Politics

Progressivism, Sexuality, and Mental Illness

Is contemporary liberal-left culture producing greater mental distress?

Will America be entirely gay in a few generations? Will everyone be mentally ill? It would appear so from a straight-line extrapolation of the stunning rise in both LGBT identification and mental illness among young Americans.

Let’s begin with trends in sexual orientation among young people. A recent Gallup survey found that: “Roughly 21% of Generation Z Americans who have reached adulthood—those born between 1997 and 2003—identify as LGBT. That is nearly double the proportion of millennials who do so, while the gap widens even further when compared with older generations.” Abigail Shrier, meanwhile, reports a 1,000-fold increase in trans identification. Reactions to these trends have varied. Republican Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene thinks they indicate that there will be no straight people in a few generations; Bill Maher lampoons the increase as a rebellious fad; and progressives celebrate the rise as an electoral boon for the Democrats. Other liberals view the rise as the product of increasing toleration, similar to left-handedness, in which identification increases as stigmas are lifted and people come out of the closet.

Of these responses, Maher’s is closest to the target. A granular look at survey data on same-sex behaviour and LGBT identity shows that identification is increasingly diverging from behaviour. More importantly, those who adopt an LGBT identity but display conventionally heterosexual behaviour are a growing and distinct group, who lean strongly to the left politically and experience considerably greater mental health problems than the rest of the population.

By contrast, those who engage in same-sex behaviour are more politically moderate and psychologically stable. These facts sit awkwardly with the progressive view that the rise in LGBT identity, like left-handedness, is explained by people increasingly feeling that they can come out of the closet because society is more liberal. My analysis of these data raise another interesting question: Has some of the increase in anxiety and depression among young people, like the LGBT identity surge, arisen from a culture that values divergence and boundary-transgression over conformity to traditional norms and roles?

Is the LGBT surge real?

In the New York Times, conservative columnist Ross Douthat has argued that the apparent LGBT surge is entangled in a new “LGBTQ Culture War.” This fraught dispute has already produced a burst of legislative activity in red states, including “bathroom bills” limiting access to toilets by biological sex, and education initiatives such as Florida’s so-called “Don’t Say Gay” bill. Douthat believes that unease about the dramatic rise of LGBT identification lies at the heart of the new politics of sexuality.

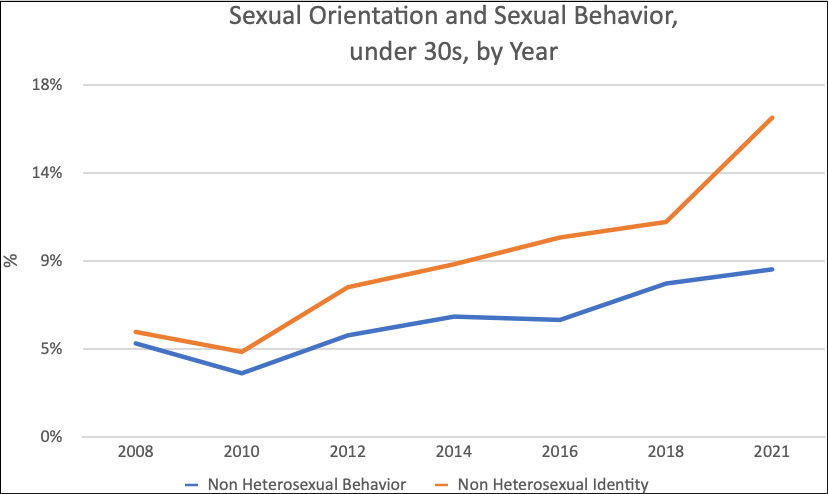

But has the LGBT share of young people really tripled in a decade? It has not. First, a growing share of LGBT identifiers engage in purely heterosexual behaviour. Figure 1, drawn from the General Social Survey (GSS), shows that, in 2008, about five percent of Americans under the age of 30 identified as LGBT and a similar number had a same-sex partnership in that year. By 2021, the proportion identifying as LGBT had increased 11 points to 16.3 percent but the share reporting same-sex relations had only risen four points, to 8.6 percent. LGBT identity had become twice as prevalent as LGBT behaviour. We must also bear in mind that 20 percent of young people now report no sex in the previous year, which means the four-point rise in same-sex partnering since 2008 is actually closer to a three-point rise: not nothing, but hardly a sexual revolution.

The trend towards greater LGBT identification has been particularly pronounced for young women, among whom there are three bisexuals for every lesbian in the 2018–21 period. Among young men, on the other hand, gays outnumber bisexuals and the LGBT total is only half as large as it is for women. Other large major surveys conducted by the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) and by Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES) find a similar pattern.

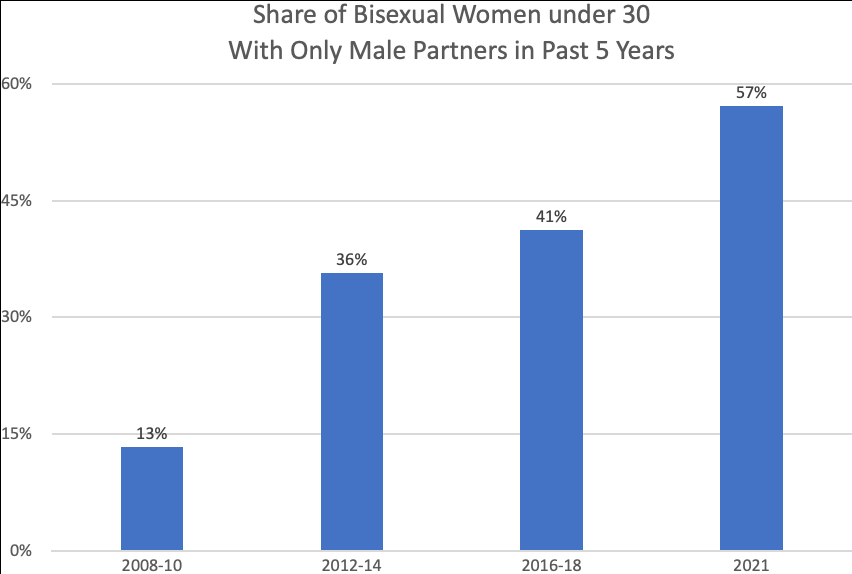

Furthermore, the GSS data show that bisexual women are the fastest-growing category, accounting for a disproportionate share of the post-2010 rise. A closer look at trends among female bisexuals in figure 2 shows that an increasing share of them display conventional sexual behaviour. In 2008–10, just 13 percent of female bisexuals said they only had male partners during the past five years. By 2018 this was up to 53 percent, rising to 57 percent in 2021. Most young female bisexuals today are arguably LGBT in name only.

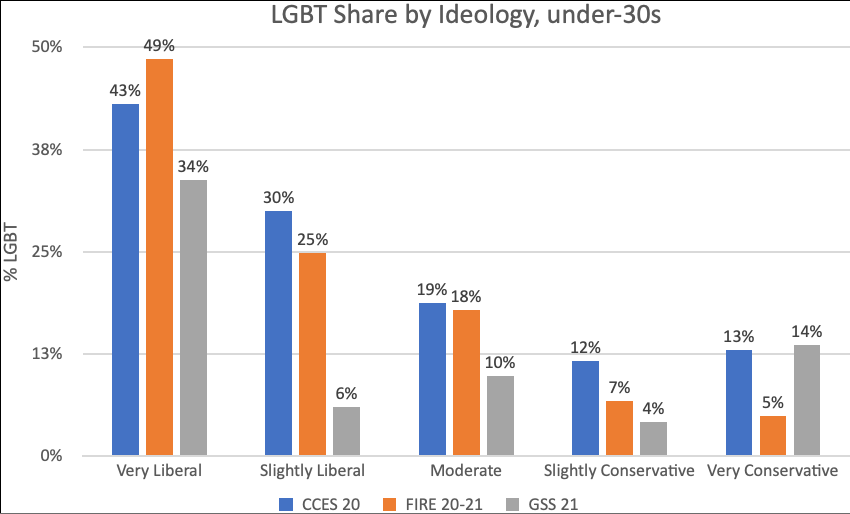

Second, the rise is less dramatic than it appears to be because LGBT identifiers are heavily drawn from the cohort who identify as “very liberal” on a five-point ideology scale (“very liberal” to “very conservative”). In the GSS, the LGBT share rose from 11 to 34 percent between 2008 and 2021 among very liberal young people but increased from only three to nine percent among the slightly liberal, moderate, or conservative who make up around four-fifths of the total. Figure 3 shows the general pattern across the FIRE, CCES, and GSS in 2020–21.

Some of the surveys show a major difference in the rate of LGBT identification between very liberal and slightly liberal respondents, with less difference between moderates and conservatives. The distinctive profile of the very liberal on LGBT identity differs from, say, support for gay marriage, where there is a relatively linear pattern as we move from left to right.

Trends among elite students in the FIRE surveys show a pronounced tilt whereby left-leaning students are especially likely to reject the heterosexual label. Among very liberal white female students in leading universities, those who strongly approve of shouting down offensive speakers have a seven in 10 chance of identifying as LGBT compared to four in 10 for very liberal female students who strongly disapprove of shout-downs. A similar divide holds for views of the police among white liberal students.

Minority liberal students are much less likely to identify as LGBT, and political views matter much less for them in predicting LGBT identity. But among young people without a college degree, minorities are as likely as whites to identify as not heterosexual. In other words, it appears that a transgressive culture which values difference also encompasses less political people.

Has the LGBT identity spike made young people more liberal? No. The overall ideological and partisan balance among the under-30s has been relatively stable since 2008. If being LGBT causes someone to become liberal, rather than the reverse, we should have seen a big shift to the left among young people. Yet this has not occurred in the United States. Instead, it appears that the rise in LGBT identification has been siloed among the very liberal, limiting its wider political impact.

Third, while the jump in transgender identification is real, there is now evidence that the trend has peaked and begun to decline. The FIRE data show that the weighted proportion of undergraduates identifying as trans declined significantly among a set of 50 top schools, from 1.5 percent in 2020 to 0.85 percent in 2021. In 2021, older students were significantly more likely to be trans than younger (18–19 year-old) students. Canada’s 2021 census data similarly show that the proportion of transgender and non-binary individuals rises in every age group as we move from old to young, but peaks at 0.85 percent among the 20–24s, declining to 0.73 percent among the 15–19s. Likewise, British data shows that referrals for potential gender reassignment surgery jumped from 136 in 2010–11 to a peak of around 2,750 in the years 2018–19 and 2019–20 before dropping to 2,383 in 2020–21, the latest year for which we have data. It seems we have passed peak trans.

Finally, all reputable survey firms struggle to get a representative sample of mobile and highly distracted young people to complete surveys. Those who are not at university are especially hard to reach. As a result, psychological traits such as openness to experience, neuroticism, and agreeableness, as well being very online, which have varying levels of association with LGBT identification, predict a higher likelihood of filling out a survey. This skews surveys.

For instance, in Britain, over a quarter of the 5,407 18–20 year-olds on YouGov’s 2022 panel identified as other than heterosexual compared to only 7.6 percent of 2019 official Office of National Statistics (ONS) figures for 16–24 year-olds. The latter uses a similar question, but is based on a 320,000 national sample, using census sampling frames. Canada’s census, meanwhile, reports 0.8 percent transgender and non-binary among Gen-Z in 2021 compared to Gallup’s 2.1 percent estimate for the United States in the same year. These comparisons suggest the share of sexual minorities in surveys should be deflated by at least half.

The LGBT rise in the context of the youth mental health crisis

So, the surge in LGBT identification is less dramatic and less consequential than it appears to be at first glance. And this is before we take into account the likelihood that many of these young people may drift in the direction of conventional sexual identities as they age and settle down.

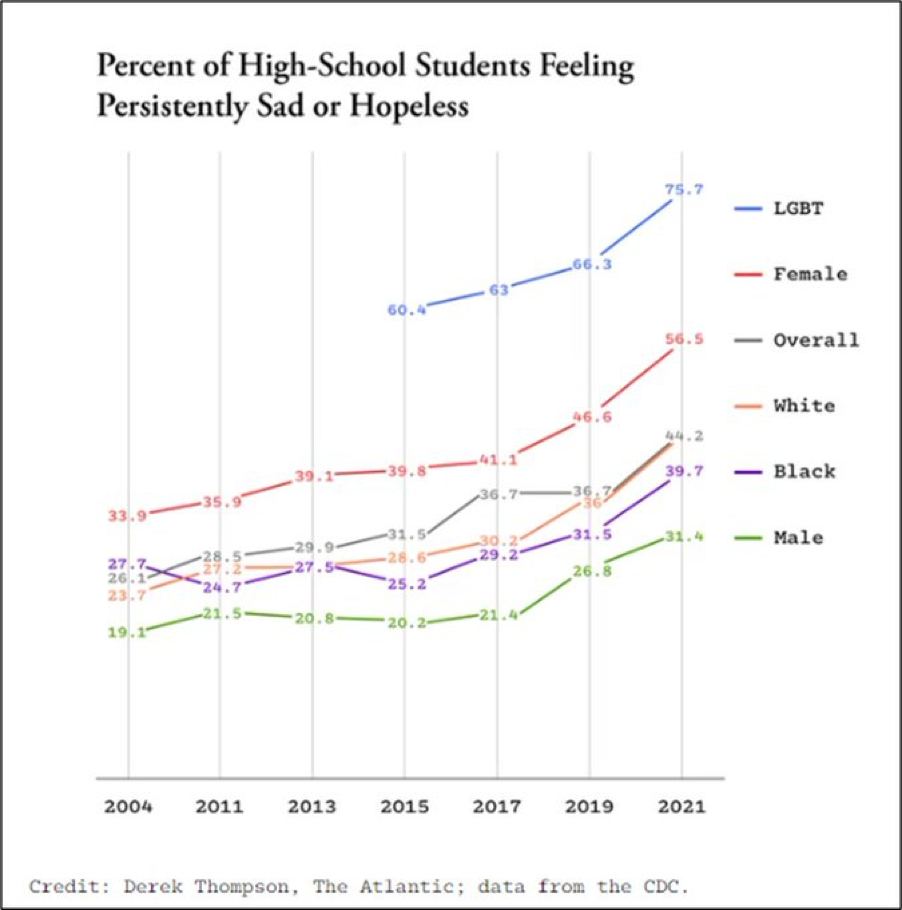

There is, however, a more serious issue thrown up by these trends—rising levels of anxiety and depression, especially among LGBT, female, and liberal young people. Derek Thompson’s Atlantic article (the findings of which are reproduced in figure 4), shows that over three in four LGBT-identifying teens in 2021 said they felt persistently sad or hopeless, as did 57 percent of female teens. The 2021 GSS and a 2020 Qualtrics survey I conducted show that very liberal young people are twice as likely as slight liberals, moderates, and conservatives to say they have experienced depression and anxiety while LGBT young people are 2.5 times more likely to report these symptoms.

This means there is a strong correlation between people’s responses to three questions: sexual orientation, mental health, and political beliefs. In fact, a common factor accounts for almost half of the variation in the answers across all three questions, suggesting that they heavily overlap.

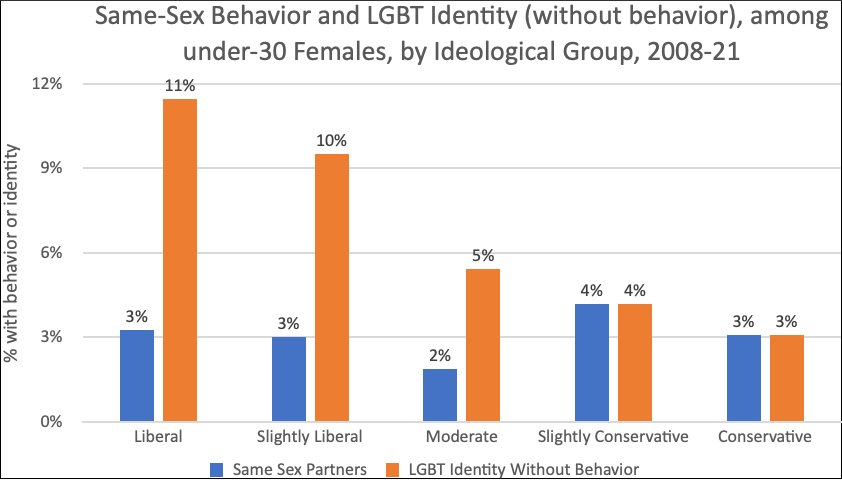

While it can be difficult to pick causation and correlation apart, the pattern in figure 5 reveals something interesting. The figure compares two separate groups: young women who report having slept with a woman over the past year, and young women who did not sleep with a woman but identify as LGBT.

The graph shows that the share of women who have had a same-sex partner doesn’t differ a great deal in their ideology: around three percent of both liberal and conservative women reported a same-sex experience during 2008–21. Where there is a big ideological difference is among women who have not had a same-sex partner but still identify as LGBT. Of the most liberal young women, 11.5 percent fall into the LGBT identity-without-behaviour category, but just 3.1 percent of conservative young women do. The sample size is not large, but the pattern is consistent: LGBT identity, not behaviour, is what predicts being very liberal for women.

Interestingly, for men, this pattern does not hold. Though the sample is small, the male trend shows that LGBT identification and behaviour remain closely linked and both are related to liberalism, suggesting a better fit with the conventional view that being a noticeable minority inclines people to lean left. Yet among young women, the fastest growing group, those with LGBT identity-without-behaviour stand out as distinctively left-wing.

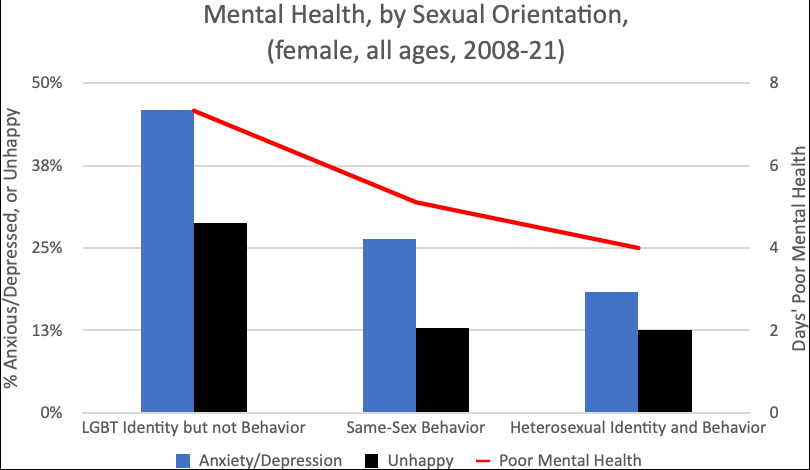

Turning to mental health, I find the same pattern—women exhibiting same-sex behaviour are far less different from the average than women who have conventional sexual behaviour but identify as LGBT. Expanding the data to include women of all ages so as to maximize sample size, the pattern in figure 6 is clear: women who engage in same-sex behaviour differ very little from the general female population on three mental health indicators.

However, women who identify-without-behaving LGBT score significantly higher on anxiety/depression, unhappiness, and number of days of poor mental health during the past month. If intolerance is the reason for poor LGBT mental health, it is difficult to understand how those who are not same-sex partnered, and thus less likely to present as LGBT, should report worse emotional problems than those who are same-sex partnered. Here it is worth adding that women who had no sex partners did not suffer worse mental health than those who did, so the effect has nothing to do with people not having sex.

The progressive account—that LGBT identification is like left-handedness, that persecution explains mental illness, and that rising toleration leads to more people coming out—cannot account for the patterns in my data. A more parsimonious explanation is that left-liberal culture, especially among young people, inclines people to identify as both LGBT and as having a mental health problem.

This could stem from a partly heritable psychological disposition of high openness and neuroticism with low conscientiousness, as some research suggests. Another possibility is that a culture which celebrates divergence and transgression may be nudging those with intermittent same-sex attraction to label themselves LGBT, or inclining people with occasional melancholy to say they are depressed.

More seriously, it may be that modern culture is, as Boston University’s Liah Greenfeld suggests, anomic. That is, by breaking down established identity roles, narratives, and boundaries, it introduces dissonance, indeterminacy, and choice, increasing the rates of identity crisis and, by extension, psychological distress. The rise in mental health problems, she argues, is worse in the West than elsewhere in the world, reflecting the cultural specificity of mental illness. Her analysis takes a Durkheimian approach, which focuses on how a loss of communal regulation of desires and identities can produce higher suicide levels as the mind becomes unmoored from social givens in the external world.

In a recent article for the Wall Street Journal, Greenfeld adds that:

The more a society is dedicated to the value of equality and the more choices it offers for individual self-determination, the higher its rates of functional mental illness. … Equality inevitably makes self-definition a matter of one’s own choice, and the formation of personal identity—necessary for mental health—becomes a personal responsibility, a burden some people can’t shoulder.

Greenfeld focuses on how modern nations levelled hierarchies and certainties based on class and religion, producing more “madness” as people struggled to define themselves. But the same could hold for left-modernist culture, and its deconstruction of gender, as well as other traditional identities such as nationhood itself. Those in highly left-liberal circles may come to view gender as a matter of fluidity and choice rather than ascription. This loss of boundaries may lead to dissonance between a person’s interior mental state and the outside world, and between prior self-understandings and radically deconstructed versions of these understandings, producing anomie.

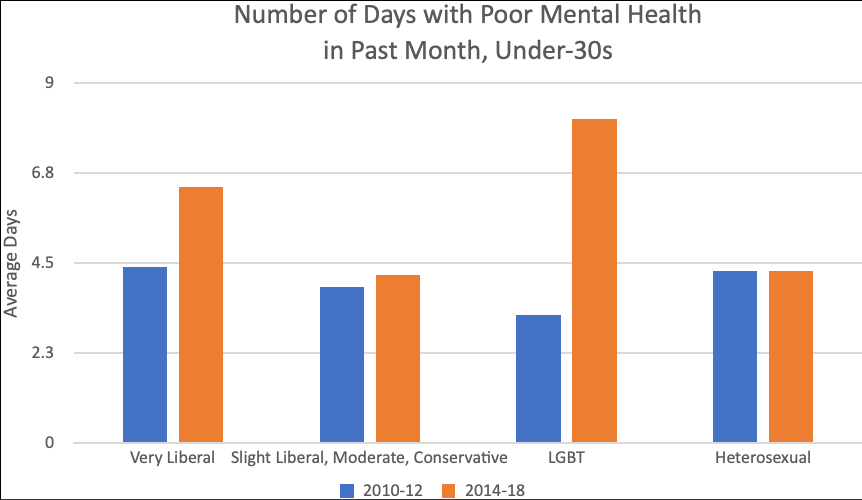

The data indicate that the link between LGBT identification and mental health problems has grown closer over the past decade. A large, long-running study of American high-school students showed that mental health declined substantially faster among LGBT teens compared to heterosexual teens between 2012 and 2018. Figure 7 shows that among those under 30 in the GSS, a similar pattern emerges, with very liberal and LGBT individuals experiencing a sharper rise in unhappiness than others between 2010–12 and 2014–18.

So, between 2002 and 2012, seven percent of unhappy people under 30 were LGBT. However, by 2018–21, 22 percent of unhappy young people were LGBT—all during a period of rising toleration for sexual minorities. The well-known high incidence of mental illness among transgender youth is merely the most visible tip of a wider problem.

If the change over time is, like LGBT identification, largely a reporting difference, that’s one thing. But what if the data reflect a left-liberal culture that is producing greater mental distress? Or one which nudges people—especially the young—to identify as mentally ill, which focuses them on their emotional problems, leading to a negative psychological spiral? At the very least, one might have thought that researchers would have spent some time trying to test for anomic mental illness and its connection to left-modernist culture.

Yet, as Greenfeld notes, such research is essentially nonexistent. In addition to disciplinary constraints, this kind of endeavour is deeply unfashionable because it questions the taken-for-granted progressive narrative of discrimination, minority trauma, the fight for social justice, and the need for more resources for the psychotherapy industry. In the meantime, practitioners seem powerless to stem the tide of mental illness that now afflicts nearly half of young people and has been stubbornly rising across Western societies.