Croatia

Remembering the Jewish Yugoslavia that the Nazis Destroyed

The story of how I came to know one of those survivors, and chronicle her life.

I grew up in a non-observant Jewish family. On both sides, my grandparents had emigrated from eastern Europe around the turn of the 20th century. The possibility that relatives we’d lost contact with might have been caught up in the Holocaust was very real, but it wasn’t something we spoke of directly.

In fact, my only personal connection to anyone connected to the Holocaust came about entirely by chance, when I was in my 30s. It had nothing to do with Lithuania or Poland, where my grandparents came from, but rather Yugoslavia, an artificial (and now defunct) country cobbled together out of the Balkan territories of the Austro-Hungarian Empire following its defeat in 1918.

Of the approximately 82,000 Jews who lived in Yugoslavia before the Nazi-led invasion of that country on this day in 1941, only about 15,000 survived. This is the story of how I came to know one of those survivors, and chronicle her life.

My 1950s-era childhood neighborhood of Washington Heights in upper Manhattan was something of a haven for European émigrés who’d fled Nazism. Among a handful of refugees who lived in our apartment building was an older couple, the “Fleshes,” whom I knew only from brief meetings in the lobby when I might hold a door for them. Mrs. Flesch, who was extremely animated and spoke in a raised voice with a thick accent, would say, “Thank you, my boy!”

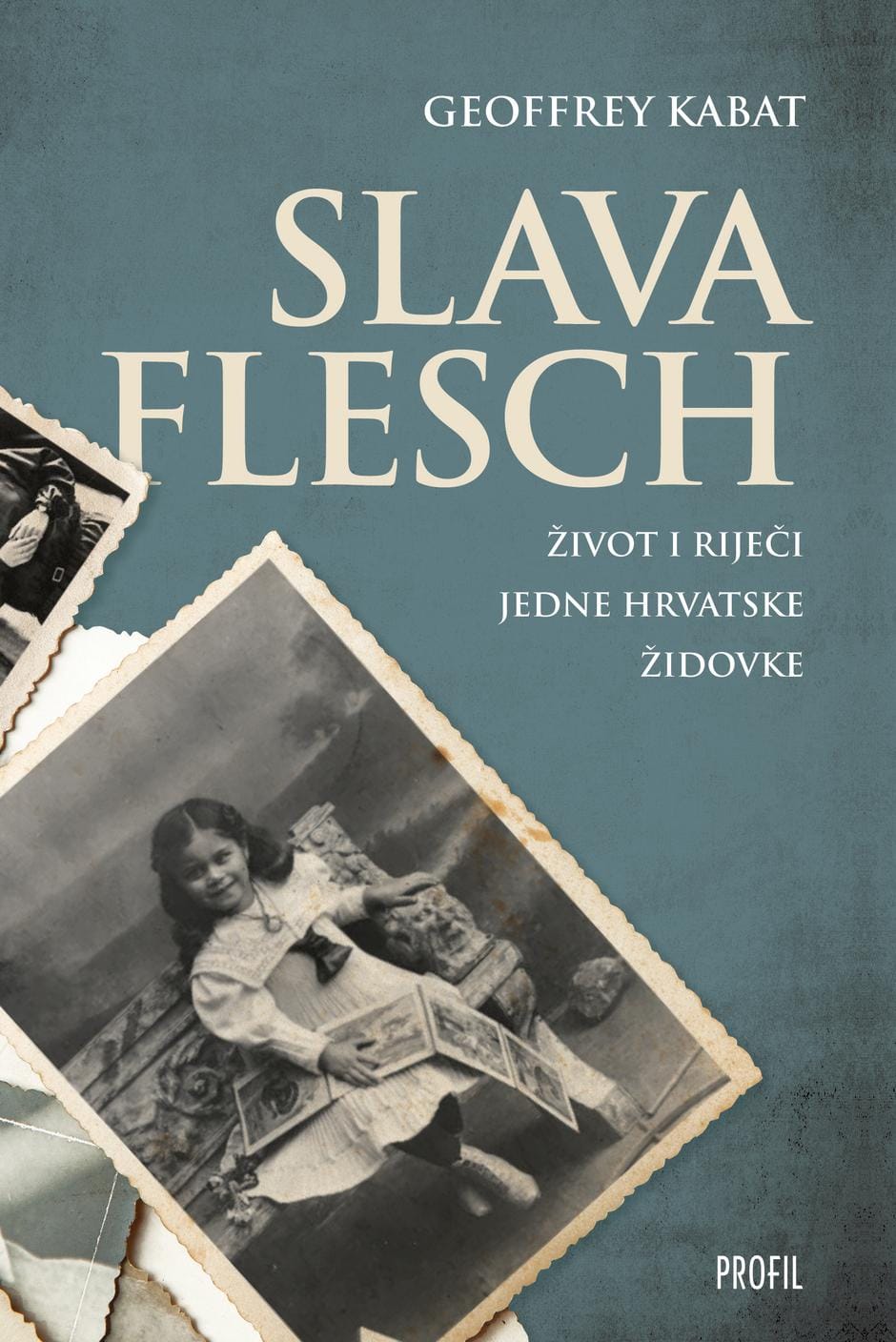

Thirty years later, during a visit to my parents, I reconnected with the Flesches and started visiting them regularly. What drew me in particular to Slava Flesch (1904-1992), who was now close to 80, was her seemingly endless stream of stories and observations about the world she’d grown up in. She rendered a vivid portrait of what life was like for the Jews in the Croatian region of Yugoslavia (as it then was) in the years leading up to World War Two, and during the first year and a half of the war itself.

Although Jews constituted a tiny minority in Croatia, they had long played a vital role in the larger society as managers of estates, merchants, doctors, and lawyers. Slava and her husband Emil were active members within the Jewish community of Sisak, an inland city in central Croatia. Though Sisak is a long way from Vienna and other larger urban centers, they’d prided themselves on being highly cultured, as well as being integrated into the city’s civic life.

When Yugoslavia was occupied by German and Italian troops in 1941, Sisak became part of a Nazi-backed puppet state ruled by the ultranationalist Ustaše movement. Slava’s mother and four aunts, as well as many other people she knew, were rounded up and sent to death camps. Of the roughly 25,000 Jews in Croatia at the time of the Nazi invasion in 1941, only about 5,000 would still be alive when the war ended in 1945.

But Slava herself was not in Croatia when the Nazis arrived. She’d been an only child, precocious from an early age, and alive to the resentment against the Jews that had been simmering just below the surface of polite Sisak society. As a woman in her mid-30s by the time the war started, she’d sensed what was coming for Jews and, unlike many of her friends, had made plans to flee to the United States. At the end of March, 1941, she and her husband, along with her two sons, took a train out of Zagreb, days before the April 6th invasion.

Transplanted to New York, Slava remained connected to her old world, and the fates of the people she knew. Even years after fleeing to America, the world she left seemed uncannily vivid in her mind. Like some kind of time traveler, she seemed to inhabit her own history in real time, a quality that expressed itself as a natural gift for scene-setting and storytelling.

Slava had been taken out of school after the fourth grade, but this never stopped her from reading, observing, and otherwise absorbing what she saw around her. She paid particular attention to regional dialects and to the idiosyncratic habits that marked different strata of society. She wasn’t tribal or parochial in her outlook, and often drew attention to the Serbs who’d died at the hands of the Ustaše, as well as the Jews. At times, she could be irreverent in portraying the foibles and folk delusions of her own Jewish friends and relatives. She was part chronicler, part gossip, part amateur ethnographer.

It wasn’t just her gifts with language and recollection that made her so interesting to listen to. She was also something of a natural actor. At one moment, her voice was flat and detached, the next shrill with indignation, disbelief, anger, then buffeted by laughter—like an audiobook narrator stepping into and out of different characters. I was a captive audience during my visits with her, and had no choice but to hear all that she had to say, from the beginning to the end of each story. By the time I’d decided to write a book about her, I was visiting her once a week. This went on for two years.

A particular quality she had as a storyteller—one shared by many successful novelists and playwrights—is that she always made you feel as if her locus of narration was situated within a large extended sweep of relatives, friends, friends of friends, children of friends, neighbors, as well as people who might never make a direct appearance in any story but were simply part of the richly textured social ecosystem into which you, as the listener, were drawn. Sisak became a kind of Winesburg, Ohio. And whoever’s story she told, whether that of a high-placed diplomat or of the lowliest peddler or beggar, it was as if the details of the story had just been made fresh to her (even if, in truth, she was reciting a second-hand account or even some composite tale stitched together from rumor and supposition).

Some of her stories were conventionally autobiographical. At the age of nine, Slava told me, she’d resolved never to speak again to a teacher who, in a moment of irritation, had used an antisemitic term to refer to Jewish children who were leaving for religious instruction. Many years later, when she was an adult living in Vienna, this same sense of resolution led her to decide abruptly to return to Croatia upon observing (from her own balcony) paramilitary groups stockpiling arms and provisions. (The full narrative has overtones that may remind some readers of The Sound of Music, as her own Vienna landlord was a powerful aristocrat and known supporter of Hitler.) In explaining her resolve, Slava would quote Martin Luther (though she knew him to have been antisemitic, and was well aware of the irony in citing him) to the effect of Hier stehe, ich kann nicht anders: Here I stand. I cannot do otherwise.

The book I wrote about Slava’s reminiscences, an excerpt from which appears below, is not a “Holocaust memoir” because her decision to flee spared her any direct personal contact with the Nazis’ machinery of industrial slaughter. But the Holocaust is a constant presence in the background, because of what happened to her mother, her aunts, and other family members. Some Jews who escaped Europe were reluctant to probe the fates of those they’d left behind, out of fear of what they might find out. Slava took the opposite approach.

Moreover, the Holocaust didn’t entirely overshadow Slava’s fascination with the history of her own Jewish community in Croatia and that community’s relationship with the larger, Christian society. My book charts that history in the century preceding World War Two, typically through multigenerational stories that find their denouements in the tales Slava told of the people she knew and the events she witnessed. Slava’s tales stand in for a larger Jewish Croatian narrative, which is itself a microcosm of the many other Jewish parts of Europe that fell under Nazi rule. In some ways, Sisak is a sort of European everytown, and its fate shows how quickly a peaceable and multicultural society that had existed for hundreds of years can be propelled suddenly into the abyss.

After having lived for 35 years with my transcription of the tape recordings I’d made of Slava, I finally did the work of editing and pruning, then sent the manuscript with my introduction to a number of publishers. I received some warm letters and editorial suggestions, but no one could see it as having commercial potential.

In the end, I wrote to a historian of the Holocaust in Croatia, who also happens to have been Croatia’s ambassador to France and a leader of the small surviving Jewish community in Zagreb. Ivo Goldstein wrote back saying that he knew many of the places Slava described, and found her reminiscences to be very interesting. He volunteered to help raise funds from a Croatian Jewish organization to translate the text from English into Croatian and publish it in book form—an English-version excerpt of which appears below.

In his emails, he referred casually to “our friend Slava,” a three-word testament to the sense of familiarity and warmth that, I hope you will agree, her anecdotes convey.

Excerpt: The Duke of Ratibor

The last years we were in Vienna, we lived in an apartment, which we rented in an eighteenth-century palace. Our landlord was the Duke of Ratibor, a German nobleman from the highest echelons. He was reichsunmittelbar [literally, an Imperial “immediate”], which means that his daughter could marry a Hapsburg. In England, this sort of thing doesn’t exist. Windsors can marry commoners. But in Austria and in Germany, there were nobles who were reichsunmittelbar.

And he was enormously rich. When the first Ebert regime came to power in Germany after the First World War, they took away all the great estates and wealth and factories and coal mines and iron mines from the aristocracy. Everything they had was taken away. They were left with only a small part of their estates. And when Hitler came to power, he promised the aristocracy that he would give them back everything. So they went over to him.

This Duke of Ratibor was married to the granddaughter of the Princess of Metternich. She [the grandmother] was very famous, very bright and very witty. For instance, once she was introduced to King Ferdinand of Bulgaria. And he complimented her on looking so well on her seventieth birthday. And she said to him, “Leave me in peace! I am seventy years old.” And he said, “Seventy years, that’s not so old.” So she answered, “Not for a cathedral perhaps, but for a woman it is.”

Ratibor and his countess wife [known formally as Victor III, Duke of Ratibor; and Elisabeth Prinzessin zu Oettingen-Oettingen und Oettingen-Spielberg] were descended from the highest aristocracy. Some were counts and some were barons. Their titles depended on their age, and on whether they had an estate given to them in the region they came from. This was the thing to have. Otherwise you couldn’t marry a reichsunmittelbar prince or count.

And through her, he inherited this palace. It was built by [Johann Bernhard] Fischer von Erlach, the greatest baroque architect in Vienna. So we lived in this palais that belonged to the Countess and Duke. He was our landlord. They were so beautiful, these aristocrats. I lived there from 1927 to 1934. He had furnished it very beautifully.

This Duke of Ratibor came from Germany and got back all of his holdings in Silesia, his big estates and, most of all, his coal mines. Half of Poland’s coal mines seemed to belong to him. But when he came to Vienna, he didn’t have the whole palais to himself. Most of it was rented out to other people, including us. He had a small apartment in one part of the building that was reserved for him. And the main salons were rented to a music director, who arranged balls and concerts in the palace. His name was Ignaz Mendelssohn. And on the second floor was the Society of Friends. They came from Philadelphia in 1918 to help the children who were hungry and destitute after the First World War. They were very fine people, doctors, and so forth. And we lived on the third floor, the top floor.

There were verandas going around the whole building on each floor. And you could see the people marching in the streets. When the landlord got everything back, he threw his support to the Nazis, and supported a paramilitary organization with [Fatherland Front leader] Ernst Rüdiger Starhemberg.

The palace was very solidly built. It had a deep cellar with three levels and led to the catacombs of Vienna. From my windows, I could see the towers of St. Stefan, the main cathedral—the highest tower in Austria and Germany. And we lived just opposite it. Under the streets, they went under St. Stefan, where there were graves and catacombs dating back to the year 800, where they hid weapons, all kinds of weapons.

The marchers wore a cock’s feather. Starhemberg-Jäger, they called themselves—hunters. But Starhemberg and his people were not as anti-Semitic nor as extreme as Hitler and Ratibor. They decided who was a Jew, but it was not so rigid that if you had a Jewish grandmother or a Jewish grandfather, you were considered a Jew. However, they came to the Jews and put pressure on them to give them money. That was a regular occurrence. A minor official would come to a big Jewish industrialist or merchant and say, “We need some money, and the Duke sends his regards.” And you had no choice but to give.

So we saw all this activity going on around us. From our third-floor gallery, we saw how they were delivering and stockpiling weapons and munitions and medical supplies—everything for the coming war. They were getting organized. This was in 1933, the year Hitler came to power.

When we saw this, we decided to leave. My husband looked down at the crowds—he had his office there—and he said, “In six months I will not be able to practice law. I am a Jewish lawyer.” There were exemptions if one had served in the First World War. My husband was in the army for five years. He was a First Lieutenant. He could have had some consideration under Starhemberg, but not under Hitler. We knew it was promised that Jewish servicemen who could prove that they had been on the front lines would not be treated badly. And my husband had many front-line buddies in the Army. Several times we went to reunions with these comrades of his from the war: coffee klatches in fine restaurants, and dancing. But we didn’t feel comfortable. So, in 1934 we moved back to Sisak [in Croatia].

When we were getting ready to leave, I informed the management that I wanted to sell the tile stove in the drawing room—which was big and tall, like a wedding dress. It was mine. I could prove it.

So the Duke himself came to my apartment, and of course he didn’t sit down—no, no, never—he wouldn’t sit in a Jewish home. He went into the drawing room, and in the corner was the stove. And he looked at it. It was beautiful, and more than two meters tall. And decorated in faience [fine tin-glazed pottery] with white roses.

He said, “Well, I will give you this much for it”—a very minimal sum. I said, “No thank you.” Nein, Durchlaucht, das kann ich nicht verkaufen. (You wouldn’t address him as “Duke of Ratibor.” You had to say, Durchlauchten.) He looked at me—he was a beautiful man, so tall, with such a black beard, cut short, very soigné. And he warned that I wouldn’t get a better price.

So in the end, I took the stove down to Yugoslavia. And the stove is still in Sisak, in a museum, along with my mother-in-law’s brass chandelier. He knew that Austria would fall, and he knew that I was on the run. This was in 1934. Only I had a better nose than most, so I got out in time. To this day, I don’t know how I managed it.

Back in Sisak, we continued to read the Viennese newspapers. In 1938, Austria fell. And then, when the Germans attacked Poland, in September 1939, one of the first things I read was that the first-born son of our Duke [Viktor Albrecht Johannes Josef Michael Maria] was killed in action against the Poles. I wasn’t too sorry. That’s human, you know.