Arts and Culture

The Striver’s Curse

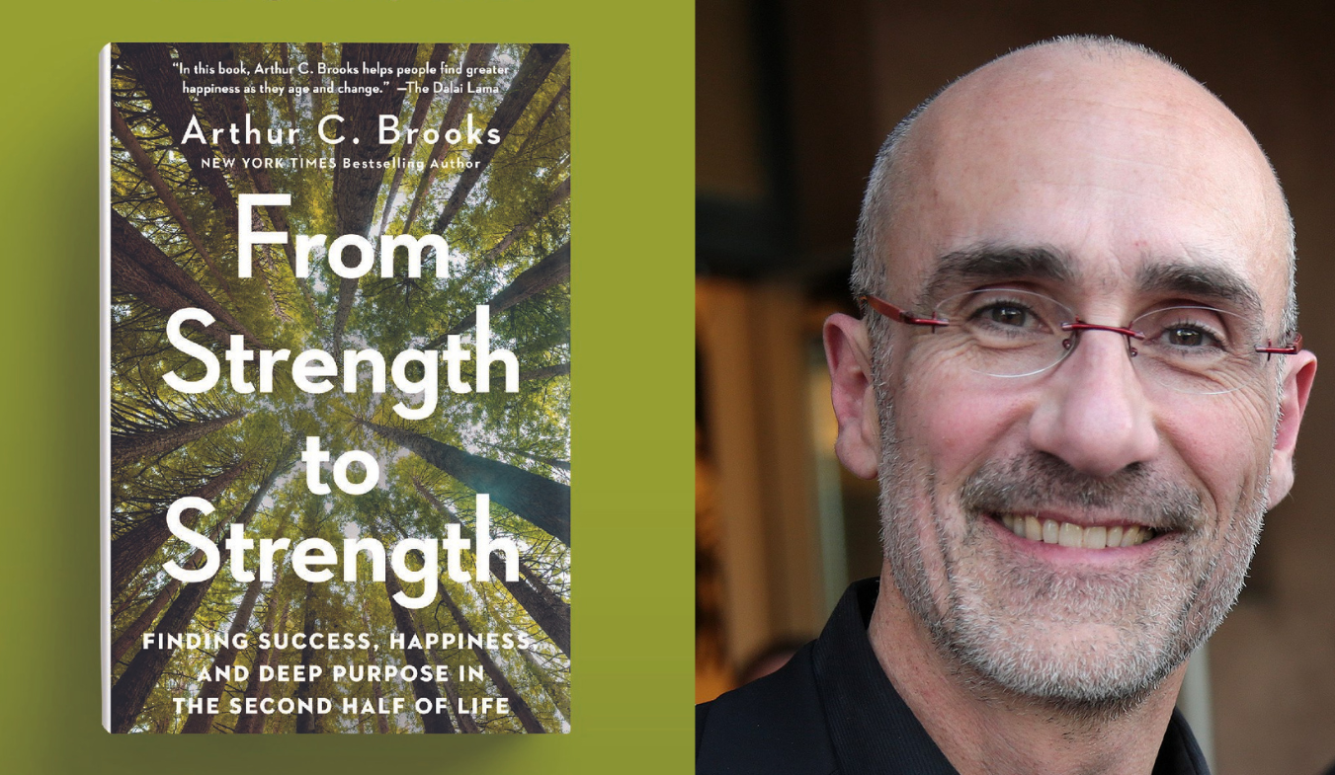

A review of Arthur C. Brooks’s new book, ‘From Strength to Strength.’

The man on the plane wished he were dead. Despite being a household name in America, the elder statesman feared being lost to the sands of time. He confessed to his wife that he felt unneeded and useless. The world had moved past him. His life—his entire being and sense of self-worth—were anchored in the past during a time when he meant something, when he got things done, and when people respected him. But as he left his seat, passengers began to murmur words of veneration. The airline staff recognized and thanked him.

Arthur Brooks was seated just behind the man watching all this, and the whole episode struck him as bizarre. In the introduction to his latest book, he recalls wondering: “Which more accurately describes the man—the one filled with joy and pride right now, or the one twenty minutes ago, telling his wife he might as well be dead?” That conversation stuck in Brooks’s craw for a decade, and finally provoked him to ask the same question of himself.

As a successful writer, bestselling author, and think-tank impresario, Brooks had life by the balls—money, notoriety, prestige. He’d mastered the hedonic treadmill better than most. But unlike the man on the plane, Brooks knew there was an impending expiry date. Cognizant that intelligence peaks for many in their 30s and 40s, he makes reference to the distinction drawn in the 1940s by British psychologist Raymond Cattell between smarts (fluid intelligence) and wisdom (crystallized intelligence).

Brooks has spent the last decade fixated on this dilemma, embarking “on a personal quest to turn my future from a matter of dread to an opportunity to progress.” From Strength to Strength is the upshot of a philosophical pilgrimage that sent Brooks across the globe in search of a cure for the “striver’s curse,” which afflicts those who have achieved success but who are eventually forced to step back from it. Some are even forced to do so because they’ve become too slow, old, and feeble to stay in the game.

It’s not just Harvard professors like Brooks that confront this crisis. Joe Rogan has spoken about the hole left in fighters’ hearts when they leave the limelight of the Octagon:

One of the things I think about sometimes with all the great fighters that I’ve seen come and go is just how difficult it must be for some of them to leave behind the incredible excitement and intensity of the world of being a professional fighter and then reset your life and find yourself something else to dedicate your time and interest to. … When it’s time to move past that and into a new phase of life I would think that for some it must be incredibly difficult.

It is, and so the book’s remaining nine chapters offer a roadmap towards a deeper and more durable sense of meaning. Building on his premise of inevitable professional decline, Brooks uses the contrasting examples of Johann Sebastian Bach and Charles Darwin to teach us about the art of aging gracefully. Bach holds a special place in Brooks’s heart. Brooks himself aspired to be the best French horn player of his generation, and even landed a prestigious gig with the City Orchestra of Barcelona at the age of 25.

However, unlike his idol, Brooks never achieved the stardom he sought. Not only did Bach publish a thousand compositions, but he also managed to father 20 children (yes, you read that right). One of his litter, Carl Philipp Emanuel (CPE), became the new generation’s greatest composer, ushering in his own father’s musical obsolescence. Bach could’ve moaned and fretted about this, but he didn’t.

Overshadowed by his own son, Bach couldn’t imagine that, today, he’d be the more famous composer. When Mozart said, “Bach is the father, we are the children,” he was reportedly referring to CPE. Thankfully, Bach didn’t hang up his harpsichord; instead, he found time to write The Art of Fugue, which was rediscovered a century after his death and is still performed in concert today.

The elder Bach died mid-sentence, writing music. He aged gracefully, enjoyed two loving marriages, and when he reached what Brooks calls the “Second Curve,” where one’s fluid intelligence recedes, he fell back on his crystallized intelligence. Rather than resenting his inability to stay with the times, Bach “reinvented himself as an instructor,” Brooks writes. “He died beloved, fulfilled, respected–if not as famous as he once had been–and, by all accounts, happy.”

Darwin, on the other hand, failed to manage the Second Curve. At 22, he joined the scientific expedition of a lifetime aboard The Beagle and spent the next five years traveling the globe collecting “exotic plant and animal samples.” Over the coming decades, Darwin contemplated how life adapts to diverse environments, and ultimately published his life’s work, On the Origin of Species, at the age of 50.

Most people would be satisfied with such an astonishing accomplishment. But Darwin was addicted to success and unable to live up to the high bar set by his own discovery. Still famous, Brooks writes, Darwin “was increasingly unhappy about his life, seeing his work as unsatisfying, unsatisfactory, and unoriginal.” Darwin said as much. “I have not the heart or strength at my age to begin any investigations lasting years, which is the only thing which I enjoy,” he confessed to a friend. “I have everything to make me happy and contented, but life has become very wearisome to me.”

To most readers, Darwin’s displeasure will seem incomprehensible. His work remains relevant today. He was buried in Westminster Abbey “a national hero,” yet his last years were filled with depressing thoughts of decline and uselessness. While Bach embraced his Second Curve, Darwin didn’t know it was there and crashed right off it. He thought, as Brooks once did, that we are our work and that our intellectual powers never wither or retreat.

Not only did Darwin fail to anticipate his impending professional decline but as Brooks goes on to show, he suffered from the strikingly modern frailty of workaholism. Whereas Bach could fall back on teaching and family, Darwin’s entire existence–his happiness, self-worth, and purpose–derived exclusively from his work. If he couldn’t work or stumble across any more groundbreaking ideas and if no one bothered to pay attention to him, Darwin concluded he was worthless. The term “workaholic” was coined in the 1960s after the psychologist Wayne Oates’s own son asked for an appointment to see him. Realizing that he’d buried himself in his work to the neglect of the world around him, Oates defined workaholism as “the compulsion or the uncontrollable need to work incessantly.”

Brooks traces the remarkable history of success addiction/workaholism. Winston Churchill had his “black dog” that hounded him throughout his life. “Unable to leave his tortured mind unattended during his crushing schedule as a wartime prime minister, he simultaneously wrote forty-three books,” Brooks writes (great, now those of us who haven’t written a single book feel lousy!). Lincoln battled his “melancholy.” Saint Augustine acknowledged his craving for the attention of others in his book Confessions. “I panted after honors … boiling with the feverishness of consuming thoughts,” he wrote over 1,600 years ago. Passing a street beggar in Milan, Augustine writes: “He was joyous, I anxious; he void of care, I full of fears.”

Brooks believes the drive to succeed stems from objectifying ourselves. While we are often taught not to objectify others or use them as means to our own selfish ends, “it starts to get more complicated when the objectifier and the one being objectified are the same person,” Brooks argues. “When we think ‘I am my job’” Brooks writes, “We become [Karl] Marx’s heartless work overlord to ourselves, cracking the whip mercilessly, seeing ourselves as nothing more than Homo economicus.”

Too much is never enough. Once you get on the hedonic treadmill and crank it up to 10, it becomes difficult to get off without being thrown. “Wealth is like sea-water; the more we drink, the thirstier we become, and the same is true of fame,” philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer once wrote. Because once you have stepped onto the first rung you’re not grateful to be on the ladder, you’re envious of those above you. That’s what afflicted the man on the plane. He’d ascended to the top, looked down upon his conquest, only to find himself pushed aside before he had finished enjoying the view.

Over the years, as Brooks tinkered with philosophy and books and experiences, he arrived at “a formula that encapsulates all the lessons I have learned and now strive to live: Use things. Love people. Worship the divine.” He needed to set something down, something digestible and easy, which would acknowledge the reality that sometimes “we must fight our natural instincts if we want to be happy.” He’s not telling us to “Turn on, tune in, drop out,” as Timothy Leary recommended. He just asks us to get the basic stuff right: family, friends, and love. Secure those, Brooks assures us, and you’ll be alright. If not, go ask for a refund.