Liberalism and its Discontents—A Review

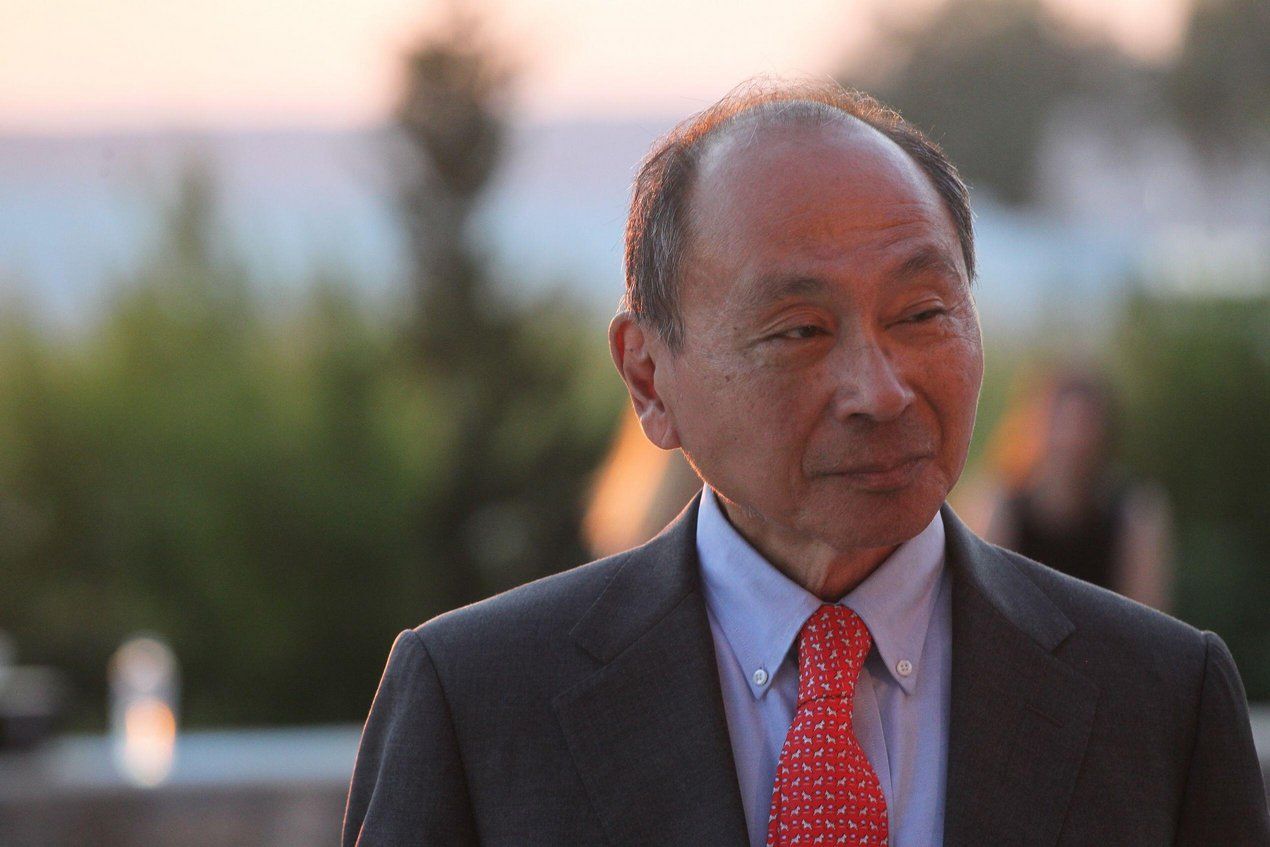

A Review of Liberalism and Its Discontents by Francis Fukuyama. Profile Books, 178 pages (March 2022)

Liberalism is in bad odour. In the third decade of the 21st century, it is an ideology with few friends. Derided with equal vigour by populists on the Right and “progressives” on the Left, it is no exaggeration to claim, as Francis Fukuyama does in his new book, Liberalism and its Discontents, that “liberalism is under severe threat around the world today.”

And yet, it was only just over 30 years ago that the same author—whose name is almost synonymous with liberal ideology—was proclaiming history’s “end.” Adopting Hegel’s historical teleology Fukuyama famously argued in 1992 that the fall of the Soviet Union marked the ultimate “end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalisation of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.”

So, history, it turns out, did not actually end, but what’s wrong with liberalism? Is it broken? Can it be fixed? Or was it a mistake, in the first instance, to prophesy that liberalism was history’s “absolute moment”? Like 1848, did history reach its turning point and fail to turn because it had some other telos—socialist, fascist, nationalist, religious?

Never an uncritical supporter of liberalism—always aware of the cultural and psychological toll its victory necessarily exacts—Fukuyama has long conceded that there “are many legitimate criticisms to be made of liberal societies.” Nonetheless, echoing Winston Churchill on democracy, Fukuyama insists still that “liberalism is the worst form of government, except for all the others.”

In Liberalism and its Discontents, Fukuyama argues that the wrong kind of liberalism is what’s wrong with liberalism. Neoliberalism, namely, is what’s wrong with liberalism—that, and the idea of the “sovereign self” advanced in John Rawls’s left-leaning iteration of the political philosophy. Exchanging contingency for teleology, this is a Hegel-free Fukuyama, newly aware that “eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.”

Liberalism and its Discontents is a sterling book. Fukuyama provides there a rousing defence of “classical,” or “humane,” liberalism. It is a call for liberalism to moderate itself if it wishes to survive from someone, notably, firmly embedded within the liberal tradition.

Liberalism, on Fukuyama’s account, is a pessimistic politics. What we get in his new offering is, effectively, a species of the liberalism of fear. Classical liberalism, Fukuyama explains, can be understood “as an institutional solution to the problem of governing over diversity.” Classical liberalism is not without aspiration, however. Tolerance may be its most fundamental principle, but it is also individualist, egalitarian, universalist, and meliorist. Which is to say, while classical liberalism is realistic about the human propensity for discord and violence, it is idealistic about the need for political equality and our potential for collective improvement. Candid to a fault, Fukuyama distinguishes between liberalism and democracy. The heyday, he claims, of what came to be known as “liberal democracy,” classical liberalism’s apotheosis, was the period from 1950 to the 1970s. After that, liberalism began to unravel. Liberalism became self-destructive and even illiberal when its core principles were pushed to extremes.

Fukuyama’s critique of neoliberalism is powerful and well executed. However, there is nothing new there. The Reagan–Thatcher revolution addressed, and solved, real problems. Yet, Fukuyama points to its unintended, and intended but adverse, consequences. Free trade leads to the expansion of markets and efficiency. It also leads to job losses for skilled workers in rich countries. Immigration, similarly, improves aggregate welfare. But, unsurprisingly, “few voters think in terms of aggregate wealth.” “A valid insight into the superior efficiency of markets evolved into something of a religion,” he notes, where natural monopolies were privatised, markets recommended for states without functioning legal systems, and deregulation applied to the financial sector. Neoliberalism, consequently, was hoiste by its own petard.

It is not just a question of misapplication, however. Neoliberalism, according to Fukuyama, is congenitally flawed.

First, channelling Henry George, Fukuyama questions if a singular focus on property rights is just. “What if that property was acquired by violence or theft,” he asks rhetorically. Second, Fukuyama argues that neoliberalism’s emphasis on “consumer welfare as the ultimate measure of economic well-being” betrays an ideology with its values out of kilter. Invoking Justice Louis Brandeis’s political interpretation of the Sherman Act, Fukuyama posits that social goods like neighbourhoods and ways of living ought to trump economic efficiency. Third, neoliberalism’s foundational assumption that human beings are “rational utility maximisers” is profoundly incomplete, he states. We do, indeed, often act as selfish individuals, but individualism is a modern phenomenon, not a historical constant, and people are perpetually making choices “between material self-interest and intangible goods like respect, pride, principle, and solidarity.” We are, in short, social and emotional as well as selfish and rational creatures.

Who knew? Well, if this all seems obvious to liberalism’s longstanding critics—conservative, socialist, social democrat—Fukuyama’s critique of left liberalism is genuinely novel. Fukuyama proceeds to eviscerate the form of identity politics that emerged initially as “an effort to fulfil the promise of liberalism” but descended instead into a state of psychosis, plagued by patricidal imaginings. It is here that the book excels.

In Fukuyama’s synoptic intellectual history, Rawls is a bridge to nihilism and wokeism. Unlike Lockean–Jeffersonian liberalism, which “enjoined tolerance for different conceptions of the good,” Rawls enjoined “non-judgementalism regarding other people’s life choices.” Placing justice prior to the good, swapping a theory of human nature for an abstract “original position,” autonomy was absolutised. Choice was elevated to first place among human goods, with devastating consequences. Character formation was neglected, and life, unbound from tradition and inherited social roles, was emptied of meaning. Fukuyama doesn’t use the phrase, but he might as well have: Rawlsian liberalism created a culture of narcissism. “Freedom to choose,” he complains, extends now not “just to the freedom to act within established moral frameworks, but to choose the framework itself.” In other words, anything goes. Indeed, the more non-conforming, the better.

When told that the individual is sovereign and that our task in life is to “self-actualise,” modern liberal subjects are predictably self-indulgent. They often behave like “the spoiled child of human history” described by José Ortega y Gasset, incapable of wonder and respect. Failing to observe the principle of charity, contemporary critical theorists, for example, habitually mischaracterise their opponents’ arguments, erecting caricatures which are duly demolished with ease. Distinguishing between a good kind of identity politics and a deranged kind, Fukuyama answers point for point the objections levelled at liberalism by the latter.

Acknowledging that liberalism has been illiberal, endorsing racist and patriarchal ideas and policies, he notes that these are not intrinsic to liberalism. Rather, they are “historically contingent phenomena.” Liberalism, moreover, as a universalist philosophy, provided—and provides—“the theoretical justification for its own self-correction.” Thus, Fukuyama rightly observes that “it was the liberal idea that ‘all men are created equal’ that allowed Abraham Lincoln to argue against the morality of slavery before the Civil War.” The goal of the sane version of identity politics, he goes on accordingly, is to “win acceptance and equal treatment” for members of marginalised groups “as individuals, under the liberal presumption of a shared underlying humanity.” This, however, is lambasted by woke ideologues as a mere assertion of power, an attempt—cynical or otherwise—to impose a liberal worldview on groups who do not wish to adopt one.

If Rawls gave us moral relativism, the “epistemic or cognitive relativism” which has become pervasive in recent years was authored, above all, by Michel Foucault. Facts are out. Subjectivity is in. Consistently fair, Fukuyama readily concedes that there is often a kernel of truth in what Foucault and his deconstructionist and structuralist forebears had to say. Ideas are not neutral. Scientifically “validated conclusions have indeed reflected the interests and power of those expressing them,” he concedes. For the most part, however, Foucault was a paranoiac. Allergic to authority, he identified power everywhere, in institutions and “the language used to regulate and talk about social life.”

The current extreme sensitivity to the mere expression of words, combined with an irrationally anxious suspicion that institutions are shot through with racism, sexism, and other forms of domination, is Foucault’s legacy. He gave us a political lens at once fragile and self-lacerating or aggressively assertive. Turning Foucault’s own argument against him, crucially, Fukuyama asks if “there are no truly universal values other than power, why should one want to accept the empowerment of any marginalised group?” Anarcho-tyrannical on the one side and ethno-nationalist on the other, both equally incapable of accepting diversity, the alternatives to liberalism do not bear thinking about. Fukuyama, however, can bear more reality than most.

The End of History was both melancholic (never-ending liberalism meant never-ending boredom) and, undoubtedly, hubristic. The Fukuyama that emerges from Liberalism and its Discontents is, in essence, a social democrat—a proponent, even—of a weak left post-liberalism. To some extent, he plays down the totalitarian threat posed by the woke Left. He is fully cognisant, though, of the danger posed by the populist Right. To avert catastrophe—a revival of violence, war, and dictatorship which characterised the first half of the 20th century—Fukuyama argues that classical liberals need to recognise the need for government. The real issue is not its size and scope but its quality. The Scandinavian countries, for instance, provide a good example of successful welfarist liberal societies. As a priority, wealth must be distributed more equitably the world over.

Most liberal societies at present, Fukuyama avers, tolerate far too much inequality. Not only that, but they are also vulgar, extravagantly consumerist, excessively permissive, too diverse, not diverse enough, and dominated by manipulative and unresponsive elites. Engaging with the work of American right post-liberals such as Sohrab Ahmari, Adrian Vermeule, and Patrick Deneen (somewhat cursorily, it must be said), Fukuyama happily accepts that the “substantive conservative critique of liberalism—that liberal societies provide no common moral horizon around which community can be built—is true enough.” However, he does not believe there is any practical way back to a thicker, perhaps religious, moral order. Moral relativism is “a feature and not a bug of liberalism.” To accommodate diversity, a sense of community must almost inevitably be thin. Still, the “spiritual vacuum” at the centre of liberal orders is regrettable.

According to Fukuyama, the best we can hope for is a liberalism aware of its flaws, a liberalism that “prioritizes public-spiritedness, tolerance, open-mindedness, and active engagement in public affairs,” is unembarrassed by national identity and cultural tradition, seeks to devolve power to the lowest feasible levels of government, and accepts human limits and promotes the virtue of moderation. A liberalism, in short, which seeks to compensate for its own ineradicable shortcomings. In so saying, Fukuyama sounds a lot like a reticent Red Tory or Blue Labourite—a critic of liberalism who is not anti-liberal—an impression created throughout his new book. Now, that is “progress.” What Fukuyama succeeds in showing us is that liberalism need not be commensurate with the extremes of individualism or wokeism. His version of liberalism repudiates both.