, but it wore thin after I’d known him for a bit.” The journalist Geraldine Norman, who’d finally ejected him from her Great Portland Street flat, explained: “I couldn’t bear living with his unhappiness. He was so intensely unhappy, he hated himself … there was a deep unhappiness around the place.”

Just the One: The Wives and Times of Jeffrey Bernard, Graham Lord’s 1992 biography of Bernard, is a chastening read. The man’s style and staying power (suicide bids notwithstanding) was striking, but he was often loathsome. By his own admission, Bernard destroyed the marriage of one of his friends—Pete Arthy, the first man to give him a room in Soho—by bedding his fiancée on the eve of their wedding. In his column, he wrote amusingly about a secretary at the Mirror who wept constantly into her typewriter over him, and Lord revealed why. Sworn to secrecy over their tryst, he informed nearly everyone in the office of his conquest the next day, leaving her mortified at her desk. It is just as mortifying to read about.

Alcohol no doubt contributed to both episodes and much other misbehaviour besides. If Bernard hadn’t been a serial transgressor with all the discretion of a gossip columnist, he would surely have had nothing to entertain his readers with. Graham Lord remarked that writing about Bernard, he’d found “a deep dead darkness so desperate that I began to dislike more than I liked. But three months later the dislike had matured into an understanding of and sympathy for a painfully complex man and a finer, more balanced admiration for his work and courage.”

It is difficult to imagine Bernard keeping up his commentary in 2023. In the Kingdom of the New Morality, he would be a folk monster. In collections of his journalism, a crime against political correctness appears on almost every page, along with some full-blown felonies. When Year Zero of the cultural revolution finally arrives, Bernard’s essays and books will surely be among the first thrown into the fire. Grievance studies departments could hope for no better example of just how morally reprehensible the Bad Old Days were. And yet, in a review of one of his books, the London Evening Standard described him as “Liberated, humane, honest, observant … moving, and above all extremely funny.” All of which is true. Are today’s crop of teachers, I wonder, training their students to recognise those qualities, even as they scour a writer’s work for evidence of -isms and -phobias and other kinds of moral indecency?

Bernard died in 1997, aged 65. He’d always predicted his death would coincide with the Queen Mother’s, eclipsing his own completely. In the event, his expiration was sandwiched between the deaths of Princess Diana and Mother Teresa, to which his last gasp was a mere footnote. His final years—once the excitement of the play subsided—were not the happiest of his life. Following the amputation of a leg (he immediately asked a friend to buy a stuffed parrot to put on his shoulder), he remained virtually housebound in a Soho flat, visited by friends and helpers though not, he said, always the ones he wished for.

The drinking and smoking continued but the womanising, for obvious reasons, dried up. “A certain amount of loneliness is beginning to creep into my life,” he wrote in one of his late Spectator columns. “Very different from being alone, which I like—and it has prompted me to put an advertisement into the personal columns of this journal stating quite simple, ‘Alcoholic, diabetic amputee seeks sympathy fuck.’”

He found life in a wheelchair endlessly frustrating, and neither Prozac nor the endless ministrations of his female helpers were enough to stave off the anguish. “Racehorses, vodka, Soho and a sprinkling of disgruntled women seem to be the ingredients of a life made even more boring by the fact that at last, after five months, I am getting desperately fed up with existing on one leg. Yesterday, my wheelchair got stuck in the narrow doorway of my kitchen and I could have screamed.” In the end, he opted for the exit, renouncing his kidney dialysis sessions and passing supervision of his treatment to the Grim Reaper. He died at home, surrounded by friends, drinking his sainted vodka to the last.

Looking back, Bernard chose a good moment to leave. It was one second to midnight in an analogue world that had endured for centuries. Within a year of his death, many of us were venturing online, sending our first emails and marvelling at the strangeness of unfamiliar http web-addresses and the hitherto unused @-sign. A few years later, the smartphone camera appeared, a deathblow to the kind of licentiousness Bernard had embodied, along with the ability to upload it all onto YouTube. Bohemia, which had been in terminal decline for decades, was now dead, and there would be no resurrection. Nobody could afford public indiscretions—or even private ones—anymore. Meanwhile, a generation reared on Instagram and TikTok would, as the writer Darren Coffield put it in his lament for Soho, “rather message a stranger on the other side of the world than converse with the person standing next to them at the bar.”

We’ve all changed and settled down now, and we’re terrified of making anyone sick again: the projectile vomit of angry Twitter mobs, drunk on apoplectic virtue rather than Smirnoff, crosses borders and oceans in an instant and has proved to be corrosive in its bile. The spirit of Jeffrey Bernard has left Soho and it isn’t coming back, not even for just the one. Yet we still have the strong liquor of his journalism—intolerant yet broad-minded, cruel and irreverent, self-pitying but scabrously funny. As much a jolt to the spirit as opening time, in fact, and the perfect corrective to the washed-out, passive-aggressive pieties of our times.