Environmentalism

It’s Time the Green Movement Stopped Demonizing Nuclear

The pro-nuclear movement is gaining traction despite vocal opposition

During the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt (also known as COP27), ELLE UK Contributing Editor Aja Barber couldn’t contain her exasperation at news that pro-nuclear-power demonstrators were in attendance.

“They do this every COP,” she tweeted. “It’s mortifying every time! Nuclear power remains an environment[al] justice issue for me because only the poor end up with the plant and the waste within spitting distance of their neighbourhoods.”

Barber also claimed (falsely) that people living near nuclear power plants were suffering from “real unexplained cancers,” and that those who doubted this fact were racist whites who doubted the perspective of “brown and Black people.” (Barber ignored the fact that I’m brown myself.)

As the founder of Emergency Reactor, a UK-based group of pro-nuclear activists concerned about climate change, I felt the need to call Barber out for spreading misinformation. The people I’ve met who live near nuclear power stations are generally happy to have the jobs and other benefits that these facilities bring. Nuclear energy generation doesn’t emit greenhouse gases or any of the smog we commonly associate with fossil-fuel-based power plants. Modern construction and operating methods ensure that nuclear-power facilities are quiet and safe.

Yet to Barber, anyone who makes the case for nuclear power—including me—must be a “lobbyist.” Nicolas Haeringer of the anti-fossil-fuel group 350.org similarly accuses COP activists of being part of “an industrial lobby pretending to be a movement.” It’s as if these anti-nuclear environmentalists will only take others’ concern for the planet at face value if they’ve superglued themselves to a museum, blocked traffic, or spray-painted someone’s business.

(On a separate note, I find it odd to mock activists as “cringe” simply because they express themselves with dance. For years, environmentalists have taken part in all manner of stunts to bring attention to their cause. I took part in multiple dance events when I was a member of the global environmentalist group Extinction Rebellion, including disco in the streets. To my knowledge, no one ever called us “cringe,” or accused us of being lobbyists.)

As it happens, nuclear energy is indeed related to environmental-justice concerns, though not in the way that Barber claims. Rather, it is people who live near coal-fired power plants who, as a 2018 Duke University School of Medicine summary noted, tend to be exposed to pollutants associated with “premature deaths, cardiovascular diseases, lung cancer, low birth weights, higher risk of developmental and behavioral disorders in infants and children, and higher infant mortality.”

Those who are wealthy can, of course, move away from such coal plants. But those who are poor (a condition that correlates with being a member of a racial minority group in many parts of the world) typically must stay put and endure the risk. And so, aside from helping to curb climate change, replacing coal-fired generators with nuclear power stations would also address the environmental injustices that Barber and others speak of.

The kind of misinformation that Barber is peddling is common, unfortunately. For many members of my generation, the dominant image that comes to mind in regard to nuclear power is that of Homer Simpson and the (fictional) radiation-leaking Springfield Nuclear Power Plant. Similarly, our understanding of the industry’s owners and lobbyists was shaped by Homer’s boss on The Simpsons, the selfish and dishonest Montgomery Burns. In my earlier activism, I took it for granted that nuclear power needed to be shut down, along with fossil fuels, in favour of only renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, and hydroelectric energy.

Yet what I eventually found was that the supposedly shadowy nuclear-power lobby didn’t really exist—at least, not on the scale of Big Oil. If anything, in fact, policy-makers and regulators have been overly influenced by anti-nuclear activists, with little countervailing pressure being applied by industry supporters. This is a problem because, as I’ve written previously, “according to multiple scientific bodies, nuclear energy is clean, reliable, and is needed to transition away from fossil fuels in order to combat climate change. No country in the world has been able to decarbonise its electricity sector without … nuclear energy” (except in those cases where substantial hydro energy is an available component of the local energy mix). Even the basic typology used in environmental analysis serves to exclude nuclear options, since, as noted above, nuclear typically isn’t classified as a “renewable” source (as opposed to biofuels, which are classed as renewable but also generate enormous levels of pollution).

Even when I’ve approached nuclear industry representatives on my own initiative, I’ve found they’re curiously reluctant to promote their product. I’ve been advised not to organize pro-nuclear rallies, and even basic quotes for articles have proven hard to obtain. Myrto Tripathi, the founder of the France-based group Voices for Nuclear, has written about the absence of lobbying from the nuclear industry, arguing that while both “fossil and renewable companies have … invested strongly to [assert] influence,” the nuclear power industry has “self‐censored, depriving itself of a major lever for its own development.”

Yet this reticence might be based on an outdated understanding of public sentiment: In the UK, at least, the latest survey data suggests that people are now ready for a discussion about how nuclear energy can be part of our future. Forty-four percent of respondents now agree with the proposition that the government should be encouraging nuclear power generation, compared to 30 percent who take the opposite view. Just a few years ago, those numbers had been reversed.

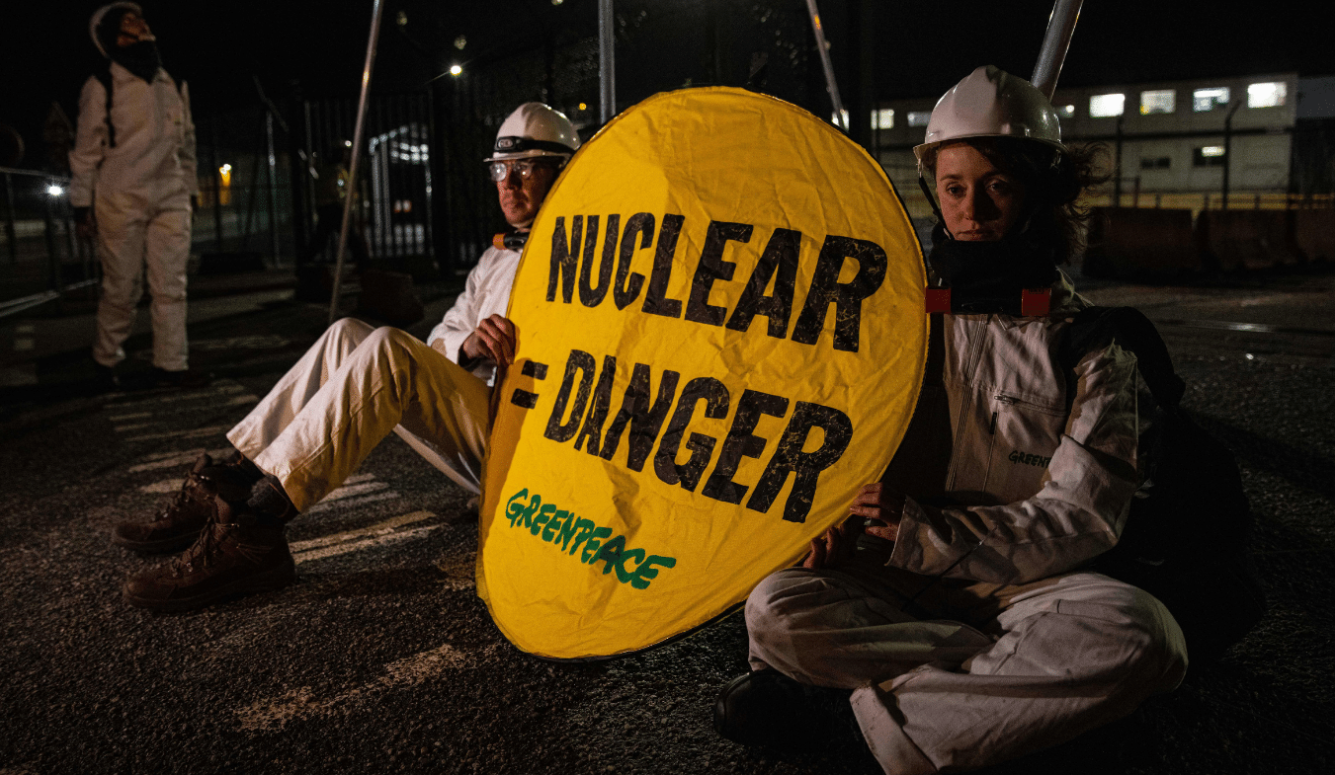

One problem is that, as I noted in a previous Quillette article about this issue, most of the major green groups, including Greenpeace, Green parties, Friends of the Earth, and the Sierra Club, long ago enshrined opposition to nuclear power as one of their core dogmas. They also have done their best to exacerbate fears about rare nuclear disasters, while ignoring the benefits that an increased use of nuclear power could bring—including high-quality, well-paid jobs that often come with great benefits, job security, and union support. These are the sort of things that the progressive Left once fought for.

In some cases, the attacks on nuclear supporters can blur into outright bullying—as illustrated by Finnish biologist Iida Ruishalme’s account of what happened to her and Eric Meyer, founder of the American campaign group Generation Atomic, at COP23 in 2017:

[An] old man started pushing Eric and was really angry, spitting and yelling. [The old man] screamed in his face that he was a fascist … None of the other activists thought this seemed like an objectionable way to behave, and they were happy to let Eric get pushed some 30 meters down the street. When I joined the two of them, the old man started screaming … that I too was a fascist.

In 2021, similarly, at the Fridays for the Future march in Germany, a man aggressively wrestled a placard from a pro-nuclear environmentalist named Britta Augustin and tore it up. In a subsequent statement, Augustin recounts that another fellow protester had compared her to a Nazi—even as Augustin vainly tried to point out that no less an authority than the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change had concluded that nuclear energy is needed to decarbonise our economies. (I am happy to report that Augustin has not been discouraged by such experiences, and helped organize a pro-nuclear rally in Berlin several weeks ago.)

One sign of hope is that young people who work in the industry are beginning to find their voice on a grassroots level. These include members of the Young Generation Network (NIYGN)—an offshoot of Britain’s Nuclear Institute, which describes itself as the only professional membership body dedicated to the nuclear sector. As you might expect, these people look and sound nothing like Homer Simpson: they are organised, intelligent, and networked with counterparts in dozens of other countries.

At the climate march in Glasgow during COP26, I walked alongside NIYGN members, some of whom were appearing at a public environmentalist demonstration for the first time. They told me that they’d never felt welcome at previous events; and, sure enough, many activists at COP26 tried to make them feel unwelcome at this event as well. In my view, these nuclear workers should be considered climate heroes: If anyone is going to help us get out of the current climate crisis, it’s them.

Best of luck to everyone attending #COP27 - especially those supporting @Nuclear4Climate (including a number of YGN members) ⚛️💚🌍

— Nuclear Institute Young Generation Network (YGN) (@NI_YGN) November 4, 2022

We had a fantastic time last year at #COP26 pushing the message that #NetZeroNeedsNuclear - read about our campaign here: https://t.co/x5bAy5mV4j pic.twitter.com/FtN2hiqYVP

The NIYGN volunteers were impressively organised and active at COP26, even going so far as to arrange a flashmob dance ensemble in the centre of Glasgow. They also showcased Bella the giant inflatable gummy bear, who was an instant draw for selfies. Why a gummy bear? Because one enriched uranium oxide pellet, which is about the size of a gummy bear, creates as much energy as a ton of coal, 49 gallons of oil, or 17,000 cubic feet of natural gas. It’s a fantastic visualisation and conversation starter.

A central battleground for this debate will be Germany, whose 12-year-old Energiewende (“energy turnaround”) is supposed to eliminate all non-renewable energy sources—including nuclear—by 2038. But Energiewende has failed, and not just because Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has disrupted energy markets. The scheduled closure of Germany’s last three operating nuclear plants has been put off till April 2023. And an article published in the Journal of the European Economic Association concluded that the drawing down of Germany’s nuclear capacity has had dire economic and human consequences. According to the authors,

We find that the lost nuclear electricity production due to the phase-out was replaced primarily by coal-fired production and net electricity imports. The social cost of this shift from nuclear to coal is approximately 12 billion dollars per year. Over 70% of this cost comes from the increased mortality risk associated with exposure to the local air pollution emitted when burning fossil fuels. Even the largest estimates of the reduction in the costs associated with nuclear accident risk and waste disposal due to the phase-out are far smaller than 12 billion dollars.

Similarly, a 2019 analysis of post-Fukushima energy policy in Germany and Japan between 2011 and 2017 found that these two countries could have prevented 28,000 air pollution-induced deaths and 2,400 metric tons of carbon dioxide (MtCO2) emissions if they’d retained their existing nuclear-power generation capacity instead of making up the difference with fossil fuels. Moreover, the authors found that even by 2019, Germany was still in position to prevent 16,000 deaths and 1,100 MtCO2 emissions by 2035, by reducing coal instead of eliminating nuclear. They also warned that “if the United States and the rest of Europe follow Germany's example [of phasing out nuclear], they could lose the chance to prevent over 200,000 deaths and 14,000 MtCO2 emissions by 2035.”

But the fight to decarbonise our economy can’t be won if legacy environmental groups demonize activists who base their activism on this kind of hard-headed scientific analysis. And so at COP26 in Glasgow, I staged a mock symbolic wedding between renewables and nuclear energy as a means to highlight the common nature of our cause. But as the wedding march played and a crowd gathered to take photos, we were accosted by a group of anti-nuclear activists. They wore balaclavas and masks, held banners reading, “Greenwash zone,” and shouted that we were “shills” for nuclear power. Their tactics were so aggressive that they attracted the attention of police. Several people in our group attempted to talk to them, but all they wanted to do was shout slogans, so we walked away.

Among some environmental puritans, it seems, the insistence that nuclear energy is evil has become an article of religious faith—one that does not even permit them to be in the company of those with pro-nuclear postures. One nuclear worker I met, who shall remain nameless, told me that her date stormed out of a restaurant when she told him she had a job at a nuclear plant. She now feels hesitant about telling people about her line of work.

My own view is that pro-nuclear advocates can’t be shy about inserting themselves into the environmental movement and making their voices heard. And so, at the 100,000-activist march in Glasgow, when my fellow Emergency Reactor activists and I spotted a gap (between Extinction Rebellion and The Green Party, two groups that I used to be a member of, ironically), we jumped in, chanting, “More nuclear, less coal.” Within minutes, the insults started flying: You’re not welcome here. Nuclear waste is destroying the planet. How do you sleep at night doing what you do? After the event, a Scottish Green Party member of parliament named Ross Greer tweeted about how displeased he was to be situated so close to us, and conspiratorially noted that, “every time we slowed down to create some distance, they would slow down too.”

This very odd group waited for the @globalgreens bloc on the #COP26 march then jumped in to march right in front of us. Every time we slowed down to create some distance they would slow down too

— Ross Greer (@Ross_Greer) November 22, 2021

Then at bang on 3pm they left. Almost as if they weren't paid to be there any longer https://t.co/ssdoW9te6L

He also wrote that “at bang on 3pm, they left. Almost as if they weren’t paid to be there any longer”—a comment meant to suggest that we’re on some nefarious actor’s payroll. Given that environmentalists such as Greer pay so much lip service to social justice, diversity, and inclusion, it’s shocking to see the childish and dismissive way in which they prosecute parochial feuds against other environmentalists.

In some cases, in fact, events such as COP26 can feel like dealing with the mean girls from high school. This was the case at one recent Extinction Rebellion event, where a few members of NIYGN showed up in their blue “Net Zero Needs Nuclear” jackets. When they joined hands in a singing circle with others, word got around about who they were, and the other activists reeled in disgust, dropping the hands of NIYGN members lest they be contaminated with pro-nuclear cooties. I don’t think I’ve ever heard of such an obvious effort to bully someone.

As it happens, most members of these NIYGN teams are volunteer activists. But even if they were paid for their efforts—in the same way that staff of the Sierra Club and other NGOs draw a salary—so what? Notwithstanding the smears that have been hurled my way, advocating for nuclear power isn’t any less legitimate than advocating for, say, wind or solar power, even if those industries get better press.

Consider, for instance, Arun Khuttan, a 29-year-old British-Punjabi nuclear worker who works as a sustainability advisor at the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority, the British public body tasked with eliminating nuclear-related site hazards and developing waste solutions. Yes, he’s professionally connected to the nuclear industry (and has been denigrated by some, including even some close friends, as a result). But he comes by his enthusiasm for nuclear power honestly, having earned an MSc in Advanced Nuclear Engineering at Imperial College London.

“I was originally very enthused by fusion reactors,” he told me. “[But] within a few weeks at Imperial, I realised that fission already does what we think we want fusion to do. Since then, I have dedicated my life to nuclear fission. [It’s] one of the biggest gifts of our time.”

And far from being a “shill,” Khuttan has a healthy understanding of the duties and safeguards that have to be respected if nuclear power is going to remain safe and viable:

[In the UK], it is tangled up in a complex history, and there are current legacy wastes which are problematic. Whilst these shouldn’t stop development of new nuclear [power sources], cleaning up the legacy responsibly is one of the best things we can do for nuclear. By ‘closing the [production] loop,’ and showing that it can be done, we automatically make the case for new nuclear, which already puts in place significantly more planning [for] decommissioning than the legacy sites we are [now] responsible for cleaning up.

Another fellow member of NIYGN is Hannah Fenwick, a senior commercial officer at National Nuclear Laboratory. She’s 28 years old, with a BSc in Chemistry. Fenwick picked the nuclear sector precisely because it’s “where I could have a big impact to support decarbonisation and access to clean energy.”

“Family and friends have made jokes about the perceived risks [that go with] working in nuclear,” she adds. “[They] assume I do a ‘dirty’ job, likening it to working on weapons, defence, or oil and gas.”

The fact is that some aspects of any energy sector will be “dirty” in some way. One argument often directed against nuclear power, for instance, is that it depends on mined uranium ore. But a reliance on mined material inputs is hardly exclusive to the nuclear industry. Consider, for instance, the lithium mining required to produce electric vehicles. And as reported on the blog of The Union of Concerned Scientists,

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, about 12% of all silicon metal produced worldwide (also known as “metallurgical-grade silicon” or MGS) is turned into polysilicon for solar panel production. China produces about 70% of the world’s MGS and 77% of the world’s polysilicon. Converting silicon to polysilicon requires very high temperatures, and in China it’s coal that largely fuels these plants. Xinjiang—a region in China of abundant coal and low electricity prices—produces 45% of the world’s polysilicon.

Despite this, however, I would never dream of accusing pro-solar activists at COP events of being “shills” or advocates of “dirty” tech. That sort of selective calumny is reserved for nuclear.

I’m happy to report that this year, at COP27 in Egypt, nuclear boosters had a strong presence, ranging from high profile speakers on panel discussions at the pavilion of the International Atomic Energy Agency, to Canadian playwright Baba Brinkman’s freestyle rap about nuclear, and of course Bella the bear’s return. Nuclear can be said to have a seat at the table, even if at least half the table ridicules us or tries to ignore our presence. (That half includes the woman who called us “cringe” in Sharm El-Sheikh: Aruna Chandrasekhar, a journalist for the UK-based Carbon Brief website, which presents itself as “covering the latest developments in climate science, climate policy and energy policy.”)

Several years ago, Prince (now King) Charles said that “Planet Earth is a sick patient due to climate change.” By that metaphor, nuclear workers deserve to be seen as some of the medical specialists we need in the room to help stabilize the patient. You can shout at us, bully us, and demean us all you want. But we’re not going to stop showing up for evidence-based climate action.