Politics

Beijing in Retreat

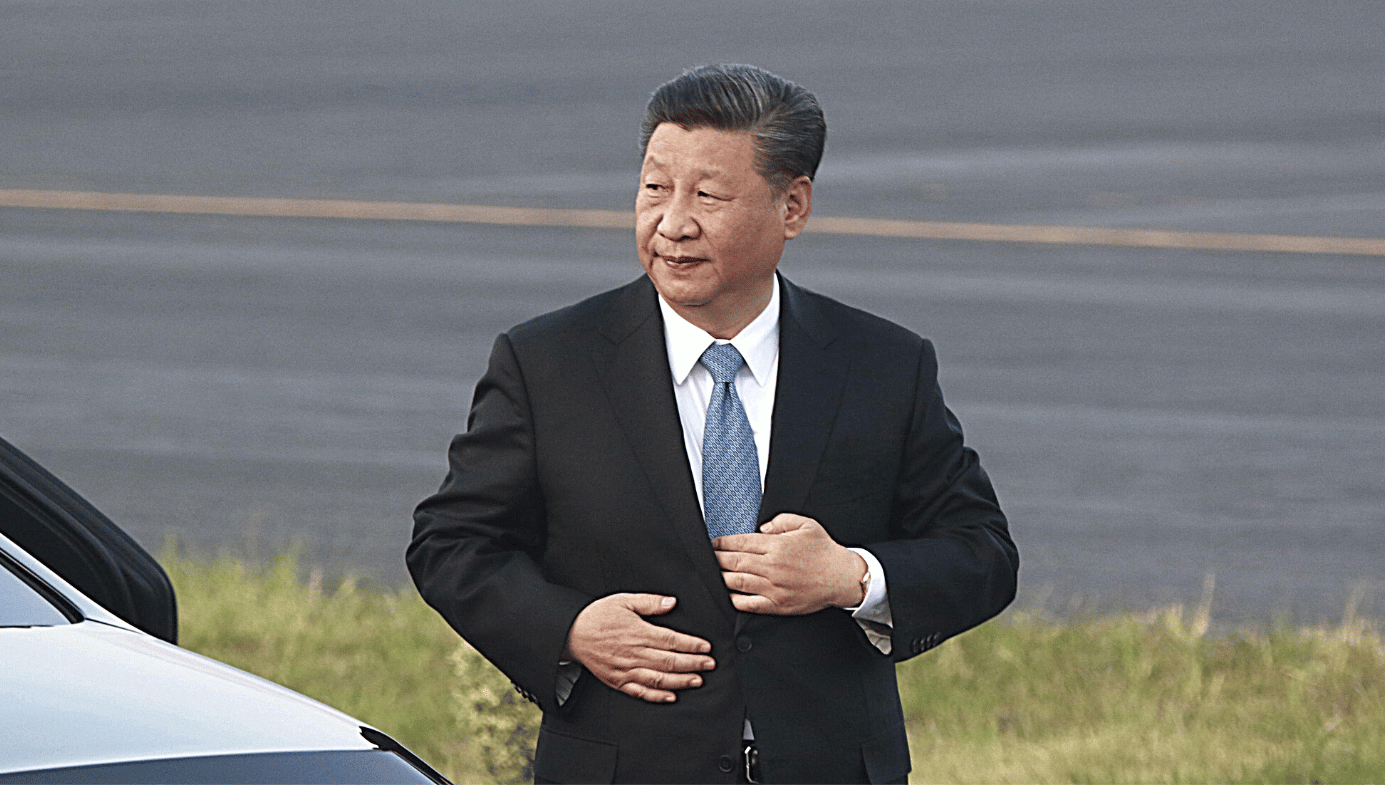

A plunging birthrate, deepening socioeconomic divisions, and the chaos produced by China’s failed Zero-COVID policy prove that Xi Jinping and the Party do not have the measure of the nation.

As China limps out of the COVID-19 pandemic like the last straggler among nations, its ruling Communist Party appears uncharacteristically subdued. The Wolf Warriors have gone quiet; the mood is almost reflective. Beijing has been taking sober stock, realising the vulnerability of its position. Never has the Party faced so many different troubles at once.

On January 17th, authorities admitted that the country’s population has finally begun shrinking, and much earlier than the UN or the CCP had predicted—indeed, much earlier than anyone had predicted, with the exception of the lone prophetic demographer Yi Fuxian. For context, this is the first time that the Chinese populace has declined since 1961, when tens of millions died in history’s worst-ever famine. Today there is no comparable cataclysm; just the slow march of demographic inevitability, set in motion 43 years ago by Deng Xiaoping’s one child policy (the largest social experiment in human history), and moving ever since with the cold certainty of implacable Mother Nature.

The Communist Party actually saw what was happening a full decade ago, but its two-child and three-child remedies floundered. The birthrate continued to drop (more steeply following the new policies), and the trend may have been further exacerbated by Xi Jinping’s “Zero-COVID” policy and its deleterious effect on the nation’s psychology. Nightmare stories circulated, like the report of a pregnant woman who lost her baby due to draconian COVID regulations. She was left bleeding onto the sidewalk in the dead of winter outside a hospital in Xi’an, her child sentenced to death by her expired test result.

These stories proved hard to forget. The Chinese people learned that they can enjoy no certainty about the future and that Xi’s obsession with order leads, paradoxically, to chaos. Young couples realised that if their hypothetical children survived, they would enter a hopeless world of stagnant growth and failing services—a twilight of locked-down apartments and testing booths. Who would bring a child into such a world?

And so the birthrate has plummeted to an all-time low (6.77 births per 1,000 people). Ever paranoid about its international reputation, the Party is likely playing down the true gravity of the situation. But even its own internal data is almost certain to be deficient—the perennial problem of authoritarian regimes. “All of China’s past economic, social, defence, and foreign policies were based on faulty demographic data,” says Yi Fuxian. “China will have to undergo a strategic contraction.” What does that mean in practice? “China will improve relations with the West.”

Sure enough, at the World Economic Forum in Davos earlier this month, Vice Premier Liu He adopted a conciliatory tone. Following several years of growing state control and self-isolation (a trend which began before the pandemic), China will now “let the market play the fundamental role in resources allocation.” Xi Jinping actually made multiple attempts to liberalise the economy during his first five years at the helm (2012–17), but he quickly aborted reforms on each occasion due to a variety of unforeseen complications. In 2023, however, the need has grown more critical. Liu referred to recent “massive blood transfusion to the real estate sector.” As he put it, “China’s national reality means that opening up to the world is a must, not an expediency.” In other words, Beijing urgently requires a return to the status quo—something it always described in the past with the syrupy phrase “win-win globalisation.”

The new air of desperation was first apparent in Xi’s New Year address for 2023, broadcast just weeks after the sudden abandonment of his Zero-COVID policy. “Since COVID-19 struck,” he said, “we have put the people first and put life first all along.” This was nonsense, of course, and offensive nonsense at that. But more importantly, it was a tone never previously heard from the Communist Party: placatory, almost pleading. I detected an odd echo of those famous lines from Richard Nixon’s resignation speech in 1974, about having always tried to do what was best for the nation.

The Party’s changing tenor reflects the sheer volume of problems in China’s immediate future. Take semiconductors: the much-vaunted “oil of the 21st century.” Nanometers in size, thinner than a human hair, tiny computer chips have become indispensable, scattered throughout smartphones, laptops, refrigerators, pacemakers, electric cars, planes, missiles. The Communist Party knows it needs to dominate this industry to have any hope of achieving its lofty global ambitions. Chinese companies, however, cannot build advanced semiconductors, and they cannot build the necessary high-quality chip fabrication rooms. (These are nitrogen-cooled structures, seismically isolated to protect developing microchips from the fatal rumble and tremor of distant motorway traffic.) China’s usual reverse engineering, meanwhile, is out of the question due to the sheer complexity involved.

This leaves the country heavily dependent on American, Korean, and Taiwanese firms. In 2020, China imported some $380 billion-worth of semiconductors (18 percent of its total imports for the year). It’s an uncomfortable position for a would-be world hegemon, and so the Party pumps billions into the domestic industry. The production of advanced semiconductors is now vested with the same priority as the development of the Chinese atomic bomb in decades past. But innovation is eluding the nation’s chipmakers. Despite massive funding, hyped projects in Wuhan and Jinan failed to build a single commercial semiconductor.

Part of this was due to China’s age-old corruption problem. Everyone simply rushed to register their business as semiconductor-related. Restaurant companies, cement-making companies: they all took quick advantage of the vast river of chip money flowing from Beijing. Furious, the Party launched investigations into some executives. Its woes were just beginning. In October 2022, the United States Bureau of Industry and Security announced extraterritorial limits on the export to China of advanced semiconductors, supercomputer components, and chip-making equipment. This will cripple Chinese progress in countless areas: from e-commerce to cybersecurity; from autonomous vehicles to medical imaging. The long-term implications are enormous and the Party knows it.

Then, of course, there is COVID-19. After Xi scrapped Zero-COVID and loosened controls in December, infections soared. Even the CCP’s own statistics suggested that some 250 million citizens were infected in the first 20 days of December. A report part-funded by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention has warned that the nation will suffer a possible death toll of 684 people per million over the coming months. Assuming a Chinese population of 1.4 billion, that’s a total of a million fatalities. The best-case scenario is estimated to be between 448 and 503 people per million, which works out as about 627,000 to 704,000 deaths total. The Economist says it may be as high as 1.5 million.

The result is chaos: the default position of all countries ruled by communist parties. Emergency rooms are running out of beds and oxygen hookups for those suffering respiratory difficulties. “All the doctors are laid up,” a Beijing neurologist told the Financial Times. “We don’t have anywhere to send patients because other departments don’t have enough doctors.” Retired medics are being urged to rejoin the workforce.

Journalist Dake Kang explored the hospitals of Hebei, and found them “buckling.” He saw ambulances turned away; bedless patients on hospital floors. When he visited an ER at Langfang No. 4 People’s Hospital in Bazhou city, the ward was crammed with people on ventilators, while long queues waited for medicine.

1/China is facing a medical emergency. Two harrowing days in Hebei’s ICUs shows the area’s hospitals are buckling with the spread of COVID. We saw ambulances turned away from hospitals, relatives frantically searching for beds, patients sprawled on floorshttps://t.co/Rq1Ov2ejpG

— Dake Kang (@dakekang) December 24, 2022

“There were no beds,” Kang reported, “and doctors were frantically sending critical patients to other hospitals. But even as ambulance after ambulance departed for other wards, car after car with more critical patients came, flooding the hospital.” Footage has emerged purporting to show a Beijing crematorium packed with orange body bags, and in central Hebei, Kang discovered crematoria working overtime to burn vast numbers of bodies.

In time, this wave will pass and normality will resume. But irreparable damage has been inflicted on the Party-people covenant. For three years, COVID-19 was depicted as a “devil virus” and the Zero-COVID policy as a heroic strategy in a “People’s War.” Citizens were urged to fight ceaselessly, and told that the hardships they were suffering proved “the significant advantages of China’s socialist system.” Then suddenly the virus was no big deal, and the very phrase “Zero-COVID” was expunged from propaganda.

Incredibly, China’s population is now expected to simply forget three years of exhaustive testing, snap lockdowns, and brutal quarantine camps. They are expected to overlook the confusing and embarrassing fact that China lost the People’s War, and worse, that the whole effort had been an enormous waste of time and energy. Xi persisted with his policy until the people reached breaking point and could tolerate it no longer. Then, having achieved nothing, he quietly retreated (he has made a habit of such retreats). This has done terrible things to the national psyche. Breakdowns abound. One young man in a BMW ploughed through the crowd at a pedestrian crossing, killing five; another old man shuffled down a hospital corridor with a large stone, crushing patients’ skulls.

Individual tragedies like these mean little to the monolithic Party-state. But it has other concerns about the damage caused by Zero-COVID. Beijing knows that many citizens will refuse to forget the absurd demands made on them for three long years, and it also knows that the White Paper Revolution will set a new precedent. Those protests proved Xi does not have the measure of the nation. He never dreamed that people were so angry. And if he misjudged China back in November, how can he be sure he knows China today or tomorrow?

Gone is the smug certainty of the 20th National Congress in October, when the President cemented his permanent leadership of Party and country, like a mortal ascending to the Godhead. Xi’s New Year address and Liu He’s World Economic Forum comments indicate a hesitancy, a testing of the waters. The CCP wants to reassure itself that it has the love of the Chinese people and the trust of the international community.

Does it? There are some who worship their government-god with such fervour that no number of mistakes and catastrophes will shake their faith. The Party is certainly well-practised in the art of making people forget—after the Tiananmen Square Massacre, sympathetic Premier Zhao Ziyang was effectively erased from history. This was the man who had led China for a decade, overseeing the Reform and Opening Up period. Then suddenly he had never existed. Most modern Chinese do not recognise the name.

But such sleight of hand is unsuited to the age of the Internet; the age of Virtual Private Networks and Chinese studying overseas. These are more cynical times. And Zero-COVID has spent three years repeatedly forcing itself into the life of every Chinese citizen, like a serial abuser. This will be much harder to forget than the existence of a faraway politician like Zhao Ziyang, and a relatively faceless one at that—there was no Xi Jinping-style cult of personality back in the 1980s.

Many citizens have already turned apostate during the pandemic (this section of society made itself suddenly and shockingly known in November’s protests), and many more will be unable to live with the sudden U-turn. The CCP has enjoyed a domestic reputation for competence—a reputation it tries hard to export—and yet the chaos of reopening is incompetence writ large. Everyone can see it. All across this great land, from the fertile Sichuan basin to the northern rustbelt of Heilongjiang, trust is eroding.

At the same time, ominously, we can see the deepening of socioeconomic divisions. Ever mindful of the threat such divisions could pose to the Party, Xi made China’s inequality problem a particular focus in the past. He boasted often that extreme poverty had been “eradicated” during his tenure. But in the early stages of the pandemic, then-Premier Li Keqiang revealed that over 600 million citizens were actually still living on $140 a month or less. China, ostensibly socialist, is one of the most unequal societies on Earth. And in the years since Li Keqiang’s exposure, Zero-COVID has stretched the national gulf wider still.

The “learning gap” has “enlarged,” according to researchers from the Institute for Economic and Social Research at Jinan University. Rural children were forced to study online during the repeated lockdowns—a disaster for their education. When you live in a crowded household where everyone shares a single smartphone or laptop, you will need to wait your turn. This may mean that you take your lesson in the middle of the night. If you are able to study in the daylight, then noise is likely to be an issue. And if the Internet is sketchy where you live, then school begins to resemble a farce.

“We are teaching easier maths now than prior to the pandemic,” says a maths teacher at a middle school in Qujing, a small town in China’s deep south. “What a mess!” And parents in those poorer areas can hardly afford to stay home to help out. “Students from better-off families have done better,” she says, “especially when parents are around to help them study.” For the less fortunate, online lessons have been worse than useless. The effect on social mobility will be devastating.

It has to be assumed that the authorities are at least dimly aware of these developments. Hundreds of millions of Chinese do not recognise the prosperous and showy China that the CCP promotes to the world; the China of sprawling megalopolises and the affluent eastern seaboard. That is not the world they live in—it is in effect a completely different nation and their resentment is rising.

Beijing will struggle to conquer each of these troubles, in particular the country’s great demographic death-sentence. Inevitably, the Party will resort to force, the only thing it really understands. From forced abortions to forced births. Such a strange policy would actually have precedent in the global Communist Party’s hundred-year war with human nature. Nicolae Ceaușescu outlawed contraception for Romanian women in the 1960s. He banned abortion and monitored menstrual periods, so the authorities would know when a woman should be doing her duty and trying for a baby. Those who failed to get pregnant were questioned by police. “The fetus is the property of the entire society,” said Ceaușescu. The CCP certainly believes as much. But enforcing such a policy on a billion-strong nation—most of whom are now reluctant and cynical when it comes to the childbirth issue—would be a hopeless task.

And so, fearful of perils within and without, the Party comes to us now in its latest guise, with a fawning smile and cap-in-hand. We should not be fooled. These are the snide tactics of yesteryear—the tactics of Jiang Zemin in the 1990s and Hu Jintao in the 2000s, when they followed Deng Xiaoping’s advice to “hide your strength and bide your time.” Beijing needs a period of recuperation, a time to nurse its wounds and slowly build up power.

We risk falling for the same act once again. The State Administration of Foreign Exchange has already said that it expects “steady and continuous” foreign capital inflows this year. Many in the West will be eager to re-engage with the China they remember from a decade ago (back in the so-called “golden era”). We need to remember that this is the Party of genocide and ruthless global ambition, as unmasked so dramatically in recent years. Weakened but unchanged. Xi may have abandoned Zero-COVID in line with the wishes of the Chinese people, but he has also begun rounding up protesters. One by one, they are disappearing from their homes.

And we should keep another danger in mind. The CCP’s diminishing status in the eyes of the Chinese nation may drive it to finally make a move for Taiwan, trusting in the unifying power of nationalist war-lust. This would certainly provide an outlet for the country’s volatile droves of angry young men, doomed to singledom by the nation’s chronic sex imbalance (yet another legacy of Deng Xiaoping’s one-child policy). And it would be a most useful distraction from the average citizen’s mounting woes. The Party could even solve its semiconductor problem by seizing control of the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) in Hsinchu city—the world’s best.

Of course, if the resulting chaos caused production to stop at TSMC, the impact on the global electronics industry would be enormous, and the Chinese people would suffer as much as anyone else. This would provide an effective deterrent to a rational actor. But is Xi a rational actor? We might gain insight from his own speeches to CCP leaders. In 2021, he spoke admiringly of his beloved Mao Zedong, who showed “determination and bravery” because he was willing “to ruin the country internally in order to build it anew.” This is the real Xi Jinping. For all that talk about “put[ting] the people first,” he has only ever put the Communist Party first, and its hypernationalist agenda.

In the short term, at least, we can hope that the CCP’s newfound desire to ingratiate itself will forestall an invasion. Now is the time for Western governments to be more bullish and commit publicly to defending Taiwan, emphasising that an invasion would ruin the Chinese government more decisively than it would ruin China. And if relationships thaw and we enter a new era, they should never forget the true nature of this Communist Party.