Scotland

The Opposite of Junk

A dozen journals left to us by my wife’s Scottish grandmother were destined for the recycling bin—until we took a look at what was inside.

Long-term residency in the same cottage-sized house has left me with an awful lot of stuff that I don’t exactly use every day, but cannot quite bring myself to unload. Some people I know have performed household purges the moment their kids moved out and then, to make sure they couldn’t backslide, downsized their abodes. But my wife and I are, most decidedly, not constituted this way. We’ve never felt drawn to a Spartan existence and have little use for the ruthless philosophies of Marie Kondo. We sometimes will call ourselves amateur archivists. But the more accurate term would be packrats.

Kirtley and I knew this about one another before we wed. She’d shown me her immense assortment of fetchingly printed tissue-paper fruit-wrappers from around the world. And among the oddments crammed into the U-Haul that I brought into the marriage was every LP released as part of the Beatles-led British Invasion (all of their covers besmirched with the grandiose signature of Herm that I’d developed as a 12-year-old and couldn’t ever bring myself to retire). I retain nearly all of those albums to this day, even though I repurchased most of them in CD format and haven’t had a functioning turntable for 20 years.

And then there’s the books, which include, on my end, exactly 89 different titles by G.K. Chesterton alone. I did pare back my almost-as-extensive collection of J.B. Priestley titles about 30 years ago, and, almost instantly regretting it, built it back up to almost 60 again. My wife’s bibliophilic appetite came to rival my own. So now whenever she launches into one of her exhortations to clear out the shelves, I can simply reply, “You first.”

Sometimes, a purportedly well-meaning visitor to our empty nest of a home will gently suggest that our three children might not thank us if all this stuff is still here for them to sort out once we’ve shuffled off this mortal coil. It’s troubling and very much unwelcome advice—so much so that our frosty response might leave said guest with the (not incorrect) impression that, presented the choice of what to put to the curb, we’d sooner pick him than the archived treasures arrayed around us.

Moreover, given the uptick in home values of late, I’d say it might be well worth our (presumably grief-stricken) kids’ time to sort through a few bags and boxes before the For Sale sign gets banged into the front lawn. Oh and did I mention that a good number of those Chestertons are first editions—including a specimen that bears the author’s signature? One of the Priestleys, too, and a Walter de la Mare. None of these items will attract the attention of auctioneers at Sotheby’s or Christie’s, mind you. But taken all together, they might fetch a tidy sum.

One problem is that my consideration of even a single unused item can set me struggling existentially with that teeter-totter distinction between family heirloom and plain old junk. The latest iteration of this struggle began on Ash Wednesday, when Kirtley settled into her Lenten project for the year: resuscitating my paternal grandmother’s bedspread. It’s a gorgeous white cover comprised of elaborately crocheted four-inch squares and surrounded by fringe. My parents never used it, partly because it was white and a challenge to keep clean (unlike some more colourful throws and rugs that she’d also made for us), but also because the craftsmanship made it seem more like artwork than bed linen.

Back in the 1960s, my 15 year-old self wasn’t encumbered by such scruples. I pulled it out of the cedar chest where it had been carefully stored, and took it down to the basement of our Wortley Road home in London, Ontario. I was then setting up a psychedelic-dungeon-themed bedroom space to suit my newfound identity as moody and rebellious adolescent, and half expected that one or both parents would prevent me from co-opting this precious family object. But neither raised any objections. I employed it down there for about six years, and then through most of my residency in an East London bachelor pad, until Kirtley moved in and we graduated to a double bed that needed a wider spread. (As well as being finely crafted, the bedspread is extremely heavy. Some experts contend that a slightly pressing weight in one’s bedding encourages deeper sleep. I certainly slept like a rock back then, but that probably had more to do with my age.)

Gran’s bedspread endured a fair bit of abuse in the form of coffee and wine spills, as well as splattered candle wax. But the real engine of destruction was my first mongrel, Myrtle, who used one edge of it as a chew toy when she was teething. (Bad dog!) Most of Kirtley’s recent reparative attentions—following 40-some years of consignment to the bottom of another cedar chest—went to that most damaged edge, from which she removed two complete rows, and then used some of the more intact squares extracted from the removed material to replace disfigured sections in the interior. The operation was a success, and the bedspread rose anew like an only slightly shrunken phoenix.

At our big Easter dinner in April, we showed off the refurbished spread, which caused my brother Bob, our most reliable curator of family lore, to tell some stories about its creator, Edith Maude (née Morgan) Goodden (1888–1971)—stories I’d never fully taken in or adequately appreciated. Truth be told, she wasn’t the cuddliest of grans. She often lived in Ottawa with my dad’s sister’s family. And in those years when she was London-based, I mostly knew her as a regular Sunday dinner guest who was tuned in far more to our parents than to my older brothers and me (though she did always contribute a box of McCormick’s Peanut Brittle to our repast), as well as being an occasional and rather stern babysitter.

The most memorable Gran story that Bob related regarded our only sister, whom none of the four Goodden boys ever got to meet. Barbara Jane, our parents’ first child, was born in 1944 with spina bifida, and died six months later, without ever leaving St. Joseph’s Hospital. I’d always wondered how different all our lives would have been if she’d survived and flourished.

Our parents were shattered by the experience. Mother in particular went into a real tailspin of grief that was shot through with feelings of inadequacy and shame. Many days, she couldn’t get out of bed, let alone make her way to the hospital to confront a situation that everyone knew wasn’t going to get better. The story of her emotional paralysis was out of keeping with the brave woman I knew, who I felt would have done anything to keep me comforted and safe. It disturbed me, because it spoke to the depth of her misery. But by God, I cannot judge her for collapsing as she did.

And this is where that grandmother, the one I always found a little standoffish, stepped up to face what must be faced, offering up whatever love and consolation she could. Every day of Barbara Jane’s short life, Edith Maude was at her side, sitting sentry with her granddaughter in an antiseptic ward that was the only world that poor kid would ever know—and, I can’t help speculating, probably taking up her needles and crochet hooks from time to time, so as to wrest a little beauty and mercy where she could.

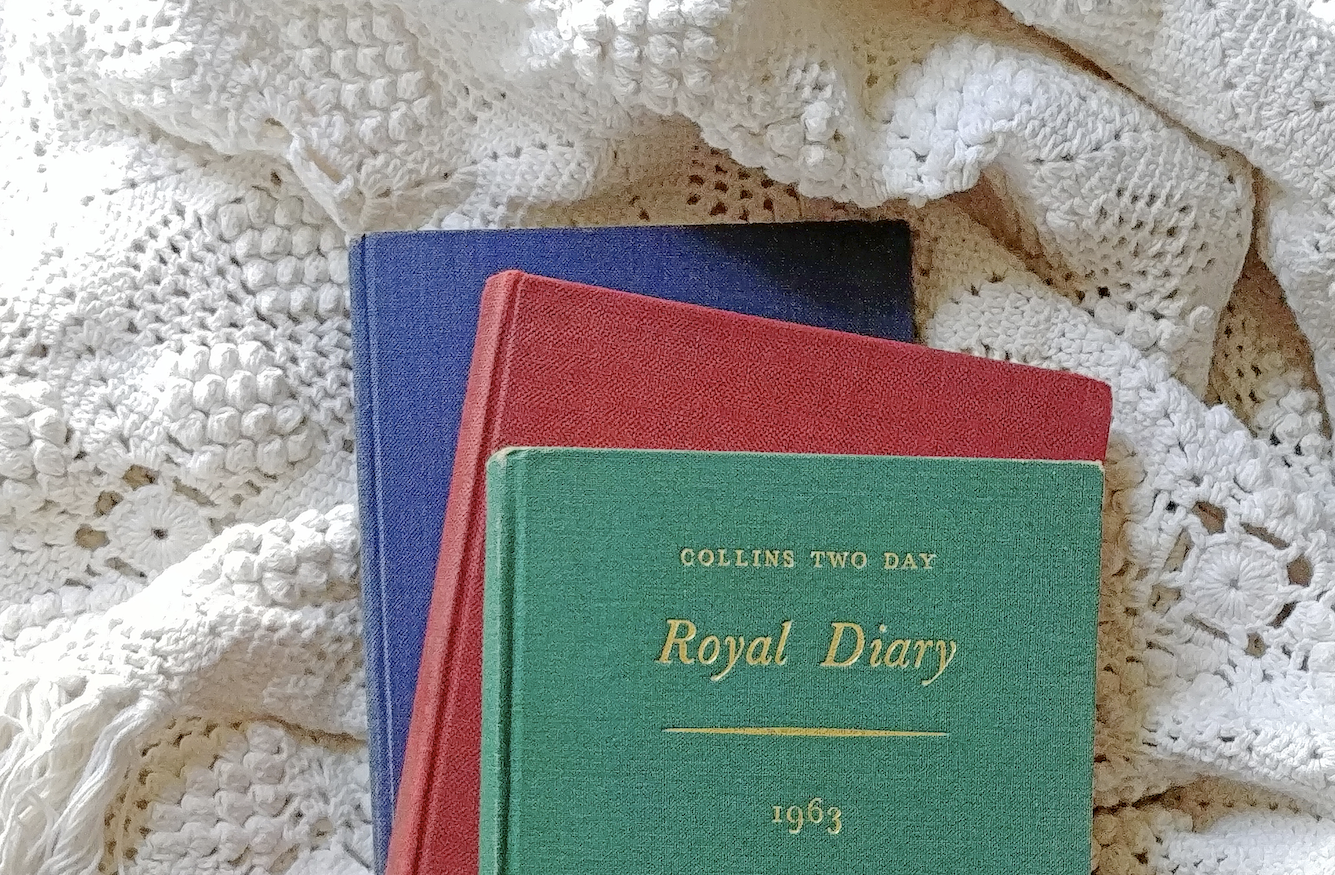

In May, Kirtley turned an eye toward the 12 volumes of diaries written by her own maternal grandmother, Margaret Davison Scott Bentley (née Hudspeth) Cranch (1887–1971). These came into our possession when Kirtley’s mom went into care at the local Dearness Home, where she died three years ago this spring. Kirtley had inspected these volumes only in parts; flipping from page to page and noting that her grandmother always seemed to be writing about the weather. Mind you, the weather could be interesting enough in the Scottish village of Gartocharn, where the air got churned up as it moved between the frequently snow-capped Duncryne Hill and the open water of Loch Lomond. But did the world really need 4,383 pages worth of meteorological variations from 1958 to 1970?

Coveting the space taken up by these not-particularly-scintillating books, Kirtley planned to take a picture of the whole stack, digitally scan a few representative pages, and then put them out of their misery, as it were. But before taking any step so final as that, she knew she’d have to dig into these volumes more closely, just to make sure her initial appraisal had been correct.

As quickly became obvious, it wasn’t. We’ve been passing the books back and forth for weeks now, pointing out entries of particular interest and re-reading our favourite bits. We’re mesmerized by these glimpses of mid-20th-century life (which often feel like they could’ve been drawn from the century before) in the out-of-the-way village where Margaret and her sister Mary (Mamie) Kirtley Hudspeth—a retired matron from the Henry Brock Memorial Hospital in Glasgow who never married—lived out the majority of their final two decades together. (Mamie herself produced a few journals that fell into our possession. These are mostly filled with notes relating to her hospital work, some really fine sketches in pencil and pen, and lots of quotes, often of a religious nature, from great poets and writers.)

Yes, the very first paragraph on every page of Margaret’s journals faithfully recorded that day’s weather, whether gratefully or ruefully. But the weather was important to Margaret Cranch because it influenced—and sometimes determined—what she could accomplish by way of chores, social visits, and church prayer. Mamie, younger by five years (and who survived her sister by the same five-year span), comes off as the sturdier of the pair, less inclined to suffer banger-clanger headaches and more able to stick to schedule. A blizzard had to be pretty apocalyptic to keep Mamie from making it out to early service at the church, though when she did get back, in all likelihood Margaret would have made their breakfast. It wasn’t uncommon for Margaret to go to bed as early as 6.30pm and to wake up in the wee hours of the morning when she wrote her diary entries and a formidable number of letters to her scattered family.

There’s one quirk of Margaret’s that I do find a little trying. If she’d watched a television show or a movie, she’d almost always write down the title and sometimes a brief description. But this never happened with books. Even though she’d always have one on the go and express her pleasure that a pile had materialized over Christmas and at birthdays, I have yet to come across any kind of description.

So-called world events rarely intruded on Margaret’s journal entries. The assassination of JFK really shocked her, coming just a few months after her half-year visit to Canada in 1963 (which gave her a vivid appreciation of how life was lived in the “New World”). And the funeral of Winston Churchill in 1965 evoked a lot of reflection on the two World Wars. In the first war, her husband almost died while sustaining the injuries from gassing that would carry him off by 1934. In the second one, Kirtley’s mom Sheila (Margaret’s daughter) served as a nurse in India, and met the Canadian serviceman she would marry five weeks later, with whom she would go start a life on the other side of the globe.

But in most years, none of these world-shaking events occupied more diary space than was devoted to the week-long campaigns of spring cleaning in which, room by room, she and Mamie turned out, washed, and reassembled the entire cottage. We also follow, installment by installment, the sisters’ progress in knitting sweaters and stockings and shawls for all the loved ones in their lives. The dimensions of these sometimes elaborate creations had to be updated each year as Margaret’s grandchildren grew; and then, hoping they’d got everything just right, all that knitwear would be packed into the enormous Christmas parcels—along with sweets and calendars and more (unidentified) books—that were sent out to different chapters of their family.

Part of Kirtley’s fascination with these diaries relates to the many qualities and attributes that were evidently passed on from her gran to her mom. And in certain surviving photographs, their physical resemblance seems uncanny. In one entry, penned just before turning in way too early after a particularly trying day, Margaret described herself as “utterly utterly,” which set Kirtley off in laughing remembrance of her mom’s use of those words. Recovering from a cold, both ladies would pronounce themselves as “bettering.” And if you’d just set out some flowers or smoothed out the curtains, you were “garnishing” the room.

In 1970, when Kirtley, her mom, and her sister all stayed in Gartocharn for a month, Margaret wrote entries in the final days describing how she was bracing herself to get through the sadness of their imminent parting. She had extended herself so unstintingly in hosting them that she actually fainted from over-exertion a few days after they’d left. And a few days after that, she spent an entire afternoon sitting outside and recharging her batteries by “watching the clouds & the shaking of the trees—very soothing and peaceful.” This reminded me so much of a day at Port Bruce Beach, when Kirtley and I left Sheila sitting in a lawn chair just out of the sun to head down to the pier, and returned several hours later to see her in exactly the same posture in that chair (still breathing, we were relieved to observe).

That 1970 volume is my favourite of the diaries, as Kirtley’s grandmother provided so many vivid sightings of the girl I would meet for the first time only a month later in film class. “Kirtley is a darling,” Margaret wrote, “tall and very slim,” “with masses of long hair,” and “sitting with her sister on the lawn,” both of them “wearing the beautiful dresses they had bought” at Laura Ashley’s first shop on Pelham Street, in South Kensington.

That is some first class reporting there, Margaret Davison Scott Bentley (née Hudspeth) Cranch. You can be sure that Chesterton, Priestley, and De la Mare will find the curb before you ever do. All of your (very) limited edition books are safe with us.