Art and Culture

Two Hundred Years of Stendhal

2022 marks the bicentennial of the pseudonym’s transformation from literary dabbler into one of the greatest novelists of the modern age.

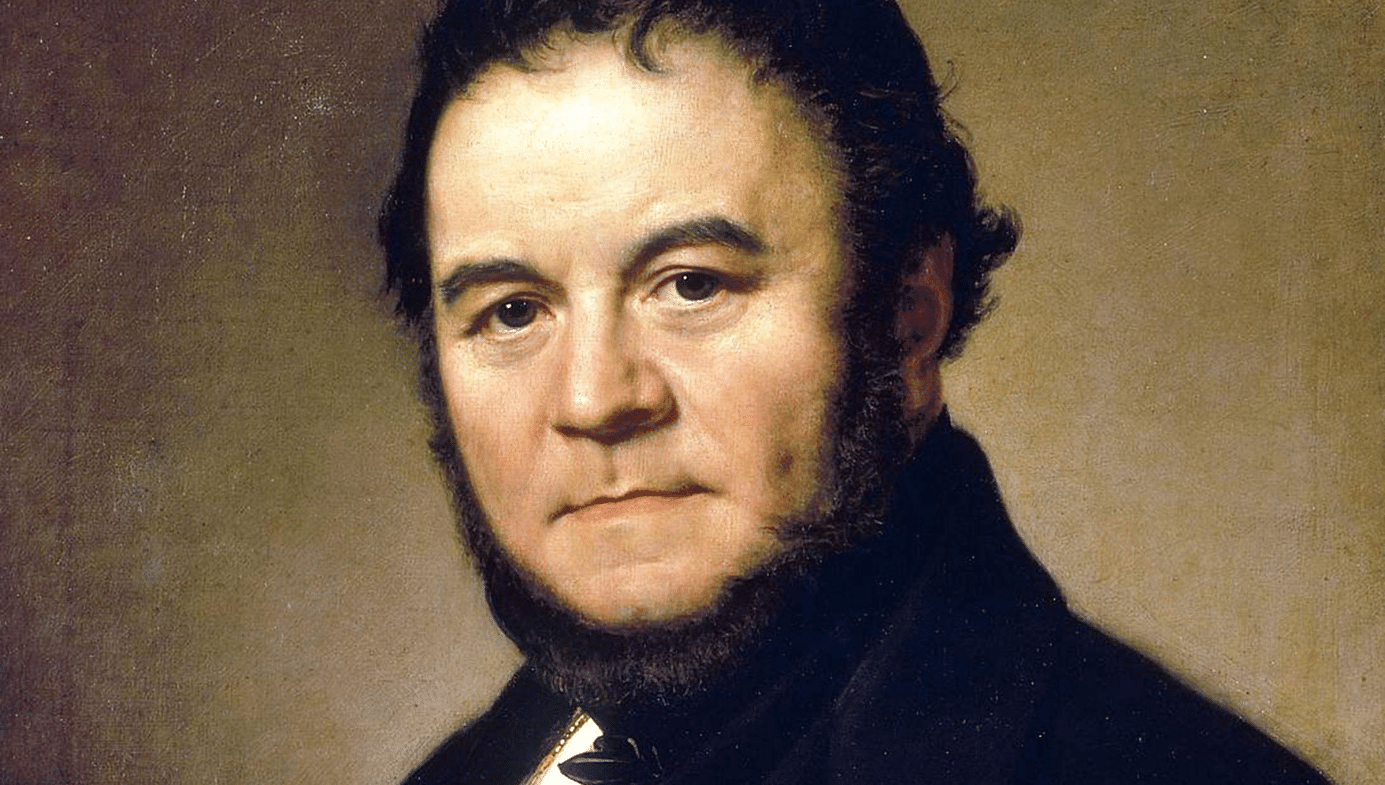

Two hundred years ago, Stendhal was born. Well, sort of. By 1822, Henri Beyle, the man we now know as Stendhal, was balding, fat, and pushing 50. Even the nom-de-plume was not born then. He had invented it a few years earlier by plagiarizing and misspelling—two Stendhalian trademarks—the name of a German town, Stendal, he had passed through as a 20-something officer in Napoleon’s army. Why Beyle settled on Stendhal is not clear. It was just one among the 200 or so pseudonyms he slipped in and out of during his writing life, ranging from Anastase de Serpière and Baron Pataut to Old Hummus and William Crocodile.

On the other hand, it is hard to imagine Polybe Love-Puff (yet another pseudonym) as the author of The Red and the Black. More importantly, it is equally hard to imagine Stendhal without Napoleon Bonaparte. The day after the 29-year-old Buonaparte—the Corsican native’s actual name—overthrew the revolutionary regime in 1799, the 16-year-old Grenoble native arrived in Paris to pursue his studies. From that moment, the lives of the two ambitious provincials became entwined.

So much so that when Bonaparte won a one-way ticket to Saint-Helena in 1815, having failed to save his empire at Waterloo, Beyle remarked, “I fell with Napoleon.” But not for long. In June 1821, after several years of self-exile in his beloved Milan, Beyle returned to Paris. Just as Napoleon’s coup had set the stage for Stendhal’s earlier arrival, Napoleon’s death preceded his return to the city by just a few days.

A coincidence, of course. But the sort that occurs in his novels and that points to deeper meanings. Like his idol, Stendhal fused Enlightenment rationalism and revolutionary romanticism. He became, in effect, the Napoleon of literature, overturning not a continent, but the conventions of fiction. Fiction, indeed. Towards the end of his life, Napoleon declared, “My life has been a novel!” Stendhal might have proclaimed, “My novels have become my life!” Unlike Napoleon, though, Stendhal not only found his calling, but also his self in his writing.

Upon the first Bourbon restoration in 1814, Stendhal looked for an exit. Though government spies tracked his movements, his life was not threatened. But his sanity was. The reactionary Bourbon court, dismissed by Stendhal as the “scum of the earth,” had sucked the air from Paris. As the narrator in The Red and the Black observes, “As long as one didn’t make jokes about God, priests, and kings … as long as one didn’t say anything in favor of Voltaire or Rousseau and, above all, as long as one never talked politics, one could discuss everything quite freely.”

The following year, Stendhal fled Paris for Milan, where he was determined to win a reputation as a writer. The seven years he lived there did wonders for his love of opera, but rather less for his hopes of literary fame. Stendhal remained a marginal literary figure, better known in Milanese salons than in Parisian bookstores. He had made a name—or rather his pen-names—by writing bowdlerized biographies and chatty travelogues. By 1822, though, the loss of Milan (the local Austrian authorities suspected Stendhal of ties to the nationalist Carbonari); the loss of Napoleon (who had ignited Italian nationalism); and the loss of hope in winning the heart of Métilde Dembowski (a Milanese beauty also suspected of Carbonari ties) led to the crystallization of his literary ambitions.

“Crystallization” happens to be a word Stendhal coined in De l’amour, his first proper book, published shortly after his return to Paris in 1822. Deeply impressed by this notion, he proclaimed the moment he conceived it a “Day of Genius.” He was right. Stendhal’s notion of crystallization has proved as lasting as, say, Socrates and Aristophanes’s descriptions in Plato’s Symposium. Rather than the desire to ascend to a transcendental idea or desire to mend with one’s lost half, however, crystallization is the desire to imagine the other as one’s beloved. Love is formed in the workshop of our imagination, becoming more real than any object hammered into existence in the workshop of an artisan or even of nature.

Take a bare branch, Stendhal observed, and place it in one of the caves outside Salzburg. Were you to return for the stick in a few months, you would not recognize it. Now encrusted with a coat of brilliant crystals, what had been bare wood has been reborn as an object of blinding beauty. So, too, with the cave of our imagination. We plant an image of another person inside it, and in time, it too bristles with crystals. This image, adorned with “a thousand further perfections, becomes your greatest pleasure.” Do you doubt these perfections are real? In reply, Stendhal would only sigh: clearly, you have never known love. Unlike most emotions, which “adapt to cold reality,” love shapes reality. The “miracle of civilization,” Stendhal announced, occurs in the crucible of passion, when “la chose imaginée est la chose éxistante.” Not something that seems real, mind you, but something—namely, your perception of another—that is real.

By “crystallization,” Stendhal meant what we experience upon falling in love with another person. This kind of love, he declared, “has always been for me the most important thing, or rather the only thing that mattered.” Heaven knows he was well practiced in this kind of alchemy, garbing with crystals a series of Italian women with whom he was mostly unsuccessful.

But it turns out that crystallization also applies to politics. Stendhal does not tell us this, but he shows it to us time and again in his fiction. In The Red and the Black, he portrayed the Ultras, those aristocrats more monarchist than the monarch himself, as fanatics whose passion to unmake a quarter-century of revolution, though objectively unhinged, comprised their reality. Convinced they could turn back time, they succeed only in convincing the hero, Julien Sorel, that they are ridiculous. “They are so afraid of the Jacobins,” he reflects. “They see a Robespierre and his tumbril behind every hedge.”

Yet the Jacobins, the mirror image of the Ultras, also repelled Stendhal. He despised the revolutionary passions that led from the glory of the Bastille to the gore of the Terror, and transformed the people into a mob that traduced the values of 1789. Lucien Leuwen, the protagonist in Stendhal’s unfinished novel of the same name, acknowledges the energy of the radical republicans, but also worries what their victory portends. Fiercely outraged by the miserable lot of the poor, he also fears a future where their Jacobinite leaders win political power. In such a society, he imagines, “men are not evaluated but counted, and the vote of the most ill-mannered worker counts as much as that of Jefferson.”

Though Alexis de Tocqueville had published the first volume of Democracy in America shortly before Stendhal’s death in 1842, there is no indication that the novelist had read it. Yet they share the same diffidence towards the ineluctable march of democracy as they did towards the inevitable retreat of the aristocracy. As such, both men make awkward company for those on both the political Left and Right.

Yet when it came to the world of politics, Stendhal was more severe than Tocqueville, treating all its representatives freely and equally with anything but fraternity. With the flagging of revolutionary energy, politics became a tawdry business where the good gives way to greed and the people become the means to power, not its end. No doubt, Stendhal shared the cynical attitude of Lucien Leuwen’s father, a successful businessman, who tells his son that all “governments lie all the time and about everything; when they can’t lie about the substance, they lie about the details.”

More ominously, the revolutionary impulse, no less than its reactionary counterpart, often leads to tyranny. Stendhal was a sincere republican, but a republican pas comme les autres. From childhood—or, at least, the childhood he portrays in his autobiographical works—Stendhal was allergic to tyrannies. Remarkably, in his personal writings, he emphasized his enduring hatred for his cold and authoritarian father, explicitly tying France’s revolt against the monarchy to his own rebellion against the patriarch. Indeed, when the 10-year-old Beyle learned of Louis XVI’s beheading in 1793, the adult Stendhal claimed he “was seized with one of the most fervent impulses of joy I ever knew in my life.”

Some biographers suspect Stendhal’s republicanism was not political, but instead psychological. How could they not, given his declaration that, “Every sort of tyranny revolts me, and I have no love for authority”? As one recent biographer, Jonathan Keates, suggests, Stendhal was less a man of the Left than a man of “ingrained antipathy to the status quo.” Like an American contrarian with an equally famous pseudonym, Stendhal refused to belong to any club that accepted him as a member. He decried authoritarianism and defended liberalism, but he also defended his right not to have anything to do with those who most benefitted from liberalism. As the narrator in The Red and the Black insists, the “tyranny of public opinion—and what an opinion!—is as stupid in the little towns of France as in the United States of America.”

Both nations had their share of stupidity then as they do now. But they also shared something else. In early 19th century France, as in early 21st century America, you might not be interested in politics, but politics were interested in you. This truth governs the lives of Stendhal’s fictional characters as much as it did his own life. The political events that pummeled the quarter-century stretching between the falls of the Bastille and Bonaparte were, in George Steiner’s memorable phrase, far more than temporal designations: “They stand for great storms of being, for metamorphoses of the historical landscape so violent as to acquire, almost at once, the simplified magnitude of legend.”

Befitting a contrarian, even when it came to his own practices, Stendhal always insisted that politics had no place in fiction. “The presence of politics in a work of literature,” he claimed, “is like a pistol shot at a concert.” Though often muffled, however, pistol shots ring out repeatedly in his novels. Then as now, men and women understood the world, and their place in it, through politics. This is no less true for Stendhal’s characters. But la politique, as Steiner suggests, often bled into la mystique. At no time in modern history was this more the case than during the rise and fall of Napoleon, and perhaps there was no individual in whose mind the facts and fictions of Napoleon’s career mixed so creatively than Stendhal.

Once upon a time, to be Bonapartist and republican was not at all paradoxical. On the contrary, it seemed perfectly logical. Stendhal was not alone in embracing the young man who had harnessed the nation’s revolutionary enthusiasm. The image of the dashing general who, rocketing from obscurity to renown, led his revolutionary army across Italy, liberating one city after another from the dead weight of monarchy, captured his generation’s imagination. The sheer force of energy embodied by the young Napoleon promised to sweep out the old and hoary world of hierarchy and authority and sweep in a new world of meritocracy and glory.

Unsurprisingly, it was a time when, as Stendhal later recalled, “we could love Napoleon passionately.” Yet his love, while fervent, was never foolish. The crystals with which he had coated Napoleon eventually cracked, revealing the egoistical, flawed, all-too-human being within. In his two unfinished works devoted to Napoleon, Stendhal repeatedly condemns his transformation from a “son of the revolution” into an “absolute despot” who, upon anointing himself emperor, “stole our liberty.” The tragedy of the Napoleonic Empire, Stendhal lamented, was that “religion came to sanctify tyranny, and all this in the name of the happiness of men.”

His disillusion deepened with the march on Moscow in 1812, when Napoleon led 700,000 soldiers—including 300,000 Frenchmen—onto Russia’s frozen killing fields, leaving most of them for dead a few months later. Commissaire Henri Beyle, one of only 55,000 French soldiers who returned home, led a convoy of 1,000 wounded soldiers to safety with a calm competence praised by other officers. (So calm, indeed, that during the retreat he read a copy of Madame du Deffand’s correspondence he had pulled from a burning house in Moscow.)

Stendhal later regaled listeners—including a profoundly impressed Lord Byron—with his detached and nearly clinical accounts of this appalling experience. Yet it was as if, in describing the horrors of war, he turned to the same narrative exigency he used to describe the wonders of love. “I am doing my best to be dry. I want to silence my heart, which believes it has much to say. I always tremble to think I have set down a truth, when I have only inscribed a sigh.”

Yet the experience harrowed and forever haunted Stendhal. It was an event, he later wrote with laconic lucidity, that “made me suspicious of the attributes of snow. Not because of the dangers I faced, but instead because of the awful sights of horror, suffering and extinction of pity. Cracks in the walls of the hospital in Vilna were stuffed with frozen pieces of human bodies. This picture is never far from my memory.” It also made him forever suspicious of politics, especially when it turns a single man like Napoleon into “our only religion.” Stendhal grasped that despotism is contagious, corrupting not just the soul of the despot, but also threatening that of the nation. This was true under the Bourbon and Bonapartist monarchies. Crucially, it held true under the Orléanist monarchy which, deftly capturing power in the confusion of the 1830 revolution, proved no less despotic and corrupting.

For those who came of age in this era, what were they to do? Be happy, answered Stendhal.

By happiness, Stendhal had something specific and, yes, serious in mind. Not Bobby McFerrin’s advice, but rather that we should face our lives and be honest. Le bonheur lies at the end of this activity, one which we can fully realize only in an open society. A closed society like post-revolutionary France, straitjacketed by social distinctions and conventions as arbitrary as they were absolute, seeks to prevent this most vital of pursuits. For those who do attempt this quest in such a society, such honesty entails death.

Take Julien Sorel, the 20-something hero of The Red and the Black who was so taken by the memory of Napoleon. On the eve of his execution—he has been sentenced to die for the attempted murder of Madame du Rênal, the one person he truly loved—he reflects on his heroic but failed effort, through the same force of energy embodied by his idol, to rise above his peasant origins and become master of himself and the hoary and hypocritical world of the restoration France. After a long night of relentless reflection, which leads him to dismiss the temptations of both religious faith and bad faith, Julien comes to terms with his life: “He felt himself to be strong and resolute like a man who sees clearly into his own heart.”

The critic Wallace Fowlie, one of Stendhal’s most sympathetic readers, claimed that his genius was due, in part, to his sympathy for his characters. He was, Fowlie writes, “literally inhabited by his characters,” discovering himself as he discovered them. What both they and their creator reveal is a truer meaning of happiness than we seem to hold. Stendhalian bonheur does not mean, as we tend to believe, success in work and love. Instead, happiness is to be had by overcoming our failures to find either one or the other.

And this can only be achieved by reasoning rightly and feeling deeply over these efforts. These efforts can be either those we or others have made, and those others could be either fictional or real. As the “Happy Few” already know, such distinctions, in the world of Stendhal, are without differences.