Detransitioning

Every Gender Identity Is ‘Authentic’—Until It Isn’t

Faddish forms of self-identification often reflect subjective feelings that shift over time. Let’s stop treating them as sacred truths.

In December 2020, the former Ellen Page publicly announced a new transgender identity. This announcement came after six-and-a-half years of living and celebrating an openly lesbian life, including nearly three years in a lesbian marriage. Ellen suddenly became Elliot. Overnight, both social and traditional media adapted to this new reality, as referential pronouns were quickly revised and the past was rewritten or redacted. The narrative of Page’s life was reworked to accommodate a new gender “truth.” Now, Page’s former lesbian life could be seen as the (unconscious) expression of a heterosexual identity, one that was punctuated with a heterosexual marriage, a sort of stepping-stone on the way to the most recent claim of authenticity.

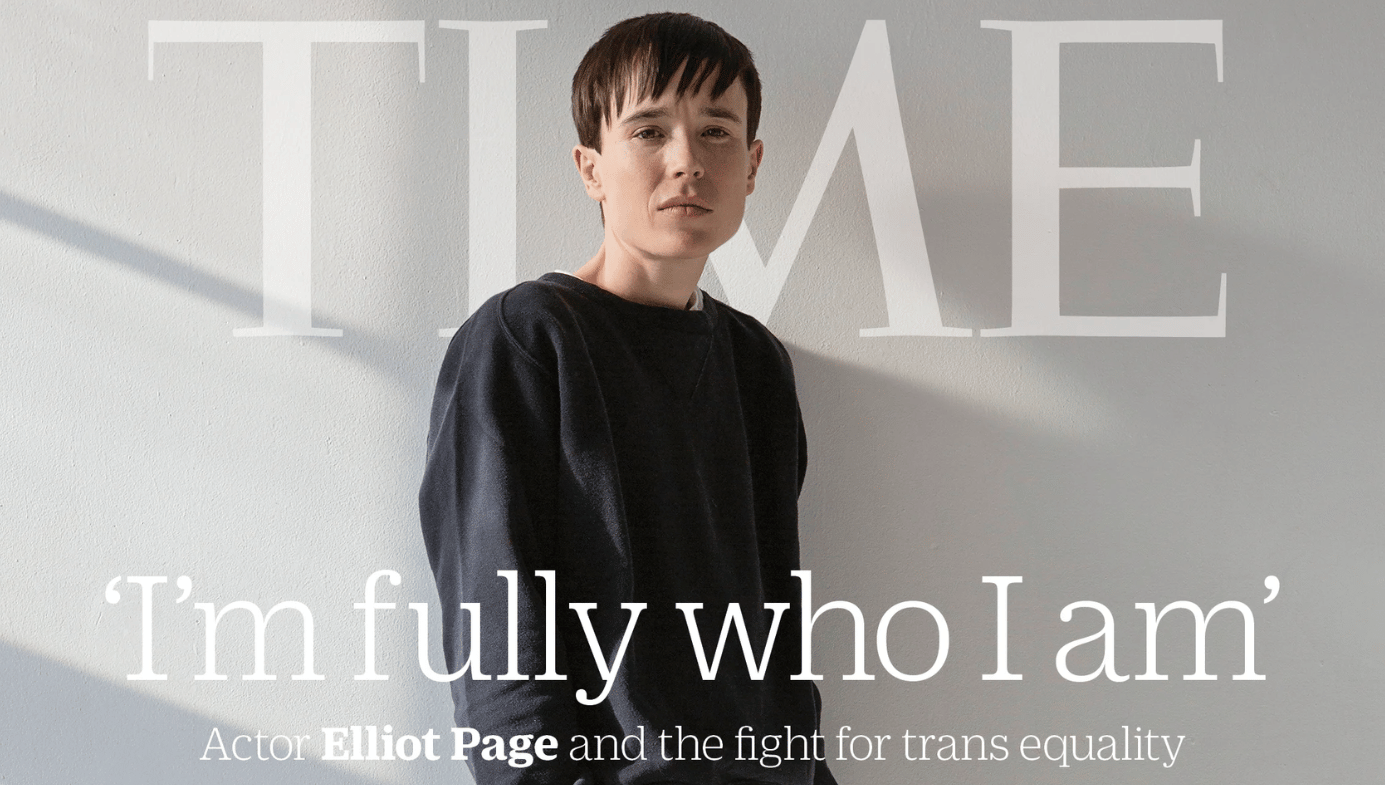

For many on the cultural left, there was an immediate rush to praise Page’s announced discovery of a true or “authentic” self. Hillary Clinton, for example, tweeted: “It’s wonderful to witness people becoming who they are. Congratulations, Elliot.” An interview with Oprah and a Time magazine cover story followed. Page’s public revelation was heralded as an act of bravery, emblematic of the actor’s willingness to “speak his truth.”

It’s wonderful to witness people becoming who they are. Congratulations, Elliot. https://t.co/6vdKuH2slV

— Hillary Clinton (@HillaryClinton) December 2, 2020

It’s easy (or convenient) to forget that when Page—then Ellen—came out as lesbian in 2014, she similarly presented it as a bold act of truth-telling, proudly proclaiming, “I am gay … I am tired of hiding … I suffered for years because I was scared to be out.” She stated that it was vital “to be authentic, to follow my heart.” She had seemingly found and embraced her true (lesbian) self.

But apparently, that supposedly authentic truth was in fact counterfeit: In 2020, Page, now Elliot, stated, “I can’t begin to express how remarkable it feels to finally love who I am enough to pursue my authentic self.” Elliot also reported in the interview with Time magazine, “I’m fully who I am.” Page has therefore managed to find an “authentic” self at least twice—not counting the actor’s pre-2014, pre-LGBTQ+ life, during which there was no public mention of being either L or T.

Page’s story requires us to re-interpret the actor’s once-authentic-seeming 2014-era expression of lesbian pride as an artifact of self-deception and/or inadequate self-love. Indeed, Page’s lesbian years are now categorized as a period of suffering, oppression, and deceit, with a CBC journalist summarizing it this way: “Page recalled knowing his true identity at age nine when his mother allowed him to cut his hair short—and talked about the happiness he feels with having short hair again.” Oprah followed this narrative in her interview, saying, “all the trauma aside that it took you to get here, the courage that it took you to stand within the truth of yourself and to do the thing that you’ve always known you needed to do” (our emphasis).

Which all sounds very nice and uplifting. But it doesn’t actually make any sense: an “authentic” self that can be summarily abandoned in favor of some new (supposedly more authentic) self is, by definition, inauthentic. In Page’s case, how does anyone know that the actor’s replacement authentic truth won’t itself be renounced in favor of some more exotic (and, of course, more authentic) gender classification?

The question brings us to one of the odder aspects of what some call “gender ideology”—the system of beliefs that casts gender identity as a soul-like spirit marker lodged within every one of us, completely independent of biological markers of sex, and utterly unknowable to the world except through acts of self-identification.

The ideology asserts that individuals are capable of unerringly determining their authentic gender identity; and that it is incumbent on everyone else in society to treat them accordingly. But since these acts of self-identification are based on subjective feelings with no associated set of measurable traits or behaviors, the new identities end up being not only ill-defined (especially when it comes to the “non-binary” label) but unstable. Since the only criterion for gender identity is simply, “I am who I say I am,” the associated claims are treated as completely unfalsifiable, no matter how many different “authentic” forms are presented in succession. Even if one concedes that such individuals are acting entirely in good faith, there’s no guarantee that today’s “authentic” self won’t be denounced as tomorrow’s self-deceiving lie.

In this regard, gender ideology is part of a larger movement that some have called expressive individualism, which one academic has defined as the belief that “human beings are defined by their individual psychological core, and that the purpose of life is allowing that core to find social expression in relationships. Anything that challenges it is deemed oppressive.” Consistent with this idea, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has indicated that repression of one’s “true” LGBTQ+ self may lead to depression, anxiety, and suicidality. Under this framework, anything less than complete “affirmation” of a trans-presenting person’s newly asserted gender identity is cast as a vestige of retrograde belief systems—the dismantling of which will supposedly help usher in a new era of authentic (and therefore more healthy and joyful) existence.

As professors of psychology at a religiously affiliated university (full disclosure: with an honor code that embraces traditional Judeo-Christian morality), we have observed growing evidence that many young people now view anything that challenges their expressive individualism as inherently oppressive. Moreover, this is an ideological system that, by its own terms, no one is permitted to debate or critique, since a person’s supposedly “authentic” self is, by definition, coterminous with truth itself.

Until it isn’t: As with Page, the new authentic truth always supersedes the old one. And in some contexts, one even sees such identity shifting embedded in the movement’s typology—as with “genderfluid,” an identity by which one supposedly may take on all sorts of (temporary) gender statuses as part of one’s overarching genderfluid meta-status. (Like many newly coined terms in this area, “genderfluid” comes with a dizzying array of sub-varieties, such as genderfruct, xenofluid, lunagender, quasifluid, cluttergender, parafluid, and agentogender.)

Singer Sam Smith has made serial LGBTQ+ identity transitions in his ongoing—and apparently tireless—search for authenticity. Like Page, Smith first came out as gay in 2014; yet just three-and-a-half years later announced a newly discovered status as “genderqueer.” After two more years living under that ambiguous label, Smith announced a new (and presumably yet more authentic) identity: non-binary, which is to say, neither fully male nor female.

Needless to say, Smith has passionately denounced the gender binary, though this attitude, too, seems to shift unpredictably. In 2021, Smith called for the BRIT music awards to establish gender-neutral categories. The following year, the male and female categories for Best Artist were indeed abandoned, and merged into one all-inclusive Best Artist (which Adele won). This year, however, the nominees do not include any women at all, something Smith now deems a shame—despite the fact that the very idea of binary man-ness and woman-ness is, Smith has informed us, a sort of mirage.

In May of 2021, pop singer Demi Lovato came out as non-binary, adopting “they/them” pronouns and spurning (previously employed) “she/her” pronouns. One year later, Lovato’s pronouns were abruptly updated to “they/them/she/her.” By way of explanation, the singer asserted that she was at the moment “feeling more feminine.”

This brings us back to gender fluidity, which, as already discussed, seems to be defined as a stable form of instability. Dr. Sabra Katz-Wise, a Harvard Medical School pediatrician, recently explained that such apparent contradictions within gender ideology actually make complete sense: “Oftentimes, people might cycle through different gender identities, or different language they’re using or different pronouns, and it doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re not their true selves. It’s just sort of part of this larger gender journey that people are on.”

Of course, this brings us into even stranger territory, since the very idea of a “journey” involves a trip from A to B. And in the idiom of literature and therapy, the word “journey” is commonly used to describe a protagonist’s (or patient’s) quest to achieve positive change. And so use of the word makes no sense in the context of a person hewing to a single “authentic” state. What kind of “journey” involves no movement whatsoever?

In some ways, the ever-expanding system of gender labels and beliefs seems to be offering young people a surrogate for religious faith, since it serves to assure adherents that they are vested with a special essence that makes them unique and authentic, as well as providing them with a like-pronouned tribe of online supporters (or, if you prefer, congregants). As recently as 2011, the Williams Institute at UCLA had been revising the estimated number of LGB individuals in the US population significantly downward. An Institute demographer estimated in 2011 that 1.7 percent of American adults were gay or lesbian and 1.8 percent were bisexual, with a substantial number of other Americans temporarily experimenting (but not identifying) with gay behavior at some point in their lives. Just a decade later, however, we are now talking about a sharp “generational shift” in the growth of the LGBTQ+ population, a shift that (inversely) mirrors the growing rejection of organized religion among youth.

A 2021 Gallup poll found that the (self-described) LGBTQ+ percentage is basically doubling in the United States with each successive generation, starting from a very small share of those born before 1946 (0.8 percent) up through Gen Z (20.8 percent). Although greater societal tolerance of LGBTQ+ identities presumably played a role in this overall increase, it’s hard to believe that this 26-fold increase isn’t an artifact, at least to some extent, of ideology, cultural factors, and social pressures.

Where the end point lies is unknown. Hollywood actor and producer Taika Waititi has suggested that the “+” at the end of LGBTQ+ is so expansive as to subsume literally every human on Earth, stating, “We’re all queer … innately, humans have all got some degree of queerness in them.” One imagines that even some LGBTQ+ activists are wary of such claims, as universal queerdom would remove the distinctiveness of LGBTQ+ self-identifiers (not to mention the publicity dividend paid out when celebrities announce their queer affiliations). So perhaps the movement will burn itself out once being transgender (or its assorted variants) loses its cachet.

In the meantime, however, great damage is being done, because the idea of gender identity as a permanent and innate marker of human identity encourages gender dysphoric children and adolescents to pursue puberty-blocking and sex-change therapies that come with irreversible medical side effects. And a growing number of “detransitioners” are sharing their stories of regret.

Most of these individuals underwent lengthy treatments or surgeries. But each eventually found that transitioning did not bring about the relief they were promised. Now they seek to return to their natal sex, though often with dramatically altered bodies. In many of these cases, an appropriate dose of skepticism from authority figures may have been the right medicine to save them from the consequences of reflexively “affirmative” medical protocols.

Alia (Issa) Ismail is one prominent example of a natal female who elected to medically transition. Her story was captured in the 2018 documentary film, A Year in Transition. At age 16, Ismail came out as lesbian. A few years later, however, she reinterpreted her feelings as evidence of a transgender identity. She describes her initial period of gender transition as a state of euphoria. But two years into her transition, which included a course of testosterone therapy and a double mastectomy, she began to feel increasingly uncomfortable with her altered body. She eventually detransitioned and now prefers to describe her prior feelings as primarily evidence of body dysmorphia rather than gender dysphoria.

For obvious reasons, transgender activists tend to ignore or downplay stories such as Alia’s, preferring instead to insist that unquestioned and immediate gender transition is necessary to avoid pushing trans-identified teens to suicide—a tactic that some might call moral blackmail. To raise objections or pose critical questions in regard to gender ideology, Elliot Page asserts, is to “have blood on your hands.” Yet studies of the long-term results of medical transition do not provide conclusive evidence that it offers a full retreat from suicidality (though, as in Alia’s case, the hopeful claims surrounding transition can provide a temporary respite from anxiety).

We do not know how many transgender individuals will eventually medically detransition, in part because individuals who detransition often simply stop showing up to the gender clinics where such studies are typically conducted, and so the collection of meaningful longitudinal data is difficult. One 2021 study, for instance, found that a majority of 100 studied detransitioners (76 of them) did not inform their original clinicians about their decision. Another recent study, this one of 952 trans-identified adolescents and young adults, found that only about 70 percent of them continued using their prescribed hormones over the course of four years. (Those who began hormones after age 18 had the lowest continuation rate of any cohort, at about 64 percent).

More research is needed to ascertain exactly why young people halt medical transition, and how many choose to restart such regimens. But at any rate, these data suggest that the frequently repeated references to detransition rates as low as one percent are completely unrealistic. As so-called “gender critical” activists have pointed out, much of the research in this area is flawed and unreliable, in many cases because of the strong overlap between trans activists and researchers.

As therapist Sasha Ayad suggests, a less ideological, and arguably more responsible, way to view transgender identity isn’t as an existential state of being, but rather as a descriptor for individuals who deem transition as the best strategy for dealing with dysphoria—i.e., as an instrumental means of coping with a condition, instead of as a grand statement about one’s foundational identity.

Ayad’s position is still seen as heretical among doctrinaire progressives in the United States and other English-speaking countries. But some government actors are beginning to respond to gender-critical concerns. Notably, British officials recently decided to shutter the country’s only youth gender clinic following multiple scandals. The country’s National Health Service has also bluntly noted that many children who say they’re trans are going through a “transient phase.”

As we debate what strategy best helps children to deal with gender-connected anxieties, it should be remembered that the expectation of immediate “affirmation” is only a recent trend. By contrast, the so-called watchful-waiting approach, whereby children are diagnosed and treated holistically to see how their dysphoria develops, has been the primary therapeutic approach for decades—and has helped many youth avoid unnecessary medical interventions. Where the latter approach is concerned, over a dozen longitudinal studies suggest that gender dysphoria is indeed most often a phase that ends once the dysphoric child goes through puberty (though, as noted above, more research is needed).

One problem here is that many parents are bullied, and even gaslit, by educators, therapists, and doctors who’ve been trained to see mothers and fathers as transphobic if they refuse to immediately affirm their child’s claimed trans status—even when the parents suspect that the dysphoria may well be related to trauma, anxiety, bullying, or other mental-health conditions that need to be addressed more urgently. In one recent case reported in the Washington Post, for instance, the mother of a (currently) nonbinary teen asked a parenting coach:

Every professional has admonished and chastised [us] to not even question my daughter’s decisions as to what she is, but to simply accept whatever she offers to us, even though she has insisted she was four different things over the past few months … Is it possible for a teen to identify as something different every month? How much influence do a teen’s friends have on each other to identify? How do we find a therapist, counsellor or pastor who can gently ask questions while respecting that perhaps a 16-year-old doesn’t know everything?

The parenting coach responded flatly: “Your parenting job isn’t to bring them into line; it is to completely love and accept them for exactly who they are (today, this week, next year, etc.).” In other words: accept and affirm, even under the knowledge that such affirmation may lead the child down the road of irreversible therapies that may or may not align with the child’s emerging self-conception in just a few years (or, in this case, weeks). Of course, loving parents may assume that it is always best to validate children’s sincerely felt feelings. But as psychotherapist Seerut Chawla has noted, while one’s feelings may be “true” in the nominal sense of existing, they aren’t the same as “objective reality.”

As an alternative to unmoored subjectivity, many religious adherents have historically found real wisdom in first letting religious teachings define the reality of our existence, and only then seeking to understand how our feelings can mesh over time with that existence. This traditional approach reflects the belief that a stable, communally shared definition of truth is essential for individuals and society to thrive. By contrast, secular perspectives that focus exclusively on living one’s own truth tend to undermine a shared understanding of reality and societal cohesion, since every person is imagined to be living in a self-defined state of being.

It is strange that so little “affirmation” is provided to those whose “journey” causes them to step back from their transitioned identity—including those detransitioners who’ve cited their faith as one such reason for doing so. Many of those who sanctify the authenticity of all LGBTQ+ identities often treat those who abandon such identities with skepticism and disdain. And if Page someday discovers an “authentic” new reality as a detransitioner, you can bet neither Time nor Oprah will have much interest.

That’s because the unstated rule here is that the act of “coming out” suggests that one should never go back in. In this context, gender ideology actually restricts the options available for many individuals seeking to gradually forge a sense of personal identity, by presenting some “authentic” truths as sacred, and others as heretical.

In closing, we say to any who may adopt any LGBTQ+ identity that we do not fear or hate them, nor do we seek in any way to minimize their humanity. Certainly, we do not wish to “erase their existence,” because their existence as human beings is not at issue. We simply remain unconvinced that adopting new gender identities provides a stable foundation for a durable sense of self. Ultimately, a person’s biological sex will remain constant during his or her entire life, no matter how many times he or she picks new pronouns or alters his or her appearance. And an ideology that teaches people to ignore that truth isn’t a promising means for distressed people to find inner peace or fulfillment—much less anything approaching true “authenticity.”