Politics

Robert Trivers and the Riddle of Evolved Altruism

Survival of the fittest versus compassion and cooperation in evolutionary theory and politics.

Well before the advent of evolutionary theory, an altruistic tendency in human relations was noted by philosophers such as the revered Confucian scholar Mencius, who said:

The reason why I say that all humans have hearts that are not unfeeling toward others is this. Suppose someone suddenly saw a child about to fall into a well: anyone in such a situation would have a feeling of alarm and compassion—not because one sought to get in good with the child’s parents, not because one wanted fame among one’s neighbors and friends, and not because one would dislike the sound of the child’s cries. From this we can see that if one is without the feeling of compassion, one is not human.

More recently, the same was noted by the great economist Adam Smith, who argued that self-interested motivations can lead to productive behavior that benefits society and not just the actor. Even before he made this argument famous in The Wealth of Nations, Smith noted the power of altruistic motivation in his first major work, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), which opened with the following paragraph:

How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it. … That we often derive sorrow from the sorrow of others, is a matter of fact too obvious to require any instances to prove it; for this sentiment … is by no means confined to the virtuous and humane. … The greatest ruffian, the most hardened violator of the laws of society, is not altogether without it.

This altruism contradicts a superficial conception of Darwinian theory with its apparently brutal and selfish logic of “survival of the fittest.” However, a deeper understanding of evolution reveals that cooperation and various forms of altruism are not antithetical to Darwinism. Indeed, modern evolutionary theory has now explained the existence of a strong, direct, biological basis to altruistic behavior.

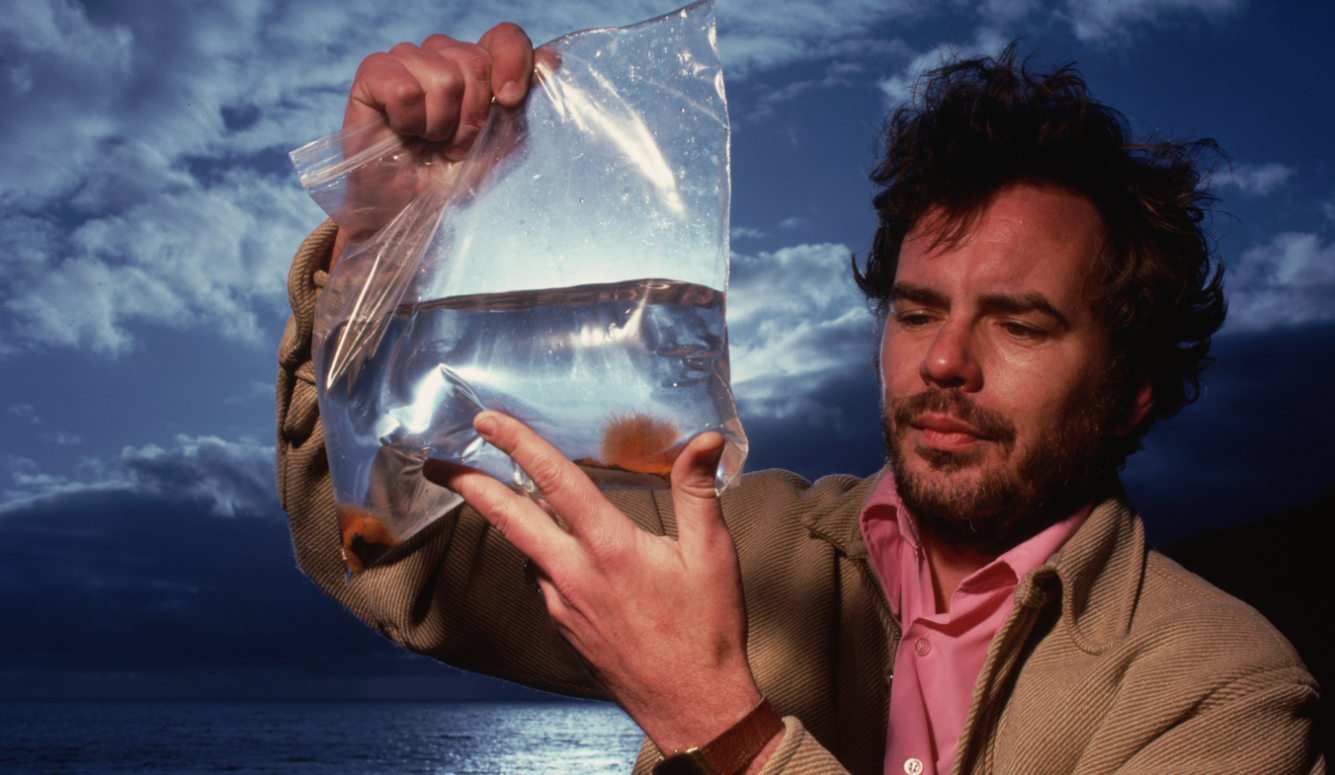

Altruistic behavior toward one’s offspring or other kin is not terribly puzzling since they are genetically related. More puzzling was the development of altruistic behavior toward unrelated others, which does appear to be antithetical to the basic, self-serving fitness interest that underlies evolutionary theory. However, Robert Trivers, in what quickly came to be considered a classic paper, developed the concept of “reciprocal altruism” which sought to explain the adaptive advantage of altruistic behavior toward unrelated others. He was even able to explain altruistic acts between members of different species which, of course, is an extreme example of a lack of genetic relatedness.

Trivers’s concept of reciprocal altruism is based on the notion that an altruistic act can at some point be returned. For example, Trivers described the relationship between certain host fish and unrelated cleaner fish. The cleaner’s diet consists of parasites removed from the host, which can often involve entering the host’s mouth. Cleaner fish are not common so host fish often return to the same cleaner who stays in one location.

Trivers described how a host fish will go through extra movements and delay fleeing when being attacked by a predator to allow a cleaner extra time to leave its mouth. One might assume that, at such a moment, it would be to the adaptive advantage of the host to simply swallow the cleaner. Instead, the host delays its departure and moves in a way that signals to the cleaner that it is time to get out of its mouth. This type of altruistic behavior seems to reduce the fitness of the host in two ways: (1) the delay in departing increases the chance that it will be eaten by a predator, and (2) it foregoes a meal of the cleaner. Yet Trivers was able to show that there is an adaptive advantage to this altruistic act—being able to have debilitating parasites removed in the future. We can safely assume that this kind of altruistic behavior is directly embedded in the motivational system of the host fish and is not learned.

Another paradigmatic demonstration of reciprocal altruism was provided by a study of vampire bats for whom starvation occurs within days of a failure to feed, and for whom the failure to feed is not an uncommon occurrence. Vampire bats engage in reciprocal food sharing (via regurgitation) between unrelated bats when the altruist is in good condition and the beneficiary is in serious need. Such a system is advantageous for the altruist because the altruistic act can be reciprocated when the need is reversed.

“Tit for Tat”: The cooperative winning strategy

Obviously, one cannot straightforwardly generalize from fish or vampire bats to humans. However, inspired by Trivers’s model, Robert Axelrod and William Hamilton employed game theory to demonstrate a general model for how a reciprocal strategy can outcompete more selfish strategies. They used a modified version of a game known as the Prisoner’s Dilemma, which has been extensively studied by social scientists.

This game involves a number of rounds of play in which each player makes a decision prior to knowing what the other has decided to do on that round. The game presents players with opportunities: (1) attempt to cooperate, (2) defect in order to protect oneself from a potential cheater, or to attempt to take advantage of the other player’s willingness to cooperate (to cheat), or (3) retaliate against a player who has defected in a previous round by refusing to cooperate with them. Successfully “cheating” a cooperator “paid off” the best (+5). Successful mutual cooperation was next (+3). Punishing a repetitive cheater or self-protecting refusals to cooperate with a cheater enabled the player to protect their own initial “investment” (+1). Finally, being cheated when one attempted to cooperate resulted in the worst outcome (+0). After each round the results were made known to the players.

A computer tournament was conducted of strategies submitted by game theorists in economics, sociology, political science, and mathematics. Though some of the strategies were quite intricate, the winning strategy (the highest score averaged against all challengers) was one of the simplest—a reciprocal strategy called “Tit for Tat.” Tit for Tat’s strategy was simply to cooperate on the first move and thereafter to do whatever the other player did on the preceding move. Thus, the strategy is to initially “announce” an intention to cooperate and then to let the other player know that cheating will not lead to a gain. Tit for Tat is quick to forgive no matter how many times the other player has cheated—just one indication of a willingness to cooperate from the other player leads Tit for Tat to try cooperation again. Axelrod and Hamilton noted that:

TIT FOR TAT is a strategy of cooperation based on reciprocity … it was never the first to defect, it was provocable into retaliation by a defection of the other, and it was forgiving after just one act of retaliation.

After circulating the results of the first round, 62 entries were received from six countries to compete in the second round. The winner of the second round, Tit for Tat! Axelrod and Hamilton went on to show how a “population” of strategies could be invaded by Tit for Tat. If high scores were indicative of differential success in survival and replication, after a number of rounds of play (a number of “generations”), Tit for Tat would replace the original strategies.

Using game theory to present a mathematical model of how, under certain conditions, cooperation between unrelated individuals could evolve, the authors were able to show that Tit for Tat could hold its own and win in a population of mixed strategies. In addition, they were able to show that once Tit for Tat became a significant part of the existing population of strategies, it would become an even more successful strategy as the reciprocal altruists would benefit from their cooperation while being able to protect themselves from cheaters who would be excluded from reciprocal exchanges. Indeed, they were able to show that selfish strategies would be unable to reinvade successfully.

Of course, human interactions are not this simple. It is not always possible to detect cheaters or to evaluate the degree of cooperation one is getting. Opportunities for cheating are widespread and there are other motivations outside of the reciprocal exchange system. For example, there are kin ties that are not dependent on reciprocity (though they too are influenced by it). Yet it is easy to think of numerous situations in which reciprocal exchanges benefit cooperators by providing advantages simply unavailable to individuals acting on their own. Particularly, as I have previously argued elsewhere, regarding “situations in which the cost to the altruist is significantly less than the beneficiary’s gain”:

If this sounds like a perpetual motion machine, where the output magically exceeds the input, consider just a few human examples such as a traditional barn raising, the act of helping an unrelated lost child find his or her way back home, and most forms of human charity. … People who can trade such acts will have a significant advantage over nonaltruists or those excluded from reciprocal arrangements.

Even more remarkable is the counterintuitive fact that—like vampire bats who would be in constant danger of starvation without reciprocal exchanges—people living on the verge of starvation often will share food with unrelated others. For example, consider regular, reliable reciprocal exchanges among non-kin residents in a Calcutta slum. In such circumstances, powerful friendship/reciprocal exchange systems can develop in and around competing systems of cheaters.

Peter Kropotkin (1842–1921), the revolutionary Russian anarchist communist, who developed a view of human nature based on mutual aid, also noted the vital importance of such exchanges under harsh conditions:

“You could not imagine” (a lady-doctor who lives in a poor neighbourhood told me lately) “how much they help each other.” … “If, in the working classes, they would not help each other, they could not exist. I know families which continually help each other—with money, with food, with fuel, for bringing up the little children, in cases of illness, in cases of death.

“The ‘mine’ and ‘thine’ is much less sharply observed among the poor than among the rich. Shoes, dress, hats, and so on—what may be wanted on the spot—are continually borrowed from each other, also all sorts of household things.”

Of course, this makes sense: during our mostly hunter-gatherer history when conditions could be extremely harsh there was no cushion. There were no FDIC-insured banks, no welfare, no unemployment, health, disability, nor life insurance. Given the physical dangers, it was unlikely that one could go through a normal lifetime without needing help from genetically unrelated friends and neighbors. It is only in times of surplus and physical security within a stable society that one can afford to live independently of one’s neighbors. Thus, today we see the demise of the “community” as affluence allows people to risk not even knowing the names of their neighbors, as is common in suburban America. Somewhat paradoxically, this suggests that the less one has, the more likely one is to be willing to share a greater portion of what one does have.

Another powerful demonstration of reciprocal exchanges in humans occurred during the early years of World War I in the trenches. Much to the consternation of the generals, the “disease of cooperation” between the opposing soldiers broke out all along the line. Stationed week after week and month after month in the same spot facing the same “enemy” the ideal conditions were present for the generation of reciprocal altruism. Soldiers shot to miss. Troops left the trenches and worked at repairing them in full view and within range of enemy soldiers while they passively looked on. Christmas was even celebrated together.

One striking incident occurred when in one area an artillery burst exploded sending both sides diving for cover. After several moments, a brave German soldier called out to the other side and apologized saying that his side had nothing to do with it, “It was those damn Prussian artillerymen.” Note that artillery is farther from the line and the mutual association with trading of beneficial acts (shooting to miss) was not available. Finally, the generals solved this thorny problem by ordering random raids (and shooting those who refused) that broke down the mutual trust and cooperation that had evolved.

The skeptic could argue that the human examples are anomalies, and of course, we don’t expect humans to behave like fish, vampire bats, reciprocal altruist monkeys, or relatively simple computer programs. However, the evolutionary analysis demonstrates the necessary prerequisites for the evolution of reciprocal altruism: (1) the ability of two organisms to behave in ways that benefit the other, (2) high frequency of association, (3) reliability of association over time, and (4) the ability of organisms to recognize and remember each other. This evolutionary line of thought poses a direct challenge to the classical psychoanalytic and religious notion that “guilt” is necessary for civilization. The prerequisites for the evolution of reciprocal altruism, that have been shown in other species to be capable of shaping extremely cooperative behaviors, are present in our species, and are possibly present to a greater degree than in any other species.

Trivers showed that altruistic behavior between human beings can confer a powerful adaptive advantage to the altruist thus producing increased selective pressure for further cranial development. As Richard Dawkins put it in his 1976 work, The Selfish Gene:

A long memory and a capacity for individual recognition are well developed in man. We might therefore expect reciprocal altruism to have played an important part in human evolution. Trivers goes so far as to suggest that many of our psychological characteristics—envy, guilt, gratitude, sympathy etc.—have been shaped by natural selection for improved ability to cheat, to detect cheats, and to avoid being thought to be a cheat. Of particular interest are “subtle cheats” who appear to be reciprocating, but who consistently pay back slightly less than they receive. It is even possible that man’s swollen brain, and his predisposition to reason mathematically, evolved as a mechanism of ever more devious cheating, and ever more penetrating detection of cheating in others.

Note that this view is consistent with conflict between self-interested individuals. However, we now understand such conflict within a larger social network of kin and reciprocal altruism. It is widely believed that human intelligence may have evolved primarily for social uses—to allow for the successful trading of altruistic acts (friendships, mutual parasite control [grooming], protective and/or aggressive alliances, economic [business] arrangements, etc.) without being cheated—as opposed to having arisen for tool manipulation.

Traditional conflict psychology sees altruistic behavior as a recent development brought into being after increased brain size began to lead to the formation of civilization. That is, civilization was made possible by increased intelligence, which led to pressure to control instinctual behavior, resulting in altruism. In contrast, evolutionary theory—and ethological evidence—suggests that altruism was probably an early phylogenetic development that in turn shaped the rapid development of the “swollen” human brain.

The presence of reciprocal altruism in other species and the dramatic forms it takes in human society have suggested to some scholars that the high degree of conflict that we see in our recorded history is not normal human behavior. These scholars argue that there were few pressures that selected for violent human competition and intergroup violence. The frequent appearance of these activities is then interpreted as an aberration, a deviation from true human nature. One of the earliest—and outside of evolutionary biology, one of the most influential—purveyors of this view was Peter Kropotkin, whose views are often held up in opposition to any suggestion that a tendency to engage in violent conflict is a powerful aspect of human nature.

Kropotkin’s mutual aid

Peter Kropotkin readily acknowledged that enormous amounts of conflict and violence have been characteristic of human relations. He insisted, however, that strong tendencies toward mutuality and caring are quintessentially human and dwarf egoistic motives. In order to explain human violence, he claimed that the vast majority of ugliness in human social relations is due to greedy actions on the part of the wealthy. Given this view, it is interesting to note that Kropotkin came from a royal family. He started life with the royal title of Prince, which he relinquished at the age of 12. In his youth, he was a page to Tsar Alexander II who freed the serfs in 1861. (In order to continue living on the land, the freed serfs, who comprised 38 percent of the Russian population, were required to buy land at exorbitant prices from the government, which had reimbursed the landowners.)

To understand Kropotkin, it is necessary to bear his context in mind. Kropotkin saw a majority of people around him going through periods of horrific—and not infrequently lethal—material deprivation. He then focused on trying to understand why, with enough wealth in the world for everyone to live healthy lives, so many were so deprived. Why were the lives of the masses so hard while human enterprise was producing enough material wealth for a significant minority (into which Kropotkin had been born) to live in excessive luxury? Thus, he focused on the distribution of material wealth as he attempted to bring a Darwinian analysis to bear on an understanding of human nature that would support his political convictions.

Described by Oscar Wilde as “that beautiful white Christ, which seems to be coming out of Russia … [one] of the most perfect lives I have come across in my own experience,” and by George Bernard Shaw as “amiable to the point of saintliness,” Kropotkin seems to have cared about others even when he became fired up and spewed righteous rhetoric calling for violent revolution. He despised the motives and behavior of those who attempted to maintain their wealth despite their knowledge of the plight of the less fortunate.

Kropotkin struggled to understand how things came to be as they are; surely, he reasoned, the greed around him while others suffered couldn’t be natural. Accepting Darwin’s theory of evolution as the proper frame within which to understand our nature, he struggled to find a way to reframe “survival of the fittest” into “mutual care and concern make one the fittest.” Animals that engaged in mutual aid, he argued, were more fit than those that didn’t. After providing numerous examples of mutual aid in humans as well as other species, consistent with what he wanted to believe, he concluded that mutuality is the true, fundamental essence of human motivation.

Though he acknowledged the reality of destructive human tendencies, Kropotkin insisted that human nature had been fundamentally shaped to place mutual aid and generous concern for others above all other motives. Because of this, he contended that the dire economic problems he saw around him were due to an avaricious minority that had somehow acquired ownership of most things (land, housing, machines, and “the means of production”). They were then able to use force to subjugate the many to accept this arrangement so they could continue to steal the fruit of the masses’ labor.

While one may agree with Kropotkin that the distribution of wealth is too often obscenely skewed by the ownership arrangements he described, he never adequately explained how and why the super-wealthy and the bourgeoisie—despite their essentially mutualistic human nature—had taken and then maintained such cruel control of things. How and why a violent revolution would eliminate the need for a leviathan to maintain a stable, large society is simply fantasized and insisted upon. Kropotkin claimed that once the full human tendency to engage in mutual aid is unleashed, somehow cooperation would obviate the need for force to prevent chaotic power struggles and the resumption of control of a society by a successfully violent coalition. Communist anarchy would then create a stable heaven on Earth.

This led Kropotkin to make a number of erroneous assertions about the inevitability of a glorious and imminent communist anarchy. Exiled to avoid imprisonment by the tsar, he returned soon after the Russian revolution only to die in disappointment a few years later as the harsh reality of Soviet communism began to crystallize. Nevertheless, he valiantly tried to sweep away the mountain of evidence in front of everyone’s eyes. Along with those who simply want more power and wealth, in any large social grouping (i.e., civilization after our hunter-gatherer period) there are always groups of people who also want to rearrange things because they feel aggrieved by the existing arrangements. And among the greedy, the power seekers, and the aggrieved, there are always those who would use force to rearrange things if there were no leviathan to stop them.

Thus, there is no group in power today that will be in power tomorrow if they are unwilling or unable to use force to maintain it. When a leviathan becomes weak and ineffective, the greedy, the power seekers, and/or the aggrieved will replace it with a new power structure. That’s history. Indeed, in Kropotkin’s day, those in power were acutely aware of the threat posed by Kropotkin and his fellow revolutionaries. And the power-holders frequently used force to maintain their position. Kropotkin was imprisoned in more than one country and had to flee more than once to remain free. He acknowledged that those who had attained power through the use of force were therefore often highly unpopular with those subject to that force. Because of this, those in power needed to maintain a monopoly on the use of force if they were to avoid being deposed. The communists would, therefore, have to use overwhelming force to seize power from the bourgeoisie and replace them with a communist, proletarian leviathan.

As Vladimir Lenin wrote in his 1917 work, State and Revolution:

The proletariat needs state power, a centralized organization of force, an organization of violence, both to crush the resistance of the exploiters and to lead the enormous mass of the population—the peasants, the petty bourgeoisie, and semi-proletarians—in the work of organizing a socialist economy. ... [T]he scientifically trained staff of engineers, agronomists, and so on ... are working today in obedience to the wishes of the capitalists and will work even better tomorrow in obedience to the wishes of the armed workers.

So, how then were the communists supposed to transition to an inevitable, peaceful, leviathan-free anarchy? Kropotkin naively predicted that, because of their natural mutualistic tendencies, the successful revolutionaries would only be willing to use force to create the conditions under which the state would no longer be necessary; at that point, the dominant, mutual-aid-producing human motivations would run their natural course and take over; peaceful anarchy would reign.

Christopher Boehm showed us that in small groups (hunter-gatherer tribes, small rural villages), with the occasional use of violence to remove bullies, this can work. Indeed, though there was plenty of violent raiding between neighboring tribes, a leviathan-free, intratribal, social arrangement appears to have existed throughout most of human history until settled agriculture and civilization began to take form somewhat more than 10,000 years ago. Hobbes argued that civilization needed to constrain our basic, violent, competitive nature to achieve stable social organization. However, he based his conclusion on what was known about post hunter-gatherer life when coalitions that specialized in violent competition had become viable. Only when a winner of the competition emerged and was able to acquire a monopoly on the use of force (and thus become the leviathan) would the violent competition for control cease and stability ensue. But our natural inclinations, shaped by hundreds of thousands (possibly millions) of years within hunter-gatherer tribes, may be more mutualistic than Hobbes’s “war of all against all.”

Kropotkin’s emphasis on mutuality may have been due to his accurate view that humans adapted over many millennia to relatively egalitarian tribal life and a longing to return to it, free of an oppressive leviathan. Lenin, too, seems to have distinguished between capitalist democracy (which he despised) and “primitive democracy in prehistoric or precapitalist times,” which is the form to which he predicted humanity would revert after the state with its leviathan “withered away” under communism. However, no known, large, civilized (i.e., post hunter-gatherer) society has existed and been stable over time absent a leviathan with a monopoly on the use of force.

But Marx and Kropotkin saw no need for a central government and therefore no need for it to be obliged to control itself. Instead, they argued for the use of violence both to overthrow the bourgeoisie and then for an indefinite period after the revolution during which a strong proletariat leviathan would be needed to create the socialism that would obviate the state. Lenin, whose violent revolution Kropotkin supported until he saw the murderous form it took, put the issue more clearly in State and Revolution:

The theory of class struggle, applied by Marx to the question of the state and the socialist revolution, leads as a matter of course to the recognition of the political rule of the proletariat, of its dictatorship, i.e., of undivided power directly backed by the armed force of the people. The overthrow of the bourgeoisie can be achieved only by the proletariat becoming the ruling class, capable of crushing the inevitable and desperate resistance of the bourgeoisie, and of organizing all the working and exploited people for the new economic system.

The proletariat needs state power, a centralized organization of force, an organization of violence, both to crush the resistance of the exploiters and to lead the enormous mass of the population — the peasants, the petty bourgeoisie, and semi-proletarians — in the work of organizing a socialist economy.

In the next chapter, Lenin continued:

The Communist Manifesto gives a general summary of history, which compels us to regard the state as the organ of class rule and leads us to the inevitable conclusion that the proletariat cannot overthrow the bourgeoisie without first winning political power, without attaining political supremacy, without transforming the state into the “proletariat organized as the ruling class”; and that this proletarian state will begin to wither away immediately after its victory because the state is unnecessary and cannot exist in a society in which there are no class antagonisms.

How then could Marx, Kropotkin, and Lenin believe that a group using force to maintain power (and thus inevitably unpopular among those subjected to that force) would have no enemies who would like to replace them? In fact, Kropotkin—who was a rather famous figure due to his writings and public presentations—was just such an enemy of the state. He acknowledged that the new proletariat owners would need to create a new leviathan to stabilize things, but he believed it would only be temporary.

This raises an obvious question. When would a small group using force to maintain control over a larger group ever be faced with a situation in which everybody was so happy with the arrangement that no one would be willing to use force to change it if they could do so successfully? Kropotkin believed that his thesis was consistent with the theory of evolution. In fact, he wrote an obituary for Charles Darwin in which he claimed that Darwin’s theories were “an excellent argument that animal societies are best organized in the communist-anarchist manner.” For Kropotkin, mutual aid was so essential to the survival of many species that it simply had to be more basic than self-serving motives that cause conflict and competition. This seemed like an obvious truth since violent conflict diminishes the overall survival and reproduction of the species.

Kropotkin based his belief on his own early formulation of what later became known as “group selectionism,” in which the observed mutuality is understood as having evolved “for the good of the species.” By the mid-1960s, however, group selectionism had been thoroughly discredited and, despite recent attempts to revive it, largely remains so today. Simply put, if a gene were to come into being that caused the organism to act “for the good of the species,” as opposed to acting for the good of the genetic material carried by the individual, it would very quickly be outcompeted by self-promoting genes. Pro-social tendencies would then have been an evolutionary dead end as predatory cheaters would take advantage of altruists and achieve greater reproductive success.

Kropotkin’s mutual aid versus Trivers’s reciprocal altruism

So, the old puzzle reemerged. If Kropotkin and the later group selectionists were wrong about the evolution of mutual aid “for the good of the species,” how could the evidence of considerable mutual aid be explained? This is where Robert Trivers stepped in.

Trivers, like Kropotkin and everyone else, has his own political convictions that could bias his theorizing. However, Trivers was gifted with a mathematical mind that was simultaneously acutely aware of the nuances of social relations. He was able to view social interactions from the perspective of the presumed genes that influence social behavior (the continued existence and proliferation of which are dependent on their calculable impact on their reproductive success). Using this perspective, he offered a series of piercing insights into the evolution of social behavior that, independent of any personal predilections and prejudices, have (unlike Kropotkin’s evolutionary theorizing) withstood the test of time and a high level of careful scrutiny.

In 2004, Steven Pinker wrote:

I consider Trivers one of the great thinkers in the history of Western thought. In an astonishing burst of creative brilliance, Trivers wrote a series of papers in the early 1970s that explained each of the five major kinds of human relationships: male with female, parent with child, sibling with sibling, acquaintance with acquaintance, and a person with himself or herself. … These theories have inspired an astonishing amount of research and commentary in psychology and biology—the fields of sociobiology, evolutionary psychology, Darwinian social science, and behavioral ecology are in large part attempts to test and flesh out Trivers’s ideas.

In contrast with Kropotkin’s political theorizing, Trivers was able to perceive the conditions necessary for the evolution of reciprocal altruism within a context that includes individuals ready to exploit others. Reciprocal altruism does produce the dramatic mutuality that Kropotkin described. However, unlike Kropotkin, Trivers didn’t suggest that loving mutuality was more basic to human nature than self-serving motives. Nor did he claim the opposite. Rather, he showed that reciprocal altruism evolved for the benefit of the reproductive success (inclusive fitness) of the individual actors, not for the good of the species.

Trivers’s new insight depicted an evolutionary arms race in the shaping of this set of human motivations. Extensive reciprocal altruism could only evolve with the simultaneous evolution of protections from cheaters. As protections against cheating became more sophisticated, so too did strategies of cheating. Since reciprocal altruism does provide an inclusive fitness benefit over purely individualistic strategies, the evolution of more effective cheating would in turn force the evolution of more effective forms of protection against cheating; and the cycle would continue. Because cognitive prowess enhances both the ability to cheat and the ability to detect cheating, this arms race also accelerated the growth of the human brain.

This vision of an arms race between exploiters and the potentially exploited is consistent with human history. It is also fully consistent with a theory in which natural selection shaped humans for the practice of coalitional aggression: Humans evolved the cognitive ability to use ideologies and other identity-forming narratives to form groups that violently vie for power. Such groups require a high degree of internal reciprocity and mutual aid if they are to thrive in violent competition with other groups. And for the greatest likelihood of success in actual combat, the highest levels of mutual support and cooperation are required.

In a society of sufficient size, there will always be individuals and groups willing and able to use force to take control of the larger group if breaking away is less desirable and there is no leviathan willing and able to stop them. This is why, in order for a large group to have a necessary and stable system of reciprocity, a leviathan must maintain a monopoly on the use of force.

Altruism and the evolution of the human cortex

Trivers’s presentation of reciprocal altruism suggests that such behavior and its underlying motivational system began to develop in the early history of our species, or even earlier (with our primate predecessors or even with their ancestors). As kin altruism is even more primitive (ancient)—some insects, fish, reptiles, most birds, and all mammals feed and/or protect their offspring despite significant costs—there may have developed a tendency to utilize the same cognitive and motivational systems employed for kin altruism for reciprocal altruism. First, among kin an admixture of kin and reciprocal altruism probably developed and this later extended to unrelated others.

Compassion or sympathy for one in pain (the empathic sharing of the experience of pain and the desire to alleviate the sufferer’s anguish) probably first evolved within the context of kin-directed behavior. This is so because in a kin relationship an altruistic act can increase the inclusive fitness of the altruist even if the act is not reciprocated. Therefore, the evolution of such behavior within kin relationships was not dependent upon a prior tendency for the recipient to reciprocate. The generalization of this behavior to reciprocal altruism among kin (and then to unrelated others) became possible when sufficient cognitive abilities were developed so that the altruist could distinguish between those likely to return the altruistic act (reciprocal altruists) and those unlikely to do so (cheaters).

Once powerful adaptive advantages could be obtained through participation in a reciprocal altruism system, there was increased selective pressure for the further development of the fairly complex cognitive abilities needed to engage in trading altruistic acts without being cheated. In addition to cognitive power, “civilizing” (social) tendencies were further developed. The following describes how reciprocal strategies could arise in a population and ultimately outcompete purely selfish strategies which would then be unable to reinvade the population.

As increased cooperation became possible, those early humans who were able to use guilt and shame to control their sexual and aggressive behavior—and to signal to others that they were likely to do so, which is one of the functions of guilt and shame—were able to attract altruistic actions towards themselves. Potential altruists were developing the cognitive ability to discern reciprocal altruists from cheaters. The cheaters could be identified, in part, by their selfish/instinctual behavior and their apparent lack of guilt, shame, or compassion. There was then an increased benefit from being able to participate successfully in a reciprocal altruism system which began to develop.

Like a snowball gathering mass and momentum as it rolls downhill, this led to additional selective pressure for the increased cognitive abilities which would allow the participant to comprehend the subtleties involved in the trading of altruistic acts without being cheated. As this developed, it further enhanced the benefits of an organized social system and signs of self-control and concern for others became even more important, for they ensured the individual’s inclusion in reciprocal exchanges. Once individuals could be identified who displayed the emotional and behavioral signs of an altruist and could be trusted to temper their selfish behavior, the ability to remain in and participate in a reciprocal system—which because of its developing stability, could function at a higher level of efficiency—became even more important.

Thus, the development of an emotion like guilt may be an important component of the reciprocal altruism system. It may have provided an important counterbalance to the pressures that selected for successful, undetected cheating. While it may have played a role in the further development of and maintenance of such a complex reciprocal exchange system, guilt was not the cause of it or the force that enabled it to arise in our evolutionary past. Guilt developed along with other sources of motivation toward trading altruistic acts and functioned as a signal to others that “here stands a reciprocal altruist.” The selective pressure shaping the development of guilt was the adaptive increase in one’s inclusive fitness due to a fuller inclusion in the reciprocal altruism system as opposed to exclusion based on being identified as a cheater.

While some altruistic behavior is thus clearly influenced by guilt, the reciprocal altruism system (human society) was not brought into play by the early development of guilt, which was the model proposed by Sigmund Freud in his Civilization and Its Discontents. Rather than guilt being thought of as the “cause” of altruism, it may be more accurate to think of altruism as the cause of guilt. This suggests that the early, traditional, individualistic (drive-based) psychoanalytic notion of guilt-tempered selfish drives cannot fully explain most altruistic, cooperative, and communal social behavior. The tendency toward empathic union with others and altruistic behavior may not be either a culturally learned response or a recently evolved cortical overlay in conflict with a more primitive biological core of self-serving sexual and aggressive drives. Rather, it is itself based on a very primitive biological core.

This topic will be developed further in the author’s forthcoming book on the evolution of violent tribalism.