I joined Instagram in 2020. I posted one photo of a book and suddenly the words “Welcome to Bookstagram” appeared. I had been assigned a niche within minutes. Having always been a rather introspective, studious type, I was dubious about stepping into this alien world. But here, I was surprised to discover, was something for everyone, or so it seemed. Bookstagram is a corner of Instagram where serious readers hang out. While there are thousands of fiction “grammers,” I preferred to hang out in the nonfiction neighbourhoods, where people are consuming everything from the latest productivity bible to Nietzsche.

Bookstagram reminded me of Mean Girls, in which the school population had organized themselves into distinct “cliques.” There were the growth fanatics (predominantly male) who posted nothing but business and self-help books, all geared at maximizing self-efficacy, grit, and financial success. They told us all to read books like Rich Dad Poor Dad, The 4-Hour Work Week, Deep Work, Atomic Habits, Good to Great, Shoe Dog, amongst many others. There were the so-called “girlbosses,” who championed the roles of full-time professional, parent, and brand ambassador simultaneously: fierce ladies with leadership books in hand and babies on hip. They told us to go read books like Brené Brown’s Dare to Lead and Jen Sincero’s You Are a Badass.

Then there were the devoted aesthetes. I cannot say what they told us to read because I was always too mesmerized by their lavish displays to notice the titles of their books. They manufactured the most exquisite scenes of casual luxury—ornate linens strewn with grapes, a wine bottle, a baguette, and a candle perhaps, all surrounding the centrepiece: a prized review copy of the new destined-to-be bestseller. We are talking hours of exertion which has been disguised as a kind of lazy opulence. The final result is alluring, provocative, even sexy. But there is nothing remotely attractive about the labour it takes to get there.

And then there were the cerebral seductresses, who wrote in-depth literary critiques (as “in-depth” as is possible within Instagram’s caption limit of 2,200 characters) next to their beautifully clad bodies twisted into suggestive poses. I tried to squeeze myself into this category, paraphernalia trailing behind me everywhere—books and outfits (colour-coordinated, of course), straight-hair wigs, pretty hardbacks, props, camera stand, and my old second-hand Canon.

I figured out quite early on that no one was going to read my book reviews without some sort of bait. People tire of looking at book covers, no matter how artful the presentation. But an attractive woman with a book? Now that’s a welcome stimulus. The challenge was to pair my book reviews with the right bait—an impeccably curated aesthetic capable of catching the eye for long enough to gain more clicks into my caption (which was truncated at 125 characters). It was all about the clicks. I loved those clicks.

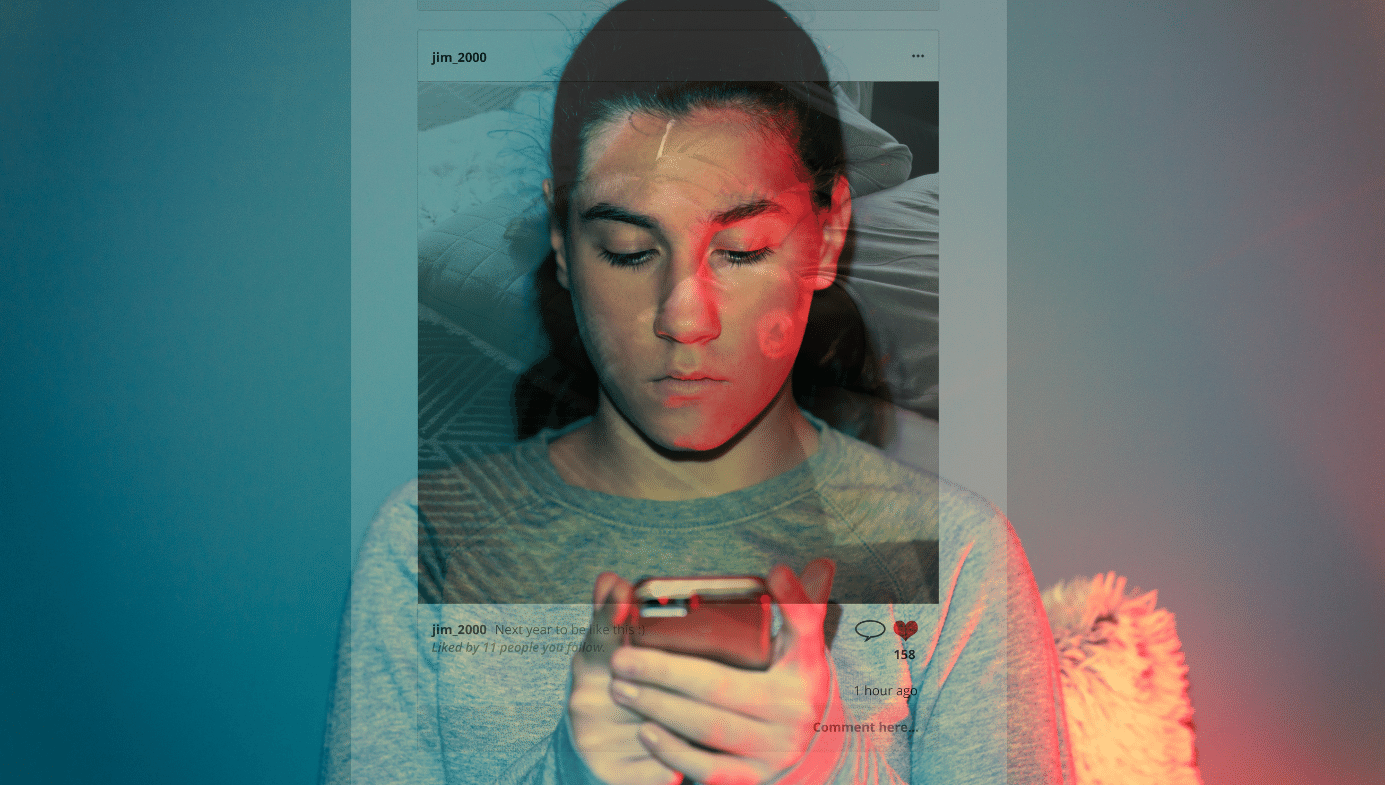

I was not alone in this love affair. According to a 2019 report by ThinkNow, 40 percent of US online users between the ages of 18 and 22 say that they are at least somewhat addicted to social media (this falls only slightly to 37 percent for the demographic aged 23–38). Effects are particularly pronounced amongst the young population, where it has been reported that roughly one-in-five US teens visits YouTube “almost constantly,” while 54 percent of teens say that it would be hard to abstain from social media. In light of these growing levels of dependence, we might reasonably ask how we can forge healthier relationships with the social media machine. What emerges when we dig deeper, however, is disenchanting. Invariably, we do not control the machine, the machine controls us.

Former professional poker player Liv Boeree has compared social media to a game, the object of which is to attain high visibility and the world’s attention. In order to gain a competitive advantage over the vast numbers of other players, we are each incentivized to follow certain strategies which—although they may provide short-term gains—put us at a collective disadvantage in the long run. Since quitting the game, I have become morbidly fascinated by “rules” of the game and their social and cultural implications. While there are innumerable rules to choose from, I have been particularly struck by the impact of five.

Rule 1: Don’t get caught in the act of being

Bookstagram marked the beginning of my digital self or avatar. Not unlike an alter-ego, she was the woman I aspired to be at all times but who I had to work hard to embody. Her charm lay in the illusion that she had appeared magically, as if by some spontaneous chemical reaction. But in fact, she was a fragile product, carefully stitched together using lighting tweaks, fake hair, and countless shots of the same pose. Regardless of this truth, I would have preferred that you watch her—she who had been pre-approved and rendered fit for public consumption—than my own private self.

Our avatars often enable a kind of subtle escapism. Scottish writer Andrew O’Hagan once remarked that, “we exist not inside ‘ourselves’ but inside neural networks.” This is a rather horrifying thought, but it also provides a degree of comfort when we are faced with the immeasurable burden of our own physicality. Bodies, after all, are profoundly burdensome things. They lock us inside a stable identity, tie us to some degree of inescapable accountability, and refuse to satisfy our desire for magical enhancements. Bodies are dead weight next to the seductive potentials of an infinitely malleable avatar. The digital persona allows us to escape—if only fleetingly—from bodies that are too small to contain our own radical imaginations.

Digital fantasies aside, there came a time in my Instagram “journey” (a popular turn of phrase, which gives the experience an eerie religiosity) when my digital avatar became a tyrant. She was always shrieking like a banshee for my attention. The shriek reached an ear-splitting pitch when an old friend of mine posted an unedited picture of the two of us in the “real world,” which appeared like fetid waste on my account. My face was bare, my kinky curls were on full display, and I was “ugly smiling”—Duchenne eye crinkles and all. My first thought was that my real self—that impostor—had been “outed.” In retrospect, this was more than a little melodramatic. At the time, however, to be caught in the act of spontaneous being was a catastrophe.

In her essay collection Animal Joy—published earlier this month—psychoanalyst Nuar Alsadir describes a scene from Jean-Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness, in which a man peeping through a keyhole hears the sudden creaking of floorboards and realizes that he has been seen. He experiences a dizzying switch of perspective, as his illusion of omniscience bursts and he sees himself as a mere object subordinated to the gaze of some anonymous onlooker. Alsadir writes:

The man imagines that the person who has seen him peeping through the keyhole knows him as he cannot know himself—knows him, in fact, better than he knows himself. He can now know himself only by reading the other’s knowledge, can see himself only through the gaze of the other. This transformation from being a subject with agency (the one doing the looking) to an object in another’s world to be evaluated (What do they see?) results in what Sartre calls existential shame—the shame of having been caught in the act of being who you are.

Sartre’s “existential shame” is of a special variety that we—avid scrollers—know all too well. It is not the shame that results from our own folly or some list of moral infractions that we guard close to our own chests. It is the shame that arises out of the fact of our own being. It is the small voice that says—in the midst of our frenetic social performances—I am ashamed of what I am.

If we are being radically honest, it is not that we are ashamed of who we are inside our own secluded selves. It is that we are ashamed of what we are when filtered through the minds of other people. (Perhaps this accounts for our growing obsession with face filters and editing apps.) Here, we are subjected to the most ruthless of transformations and distortions. And of course, we have no control over what is left once this evaluative process has taken place. That realization breeds a sense of powerlessness and dependency: what you are belongs not wholly to yourself but to the person who is watching you. In this way, much of our shame depends on the presence of other minds—or in the contemporary context—other followers. Social media’s answer to alleviating Sartre’s existential shame is to avoid getting caught in the act of being.

Rule 2: Shut up and behave inside the panopticon

Living inside Instagram or Twitter is vaguely analogous to life inside a virtual panopticon (which further exacerbates the human dilemma of existential shame). The original panopticon, comprising a ring of prison cells surrounding a central watch tower, was certainly less glamorous than its digital analogue. It was based on the general principle that people tend to modify their behaviour—in the direction of that which is considered pro-social and normative—when they think that they are being watched. When social reformer Jeremy Bentham designed this institutional model in the 18th century, the aim was to maximize social control using the fewest number of guards possible. In fact, no one even needed to occupy the watch tower. The mere perception of universal surveillance was sufficient to generate the kind of paranoia that leads to self-censorship and social conformity.

While our online habits and preferences are continuously tracked for the sake of targeted advertising, it is surveillance by our social media followers that appears to have the most notable psychological and behavioural impact. We play to our audience when we know they are watching us: we swagger, we flaunt our accomplishments (and our bodies), we curate our self-image, and most importantly, we try our utmost to behave. In this context, “good behaviour”—which is so often the price of online popularity—is behaviour that aligns with the accepted norms, values, and expectations of our society.

With all this tailoring, one might be tempted to declare that social media has become an identity project tied to acts of tightly regulated performance rather than those of spontaneous being. In a 2010 New York Times article, entitled “I Tweet Therefore I Am,” American author Peggy Orenstein writes, “Each Twitter post seemed a tacit referendum on who I am, or at least who I believe myself to be.” When there is a high risk of punishment for “misbehaviour”—which apparently, we can interchange with the term nonconformity—surveillance motivates us to monitor and tweak our digital identities. One inappropriate comment or poorly timed remark can haunt you for the rest of your life, thanks to the global, digitalized phenomenon of what has come to be known as cancel culture.

It is commonly understood that when acting as anonymous members of a group, human beings are more likely to behave in malign and socially destructive ways due to the diffusion of individual responsibility. In the digital world, where we can hide behind aliases, the same tendencies emerge. Here, we can mock, bully, and threaten heretics with impunity. You can call me a trendy refusenik for staying away from Twitter, but the truth—that it was an act of self-preservation—is a lot less sexy. As much as I admire the courage of the free thinkers and the iconoclasts who offer themselves up like hamburger meat to a pack of voracious lions, I would rather do at least some of my thinking in private.

Life inside the panopticon influences not only our external behaviour but also the distribution of public opinion. In the midst of watching and being watched, we begin to learn—often at an unconscious level—which opinions and views are met with public approval. Naturally, this affects our willingness to express our own personal opinions, especially when it comes to controversial political and social ideologies. On one hand, we are motivated to hide any seemingly unpopular or aberrant ideas to protect ourselves from social isolation. On the other, we are encouraged to noisily proclaim those opinions which find strong public support. This establishes what German political scientist Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann called the “spiral of silence”—a model of mass communication developed in 1974. The danger of this kind of phenomenon is that it seems to erode our concept of the democratic. The opinion of a minority—when defended assertively enough and amplified through the right social media—may be perceived as the majority.

Social media, which rewards certain opinions with hypervisibility while punishing others, appears to be the optimal spiral-of-silence machine. Sometimes, we are driven to swap our least popular yet most intelligent ideas for more “sanitary” ones, absent an exceptionally tough skin. These sanitized substitutes for candour have often been pre-digested for us by the masses. More often, however, we simply shut up.

According to 2021 Pew data, the majority (70 percent) of US social media users say that they never (40 percent) or rarely (30 percent) post about political or social issues. Their top reasons for avoiding these topics include concerns about their shared views being used against them in the future and not wanting to be attacked for these views. Meanwhile, on Twitter—journalists’ social-media platform of choice—the latest results reveal that in the US a minority of users (25 percent) produces 97 percent of all tweets. For more than half of the US Twitter population (54 percent), concerns about future repercussions (being called out publicly) inform each decision about whether or not to share content. Large numbers (53 percent) are influenced by who can see the post, while many consider whether the post will or will not reflect positively on their own public image (49 percent).

In Discipline & Punish, French philosopher Michel Foucault wrote that the chief effect of the panopticon was “to induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power.” Foucault may be spinning in his grave as the social media machine churns. But a small part of me enjoys the idea that if he were resurrected, he would join Twitter and rally his “tweeps” to action with a stream of erudite 280-character polemics against technological surveillance. There is a certain irony to harnessing social media for such comparatively noble goals. Regardless of the intelligence of the social commentary or the humanitarian value of the political resistance, every tweet, like, comment, and share oils the machine, which was designed not to promote user wellbeing but to maximize profit. On the former Vox Media podcast “Too Embarrassed to Ask,” virtual reality pioneer and tech critic Jaron Lanier makes the point that all energy injected into the system—regardless of whether it is hateful or positive—is used as fuel to keep the system alive:

[O]ften times when people think they’re being productive and improving society on social media, actually they’re not because the part of the social media machine that’s operating behind the scenes, which are the algorithms that are attempting to engage people more and more and influence them on behalf of advertisers and all of this, are turning whatever energy you put into the system into fuel to drive the system. And it often is the case that the fuel you put in is better driving the reaction than the original.

Rule 3: Stay inside the dopamine loop

The digital universe can be a vehicle for instant validation (provided you are thinking the right thing at the right instant). Playing to the crowd supplies a fast, cheap hit of dopamine like no other. After sharing a positive statement or a selfie taken from just the right angle, we leave the stage with a post-performance glow. It is not long before this glow has morphed into timorous anticipation, and we are back again, asking, “Did anybody like it?”

Inside this echo chamber, where our own thoughts, opinions, and preferences are reinforced, the answer is invariably yes! What is perhaps most alluring about this whole dopaminergic feedback loop, especially for creatives, is that the answer is almost always immediate. In a 2019 Guardian article exploring authors’ entanglements with social media, Matt Haig confesses his love for this form of instantaneous feedback—a much-sought-after “short term hit of recognition”—in contrast to the “glacially slow, long-form” task of book-writing.

Regardless of all our noble causes and reasonable motivations, the fact remains that adding fuel to the system simply feels good. Too good, some might say. In a 2021 Business Insider article, Peter Mezyk—developer and head of the international app agency Nomtek—reveals that social media belong to a highly addictive app category known as “painkiller apps.” Unlike “supplement apps,” which we use to solve specific problems on a sporadic basis (for example, banking and translation apps), painkiller apps do not fulfil any clearly defined need. Instead, they incorporate a “behavioural design” which satisfies the three criteria necessary to build a strong habit in its users: motivation (you associate the app with a fast dopamine hit), action (you can open the app with a single click), and trigger (your phone just vibrated with a new notification).

This three-pronged approach is based on the Fogg Behaviour Model developed by Stanford professor BJ Fogg. Addictive, profitable, and detrimental to the health of its users, the algorithmic design of social media has been compared to the incentives and urges manipulated and satisfied by tobacco companies. “It was only a matter of time before I started to notice the parallels between my drinking and my Instagram use,” writes American author Laura McKowen in a 2021 New York Times article. The similarities in addictive behaviour are stark:

“I’ll only use social media at set hours” became my new “I’ll just drink on weekends.” I tried to find ways to make Instagram a less toxic force in my life by using a scheduling app and not reading the comments, but every time that failed, I felt more defeated, powerless, and stuck. Just like with alcohol.

McKowen quit the app (followed by one short relapse) in 2021, concluding that “the buzz of fear in my stomach, the clutch of anxiety around my throat, the endless procession of negative thoughts ... [were] simply not worth it.” Drastic as this moratorium might seem, it echoes the sentiment of other creatives who struggle to moderate their social-media use. Nigerian writer Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀ has confessed that she alternates between cycles of “binge[ing]” and “[going] cold turkey” on her social-media accounts. She has even resorted to hiding her phone—the one with all the apps on it—in the wardrobe while she writes. She admits that she has not “found a way to use social media and still be reasonably productive.”

Despite the universal challenge in finding that elusive social-media/life balance, is going cold turkey really the only way? A randomized control trial, published earlier this year in the journal of Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, suggests that periods of abstention could provide the optimal result. The trial recruited 154 volunteers (with mean age of 29.6 years) divided into an intervention group—instructed to abstain from social media use (Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and TikTok) for one week—and a control group, who were given no such instruction. After one week, results showed “significant between-group differences” in wellbeing, depression, and anxiety. While researchers found that limiting time spent on Twitter and TikTok led to significant reductions in depression and anxiety, the most notable improvements in mental health resulted from taking a complete hiatus. It appears therefore that the greatest increase in our levels of happiness comes from stepping outside the dopamine loop.

Rule 4: Consumption trumps creation

Addiction to social media is not just about the loss of happiness and productive output (certainly, both are important symptoms), but about the loss of our attention. A study in the Journal of Communication found that 75 percent of screen content is viewed for less than a minute. The same study reported that, on average, we switch between screen content every 19 seconds, driven by a neurological “high.” Switching between different social-media apps and media channels—all competing for our attention—drains our overall cognitive capacity, and hence our moment-by-moment potential to engage in what computer science professor Cal Newport calls “deep work.” The latter is the source of our most impressive creative output.

Newport likens this fracturing of our attention to the loss of individual autonomy. In his 2019 bestseller Digital Minimalism, he writes:

[Social media apps] dictate how we behave and how we feel, and somehow coerce us to use them more than we think is healthy, often at the expense of other activities we find more valuable. What’s making us uncomfortable … is this feeling of losing control—a feeling that instantiates itself in a dozen different ways each day, such as when we tune out with our phone during our child’s bath time, or lose our ability to enjoy a nice moment without a frantic urge to document it for a virtual audience.

For the creative individual, this loss of control reveals itself the moment they realize that their attention—fragmented into a zillion pieces—is too weak to lend itself to that golden state of flow. Hungarian psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi describes flow as the state of total absorption in an activity for its own sake. This is a state in which both the ego (or sense of self) and our concept of time tend to disintegrate.

Naturally, the flow state draws on our capacity to detach from our social environment—along with its constant stream of positive and negative feedback—for just long enough to produce something of substance. It demands that we let go, at least temporarily, of our own self-consciousness and the neurotic compulsion to check and recheck the metrics—number of likes, tags, pinned comments, reshares, follower count, and so on. Flexing our thumbs as opposed to our creative muscles, social media often primes us not for creativity but for passive consumption.

Alas, our most radical attempts at self-restraint—including the banishment of our smartphones to the wardrobe—often fail to resolve the dilemma of our fractured attention. Even after we have dutifully disabled all social-media notifications and switched off the incessant vibration, we are still less likely to enter a state of productive immersion in our activities. Just the mere presence of a smartphone—turned off and face down on our desks—has been found to significantly reduce both our working memory and problem-solving capacity.

Rule 5: Don’t think. React.

I was first seduced by Twitter by the ease with which one could remain alert to what was going on in the world, and by the opportunity to become an active social critic. What’s not to like about the vision of a digital room of thinkers all swapping ideas like baseball cards?

It turns out, however, that the vast majority of social media does not reward thinking. The effort of thinking has gone out of vogue, while the reptilian act of reacting has never been more widely celebrated. Word and character limits box you into the kinds of punchy unqualified statements which—while they make great headlines—are terrible dialogue openers. Despite your best intentions, the substance and meaning of your short-form communication—which necessarily stamps out nuance and depth—is too often lost in the wave of combustible reaction that inevitably results. It seems that when it comes to social and political commentary, character count matters.

Online social networks like Twitter are optimized not for thinking but for reaction. This is largely due to the fact that anger feeds the machine in a way that reasoned debate does not. The machine is excellent at manufacturing moral outrage and political polarization by bifurcating society into opposing groups: black vs. white, liberal vs. conservative, Republican vs. Democrat, male vs. female. A study published in the journal of Psychological and Cognitive Sciences found that the presence of moral-emotional language (such as “hate”) increases the online spread of political messages by a factor of 20 percent for each additional word. Another more recent study shows that mention of a political out-group increases the likelihood of a social-media post being reshared by 67 percent—an effect which was stronger than that produced by negative affect language or moral-emotional language. It appears, therefore, that the expression of hatred, outrage, and out-group animosity are some of the key determinants of social media engagement.

A 2017 Guardian article reports that Zadie Smith abstains from social media in order to reserve her right to be wrong: “I want to have my feeling, even if it’s wrong, even if it’s inappropriate, express it to myself in the privacy of my heart and my mind. I don’t want to be bullied out of it.” She has voiced her concern about the volatility of people’s thinking inside a machine powered by rage:

I have seen on Twitter, I’ve seen it at a distance, people have a feeling at 9 am quite strongly, and then by 11 have been shouted out of it and can have a completely opposite feeling four hours later. That part, I find really unfortunate.

There is something to be said for making our minds up about an issue in private, outside the virtual panopticon. Good thinking, just like good writing, requires an incubation period. This is the time in which fragile, not-yet-fully-formed thoughts should remain hidden from the incendiary influence of public reaction. It takes an inordinate amount of energy to think for oneself and even greater energy to have an unpopular thought in defiance of the demand for social conformity. If you air your thoughts before they have reached stable maturity, there is always the risk that they will lose their shape—buffeted by demands for political correctness and sanitization—and hence their potential to make an original contribution. In the words of Mark Twain: “Whenever you find yourself on the side of the majority, it is time to pause and reflect.”

In the foreword to her 2009 essay collection Changing My Mind, Smith declares that, “ideological inconsistency is, for me, practically an article of faith.” Her assertion highlights an important aspect of human reflection. Deep thinkers grow into new thoughts and viewpoints just as they slough off old ones, in a continual process of evolution. But regardless of this natural process, many social media users have been forced to ossify inside the words that they uttered five years ago, as though change were not a property of being human.

My desire to think in private—outside of the oppressive burden of self-consciousness—was part of what motivated me to step away from social media (or, depending on your perspective, to become a Luddite). Reluctant to give it all up instantly, I experimented with slowly loosening the stitches that held my avatar together. A little unravelling was all it took—finally, I was free of the rules of the game.

Reclaim the right to exist

I quit social media to reclaim my right to exist—spontaneous and unfiltered. In Animal Joy, Alsadir—borrowing from the French professor of theatre and master clown Philippe Gaulier—defines beauty as “anyone in the grip of freedom or spontaneity.” This evokes a state which contrasts sharply with that of being shackled to the normative expectations, desires, and fetishes of a large audience.

This right includes the freedom to be an imperfect conformer—to “misbehave” and even to be outrageously inappropriate within the privacy of one’s own mind. Here, controversial viewpoints and unpopular thoughts run amok like unruly toddlers. So long as they can play freely, I do not have to contain the dissonance of an impeccably made and beautifully restrained avatar, whose sanitary opinions were borrowed from somewhere else.

Sometimes, these unruly infants find their way into my writing, but here, in long-form, they are not truncated by character limits designed to optimize reaction and eliminate nuance. Outside of the walls of social media, I relish the creative licence to take up space—the unapologetic literary equivalent of “manspreading.” This act of creation is made possible by attention that has not been splintered across multiple devices and social apps. And it has been enabled by the kind of old-fashioned slow thinking that fails to meet today’s criteria for “edgy” or “hip.”

I feel liberated, nonetheless. I relish that period of incubation when my thoughts and ideas grow outside the social demands for appropriateness and conformity. (Being human, I am occasionally tempted to dump some barely formed “insight” into the machine, until I see that it is already clogged with lukewarm, half-baked thoughts.) Like Zadie Smith, I relish the right to be wrong and to change my mind for what I hope are many decades to come. But most of all, I relish what I consider to be sacrosanct: the autonomy of the private self. When you opt out of the game, you discover that your own boundaries do not have to be so ruthlessly policed and interrogated.