Art and Culture

Scenes from a Marriage

In 2020, a British High Court judge ruled that actor Johnny Depp was probably a “wife beater.” Earlier this year, an American jury disagreed. Who got it right?

I.

On December 19th, 2022, 36-year-old actress Amber Heard used an Instagram post to announce that she would not be appealing the outcome of a defamation suit won by her ex-husband, the 59-year-old Pirates of the Caribbean star Johnny Depp. The basis of that suit had been an op-ed Heard had published in the Washington Post on December 18th, 2018, beneath the headline, “I Spoke Up against Sexual Violence—and Faced Our Culture’s Wrath. That Has to Change.” In that article, Heard had described herself as a “public figure representing domestic abuse” (presumably by Depp) and stated that “I had the rare vantage point of seeing, in real time, how institutions protect men accused of abuse.”

On June 1st, 2022, following a two-month trial, a jury of five men and two women in Fairfax County, Virginia, unanimously awarded Depp $15 million in damages, $10 million of which was awarded as compensation. An additional $5 million in punitive damages, arrived at over 13 hours of deliberation, resulted from their finding that Heard had acted with “actual malice.” The trial judge, Penney Azcarate, reduced the total to $10.3 million under a Virginia tort-reform law that caps punitive-damage awards at $350,000.

The jury also found that Depp—or, more specifically, one of his former lawyers, Adam Waldman—had defamed Heard in statements to the Daily Mail in 2020. Waldman accused her of confecting evidence to support her allegation of a violent confrontation with Depp at his penthouse at the Eastern Columbia Building in downtown Los Angeles on May 21st, 2016. Heard filed for divorce two days after that incident, on May 23rd. “The officers came to the penthouses, thoroughly searched and interviewed, and left after seeing no damage to face or property,” Waldman told the Mail. “So Amber and her friends spilled a little wine and roughed the place up, got their stories straight under the direction of a lawyer and publicist, and then placed a second call to 911.” Heard’s victory on this counterclaim yielded her $2 million in damages—a token amount that left her owing Depp more than $8 million.

Heard’s lawyers filed an appeal on November 23rd, but less than a month later, she declared the matter settled. Her insurance company would pay Depp a mere $1 million and that would end all the litigation. “I finally have an opportunity to emancipate myself from something I attempted to leave over six years ago and on terms I can agree to,” she wrote in her Instagram statement. “I have made no admission, this is not an act of concession. There are no restrictions or gags with respect to my voice moving forward.”

The trial in Virginia was the second of two suits brought by Depp over his alleged mistreatment of Heard. The first, in November 2020 (which he lost), was against a British tabloid that had described him as a “wife beater.” These two trials, Heard complained, had produced a social-media campaign of “vilification” that exposed her to “a type of humiliation” she could not bear to re-experience. “Even if my US appeal is successful,” she wrote, “the best outcome would be a re-trial where a new jury would have to consider the evidence again. I simply cannot go through that for a third time.”

II.

The June verdict in Virginia shocked and appalled feminists in the media and nearly everywhere else. About five years had elapsed since New Yorker writer Ronan Farrow precipitated the #MeToo social-media movement with his lurid reports of sexual exploitation by Oscar-winning Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein over a three-decade career. In February 2020, a New York jury convicted Weinstein of five criminal charges, including rape and sexual assault, and he was sentenced to 23 years in prison. On December 19th, a jury in Los Angeles returned a mixed verdict, convicting Weinstein on one rape charge, acquitting him on another, and failing to reach a verdict on three further counts.

The Weinstein reports generated a flurry of activism and a rapidly expanding definition of sexual misconduct that grew to encompass assault, professional quid pro quos, clumsy advances, and finally, bad sex on bad dates. Accusations of various kinds of untoward behavior were made against a number of professional men, colleagues of both sexes scrambled to condemn them, and employers frequently moved to fire the accused with extreme alacrity. Reputations and careers in journalism and the arts went up in smoke in the blink of an eye, and a crowd-sourced list of “Shitty Media Men” was compiled and circulated on the basis of unsubstantiated allegations.

This first wave of accusations and professional defenestrations crested in January 2018, when an anonymous young woman using the pseudonym “Grace” gave an interview to the now-defunct Babe website in which she accused Parks and Recreation star Aziz Ansari of assaulting her on a date. Ansari had invited her to dinner and then back to his apartment, where she became “uncomfortable” after a bout of consensual oral sex, and fled home in an Uber. When HLN host Ashleigh Banfield, then-New York Times journalist Bari Weiss, and the Atlantic’s Caitlin Flanagan all excoriated Ansari’s accusers, it seemed to drain the #MeToo movement of its once-unstoppable momentum, at least for a while. But it has revived itself spasmodically in the months and years since.

In September 2018, the Senate held its confirmation hearing for Donald Trump’s Supreme Court appointee Brett Kavanaugh. A surprise witness, Christine Blasey Ford, who had grown up in Kavanaugh’s home town of Bethesda, Maryland, and become a clinical psychologist, testified that he had sexually assaulted her at a drunken high-school party during the early 1980s. Kavanaugh vehemently denied that the incident had occurred, or that he remembered ever having met Blasey Ford, and the Republican-led Senate voted to confirm him. Nevertheless, her allegations outraged those who believed her, and Kavanaugh became a synecdoche for the kind of wanton abuse that men routinely inflict upon helpless females unless checked by law and public opinion.

It was out of this primordial soup that Heard’s Washington Post op-ed emerged on December 18th, 2018. Heard was then at the peak of her Hollywood fame as the co-star and cinematic love-interest of Jason Momoa’s eponymous hero in Aquaman. The film officially opened in the US on December 21st, 2018, but a blockbuster premiere in London on October 16th had presaged its commensurate success Stateside. It eventually raked in $1.5 billion worldwide, and became the fifth-highest grossing film of 2018.

Heard’s op-ed was a carefully worded document, and had, it would later transpire, been extensively vetted (and possibly ghost-written) by staffers at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Her divorce settlement with Depp, filed in the Superior Court of Los Angeles County on August 26th, 2016, had included a $7 million cash payment by Depp that she had pledged to donate entirely to charity: $3.5 million was supposed to go to the ACLU and $3.5 million would go to the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. Heard’s self-description as a “public figure representing domestic abuse” yielded the obvious inference that she had been a victim of Johnny Depp’s mistreatment, even though she did not make this allegation explicit. To have done so would have violated the terms of the couple’s divorce settlement, in which both former spouses had pledged not to disclose any aspect of their marriage, including incidents of violence.

On May 27th, 2016, four days after Heard filed for divorce, she had returned to court and obtained a temporary restraining order (TRO) barring Depp from approaching or stalking her (even though, by this time, Depp was in New York preparing for a European tour with his band, Hollywood Vampires). Her divorce filing had demanded that Depp pay her $50,000 a month in spousal support among other recompense, generating a claim by Depp’s lawyers, including Waldman, that Heard had been trying to “secure a premature financial resolution [of her divorce demands] by alleging abuse.”

The couple’s final settlement agreement formally terminating the marriage in 2017 had ostensibly buried all those claims under a silt layer of goodwill that, among other things, dissolved the TRO and its attendant allegations. “Our relationship,” the pair had declared in a joint statement, “was intensely passionate and at times volatile, but always bound by love. There was never any intent of physical or emotional harm.” Heard, according to her own account, had walked away from her marriage to Depp with nothing monetary to show for it beyond his promise to settle her litigation bills.

III.

Everyone who followed the Depps’ brief excursion into matrimony suspected that there was more to the union than the unconvincing declaration that it was “always bound by love.” The tabloid website TMZ had been tipped off about Heard’s TRO filing, and she walked out of the courtroom into a sea of paparazzi who snapped pictures of her with a bruise on her right cheek. The site also obtained a photograph showing Heard’s bruised face, allegedly caused by Depp striking her with his cell phone.

On June 13th, 2016, an issue of People magazine carried even more photos, including an “exclusive” cover photo taken by a “friend” of Heard (People’s language) showing an apparently lacerated right eye, a swollen cheek, and a cut lip. “Inside Their Toxic Marriage,” the cover line blared. The People article quoted an affidavit Heard had filed in support of her restraining-order request, in which she averred that Depp had “been verbally and physically abusive” to her, typically while under the influence of drugs and alcohol, throughout the “entirety” of their four-year relationship.

Heard’s affidavit alleged three specific incidents. First, during a violent argument on December 15th, 2015, she said that Depp had thrown a decanter at her, slapped her, punched her, head-butted her face, pulled out chunks of her hair, and pushed her onto their marital bed with such force that the bed frame collapsed. Second, at her 30th birthday party on April 21st, 2016, she said Depp had arrived two hours late “inebriated and high,” grabbed her by the hair, and shoved her to the floor. Third, on May 21st, 2016, Depp had allegedly hurled a cell phone into her face, “striking my cheek and eye with great force,” behavior that led to a 911 call and the arrival of the police. A separate statement filed by Heard’s then-best friend and adjoining-penthouse neighbor, sometime yoga instructor and jewelry designer Raquel “Rocky” Pennington (not the MMA fighter with the same name), alleged that Depp had swung a magnum-size bottle of wine in Heard’s direction that evening and smashed it against a door.

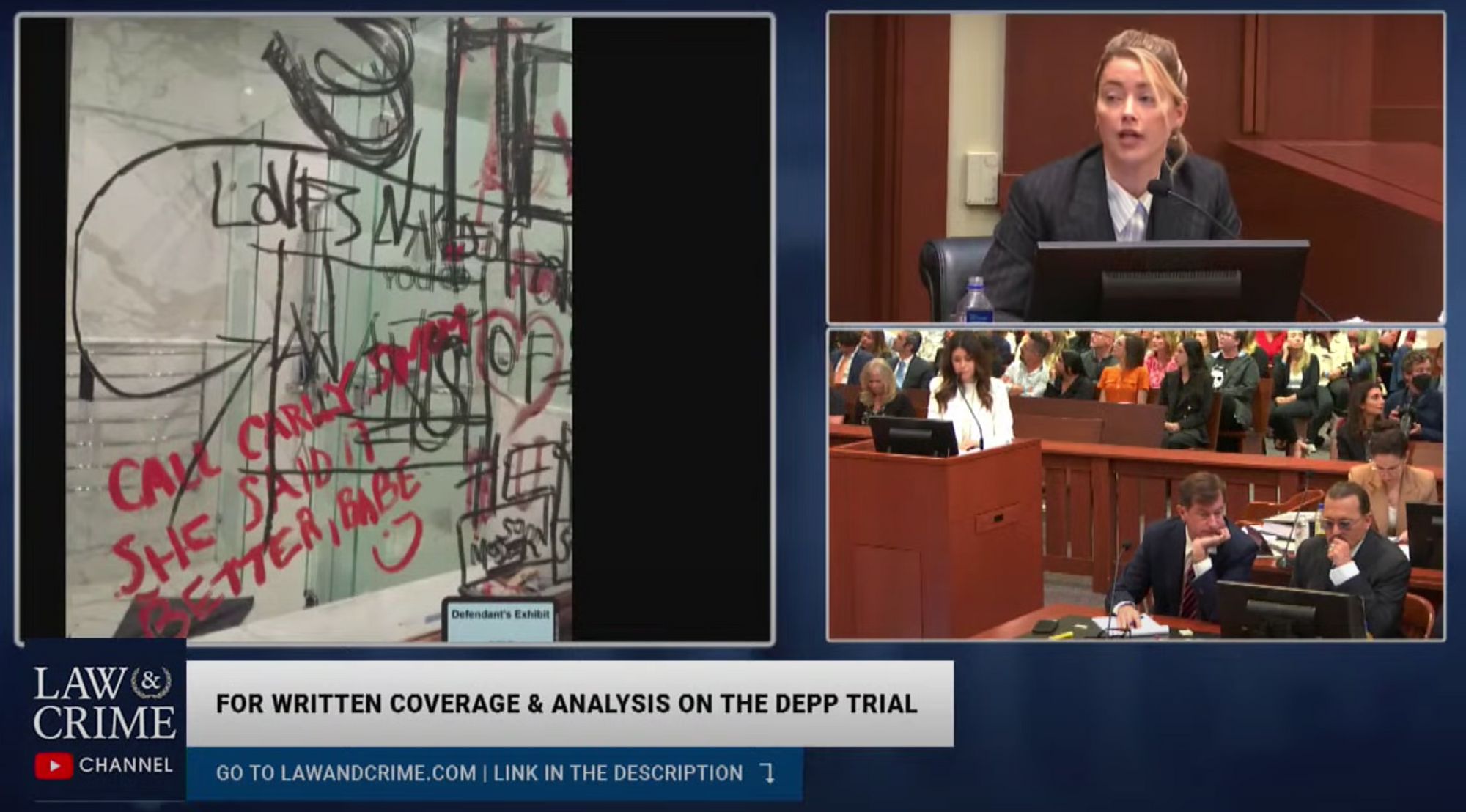

Other incidents alleged in Heard’s divorce-court documents and afterwards were equally hair-raising. Heard’s affidavit described a bloody weekend-long, alcohol-infused rage-fest in March 2015. This was just a month after the couple’s wedding, and they were in Australia at the time while Depp filmed a fifth installment of Pirates of the Caribbean (released in 2017). Heard said that Depp, addled with liquor and drugs during a three-day binge, and furious that she was refusing to sign a postnuptial property-allocation agreement (there had been no prenup), had severed the tip of the third finger of his right hand by smashing it into a wall phone. He had then thrown her onto a counter and held her down while he sexually penetrated her with a vodka bottle, before writing her name (“Easy Amber”) on a mirror in his own blood and black paint, along with the praenomina of Billy Bob Thornton, her costar in the 2018 film London Fields, with whom Depp suspected she had slept. (Depp admitted at trial that he had scrawled all of the insults except for a scribble in red lipstick—“Call Carly Simon she said it better, babe”—which he attributed to her. He also denied the sexual assault and maintained that it had been Heard who had severed his finger by throwing a vodka bottle at his hand as it rested against the bar where he had been drinking at their rented house.)

In a June 8th, 2016, article for Refinery 29, iO Tillett Wright, a transgender-male photographer/writer friend of Heard’s who looks like a Jet from the original West Side Story, admitted that he had been the one to phone the police (from New York City after hearing Heard screaming down the phone to him from Los Angeles) on May 21st, 2016. “I called 911 because she never would,” he wrote. Tillett Wright didn’t identify Heard or Depp in his account, but the references could not have been more pointed. The article rambled melodramatically through alleged incidents that later surfaced in Heard’s testimony during the Depp-Heard litigation: an episode in May 2014 when a drunken Depp supposedly kicked Heard to the floor on a private-plane ride from Boston to Los Angeles (Depp maintained at trial that he had actually spent the flight locked in the plane’s bathroom to avoid Heard’s torrents of verbal abuse), and the incident on December 15th, 2015, when Depp had allegedly head-butted her and pulled out her hair. Tillett Wright wrote that he had personally seen the clumps of blonde hair on the floor shortly after the assault. He also described Depp as terrorizing Heard’s younger sister, Whitney Henriquez, who lived in an adjacent Eastern Columbia penthouse.

On August 12th, 2016, the day before Heard sat for a deposition in her divorce case, TMZ, which was covering the Depp-Heard breakup with its usual relish, published an undated video clip, apparently leaked from Heard’s phone, in which Depp thrashes recklessly around the kitchen of a castle-style 1920s mansion he owned on Sweetzer Avenue in West Hollywood. Clad in a denim jacket, aviator sunglasses, and a cowboy hat—an unusual ensemble for the early hours of the morning—Depp kicks the fridge, slams various cabinet doors that get in his way, pours a pint of red wine into a “redneck wine glass” (a Mason jar fused to a goblet stem) for his breakfast, and lunges toward Heard.

“You want to see crazy,” Depp yells, “I’ll show you fucking crazy!” The TMZ “kitchen video,” as it came to be known, has been watched by nearly 10 million people on YouTube since a slightly longer, apparently unedited version of it was shown during the trial on April 22nd, 2022. It would become the single most memorable record to emerge from those proceedings.

On April 27th, 2018, during the brief lull in #MeToo activity between the Aziz Ansari accusation in January and the Kavanaugh hearing in September, Dan Wootton, then the executive editor of British tabloid the Sun, decided to excoriate Harry Potter-creator J.K. Rowling in his paper. The headline that originally appeared above Wootton’s article read: “How can JK Rowling be ‘genuinely happy’ casting wife beater Johnny Depp in the new Fantastic Beasts film?” By the following day, the phrase “wife beater” had been removed from the website and it did not appear in the print version of the article. Nonetheless, on June 1st, 2018, Depp’s lawyers filed a lawsuit for libel against Wootton and Rupert Murdoch’s News Group Newspapers.

Heard’s Washington Post op-ed was published a little over six months later. It is vanishingly unlikely that anyone reading it would have failed to associate her reference to “domestic abuse” with her divorce-court affidavits against Depp and the TRO, the TMZ and People photos that purported to document her injuries, Tillett Wright’s Refinery 29 article, the TMZ kitchen video, Wootton’s Sun screed, and Depp’s subsequent libel suit. Unflattering in-depth interviews with Depp in Rolling Stone and GQ, published on June 21st and October 2nd of 2018 respectively, had pushed the couple’s brief but explosive marriage up the celebrity gossip agenda, along with stories of Depp’s copious drug and alcohol consumption and the profligate spending that had reduced him to near-bankruptcy. (His wine bill alone totaled $30,000 a month.)

“Two years ago,” Heard wrote in the Post, “I became a public spokesman representing domestic abuse”—a timeframe that implicitly connected her new role to the allegations swirling around Depp and the #MeToo movement itself. Heard complained that she had been dropped as the advertising face of a “global fashion brand” (identified by amateur sleuths as the Italian luxury-shoe manufacturer Tod’s), and that there had been “questions raised” about her reprising her role in Aquaman. “I felt the full force of our culture’s wrath for women who speak out,” she wrote of these career setbacks. “I had the rare vantage point of seeing, in real time, how institutions protect men accused of abuse.” (Her part in the sequel, Aquaman and the Lost Kingdom, scheduled for release in 2023, was indeed severely reduced; a spokesman for its distributor, Warner Brothers, testified in a deposition for the Depp-Heard lawsuit that this was due to a lack of onscreen “chemistry” between her and Momoa.)

Four days after Heard’s op-ed appeared, according to reports, Disney dropped Depp from a planned sixth episode of Pirates of the Caribbean. According to testimony at the Depp-Heard trial, that role would have netted him $22 million. Depp’s 17th-century character—the swashbuckling and elaborately costumed, tattooed, and makeup-enhanced Captain Jack Sparrow—was the reason audiences had flocked to the five previous Pirates movies, and the role had earned him a reported total of $300 million over the years. And so, in March 2019, as he was preparing to go to trial in London, Depp sued his ex-wife for defamation, too.

IV.

Following delays caused by the coronavirus pandemic, Johnny Depp’s libel suit against News Group Newspapers and the Sun’s executive editor Dan Wootton finally got underway in London’s High Court of Justice on July 7th, 2020, and lasted for three weeks. Although Heard appeared as a witness and not a defendant, the Sun lawsuit was essentially a dress rehearsal for the Depp-Heard trial that would be held in Virginia two years later. Heard gave evidence of being victimized by Depp, something she would also do in the Virginia proceedings, and most of the same allegations were hashed out by a nearly identical cast of characters. There was an important difference, however. Most English civil cases are now bench trials conducted in the absence of a jury, so it was presiding Justice Andrew Nicol’s job to determine the verdict, which he duly delivered on November 2nd, 2020.

Nicol’s findings were devastating for Depp. By this point, Heard was alleging not three but 14 specific incidents from 2013 to 2016 in which Depp had allegedly been violent towards her. These included kicks, blows, pulled hair, the alleged rape with the vodka bottle, and the head-butting, hair-pulling incident in 2015. There was also an earlier incident in 2013 in which Heard said Depp had performed a nonconsensual cavity search on her in a trailer during a frenzied quest for cocaine; a slapping and punching attack in the couple’s New York City hotel room after the Met Gala in 2014 that Heard said she thought had broken her nose and given her two black eyes (she said that Depp suspected her of sleeping with James Franco, who had costarred with her in the 2008 movie Pineapple Express); another sexual assault in the Bahamas over Christmas 2015, and numerous hurled glasses and liquor containers besides the cell phone.

Nicol found in the Sun’s favor on 12 of those counts, a judgement that rested almost entirely on his willingness to accept Heard’s testimony. A party’s burden of proof—the standard he must satisfy in order to legally prove a fact in court—is far lower in a trial involving a civil tort such as defamation than it is in a criminal trial, where the prosecution must prove its case “beyond a reasonable doubt.” In civil cases, the standard is simply a “preponderance of the evidence” (or “preponderance of probabilities” in the UK)—that it is more likely than not that an incident occurred.

For Nicol, the delicate pan balance of the preponderance standard almost invariably tipped the scales toward Heard. This included a finding that Depp, contra his trial testimony, had indeed accidentally sliced off his own finger (as he had told emergency-room medics afterwards, although he maintained at trial that he had lied in order to protect Heard and himself from a vulturous press), raped his then-wife with the vodka bottle, and bashed her and pulled her hair out on numerous occasions. Nicol found supportive evidence in jocular texts that Depp had sent his friends fantasizing violence against Heard whenever the two were at odds. For example, Depp had texted his actor-friend (and alleged companion in massive drug-consumption) Paul Bettany on June 11th, 2013: “Let’s burn Amber!!!... Let’s drown her before we burn her!!! I will fuck her burnt corpse afterwards to make sure she’s dead.” Nicol evidently did not share or appreciate Depp’s macabre sense of humor.

Nicol also resolved in Heard’s favor several issues that Depp’s lawyers had raised relating to her credibility and trustworthiness. For example, after the disastrous April 21st, 2016, birthday party, Depp had stormed out of the penthouse to his Sweetzer Avenue castle, and Heard had headed off with friends to the Coachella Music Festival, an annual Mojave Desert blowout that has become a celebrity magnet. Depp’s housekeeper arrived at the penthouse the next morning to clean up the mess, and reported to Depp that she had found what appeared to be human feces on the bedsheets. She sent him a photo. Depp stated that he believed that either Heard or one of her friends had been responsible, while Heard maintained that one of the couple’s two pet teacup Yorkshire terriers, Pistol and Boo, was the likely culprit. The evidence wasn’t exactly equivocal: Depp’s chauffeur, Starling Jenkins II, who had driven Heard to Coachella and back after the blowup, testified that Heard had told him on the drive that she had left a “surprise” in Depp’s bed. Nonetheless, Nicol wrote in his judgement:

In my view, whether Ms Heard or one of her friends was in fact responsible is not important. It is remote from the central issue, namely whether Mr Depp assaulted Ms Heard. It is not even of significant relevance to whether Ms Heard assaulted Mr Depp. For what it is worth, I consider that it is unlikely that Ms Heard or one of her friends was responsible. Mr Depp had left that night for his property in Sweetzer. As long as he was away, it was Ms Heard who was likely to suffer from the faeces on the bed, not him. It was, therefore, a singularly ineffective means for Ms Heard or one of her friends to “get back” at Mr Depp. Other evidence in the case showed that Boo (one of the two dogs) had an incomplete mastery of her bowels after she had accidentally consumed some marijuana.

Nicol similarly dismissed as irrelevant an incident in April 2015, when the couple was caught smuggling the two Yorkies into Australia during another round of filming for Pirates 5. (The dogs were confiscated, then hastily shipped back to California in lieu of euthanasia.) Besides allegedly lying about the animals’ presence in their luggage, Heard, according to oral and written testimony, had allegedly tried to persuade her assistant, Kate James (whom she let go later in 2015), and others on this and previous occasions to falsify documents stipulating that the dogs had received their required veterinary shots in timely fashion (“grease” a veterinarian was a word that James said Heard had used regarding an alleged smuggling of the dogs into the Bahamas in 2013).

In April 2016, Heard had pleaded guilty to failing to declare the dogs, expressed remorse and confusion, and been let off with a month’s probation. Nicol ruled that it was not Heard but Depp who had needed the Australian government’s approval for future filming trips there, and that it was he who had stood to benefit from not being held personally responsible for importing the dogs. It had therefore been the responsibility of Depp’s staff, not Heard or her staff, to complete the necessary paperwork truthfully. “Whether or not the suggestion of ‘greasing’ a vet originated with Mr Depp,” Nicol concluded, “I take Ms Heard’s denial that it originated with her as final. This does not, therefore, impinge on her credibility.”

He also waved away an allegation made by Depp’s legal team that Heard had lied to the Department of Homeland Security (which enforces US immigration law) in September 2014 when asked if she had illegally employed a British citizen, Savannah McMillen, as an assistant in the US and written her at least one check for $1,625. Heard maintained that McMillen had simply been a friend in need of cash who ran an occasional errand for her as a favor. “I accept Ms Heard’s evidence in this regard,” Nicol wrote. “I do not consider the letter to Homeland Security was a lie.”

Nicol’s November 2020 judgement in the Sun case ran to 129 pages, and it was couched in such measured and dispassionate language that many observers assumed that Depp had not a chance of winning his US defamation suit against Heard when it came to trial on April 11th, 2022. Under British libel law, it is the defendant, not the plaintiff, who has the burden of proving his case—which means that it tends to be difficult for a British plaintiff to lose. Yet Depp had lost ignominiously (he was ordered to pay the Sun’s legal costs and attorney’s fees). The Sun’s headline-writers gloated by calling him a “wife beater” for days afterwards.

But there was a wrinkle in the case that many observers failed to notice as press attention moved elsewhere. During the trial, Heard had testified under oath that her entire $7 million divorce settlement had been “donated” to the two nonprofits she had designated. This testimony had made an impression on Nicol, who had stated in his opinion that Heard’s “donation of the $7 million to charity is hardly the act one would expect of a gold-digger.” But in late 2020, Depp’s lawyers discovered that she had actually handed over only $350,000 to the ACLU and nothing at all to the Children’s Hospital. Depp himself had donated $100,000 to each organization in 2016, before the couple’s divorce had been finalized. In 2017, Elon Musk, who started dating Heard after she filed for divorce, used funds he controlled to make a donation in Heard’s name of $250,000 to the ACLU, and another to Art of Elysium, an art-therapy nonprofit where Heard’s sister Whitney was employed, which works with several Southern California hospitals, including Children’s.

Depp’s lawyers hoped that this new evidence suggesting Heard had been less than truthful on the stand might warrant a new trial, and so they filed an appeal. But on May 25th, 2021, the UK appeals court denied their request and affirmed Nicol’s findings. The notion that Nicol had been swayed by Heard’s claimed giveaway, ruled the appeals-court judges, was “pure speculation, and in our view very unlikely.” Depp’s humiliation appeared to be complete. As far as casual observers were concerned, he had been called a wife beater by a British newspaper, he had sued in a jurisdiction notoriously friendly to plaintiffs, lost, and his appeal had been thrown out. His chances of winning a second round in the land of the First Amendment were therefore presumed to be zero.

But those who had been paying attention to the small print were less sure. The appeals court ruling notwithstanding, Heard appeared to have perjured herself and this did not speak well of her credibility as a witness or as a person. Which left an interesting question: would an American jury of Heard’s peers indulge her with the same generous benefit of the doubt bestowed upon her by a British establishment judge? The answer turned out to be a very definite “No.”

V.

When the Virginia jury found in Depp’s favor on June 1st, 2022, and awarded him swingeing damages, the legacy media recoiled in horror. Hadn’t the facts of this matter already been established? And hadn’t Heard wept repeatedly on the witness stand as she detailed the blows, kicks, and sexual violations that Depp had allegedly dealt her? The outrage of feminists was incandescent. New York Times columnist Michelle Goldberg was among the first to ventilate on June 2nd, the day after the verdict: “The repercussions of this case will reach far beyond Heard,” she prophesied grimly. “All victims of domestic or sexual abuse must now contend with the possibility that, should they decide to tell their story publicly, they could end up bankrupted by their abusers.”

On May 18th, while the verdict was still pending, Goldberg had written another New York Times column titled, “Amber Heard and the Death of #MeToo.” She faulted Azcarate, the presiding judge, for allowing the trial to be televised. That decision had brought massive daily audiences to CourtTV on cable and to the free livestream on the Law&Crime YouTube channel. Much of the round-the-clock commentary on Twitter, TikTok, and other social-media platforms that resulted, Goldberg noted, was openly hostile to Heard:

Online, there is a level of industrial-scale bullying directed at Heard that puts all previous social media pile-ons to shame. Countless videos skewer Heard on TikTok; NSYNC member Lance Bass joined in the trend of mockingly reenacting her testimony. A makeup brand [Milani Cosmetics] even took part in the anti-Heard melee, posting a TikTok video meant to contradict her lawyer’s description of how she covered up bruises [Milani maintained that it didn’t start manufacturing the particular concealer that Heard’s lawyers displayed in court until 2017, a year after Heard’s divorce filing]. Meanwhile, every platform appears to be full of adoring pro-Depp memes. “Why Does It Seem Like the Entire Internet Is Team Johnny Depp?” said a Vice headline.

But it is not just the internet. “Believe all women, except Amber Heard,” Chris Rock joked recently. A “Saturday Night Live” sketch last weekend turned one of Depp’s wildest accusations against Heard [the bed defecation] into a skit, treating her as a figure of ridicule and him as a charming scamp.

On June 17th, Goldberg appeared on NBC’s Dateline to blame the general lack of audience sympathy for Heard on a contemporary American culture permeated with “misogyny.” Moira Donegan, the feminist who had started the Shitty Media Men list, echoed Goldberg in the pages of the Guardian:

The trial has turned into a public orgy of misogyny. While most of the vitriol is nominally directed at Heard, it is hard to shake the feeling that really, it is directed at all women—and in particular, at those of us who spoke out about gendered abuse and sexual violence during the height of the #MeToo movement. We are in a moment of virulent antifeminist backlash, and the modest gains that were made in that era are being retracted with a gleeful display of victim-blaming at a massive scale.

Atlantic contributor Megan Garber averred that the jokes and jibes “have demeaned not just Amber Heard, but also those who see in the trial’s allegations shades of their own experiences. Survivors watch and learn. They see the emoji that cackle across the livestreams. They see the memes. They register the lols. They watch as a culture that can’t tell the difference between horror and humor has, and makes, its fun.”

The most bitter critic of all was Charlotte Proudman, a British barrister specializing in cases of abuse against women and a fellow at Cambridge University. “This one hurts like an open wound,” she wrote of the verdict in a June 2nd op-ed for the Washington Post:

We saw tired, misogynistic methods used again and again to discredit a woman trying to stand up for her rights. Blaming Heard for not leaving, for fighting back, for not being bruised enough, for not having enough evidence. And when she did have evidence? Depp’s team portrayed her as a manipulative liar—and the jury appears to have found this credible.

In an article for the Independent, Proudman wrote: “[W]hen I see hashtags like “AmberHeardIsALiar,” I realize how deeply entrenched misogyny is in our society … our patriarchal society is sustaining this and using Depp to continue the empathy toward the perpetrators and the admonishment of victims.” She continued her defense of Heard throughout the summer and fall on Twitter, Instagram, and elsewhere. By late October, she was warning followers of her Twitter feed against dressing up as either Depp or Heard for Halloween: “If you do, it’s very clear where you stand on domestic violence.” (Depp’s Jack Sparrow character turned out to be one of Halloween 2022’s most popular male costumes.)

There have been no official allegations—by Heard’s lawyers or anyone else—that the Virginia jury was actually tainted by unauthorized out-of-court exposure to social media hostile to Heard. Azcarate specifically instructed the jurors not to follow the case on any media, and struck the testimony of a witness for Depp who had done so. Nevertheless, it became an unshakeable article of faith among feminist journalists that TikTok, Twitter, and YouTube had singlehandedly destroyed Heard’s credibility and her case. Not only that, but social media had made it impossible for any other woman to accuse a former partner of abuse and win in court.

On May 26th, New York Times columnist Amanda Hess wrote: “When the trial ends this week, the elaborate grassroots campaign to smear a woman will remain, now with a plugged-in support base and a field-tested harassment playbook.” New Yorker writer Jessica Winter agreed: “This is who [Heard] is now—the victim of an unprecedented Internet pile-on, a bruised face on an iPhone, a woman who makes people laugh when she cries.”

On July 13th, Azcarate lifted a seal that had hitherto protected the documents filed in court by the parties before the trial—deposition transcripts, interrogatories, affidavits, and motions to exclude certain kinds of evidence—from scrutiny by the press and public. The entire cache of pretrial documents, more than 6,000 pages of them, are now available online. Andrea Burkhart, a criminal-defense lawyer in Washington state and a Depp supporter, crowdsourced the $3,000 or so that it cost to upload them to the Internet.

I received a lot of press inquiries about the files. Here is the statement that I released to everyone who contacted me except Kat Tenbarge, who gets nothing. #unsealed pic.twitter.com/NzxkwP7qbx

— Andrea Burkhart 🐟🐟🐟🐟🏴☠️ (@aburkhartlaw) August 1, 2022

These documents included tantalizing material unearthed by Depp’s legal team that never made it into the trial, including evidence that Heard had worked as a stripper when she first arrived in Hollywood in 2004, and a 2003 arrest in her native Texas at age 17 for driving with a suspended license that might have resulted from her involvement in a vehicular homicide that caused the death of a friend. Most sensational, though, were nude photographs of Heard in the possession of Depp’s lawyers. Heard had been one of several female celebrities (including Rihanna and Kim Kardashian) whose nude images hackers had downloaded from iCloud accounts in 2014 and uploaded to sites like Reddit and 4Chan. Leaked photos and videos purporting to depict a naked or nearly naked Heard can still be viewed on Internet porn sites to this day.

Depp’s legal team insisted it had no intention of introducing these photos to try to prove their client’s case—but it reserved the right to use them to impeach any claim that Heard had been beaten and bruised by Depp, then her fiancé, during the times they were taken. That didn’t stop media commentators from accusing Depp and his lawyers of trafficking in “revenge porn.” As Guardian columnist Arwa Mahdawi wrote on August 10th, this was “pure nastiness designed to humiliate Heard. It’s also a horrible reminder that if a woman doesn’t lead a perfectly chaste life, the world will find a way to cast her as a ‘slut’ who is responsible for anything that happens to her.”

About a dozen hitherto Depp supporters who had entered “likes” on a June 1st Instagram post by Depp thanking the jury for giving him his “life back” with its verdict, withdrew them, including actress Halle Berry and model Bella Hadid. On November 16th, Gloria Steinem, along with about 130 other activists, scholars, and organizations published an “open letter” excoriating the treatment Heard had been forced to endure as a result of losing the lawsuit:

In our opinion, the Depp v. Heard verdict and continued discourse around it indicate a fundamental misunderstanding of intimate partner and sexual violence and how survivors respond to it. The damaging consequences of the spread of this misinformation are incalculable. We have grave concerns about the rising misuse of defamation suits to threaten and silence survivors.

We condemn the public shaming of Amber Heard and join in support of her. We support the ability of all to report intimate partner and sexual violence free of harassment and intimidation.

VI.

What, then, are we to make of all of this? Much of the testimony heard in London and Virginia was so similar that it seems to leave an unbridgeable chasm between Judge Nicol’s ruling in November 2020 and the jury’s verdict two years later. A similar chasm separates legacy opinion columnists from a large contingent of the general public who followed the legal proceedings online and on cable. Every morning, as he arrived at the Fairfax County courthouse, Depp was greeted by crowds of women shrieking their adoration and trying to pass him gifts. The Depp-Heard trial was likely the most exciting thing that had ever happened to the sedate, largely upper-middle-class Fairfax County, and there is no doubt that Johnny Depp has a huge female fanbase.

But even if we correct for silliness, fangirls gone gaga, and the rhetorical excesses of Depp’s most fanatical supporters, the social-media reaction to Amber Heard indicated a deep skepticism among lay trial watchers—not just of Amber Heard’s claims of repeated beatings and sexual violations but of #MeToo ideology in general. Their doubts were shared by the seven jurors who sat through the entire proceeding and heard both sides of the argument. Meanwhile, the feminists at the Atlantic, the Guardian, and the New York Times all lined up behind the view expressed by the British legal establishment a year and a half before, and they continue to support Heard to this day.

To try to understand what had happened, I spent the summer watching the Depp-Heard trial on YouTube. Poring over the hours of trial testimony did not convince me of the misogyny of the jury or the American legal system. It did, however, lead me to appreciate the strategic brilliance of Depp’s lawyers, who methodically constructed their case like an edifice of architecture.

VII.

The Washington Post was not named as a defendant in Depp’s suit, but Fairfax County Superior Court was selected as the trial venue because the newspaper’s computer servers are located there. Depp was seeking $50 million in damages to compensate for lost earnings occasioned by Heard’s article plus an unspecified amount in punitive damages. Heard did not file her counterclaim, seeking $100 million in damages from Depp, until August 10th, 2020—after arguments in the UK libel trial involving the Sun newspaper had concluded but before Justice Nicol had delivered his judgement. Heard charged Depp not only with defaming her but with organizing an Internet bot campaign to get her removed from the Aquaman 2 cast.

Not only did Depp maintain that he had never struck Heard or committed any physical violence against her, but he alleged that she had punched him, burned his face with at least one cigarette, and thrown objects at him on numerous occasions. During an altercation on March 23rd, 2015, at Depp’s Eastern Columbia penthouse about two weeks after the Australia episode, Depp alleged that Heard had thrown a can of Red Bull at him. (Heard alleged that Depp had been trying to push her sister Whitney down a flight of stairs and that he had thrown the can.)

One of the hurdles Depp’s lawyers had to overcome was Johnny Depp himself. Depp had been extensively cross-examined during the UK trial, so they knew it would be pointless to deny his massive drug and alcohol consumption or the erratic behavior it sometimes produced. Indeed, Heard’s lawyer Ben Rottenborn devoted two full days of cross-examination of Depp in Virginia—on April 21st and 25th, 2022—to exploring the crevices of Depp’s addictions, and his history of taking out his rages on physical objects.

The jury got to see the kitchen video—twice—as well as photos that Heard had taken of Depp apparently passed out or nodding, bottles and drug paraphernalia scattered about him. They saw a photo taken by Heard’s friend Rocky Pennington of a discarded wine bottle in a hallway, allegedly after the May 21st, 2016 debacle, and further stills of the damage Depp had allegedly caused by writing with his own blood and black paint on mirrors, walls, lamps, cushions. He had even defaced some of Heard’s artworks (she painted as a hobby) during the Australian catastrophe, and the jury saw it all. Depp’s team evidently decided it would be shrewdest to simply treat Depp’s substance abuse as a given, and it was.

So, Depp was not the first or even the second plaintiff’s witness, but the ninth, taking the stand on April 19th after members of the medical team in charge of treating his dependencies had already testified. These witnesses all offered somewhat different and often contradictory accounts of events that Heard had described in her UK testimony. Several of them testified to having had unpleasant personal encounters with Heard. Furthermore, one of the fortuitous (or possibly planned) effects of this strategy was to dramatize the amplitude and strangeness of Depp’s apparent immersion in a world saturated with luxury accoutrements, alcohol, and drugs. That world was entirely dominated by Heard but entirely financed by Depp.

The first witness Depp’s lawyers called to the stand, on April 12th, 2022, was Christi Dembrowski, his older sister and his longtime personal manager. One of Dembrowski’s tasks as a witness was to suggest that Depp’s marriage to Heard was a recapitulation of their parents’ tumultuous marriage in rural Kentucky. This had been an unhappy and poverty-plagued arrangement that involved many family moves from town to town. According to Dembrowski, Depp’s mother, Betty Sue, whom Depp both loved and feared, had regularly hit and thrown ashtrays and other heavy objects at their father, John Christopher Depp, and the four children, of whom Johnny was the youngest. “We would run and hide,” she testified.

In 1978, the elder Depp abandoned the family, who were by then living in Florida, and the parents divorced. Johnny Depp was just 15, and he dropped out of high school to try to forge a career as a musician (he had played the guitar since age 12). Betty Sue made another unfortunate marriage, and died at age 81 at Cedars-Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles on May 20th, 2016. This was the day before the final penthouse conflagration that led Heard to file her divorce papers. Dembrowski testified that she had routinely booked an extra hotel room on Depp-Heard trips, to which Depp could flee when he fought with Heard—something she had never done during his 14-year relationship with French singer-actress Vanessa Paradis, the mother of his two children.

The more important purpose of Dembrowski’s testimony, however, was to introduce the jury to Depp’s distinctly odd living arrangements at the Eastern Columbia Building where his marriage blew up. That building, sheathed in turquoise-glazed tiles and topped by a tower boasting enormous clock faces and the word “Eastern” in blazing white neon on all four sides, was—and still is—an Art Deco architectural masterpiece. It had somehow survived the demise of the department store that once occupied its premises, as well as the general decay of the surrounding neighborhood that had been Los Angeles’s premier shopping district during the early 20th century.

A thing I’ve learned covering the Johnny Depp-Amber Heard defamation trial: Depp owns at least 5 penthouses at the Eastern Columbia Building in DTLA. pic.twitter.com/xFFamptrAc

— Vanessa Romo (@vanromo) April 20, 2022

The Eastern Columbia Building was central to the Depp-Heard trial. The two-story penthouse where the couple lived was one of five clustered on the building’s rooftop next to the swimming pool. Depp had bought them all in 2002 and 2007, soon after the conversion to luxury condos. Multiple homeownership was a feature of Depp’s extravagant style in real-estate acquisition. On Sweetzer Avenue in West Hollywood, he owned not just the 1920s castle that was his alternate Los Angeles home but also four of its cul-de-sac neighbors. During his years with Paradis, he lived in what the press described as a “French village” that he still owns near Saint-Tropez (it is actually a private estate with multiple guest houses and a freestanding chapel).

The second witness called by Depp’s lawyers was their client’s longtime friend Isaac Baruch, a former bandmate from the 1980s who had been living courtesy of Depp in one of the penthouses since March 2013 while trying to forge a second career as a painter. This choice of witness was inspired. A chatty New York Jew right out of Central Casting complete with Brooklyn accent, Baruch alternately cast joking asides that made the jury chuckle and teared up as he emotionally recounted his version of the events on the evening of May 21st, 2016. He testified that he had returned home with a friend at about 9.30pm and noticed broken glass in the hallway and “wine all over the walls.” There, he encountered Rocky Pennington’s boyfriend (and later, briefly, husband), Josh Drew, who told him it had been a “rough day.” Baruch and his friend then went to his place where they socialized for a while, the friend left, and Baruch went to bed at about 11pm.

Baruch provided a geographic and demographic guide, including a floor plan (introduced as a plaintiff’s exhibit) to the penthouses and their occupants. He had lived in Penthouse 2, adjacent to Depp and Heard in Penthouse 3. Pennington and Drew occupied Penthouse 1 rent-free, Heard’s sister Whitney lived rent-free in Penthouse 4, and Penthouse 5 served as a workroom for Pennington’s jewelry business and a multiroom closet for Heard’s clothes. Another Heard friend, Elizabeth Marz, who was on the premises on May 21st, also lived briefly in one of the penthouses. (iO Tillett had also lived at Depp’s expense for a time, but in one of Depp’s houses on Sweetzer Avenue.)

In short, four of the five dwellings were under the control of Heard and a predominantly female Heard posse whose members came and went freely, their living arrangements entirely underwritten by Depp, who was sole owner of the premises. Pennington and Drew testified that Pennington even had her own master key to all the penthouses. Although Depp never returned to the Eastern Columbia building after May 21st, Heard continued living in Penthouse 3 until December 2016. Depp sold all five penthouses in 2017 for $10.3 million.

The next day, May 22nd, according to Baruch’s testimony, he encountered Heard in the company of Drew, a man whom she introduced as a security guard she had just hired (Baruch: “He gave me a card, which I lost”), and two locksmiths whom she had summoned to change the locks on Penthouses 1, 3, and 5, because, as she said, Depp had become “violent.” Heard told Baruch that Depp had thrown a phone at the right side of her face, but he testified that he could see no bruises, swelling, or redness. He said he had made a little joke about her beauty on one side outshining the other side and kissed her on her right cheek. She was dressed in jeans and a t-shirt and appeared to be wearing no makeup.

Baruch testified that on May 23rd, 24th, and 25th, he again saw what he believed to be a makeup-free and unbruised Amber Heard. On May 24th, Heard was with her sister Whitney, Mélanie Inglessis, Heard’s makeup artist, and two other women, all of whom “were laughing.” On May 25th, he encountered Heard and Whitney entering the building as he left. He also said that, at the invitation of building security, he had viewed elevator camera footage from the week of May 21st showing Whitney throwing a fake punch at her sister, provoking mirth in both. He didn’t learn that Heard had filed for a restraining order until he saw a photo of her now-marked-up face on the Internet.

The third witness was Brandon Patterson, who provided a videoed deposition. Patterson was general manager of the Eastern Columbia building. His only function in the trial was to verify the locations, authenticity, and time-stamp data of surveillance video from dozens of 24-hour cameras positioned inside the building. Of particular interest was the camera inside the private elevator that ran from the penthouses to the front desk on the ground floor and then down to the underground parking garage. The slow-moving videos, from May 23rd and May 24th, 2016, spoke for themselves. In murky security-camera black and white, the jurors could see Heard ascending and descending with her coterie of female friends as they apparently moved items out of the penthouses. They could glimpse, repeatedly if dimly, her apparently unblemished face and decide for themselves whether or not she had manufactured the black eye and bruises that had appeared so prominently in the photos published by TMZ and People.

Eastern Columbia’s elevator security footage proved to be some of the most powerful evidence that Depp’s team presented. During Heard’s cross-examination on May 17th, 2022, Depp’s lawyer Camille Vasquez showed the jury a clip time-stamped at around 11pm on May 22nd, 2016. It showed Heard, barefoot, tousle-haired, and clad in a nightgown and overcoat as she escorted a backpack-wearing James Franco up the elevator while the two nuzzled each other’s heads. Vasquez’s legal purpose in displaying the video was to counter Heard’s assertion at trial that she had been mentally “falling apart” with “panic” over the prospect that Depp might return to the penthouse. But the effect of the late-night footage was also implicitly lubricious, even though Heard testified that Franco was simply a “friend” who “lived next door” and had come over to console her after “I had exhausted my support network with my usual friends.”

Another elevator video was leaked to the Daily Mail in March 2020, but the leaked footage contained no time stamp and played no part in the trial. It showed Amber Heard, this time barefoot and draped in a beach towel or blanket cuddling in the arms of Elon Musk. Depp maintained that his wife had started an affair with Musk (whom he derisively nicknamed “Mollusk” in texts to his friends) a month into their marriage in 2015. Musk, however, has insisted that he met Heard for the first time at another Met Gala, in early May 2016, which she had attended alone because she and Depp were by then already thoroughly estranged. Musk and Heard were an off-and-on item in 2016 and 2017 and again, briefly, in 2018. Both Musk and Franco were on Heard’s witness list for the Virginia trial, but neither ended up testifying.

VIII.

All of this offered the jury—and the hundreds of thousands of people following the proceedings online and on television (both Court TV and Law&Crime reported record-breaking viewer numbers)—a glimpse into the intimate lives of celebrities; lives so different from those of even reasonably wealthy people that they can seem bizarre and grotesque. Neither Depp, who maintained shifts of bodyguards and drivers outside his penthouses and elsewhere, nor Heard ever seemed to be alone. Paid and unpaid entourages moved with the couple like schools of fish wherever they went.

Among the well-compensated hangers-on were Dr. David A. Kipper, MD, a self-described addiction specialist in Beverly Hills now in his 70s with a shock of white hair, and his contract nurse at the time, Debbie Lloyd, a lanky, slow-talking middle-aged blonde who looked like a burned-out surfer. Both testified by videoed deposition. Kipper offers 24/7 “concierge” detox treatments to wealthy addicts at their homes. These can involve, as was the case with Depp, prescribing alternative drugs that are supposed to help users cope with withdrawal.

From 1998 to 2007, Kipper had been under investigation by the Medical Board of California for allegedly overprescribing detox drugs that were themselves addictive, as well as alleged unprofessional conduct and gross negligence. One of the complainants was Ozzy Osbourne, who had staggered glassy-eyed around his Beverly Hills mansion in his reality show during the early 2000s—possibly because, as a Los Angeles Times examination of his prescriptions revealed, he had been on a Kipper-prescribed regimen of 13 different medications, including opiates, tranquilizers, amphetamines, antidepressants, and an antipsychotic. In the end, the board merely found that Kipper had failed to maintain adequate records and issued a public reprimand that required him to take classes in record-keeping and medical ethics.

Depp hired Kipper in May 2014, shortly after the alleged airplane kicking incident, to help him detox from what Kipper described in his deposition as “polysubstance abuse”: a “combination of alcohol, opiates, benzodiazepines, and stimulants, cocaine.” The opiate in question was Roxycodone, an Oxycontin clone, the benzo was Xanax, and the stimulant was Adderall. Kipper prescribed Depp a thrice-a-day cocktail of muscle relaxants, lithium, tranquilizers, and anti-hypertension medications. Kipper testified that he had hoped to wean Depp from Xanax as well as opioids, but Depp couldn’t handle the requisite detox drugs, so he more or less remained addicted to benzos throughout his multiyear treatments by Kipper. Depp also remained on Adderall for years, but Kipper testified that he hadn’t actually been addicted to that particular amphetamine.

The Kipper-prescribed drugs were part of a disastrous 10-day detox session presided over by Kipper and Lloyd in August 2014 on Depp’s Bahamas island, during which Heard, along on the trip to help with the medications, alleged that Depp slapped her and kicked her to the ground during withdrawal spasms from the Roxycodone. (Depp denied this, maintaining that he had been too weak from withdrawal symptoms and that Heard had been deliberately withholding Kipper’s prescribed drugs.)

Kipper and Lloyd were also in residence, in nearby hotels, during the finger-severing episode in March 2015 at Depp’s Australian digs. Kipper had driven to the house after receiving a semi-incoherent text from Depp on March 7th, 2015:

FAR MORE HURTFUL than her venomous and degrading endless ‘educatinal [sic] ranting...???’ is her hideously and purposefully hurtful tirades and her goddamn shocking treatment of the man she was meant to love above all.

Kipper found Depp sitting inert and bleeding in his car. He raced into the now-thoroughly wrecked house to rummage through wastebaskets while Lloyd hunted for the missing finger. It was ultimately found by Depp’s major-domo, Ben King, wrapped in a bloody paper towel on the floor near the bar where Depp testified that Heard had thrown a vodka bottle at his hand. King packed the digit in ice, and it was ultimately surgically reattached. One of King’s next jobs, after escorting a “hysterical” Heard back to Los Angeles, was to clean up the Australian premises. A reconciled Depp and Heard moved right back into the repristinated dwelling in April 2015 for more Pirates 5 filming.

Embarrassingly for a physician who had been reprimanded in the past for inadequate record-keeping, Kipper testified in his deposition that he could not produce any records, either paper or electronic, for the routine drug tests Depp had apparently undergone in his office during the latter part of 2014 and the whole of 2015. Kipper testified that “a flood in our office in 2014, October” might have obliterated some of the pertinent notes. But he testified that his office records from 2016 onwards showed that Depp never did get off—at least during his relationship with Heard and afterwards—most of the drugs for which Kipper was treating him. Nevertheless, according to trial testimony from Depp’s former business manager Joel Mandel, Depp kept Kipper on a retainer that yielded fees as high as $100,000 a month. Kipper’s extant office records indicated that while Depp may have weaned himself off opioids, he continued to test positive for cocaine from 2016 through 2019, as well as THC (Depp never counted the marijuana he regularly smoked as a drug, and during his 2018 Rolling Stone interview at a house he owned in London, the table was reported to be piled with hashish and tobacco). He also continued to test positive for benzos and Adderall, Kipper’s notes showed.

Kipper also testified that right after the finger-severing incident of March 2015, he had informed Depp that he was “withdrawing” his “care” of him because of Depp’s failure to comply with his treatment regimen, including abstention from the drugs from which he was supposed to be detoxing. He testified that about a week later Depp came through with a promise to remain sober, at least through the surgery required to reattach the finger.

Depp’s onetime bandmate and since-estranged friend, music producer Bruce Witkin (whose sister-in-law had been briefly married to Depp during the 1980s), appeared by deposition as a witness for Heard, pronouncing Kipper’s treatment program for Depp to be a “scam.” Indeed, one of the odd features of the Kipper arrangement was that he also provided Heard with a contract nurse, Erin Boerum Falati, who supplied Heard with Kipper-prescribed medications. These, Falati testified in her videoed deposition, were intended to treat Heard’s reported anxiety, bipolar symptoms, eating disorders, codependency issues, and insomnia. Both Falati and Lloyd were regular fixtures at the Eastern Columbia penthouse complex.

In other words, Johnny Depp, for reasons at least in part of his own making, inhabited a world more or less controlled by people whose existence in his life he helped underwrite but whose interests did not necessarily coincide with his own. He seemed to have few real friends: Baruch; Bettany, who seemed more like a partner in drug overconsumption; and Marilyn Manson, another alleged drug buddy who currently has his own #MeToo problems—a defamation suit is pending against a former girlfriend, actress Evan Rachel Wood, who has accused him of “grooming” her over the years for “sexual abuse.”

Heard, on the other hand, had woven her own friends thoroughly into the couple’s life. In 2010, she came out as bisexual, reporting relationships over the years with women as well as men. How her complex sexual nature precisely affected the dynamics of her relationship with Depp, sexual and otherwise, is impossible for an outsider to gauge, but the company of women seemed to be as important to her as—or perhaps more important than—the company of any male lover or husband. Online photos of her wedding ceremony in February 2015, taken by airborne paparazzi hovering above the beach at Depp’s Bahamas island, are telling: a thicket of bridesmaids standing behind her plus Josh Drew and iO Tillett Wright, Heard’s best man. Depp, by contrast, has only a single attendant, his then-11-year-old son, Jack, as his own best man (his then-15-year-old daughter, Lily-Rose, was conspicuously absent from the celebration).

The Virginia jurors never saw those photos, which were not trial exhibits. But they did see the Eastern Columbia elevator video of Heard and her female companions and heard Baruch’s testimony about the laughter. They heard from her former assistant, Kate James, who testified that right after the May 2014 airplane incident in which Depp had allegedly kicked, publicly humiliated, and traumatized Heard, James’s first task was to pick up a swimsuit at Heard’s apartment and deliver it to the celebrity hotel Chateau Marmont on Sunset Strip, where Heard had checked in on Depp’s tab as soon as she got off the plane. James testified on video:

And so, I was nearly placating her, I would say, and especially when I saw she was there with about four or five girlfriends and basically having fun, enjoying each other down by the pool. That’s why she needed a swimsuit. And then they proceeded to hang out all day drinking while I sat around waiting with my son. Actually, I think it was a Sunday that day, I remember. We had to wait all day while they just hung around drinking by the pool.

James and Heard engaged in a kind of courtroom catfight as the proceedings unfolded, with James accusing Heard of screaming and spitting at her, chiseling down her salary, having a “kick the dog” relationship with Whitney, and using a range of drugs that included psychedelic mushrooms, ecstasy (MDMA), and cocaine, plus plenty of wine. Heard, in turn, accused James of drinking on the job and leaving her small son unattended in her car.

Significantly, like almost all of Depp’s witnesses, James testified that she never saw Depp lay a hand on Heard or any bruises, bleeding, or abrasions on Heard herself. Six different bodyguards and others who had worked for Depp in Los Angeles and the Bahamas also testified to that effect. One of them, bodyguard Travis McGivern (who made the jury laugh by vaping through his videoed testimony), said he had witnessed Heard spitting on and, on one occasion, throwing a Red Bull can at Depp. All those men had been on Depp’s payroll and so their testimony should be treated with caution. But Alejandro Romero, who worked the front desk at the Eastern Columbia Building, wasn’t. He testified that he had encountered Heard in the building twice on May 25th, 2016, including a trip up the elevator with her and Rocky Pennington. A brief exchange with Leo J. Presiado, one of Depp’s lawyers, unfolded like this:

Presiado: And during that entire period of time taking them up to the

penthouse, walking through the penthouse, and then finally, you leaving

and going back to your desk, you did not, you looked at Ms. Heard

during that time period, correct?

Romero: That’s correct.

Presiado: And you looked her in the face, squarely in the face,

correct?

Romero: Correct.

Presiado: And you didn’t notice any swelling, correct?

Romero: Correct.

Presiado: Did you see any swelling?

Romero: No.

Presiado: Did you see any bruises?

Romero: No.

Presiado: Did you see any marks on her of any kind?

Romero: No marks at all.

This was not helpful testimony for Heard. After Depp himself had been on the stand for four days, three Los Angeles police officers took the stand in turn. They had visited the penthouses twice between 9pm and 11pm on May 21st, 2016, to investigate the report of domestic violence, in response to Tillett Wright’s relayed 911 call from New York. They found the premises tidy (except for the stains and wine bottle in the hallway shown to them by Drew) and a weeping and red-faced Amber Heard. Not only did she not display any bruises or contusions, according to the officers’ testimony, but she refused to cooperate, even after a female officer, Melissa Saenz, took her aside to talk privately. Bodycam video evidence from one of the officers showed Pistol and Boo scampering over sofas and end-tables and a male voice asking, “Who’s Amber?” while a blonde female figure who may or may not be Heard lurks in the background.

All that remained was for Shannon Curry, a forensic psychologist who had administered a court-ordered examination of Heard, to testify that Heard suffered from a combination of “borderline personality disorder” and “histrionic personality disorder.” Curry described sufferers from the former as highly sensitive to rejection, short on self-control, and “marked by anger, cruelty toward people less powerful, concerned with image, attention-seeking, and prone to externalizing blame, a lot of suppressed anger” that may explode outwards into “assaultive” behavior. Love-objects of borderline personalities typically go from “idolized to dumpster,” often with violent consequences, Curry said.

IX.

Against this strategic juggernaut, Heard’s lawyers clearly faced difficulties mounting a defense for their client. For a start, it seemed that the only witnesses able to testify that they had personally seen signs of physical abuse to Heard were her already familiar-to-the-jury set of friends: her sister Whitney, Rocky Pennington, Josh Drew, iO Tillett Wright, Elizabeth Marz, makeup artist Mélanie Inglessis, and her acting coach Kristina Sexton, who had been with her, along with Whitney and Pennington, at the trailer complex where Heard said Depp had performed the cavity search in 2013 and inflicted massive damage on the interior of the trailer.

All testified to having seen cuts and bruises on Heard at various times, and to having seen or heard violent arguments between her and Depp, often accompanied by Depp’s signature property destruction. Pennington had taken photos of Heard’s bruised face, a bare spot on Heard’s head after the December 15th, 2015, argument during which Heard said Depp had pulled out a clump of her hair, and also the blonde clump itself, still lying on the floor when Pennington took the photos the following day. Pennington also kept an extensive photographic record of alleged Depp-caused damage to the penthouse complex on the evening of May 21st, 2016, including the destruction of some of Pennington’s jewelry-making materials. Marz testified that Depp had terrified her that evening by rushing past her screaming, “Get the bitch out!” Inglessis had done Heard’s makeup for a television appearance on December 16th, 2015, and remembered covering some discoloration under Heard’s eyes that “could have looked like somebody had head-butted her lightly.”

The only problem was that none of these friends had ever personally witnessed Depp inflicting blows on Heard. Even Pennington, who testified that she had rushed into Penthouse 3 using her master key on the night of May 21st, 2016, after receiving an alarmed text from Heard, saw only Heard sitting on a couch by the time she arrived while Depp stood 10 feet away from her along with two of his bodyguards. The closest Heard’s legal team came to an eyewitness account of Depp’s alleged violence toward women was a videoed deposition by actress Ellen Barkin, who testified that Depp had thrown a wine bottle in her direction during an altercation with friends when the two were having a brief affair in 1994.

It didn’t help that Pennington testified that her friendship with Heard had collapsed in 2018 after the two tried sharing a house; Heard had hit Pennington during an argument not long after they moved in. Nor that Inglessis had quit working for Heard as her makeup artist because there was always “some conflict, some fight, some physical fights, some verbal fights, some kind of problems.” Nor that Whitney and Depp, according to the former’s testimony, continued their friendship even after the alleged staircase incident on March 23rd, 2015. On October 2nd, 2015, Whitney texted Depp: “I love both of you so much and would fucking stay out of it if I thought this shit were past the point of no return, but that’s not where you guys are at.” (At trial, she insisted that she had written this only because Amber wanted to stay with Depp.)

Furthermore, as the records unsealed by Azcarate in July indicate, Heard’s lawyers were unable to obtain a court order for their own psychologist to examine Depp just as Depp’s psychologist had examined Heard. This was deeply disappointing for the defense, but there was a reason for the apparent inconsistency: Heard had alleged emotional harm as part of her countersuit, which made her mental condition central to her case. Depp, on the other hand, had alleged only economic damage: lost roles and earnings, so his mental condition was legally irrelevant. Heard’s team did their best to make up for this setback. Heard’s own forensic psychologist, Dawn Hughes, testified that Heard suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder as a victim of domestic violence. This allowed Hughes to develop a hypothetical abuser profile while on the witness stand that neatly matched Heard’s own description of Depp: “[t]he coercive control, the surveillance, the obsessive jealousy, the possessiveness, the psychological abuse,” all of which could be exacerbated by alcohol consumption, Hughes said.

Heard’s lawyers also called to the stand the very doctor whom they had originally hoped would be able to conduct a court-ordered exam, psychiatrist David Spiegel. Spiegel, who had never met Depp, nonetheless offered a diagnosis of his mental state—narcissistic personality disorder and drug-induced cognitive decline—based solely on Spiegel’s examination of the other court records and testimony in the Depp/Heard litigation. This was a clever move on the part of the defense, although it is difficult to gauge how successful it was with the jury. One of Depp’s lawyers, Wayne Dennison, grilled Spiegel extensively on cross about the latter’s likely violation of the American Psychiatric Association’s “Goldwater rule,” which holds that it is unethical for psychiatrists to make armchair diagnoses of people they have not examined personally.

X.

But just as the Depp team’s greatest obstacle to winning its case was Johnny Depp, the Heard team’s greatest obstacle to winning its case was Amber Heard. Everything about her presence in the courtroom went wrong, starting with her personal appearance. During her 20s, Heard had been strikingly beautiful, with leonine cheekbones and thick blonde hair that she usually wore in waves tumbling down her back. For social and publicity occasions, she chose fashionable clinging dresses and gowns.

But for the Virginia trial, Heard styled her hair close to her head in tight braids and chignons, or in snakelike curls that made her face look puffy and bloated. She dressed in severe high necklines and unflattering menswear jackets in somber colors that made her look like a warden in a 1970s Nazisploitation movie. Watching her on YouTube, I wondered whose idea this was. If you are being accused of throwing punches at your husband and slapping your best friend around, this is surely not a good look. Worse still, as the trial wore on, Heard’s solemn monotone became grating.

Time hasn’t been much kinder to Depp. Saddled with weight gain, forehead creases, and a dramatically receding hairline, he looked like his own picture of Dorian Gray. It was hard to remember the heartthrob who had squired Kate Moss during the 1990s. Still, while his looks may have faded, his charisma has not yet deserted him, and in his pinstripe Mafia suits and his tattooed fingers loaded with rings, he came off as a jaunty Jack Sparrow Goes to Court. The contrast with his lugubrious-looking former wife produced a charm gap that the defense never succeeded in closing.

There was, however, something genuinely affecting about Heard’s testimony on direct—at least up to a point. She told a tale of pluck and grit: the working-class girl from a tiny Texas town who grows up helping her father train horses and hoists herself into Hollywood by her own bootstraps. There was this testimony, on May 4th, 2022:

I was a scholarship kid at a Catholic school growing up, several different Catholic schools. … [A]s long as I maintained an A average, I enjoyed the benefit of a scholarship. And I did that until I realized that I could take my GED and SATs early, and I did that and placed out of school and effectively left school 16 years old. […]

I took any job that I could. I worked at my father’s construction company, sometimes, you know, just administrative stuff … I answered phones. And I worked at, like, a modeling agency that was also, you know, offered photography classes, makeup classes, hair and makeup classes, for people that were pursuing a career in entertainment. And I started taking classes that I paid for by working there. … And I eventually worked there long enough to be able to pay for my headshots, which are the pictures that you use in the industry to promote yourself, you know, in whatever, acting, modeling, or both. […]

I did a small job in Texas where I played a part in a movie. And the actor in the movie that I was playing opposite had an agent visiting him from LA. And I met her on set and she said that she had heard about me from another bit part I did. … And she said, “I have heard about you in this town and I’d love to meet you in LA if you’re ever out in LA” And I was like, “When can I come?” And she made an appointment with me for the following week and I used all but $180 or something to get out there. … I didn’t know anyone. I was 17.

I went to every audition, every casting, every meeting, every appointment that I could. I put myself out there. I didn’t have a car because those are expensive. So, I took the bus around LA. It was before smartphones, I had a Thomas guide in my bag and a change of tank tops. I went to about ten auditions sometimes a day and would change clothes if I needed to in the back of, you know, the bus I was taking. And I got a bit part on one thing, and then I got a bit part on another thing, and then eventually my roles kind of became more important or bigger.

I’m a sucker for this kind of story, especially since in Heard’s case I hadn’t yet learned about her exotic-dancing gigs or her police problems in Texas stemming from her suspended driver’s license.

Heard met Depp in 2008, according to her testimony, when she was 22 and he was 46. He offered her a lead role in The Rum Diary, in which he was starring and also co-producing. It was a passion project for Depp, based on a 1961 novel by one of his idols, Hunter S. Thompson. Released in 2011, The Rum Diary was a critical and audience flop, but during a publicity tour that fall, the two began a secret affair. The relationship was initially kept under wraps because Depp was technically still with Paradis and Heard was technically still with Los Angeles photographer/painter Tasya van Ree, whom she called “my wife.”

During the UK trial, Heard alleged that Depp’s abuse of her did not begin until 2013, after a yearlong honeymoon once the two moved their relationship into the open. But in the Virginia case, she said that Depp had been abusive since 2012—testimony, she claimed, produced by a refreshed memory. (This revised timeline meant Heard had to explain why she had bought her violently abusive boyfriend a large hunting knife for his birthday in 2012, inscribed with the words “Until Death” in Spanish.) And she alleged many more incidences of Depp’s abuse than she had divulged at the High Court in London. Her testimony on May 4th about Depp’s alleged first act of violence sounded persuasive:

I was sitting on the couch and we were talking, we were having a like, a normal conversation. You know, just there was no fighting, no argument, nothing. And he was drinking. And I didn’t realize at the time, but I think he was using cocaine because it was … like, there was a jar, a jar, of cocaine on the table. …

And I ask him about the tattoo he has on his arm. And I said, “What does it say?” And he said, “It says ‘wino.’” And I didn't see that. I thought he was joking. Because it didn’t look like it said that at all. And I laughed. It was that simple. … And he slapped me across the face. And I laughed. I laughed because I didn’t know what else to do. I thought, “This must be a joke.” … I just stared at him, kind of laughing still, thinking that he was going to start laughing, too, to tell me it was a joke, but he didn’t. He said, “You think it’s so funny. You think it’s funny, bitch. You think you’re a funny bitch.” And he slapped me again. Like, it was clear it wasn’t a joke anymore.

Then there was this, from Heard’s testimony on May 5th, 2022, about the bloody Australian weekend in March 2015:

I remember my feet slipping on the tile as he was slamming me from the wall to the countertops. At one point, he has me up against the wall and he’s punching the wall. He had my, you know, nightgown and kind of ripped it off my chest. I remember at one point he’s teasing me. He’s taunting me that he has my breasts in his hands. My nightgown came completely off. It was ripped off of me. So I was naked and I’m slipping around on this tile and trying to get my footing. … At some point, I’m up against the wall and he’s screaming at me that he fucking hates me, that I ruined his life, ruined his life, over and over.

And he starts punching the wall next to my head, holding me by the neck. I get free from him. I kind of step back from him. And it’s like his energy shifted to the phone. There was a wall-mounted phone on the wall next to where my head was. And he went from punching the wall to, like, realizing there was a phone there, and he picked up the phone and he’s screaming. … He picks up the phone and starts bashing the phone against the wall, against the wall where I was just being held. And I remember kind of having some distance on what was happening and watching him do this, and it was like his energy had shifted. And I was that phone all of sudden. And he’s just over and over again smashing this phone into the wall over and over again screaming at me, and I was watching the phone. Every single time he pulled his hand back, it was just breaking into pieces, that I remember thinking this phone is disappearing. He’s smashing it to smithereens just going into the wall. …

And, at some point, he’s on top of me, no phone, but screaming the same thing, “I fucking hate you. You ruined my fucking life.” I’m on the countertop. He had me by the neck, and it felt like he was on top of me, and I’m looking at his eyes, and I don’t see him anymore. I don’t see him anymore. It wasn’t him. It was black. …