Feminism

Female Empowerment Shouldn’t Mean We Have to Imitate Men

I recently started work in a male-dominated field, and I’ve been getting a lot of sympathetic remarks about my being “a woman in X.” But something has started to feel a bit off about this line. I’ve realized that being a woman in my field doesn’t actually feel that hard. I was lucky to be raised by an educated mother, attend a progressive school, and all the rest. Simply being in the arithmetic minority doesn’t feel like any kind of judgment on my right to be here.

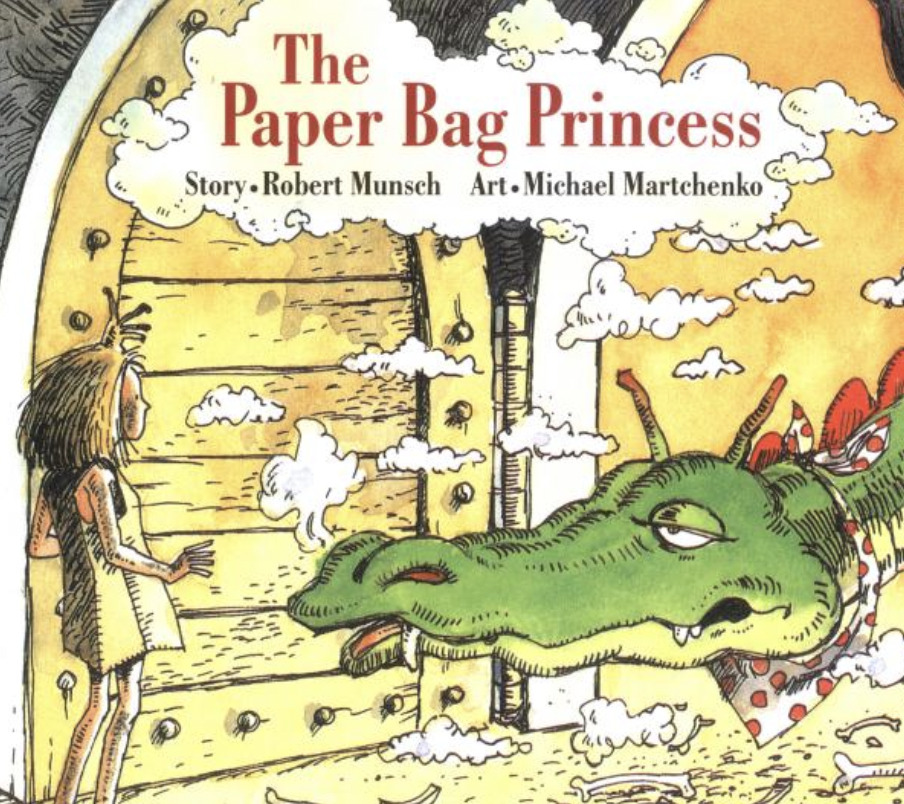

The progressive belief system I grew up with included a heavy dose of so-called “lean-in” feminism. It’s something I internalized early: Even when I was in elementary school, I loved a 1981 children’s book by Robert Munsch called The Paper Bag Princess. A dragon burns away the princess’s dress, leaving her with only a paper bag to wear. Instead of waiting in her tower, she escapes, rescues a prince, and, finding him disappointing, rides off into the sunset alone in a blaze of frumpy glory.

When I think about the empowerment stories we celebrated in my granola school, almost all of them shared that same theme—a free-thinking girl rejects the shallow, repressive trappings of femininity, so she can do something that’s actually worthwhile—i.e., something masculine. Our heroes weren’t “Girl Who Did X Really Well.” They were almost invariably “First Girl to do X Boy Thing.” Rejecting femininity was a moral triumph in itself.

Around middle school, this trope evolved into the “cool girl,” and not just at my woke school: the Jennifer Lawrence or Mila Kunis type of the early 2010s rom-com, who curses and watches football and eats burgers and maybe sleeps around. The “cool girl” isn’t cool because she’s down, she’s cool because she’s genuine. The strong implication is that masculine things are simply more fun and authentic for everyone, and so if other women had the cool girl’s confidence, they’d be tomboys, too. “Girliness” is what purpose, strength, and authenticity exist in opposition to. The heroine must overcome her femininity, not grow into it. She must be Not Like Other Girls.

I loved The Hunger Games as much as anyone. And I definitely identified with the Arya Starks and Hermione Grangers of the printed page and silver screen. I also understand that the linkage between not-like-other-girls tomboyism and internalized misogyny has been a well-established media trope for years. But what concerns me here isn’t misogyny and its message that women are bad, per se. Rather it’s the idea that womanhood itself is purposeless and inauthentic unless you’re behaving like a dude.

For years now, there’s been a popular mainstream-left movement to address the gender gap between high-earning (often tech-oriented) career paths dominated by men, and lower-earning, care-oriented or human-oriented careers dominated by women. This has been run in parallel with a campaign to get more women into those male-dominated spheres.

This, by itself, is great: There are fantastically talented women in engineering who lead fulfilling professional lives that would have been impossible just a few decades ago. But there’s a part of this movement that’s slowly shifted from the idea that “women can do anything” to the idea that women want the same things men do, in equal statistical proportion, and so anything less than 50-50 parity reflects either discrimination or patriarchal brainwashing.

This conflicts with the widely observed phenomenon whereby, even as young as preschool, girls are more likely to express a preference for care-oriented activities, such as nursing or teaching, and enjoy care-oriented toys, such as baby dolls or stuffed animals. Yet contrary to the findings of study after study, a steady drumbeat of culture critics insist that such patterns are mere artifacts of social stereotyping. These critiques are asymmetrical: The idea that girls like baby dolls is seen as insulting, while the idea that boys like cars—not so much.

We could look at the higher number of little girls who aspire to be nurses and say, good for you! You’ve chosen an intellectually and physically challenging vocation that’s essential to human health. Let’s create gender equality not by shuffling people from one profession to another, but by valuing those nurses more—perhaps through, say, paid maternity leave, generous childcare subsidies, and reduced tuition. (I realize that these things already exist in many Western countries. But I’m American.) Instead, we too often say, poor thing, you’ve been brainwashed, wouldn’t you rather be coding videogames? In Politics, Aristotle wrote that a female is an incomplete male, or a deformed one. This outdated slur on females is 23 centuries old, yet it often feels like it’s made a comeback through the back door of progressivism.

This helps explain why so much of the Gen-Z gender-nonconformity movement seems so joyless. Unlike the liberated queers of previous generations, “neogender” types seem focused on fleeing something they regard as distasteful—puberty, sexuality, gender expectations. By my observation, many of the girls who now identify as non-binary simply found it hard to reconcile their complex interior experience with expectations placed upon them. Instead of trying to broaden out the meaning of girldom, they just concluded that they must not really be girls.

I’m speaking as someone in the target audience for empowerment feminism, given my employment in a male-dominated professional field and my nerdy and outdoorsy childhood. I’m grateful for the systematic forms of encouragement that I benefited from, and have a ton of admiration for the feminist heroes whose stories and guidance I grew up with. I would never want that taken away from anyone. But there was also something slightly insidious about the unspoken narrative that went along with it.

When I tried to relate to other girls, I felt like I was signing up for a losing team. But I also grew up in the era of “toxic masculinity,” so when I tried to relate to boys, I felt a suspicion and a defensiveness that served my friendships poorly. At work, it was easy for me to blame social slights on the fact that I was the only woman in the office, instead of maybe as spurs to self-improvement. I was taught that I could learn and achieve anything, and I believed this was true. But all the speechifying I’d endured about power imbalances and pervasive sexism also created bleak expectations for my personal life.

Most of the girls and women who exist in my mind’s eye as I write this essay were people I met at the Ivy League university where I studied as an undergraduate. And from what I can tell, all of the phenomena I’m describing are dramatically more acute at elite colleges, private schools, and the tech companies that hire their graduates than in other social spaces. Many conservatives are apt to blame the progressive pedagogy that dominates these spheres. But I’d also point out another common denominator in the households that produce these high achievers: the prep-school helicopter mother. She’s a Gen-Xer or Boomer who went to college, possibly grad school, and succeeded professionally before having kids. She’s high-agency and high-ambition, while also often existing in a moneyed, coastal social sphere that has allowed her to stay home (or work part-time) while funnelling much of her drive into her children.

She chauffeurs her teenagers to sports in the early morning hours and private instrument lessons after school. She’s probably gone to see the principal to address her kids’ social conflicts on at least one or two occasions. She might drag her sons and daughters to naturopaths and nutritionists to treat their dubious dietary sensitivities. She competes with the other PTA moms in “busyness” and high-performing student prestige. She often is transparently unhappy, guilty, anxious, and bored; and her kids often are, too.

At the PTA events my mom hosted, the dads would stand in circles and brag about the fun they were up to that weekend, while the moms would stand in a different circle and quietly one-up each other about how little fun they were having, how stressed or inadequate they (or their children) were compared to their neurotic standards. The more money they had, the stronger this effect was. These were people who could afford maids. There was actually very little they really needed to do.

Socially malaised Gen Z coastal elites can sense this unhappiness, and intuit that it isn’t good for them. Some of the unsettling forms of acting out you see when it comes to gender are a way of breaking ranks. It’s easy for these people to believe that femininity is purposeless and insincere, because that’s exactly what they observed as children. And one reason they’re obsessed with denying the reality of biological sex is that accepting that reality would tie their destiny to that of their mothers.

No, I’m not arguing that everything would be better if we turned back the clock on feminism, or if we were all a little more “trad.” Women are still settling into a massive shift in the meaning of labor and family structure, and it’s not clear what the future of female identity holds for us. But in the meantime, channelling our frustration into inventing new pronouns and hunting for sexist microaggressions probably won’t make things any better.