Back in the year 2000, David Brooks made his name with the publication of his first book, Bobos in Paradise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There. Until that time, Brooks had been a journalistic journeyman, having put in stints at the City News Bureau of Chicago, the Wall Street Journal, National Review, the Washington Times, and the Weekly Standard. But Bobos in Paradise made him a star. In 2003, when the New York Times went looking for someone to replace retiring conservative columnist William Safire, Brooks got the job. Ever since, he has been one of America’s most visible and widely published pundits, with regular appearances on PBS’s The News Hour, NPR’s All Things Considered, a contributing-writer slot at the Atlantic, visiting professorships at prestigious universities, and even a TED talk, which he delivered back in 2019. And all of this came about because of a book filled with observations about America’s future that have turned out to be spectacularly wrong.

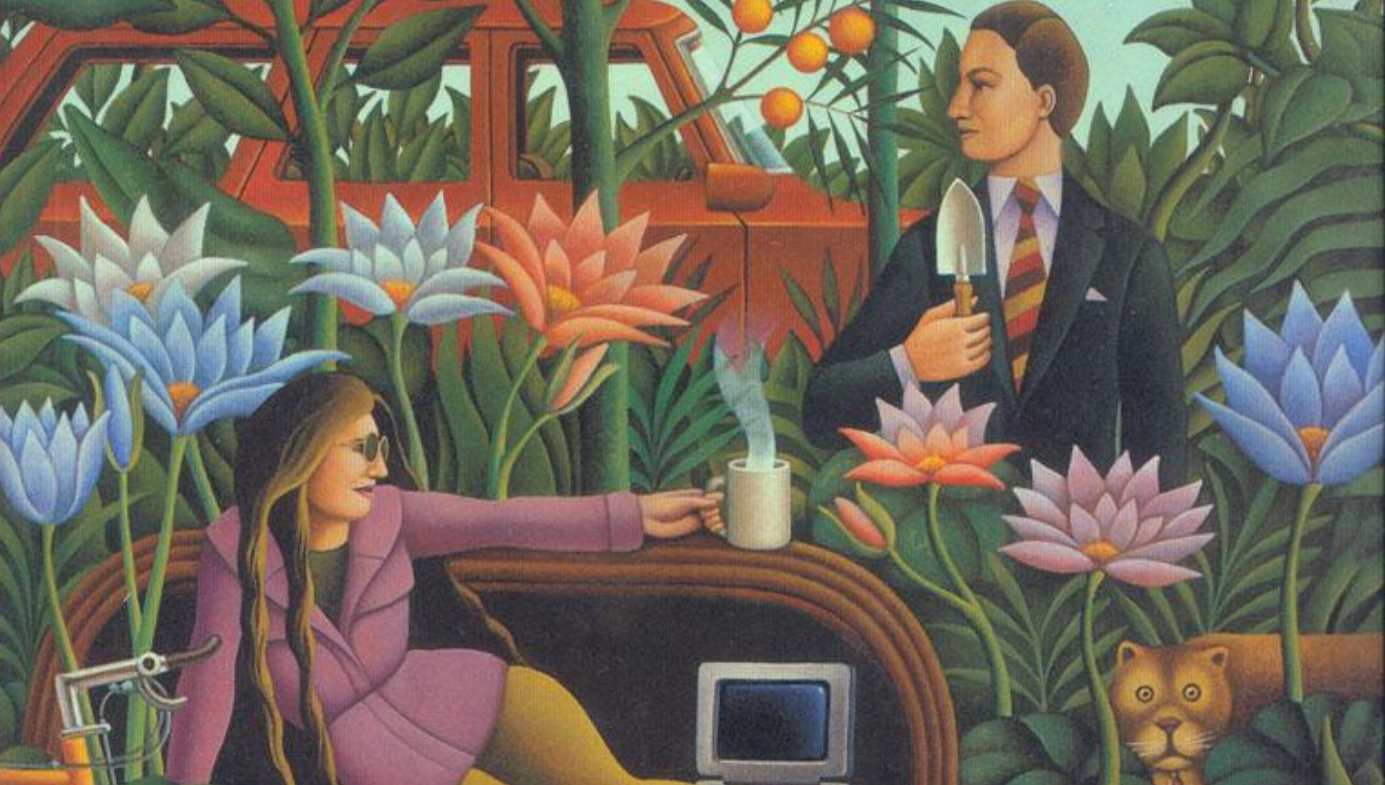

“Bobo” was Brooks’s term for an elite class of Americans who combined the bourgeois world of capitalism with the bohemian vibe of the 1960s hippie counterculture. His book argued that these well-heeled bobos—with their elite college degrees and prestigious positions in corporate America (or academia, or law, or medicine, or government, or the non-profit sector)—had changed America for the better and would continue to do so well into the 21st century.

If Bobos in Paradise were a child of one of the bourgeois bohemians it described, 2022 would be the year it graduated from college (although, in proud Bobo tradition, it would almost certainly go on to pursue a post-graduate degree). But the 2022 we live in is very different from the 2022 one might have anticipated after having read Bobos in Paradise back in 2000. I say this not to belittle Brooks. He is a smart and engaging writer and—back in 2000, at least—he was an upbeat pundit who eschewed much of the pessimism of the trade. But his optimism about capitalism and America’s moneyed elite has proven, in many cases, to have been misplaced. As the title implies, Bobos in Paradise is a book about a coming Golden Age of American meritocracy. That Golden Age never really arrived. Or if it did, it wasn’t quite the paradise that Brooks had anticipated.

In the book’s introduction Brooks wrote this:

These Bobos define our age. They are the new establishment. Their hybrid culture is the atmosphere we all breathe. Their status codes now govern social life. Their moral codes give structure to our personal lives. When I use the word establishment, it sounds sinister and elitist. Let me say first, I’m a member of this class, as, I suspect, are most readers of this book. We’re not so bad. All societies have elites, and our educated elite is a lot more enlightened than some of the older elites, which were based on blood or wealth or military valor. Wherever we educated elites settle, we make life more interesting, diverse, and edifying.

That passage hasn’t aged especially well. As documented in Batya Ungar-Sargon’s recent book Bad News, America’s elites had little interest in pursuing careers as newspaper reporters until the 1976 film All the President’s Men made the profession look glamorous and important. Up until then, many of the most storied reporters in American journalism had received little or no college education. Once the elites took an interest in journalism, they made American newsrooms far less diverse places. Oh, you can find a multitude of ethnicities and sexual orientations and genders at America’s top newspapers and magazines, but you’ll find almost no reporters who lack an elite education. Gone are the days when a smart high-school graduate like H.L. Mencken could get a job as a copyboy at the local newspaper and eventually work his way up to star reporter. Curiously, Brooks acknowledged this, writing, “The educated elites have even taken over professions that used to be working class. The days of the hard-drinking blue-collar journalist, for example, are gone forever. Now if you cast your eye down a row at a Washington press conference, it’s: Yale, Yale, Stanford, Emory, Yale, and Harvard.” But because those Stanford- and Yale-educated journalists include blacks, Jews, Asian-Americans, women, and gays, Brooks saw diversity rather than homogeneity.

Brooks’s claim that the Bobos are a lot more enlightened than previous elites doesn’t track with reality either. The pay gap between salaried employees and CEOs has grown exponentially since the Bobos came on the scene. In 2020, American CEOs earned an average of 351 times what they paid their typical employee. CEO pay has gone up a staggering 1,322 percent since 1978, according to the Economic Policy Institute. That doesn’t sound very enlightened to me.

Brooks identified the 1960s as the apex of American bohemianism, an era when antiestablishment sentiment ran riot (sometimes literally) and nonconformity was (paradoxically) the order of the day. He identified the 1980s as the apex of recent American bourgeois excess, an era epitomized by the “Greed is Good” ethos depicted in the film Wall Street. For some reason, he believed that elites of the 1990s had fused these two worldviews in a way that neutralized their worst traits and emphasized their best:

Out of that climactic turmoil, a new reconciliation has been forged. A new order and a new establishment have settled into place, which I have tried to describe. And the members of this new and amorphous establishment have absorbed both sides of the culture war. They have learned from both ‘the sixties’ and ‘the eighties.’ They have created a new balance of bourgeois and bohemian values. This balance has enabled us to restore some of the social peace that was lost during the decades of destruction and transition.

Brooks’s largest blind spot concerned the political ramifications of this supposed evolution in elite thinking. He believed these bobos would usher in a new era of less confrontational politics of compromise and cooperation. Since so many ex-hippies were now rich, and since so many rich people were now embracing a more bohemian aesthetic in their choice of clothing and food and music and so forth, he thought there would be a great deal of common ground between the two sides. Thus, wrote Brooks:

The politicians who succeed in this new era have blended the bohemian 1960s and the bourgeois 1980s and reconciled the bourgeois and bohemian value systems. These politicians do not engage in the old culture war rhetoric. They are not podium-pounding ‘conviction politicians’ of the sort that thrived during the age of confrontation. Instead they weave together different approaches. They triangulate. They reconcile. They know they have to appeal to diverse groups. They seek a Third Way beyond the old categories of left and right. They march under reconciling banners such as compassionate conservatism, practical idealism, sustainable development, smart growth, prosperity with a purpose.

This, Brooks noted, was a pretty good description of how the Clinton administration operated. Although Brooks was a Reagan Republican throughout the 1990s, he seemed to have been impressed by the way Clinton attempted to find a moderate center where Republicans and Democrats could unite. Brooks ignored the fact that Clinton was often foiled in these attempts by Republicans like Newt Gingrich, Bob Dole, Colin Powell, Tom DeLay, Dennis Hastert, and many others. Clinton even drew opposition from members of his own party, such as Senator Sam Nunn, who, along with Powell, opposed his attempt to allow gays to serve openly in the military. Brooks was writing in the late 1990s, shortly after the Republicans in Congress impeached Bill Clinton for lying under oath about an extramarital affair. All Brooks had to say about that, however was:

Many of Clinton’s attempts to reconcile opposing policies were unworkable. Nonetheless, the Clinton administration does leave behind an approach to politics that is enormously influential and is consonant with the Bobo age. This Third Way approach, neither neatly liberal nor conservative, neither a crusading counterculturalist nor a staid bourgeois, is a perpetual balancing act. And now if you look across the industrialized world, you see Third Way triangulators perched atop government after government. A few decades ago theorists predicted that members of the New Class would be more ideological than previous classes, more likely to be moved by utopian visions and abstract concepts. In fact, when the children of the 1960s achieved power, they produced a style of governance that was centrist, muddled and, if anything, anti-ideological.

That may have been true of the Clinton and Obama administrations, both of which at least made efforts at bipartisanship. But it certainly can’t be said to describe the Trump administration, nor for that matter the administration of George W. Bush. Nevertheless, Brooks argued that American politicians had settled on this less confrontational style because:

[it] is what appeals to affluent suburbanites and to the sorts of people who control the money, media, and culture in American society today. Today there are about nine million households with incomes over $100,000, the most vocal and active portion of the population. And this new establishment, which exerts its hegemony over both major American political parties, has moved to soften ideological edges and damp down doctrinal fervor. Bobo Democrats sometimes work for investment houses like Lazard Freres. Bobo Republicans sometimes listen to the Grateful Dead. They don’t want profound culture-war-type confrontations over first principles or polarizing presidential campaigns.

I’ve no doubt Brooks was being sincere about all this, but it’s hard to believe he could have witnessed the impeachment of Bill Clinton and envisioned a coming era of less polarizing presidential campaigns. In the 21st century, presidential campaigns have only become more polarizing and acrimonious. The loser in the most recent contest still hasn’t conceded defeat and his partisans tried to overturn the election results. Brooks can’t be blamed for not foreseeing every political development of the next two decades or so, but he seems to have paid no attention at all to the intense effort the Republicans made to destroy the presidency of Bill Clinton. Had he given more credence to that effort, and taken more seriously what fans of Fox News and Rush Limbaugh were hearing in the late 1990s, he might have been able to write with more prescience about what was in store.

Brooks envisioned an enlightened upper class bringing a commercial renaissance to middle America. Because bobos tend to eschew big-box stores and massive retail chains, he believed the future would bring to Main Street USA an endless blossoming of quirky, locally owned businesses selling us humanely sourced coffees and clothing made of hand-woven fabrics and books curated to meet the reading habits of the local population. The second chapter of Brooks’s book is titled “Consumption,” and it begins like this: “Wayne, Pennsylvania, used to be such a square town.” He goes on to describe a sleepy little upper-class burg where, for a century or more, change came slowly if it came at all:

But over the past six years or so, all that has changed. A new culture has swept into town and overlaid itself onto The Paisley Shop, the Neighborhood League Shop, and the other traditional Main Line establishments. The town, once an espresso desert, now has six gourmet coffee houses … Café Procopio is the one across from the train station, where handsome middle-aged couples come on Sunday morning, swapping newspaper sections and comparing notes across the tables on their kids’ college admission prospects. … A fabulous independent bookstore named the Reader’s Forum has moved into town where the old drugstore used to be (it features literary biographies in the front window), and there’s a mammoth new Borders nearby where people can go and feel guilty that they are not patronizing the independent place.

What Brooks failed to account for were bobos such as Jeff Bezos (CEO of Amazon) and Howard Schultz (CEO of Starbucks), whose ethos had nothing to do with the flower children of the 1960s and everything to do with Gordon Gekko’s assertion that “greed is good.” Today, the Reader’s Forum and Café Procopio are both “permanently closed.” Most of the other new independent businesses in Wayne that Brooks mentions—Your Gourmet Kitchen, Made By You, Zany Brainy, The Painted Past, Domicile, The Great Harvest Bread Company—are also listed by Google as “permanently closed,” or else they can’t be found at all. Even the massive Borders Group, which once operated nearly 700 bookstores across America, employing roughly 20,000 people, went bankrupt and was liquidated in 2011, in part because it couldn’t compete with Amazon’s brutal discounts on book prices.

The Great Harvest Bread Company was founded by Ed and Lori Kerpius. According to Brooks, “Ed got his MBA in 1987 and moved to Chicago, where he was a currency trader. Then, as if driven by the ineluctable winds of the zeitgeist, he gave up on the Decade of Greed stuff so he could spend more time with his family and community. So he and his wife opened the shop.” It appears that the winds of the zeitgeist weren’t as strong as Brooks thought they were. Another favorite destination for Wayne’s bobos was Fresh Fields, an upscale supermarket specializing in organic produce. What Brooks doesn’t mention is that Fresh Fields had been purchased by Whole Foods in 1996, and thus was part of a nationwide chain. Since 2017, Whole Foods has been a wholly owned subsidiary of Amazon.

Brooks also seemed to think that, sometime in the middle of the 20th century, America’s elite colleges went from being bastions of privilege to being places where anyone who excels in high school can find a place. He noted that, back in the mid-20th century, former Harvard President James Bryant Conant, along with Henry Chauncey, who helped create the Scholastic Aptitude Test, made elite colleges in America much more democratic: “[W]e are now living in a world created by Conant and Chauncey’s campaign to replace their own elite with an elite based on merit, at least as measured by aptitude tests.” Unlike the old elite, which was based on “noble birth and breeding … it’s genius and geniality that enable you to join the elect” of the late 1990s. Brooks described that elect as “an elite based on brainpower.” But even today, 22 years after Bobos in Paradise was published, 38 of the country’s most elite universities, including five Ivy League schools, draw more students from families in the top one percent of the economic pool than they do from families in the bottom 60 percent.

Harvard, wrote Brooks, “was changed from a school for the well-connected to a school for brainy strivers.” In fact, even today, 15 percent of Harvard’s students are the children of one-percenters. Only 20 percent of its students are the children of the bottom 60 percent. It seems as if money and connections still play important roles in one’s ascension to the Ivy League. As Brooks saw it, the new bobo establishment was setting a good example for those of us who were not a part of it:

[O]ver the past few years, this new educated establishment has begun to assume the necessary role of an establishment. That is to say, it has begun to create a set of social codes that give coherent structure to national life. Today, America once again has a dominant class that defines the parameters of respectable opinion and taste—a class that determines conventional wisdom, that promulgates a code of good manners, that establishes a pecking order to give shape to society, that excludes those that violate its codes, that transmits its moral and etiquette codes down to its children, that imposes social discipline on the rest of society so as to improve ‘the quality of life,’ to use the contemporary phrase.

And who did Brooks identify as the “quintessential figures of the new establishment”? Among others, he listed Charlie Rose, a renowned media figure whose career would tank in 2017 when eight women accused him of sexual misconduct (that number would eventually rise to 35); Doris Kearns Goodwin, a renowned historian and author who resigned from the Pulitzer Prize board when it was revealed that she had plagiarized numerous sources when writing a book about the Kennedy family; Bill Clinton, who even in 2000 nobody would have looked up to as a paragon of good manners; Steve Jobs, ditto; Lou Reed, for much of his life a heavy abuser of methamphetamines and alcohol who was once expelled from a Reserve Officers’ Training Corps program for pointing an unloaded gun at a superior’s head; George W. Bush, who would soon be putting together a presidential administration whose members would rack up 16 criminal convictions; and David Geffen, once ranked the second most polluting individual in the world because of his use of super-yachts. This hardly sounds like a group of people who eschewed the worst of the 1980s culture of greed and the worst of the 1960s culture of Free Love and drug abuse (although, to be fair, Brooks couldn’t have known about all of these transgressions in 2000).

Even more interesting than the list of people Brooks included in his new bobo establishment is the list of people he excluded:

Today’s educated elites tend not to bar entire groups, but like any establishment, they do have their boundary markers. You will be shunned if you embrace glitzy materialism. You will be shunned if you are overtly snobbish. You will be shunned if you are anti-intellectual. For one reason or another, the following people and institutions fall outside the ranks of Bobo respectability: Donald Trump, Pat Robertson, Louis Farrakhan, Bob Guccione, Wayne Newton, Nancy Reagan, Adnan Khashoggi, Jesse Helms, Jerry Springer, Mike Tyson, Rush Limbaugh…

And so forth. Just a few pages earlier, Brooks was telling us that “[T]his new establishment is going to be setting the tone for a long time to come, so we might as well understand it and deal with it.” Yet, his list of people who are explicitly rejected by the bobos begins with the name of a man who would be elected president 16 years later, and whose administration would be filled with exactly the kind of educated elites—Steve Mnuchin (Yale), Mike Pompeo (Harvard), Wilbur Ross (Yale), Jared Kushner (Harvard), etc.—whom Brooks assured us “do not engage in the old culture war rhetoric.”

The one man who probably did the most to put Trump in the White House was Steve Bannon, the chief executive of Trump’s presidential campaign, who has an MBA from Harvard. What’s more, among the politicians currently lining up to carry the banner of Trumpism into the future are J.D. Vance (Yale), Ted Cruz (Harvard), and Josh Hawley (Stanford and Yale). According to Brooks:

Members of the educated class are suspicious of vehemence and fearful of people who communicate their views furiously or without compromise. They are suspicious of people who radiate certitude, who are intolerant of people not like themselves. Bobos pull back from fire and brimstone. They recoil from those who try to impose their views or their lifestyles on others. They prefer tolerance and civility instead. Bobos are epistemologically modest, believing that no one can know the full truth and so it’s best to try to communicate across disagreements and find some common ground.

All of which sounds great. But it certainly doesn’t describe many of the educated elites who are most active in American politics, media, or business today. To Brooks, the problem with American politics was that poor and working-class people keep sending the wrong kind of politicians to Washington, DC.

The affluent suburbs send moderate Republicans or moderate Democrats to Capitol Hill. These politicians spend much of their time in Congress complaining about the radicalism of their colleagues from less affluent districts. They can’t understand why their liberal and conservative brethren seem addicted to strife. The less affluent polarizers rant and rave on Crossfire. They are perpetually coming up with radical and loopy ideas—destroy the IRS, nationalize health care. They seem to feel best about themselves when they are alienating others. All of this is foreign to the politicians from the Range Rover and Lexus districts. Like their Bobo constituents, they are more interested in consensus than conquest, civility than strife.

Brooks described bobo politics as “tepid,” but he didn’t mean it as an insult. “They never rise up for a fight,” he wrote. “They just go along their merry way, blurring, reconciling, merging, and being happy.” To this, he added:

Today’s Bobos seek to conserve the world they have created, the world that reconciles the bourgeois and the bohemian. As a result, they treasure civility and abhor partisanship, which roils the waters. … Thanks in large part to the influence of the Bobo establishment, we are living in an era of relative social peace. The political parties, at least at the top, have drifted toward the center. For the first time since the 1950s, it is possible to say that there aren’t any huge ideological differences between the parties. … Meanwhile, the college campuses are not aflame with angry protests. Intellectual life is diverse, but you wouldn’t say that radicalism of the left or right is exactly on the march. Passions are muted. Washington is a little dull. … The past 30 years have brought wrenching social changes. A little tranquility may be just what the country needs so that new social norms can form and harden, so that the new Bobo consensus can settle into place.

Twenty-two years later, it seems clear that what Brooks wrote about American politicians and their voters was true really of only the Democrats. In the last two presidential primary seasons, the Democrats were offered a choice between a radical left-winger, Bernie Sanders, and a boring old hack who would be happy with politics as usual. Both times, the overwhelming majority of Democrats made the boring choice. The same can’t be said of the Republicans. A handful of hardcore progressives—Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Rashida Tlaib, etc.—have made it to Washington in the past few election cycles, but their voices have been muted because the vast majority of Democrats, for better or worse, remain fairly moderate. But there is little that is moderate about the Republicans who have made it to Congress recently, the majority of whom voted not to certify the results of the most recent presidential election.

Brooks’s term “bobo” never really caught on like “yuppie” or “hippie” or “neocon” all did because the group it described never really formed a coherent whole. Yes, a lot of people graduated from elite colleges over the course of the last four decades or so. Yes, a lot of them became rich and influential. But they never really rallied behind a single political or communitarian vision. They didn’t reject showy materialism in anything like the numbers that Brooks claimed. They bought expensive houses and then expanded them into McMansions. They watched Sex and the City and then went out and bought expensive handbags and shoes and outfits like its protagonists. They went into politics but were not much more likely to run as Democrats than as Republicans. They were not conspicuously more virtuous than any previous American establishment.

When he wrote Bobos in Paradise, Brooks’s politics were slightly right-of-center. Nowadays, they are slightly left-of-center. He supported Joe Biden in the last presidential election. He now writes essays for the Atlantic with titles such as “The Terrifying Future of the American Right” and “The Nuclear Family Was a Mistake,” which sound as if they might be the work of a bomb-throwing radical but actually present a fairly nuanced view of contemporary American life. I’ve always liked Brooks’s work. And, for all its faults, Bobos in Paradise is still a very entertaining and often insightful book. Brooks has spent much of his life among well-heeled suburbanites and he writes about them with wit and sympathy. His biggest mistake was to write aspirationally.

Having watched Bill Clinton govern for eight years as a centrist who largely eschewed grand projects (particularly after the failure of his healthcare reform bill) and avoided large-scale foreign entanglements, Brooks optimistically hoped that this was how all future American presidents would govern. Alas, that hope came crashing down along with the Twin Towers on September 11th, 2001, less than a year and a half after the publication of Brooks’s book. Since then, for a variety of reasons, American politics have often been nasty, confrontational, and at times even violent.

In 2004 Brooks published a follow up called On Paradise Drive. By then, he seemed to realize that his utopian vision wasn’t going to materialize. This book also spent a lot of time describing the behavior of America’s educated elite, but this time around, Brooks conspicuously avoided making any broad sweeping predictions about the future. He didn’t retract anything he had written previously, but he was no longer pushing the idea that the Bobos had radically altered American politics for the better.

Rereading Bobos in Paradise recently, I couldn’t help thinking how much better my country would have been had Brooks been right—if America’s political class had rallied around his cry for a politics of tranquility and compromise. But in an age filled with dystopian fictions, it now reads like a utopian vision of a fictional America that never arrived.