Politics

Ukraine: On the Fault Line Between East and West

Ukrainian nationalism and its clear expression as part of a larger European identity has burst into the open with the power of a hydrogen bomb.

MSNBC’s Joy Reid thinks the West’s galvanizing response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is unfair. “Let’s face it,” she said on March 8th, “the world is paying attention because this is happening in Europe. If this was happening anywhere else, would we see the same outpouring of support and compassion?”

The Western world is indeed less interested in the victims of war in places like Yemen and Syria, but there’s more to the distinction than Reid’s commentary allows. It’s not just that Ukraine is, as Reid put it, “white and largely Christian”—Russia is also mostly white and Christian, yet the vast majority of Westerners would side with non-white, non-Christian Japan (to name just one example) if it suddenly found itself in a hot war with Putin’s military.

A nuclear conflict is also a possibility for the first time since the collapse of the Soviet Union, and no serious person thinks the wars in Syria or Yemen are likely to lead to a global apocalypse. On March 10th, the American Psychological Association published the results of a survey showing that Americans are coping with an “unprecedented” level of stress. Eighty-seven percent of respondents said their mental health is suffering from a “constant stream of crises without a break over the last two years,” and 84 percent described the Russian invasion as “terrifying.”

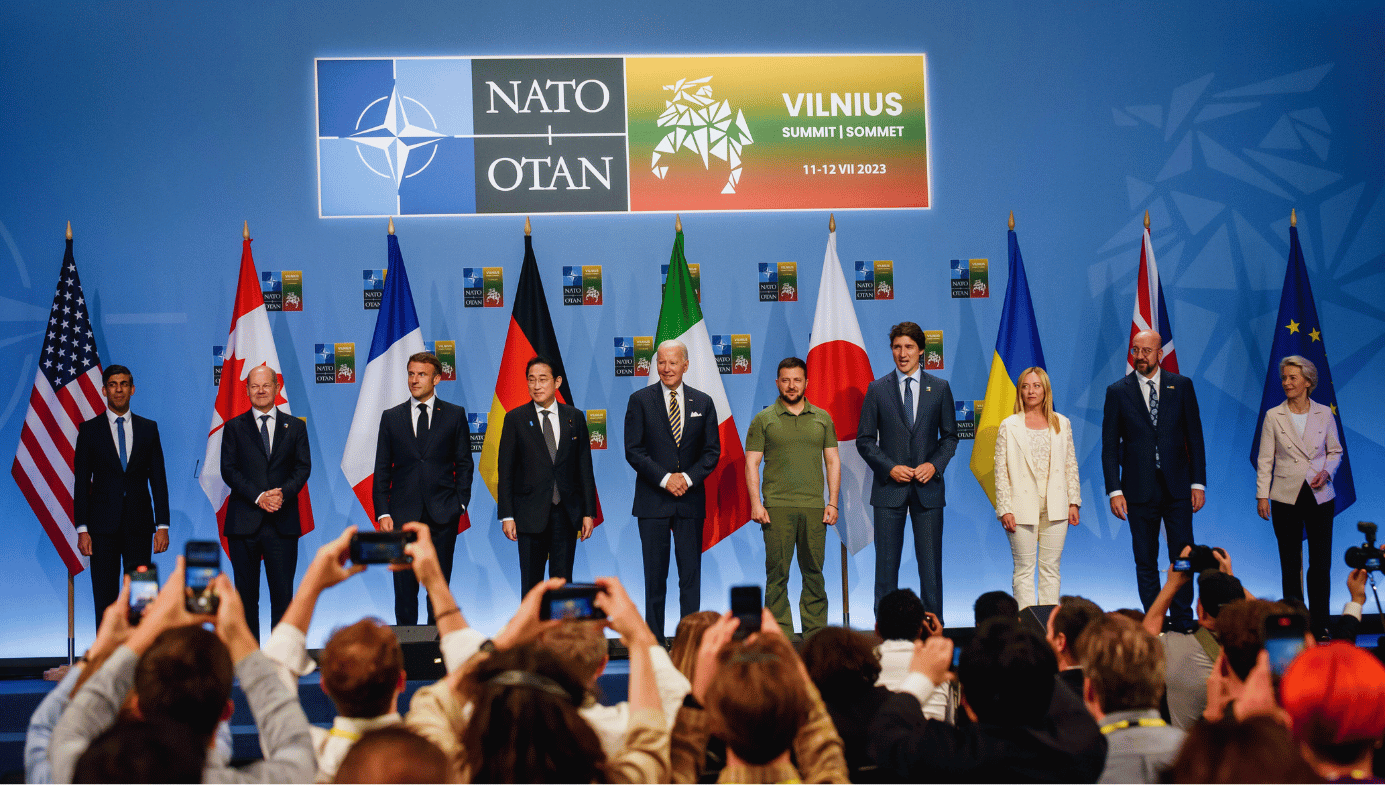

NATO has also been muddling through a crisis of its own for years. However, the war is a historical hinge event that a self-absorbed and malaise-afflicted West couldn’t ignore even if it wanted to. The mauling of an innocent European country provides a vivid and violent reminder of just how dangerous it is to be outside the protection of the West’s security umbrella.

But there’s something else going on, too—something less often spoken aloud but that partly explains why this war is happening. Westerners overwhelmingly sympathize with Ukrainians because we view them as an extension of “us” in a sense that’s both broader and narrower than race and religion: narrower because Ukrainians are Europeans, and broader because they are, or at least aspire to be, part of Western civilization, which in the modern age is not limited to race and religion.

Russia, meanwhile, views Ukraine as part of its civilization. And Ukraine, sitting right on top of this civilizational fault line, is being ripped apart in a geopolitical earthquake.

So, is Ukraine Western? There isn’t (or at least there has not been) a straightforward answer to this question, like there is with, say, the Netherlands (yes) and China (no). I wrote about Ukraine at length in my 2012 book Where the West Ends, a travelogue through the borderlands of the Near East and the former Soviet Union where “the West mixes and coexists with various Eastern civilizations and forms something else—not one thing, but different things in different places, depending on what’s being blended.” The West doesn’t abruptly end anywhere in Europe. It falls away in degrees.

In the fall of 2012, my best friend Sean LaFreniere and I drove a cheap and soon-to-be-battered Romanian car across a remote Polish border outpost into Ukraine. The Polish border guard stamped our passports, widened his eyes, and warned: “It is very strange over there.” It certainly was. At first, I felt like we had abruptly crossed the farthest frontier of Western civilization. The largely empty rural roads to Lviv were so poorly maintained they looked like they’d been shredded by air strikes.

We drove through remote settlements at midnight without any electricity. If not for the pedestrians appearing wraith-like at the edges of our headlights, the landscape would have looked like a scene from the History Channel’s documentary series Life After People. I’d never seen anything quite like it—certainly not in Europe—but Sean had. “This is exactly like Russia,” he said. “Exactly.” I had not been to Russia, but he had, and the drive from the Polish border toward Lviv eerily reminded him of a nighttime trip he had taken from Moscow to St. Petersburg.

But when we finally reached Lviv, the largest city in western Ukraine, neither of us felt like we were in Russia. It was as if we had driven through a hole in the space-time continuum and arrived in Europe a hundred years earlier, before any postwar or post-communist progress had been made. In the city center, retail establishments, restaurants, and other forms of commerce were scarce. It was strangely quiet because so few people owned cars. Were the roads so bad because hardly anyone drove? Or did hardly anyone drive because the roads were so bad? “Rush hour” consisted of a mass of commuters taking the tram or walking to work.

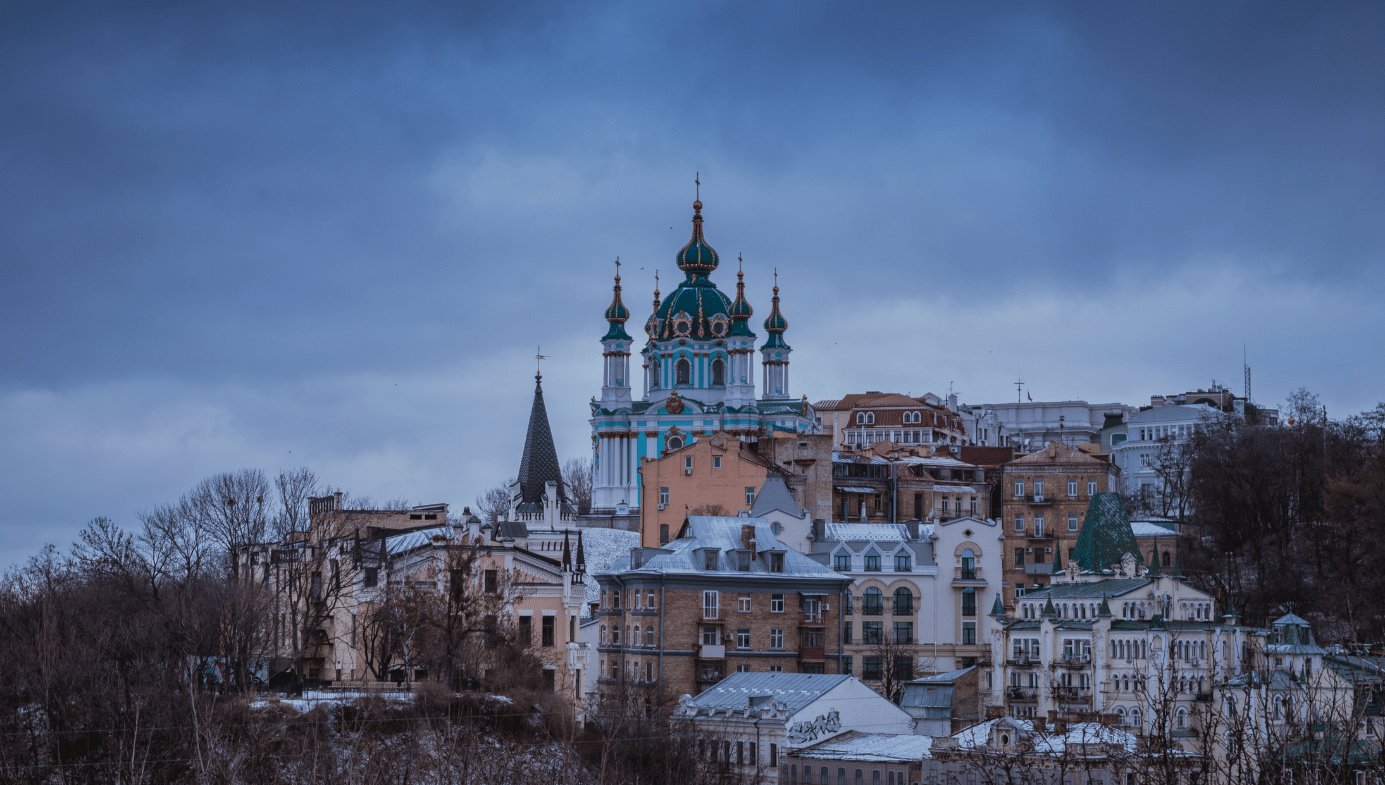

Lviv, long a stronghold of Ukrainian nationalism, certainly felt different from the European Union nations to its west, but it did not feel Russian, not even faintly. The historic urban center dated to the Polish and Austro-Hungarian periods and included baroque, renaissance, and classic styles of architecture rather than the Russian Gothic Revival style and onion domes common in the old Russian empire and in the Ukrainian capital, Kiev. Lviv was then and remains a long-lost cousin of Europe much more than of Russia.

But in the center of the country, Kiev looked, sounded, and felt Russian to my foreign senses. Magnificent imperial architecture was everywhere, and more people spoke the Russian language than Ukrainian. A police officer who stopped me for a minor infraction angrily demanded (in English) that I speak to him in Russian. The old city was a tsarist gem, but the poorer eastern side was a communist-blasted Soviet disasterscape of imposing apartment towers built by totalitarian architects for Homo Sovieticus—the Soviet “New Man” without history, national identity, or culture; a cog in a brutal industrial machine made of human parts.

Of course, none of this meant that Kiev was Russian any more than Dublin is English just because the Irish speak the same language and have similar-looking buildings in the old quarters of town. We drove south to the Black Sea and into Kherson, a city ground beneath the Soviet wheel and now occupied (again) by the Russians. Much of the city and countryside was backward and bleak, with rusted and abandoned industrial plants, defunct smokestacks, and agricultural fields plowed with animal and human labor rather than with machines.

I didn’t blame the Ukrainians for making a hash of the place. Russian communists did that to them, and the Ukrainians couldn’t dig themselves out in a day. Many communist-battered countries in Europe managed to climb out of the crater into which Moscow’s bulldozer had pushed them, thanks in part to the European Union. But Ukraine remained under Moscow’s long shadow, just a bit too distant for the Western cavalry to rescue.

When we reached Odessa, everything changed again. Ukraine’s jewel on the Black Sea was another world entirely—not really Russian, not fully Ukrainian, and certainly not Soviet except in the dreary asteroid belt of towers surrounding the historic center.

Russian Empress Catherine the Great established Odessa after snatching the Sanjak of Özi from the Turks in 1792. The city back then was Russian but not Russian, starting with its Greek name after the ancient city of Odessos. Settlers flooded in—not just Russians but also the French, Germans, Mennonites, Italians, Jews, Poles, Bulgarians, Romanians, Tatars, Turks, Moldavians, and of course Ukrainians—and it was a free port until 1859. Today, it is mostly Russian-speaking with an ethnic Ukrainian majority, and it retains the spirit of the coastal liberal entrepôt that it always has been.

Finally, we set up camp in Crimea for a while, two years before Russia annexed it in 2014 (an event I predicted in my book). Nowhere in Ukraine felt as flamboyantly Russian, even when it was still at least nominally governed from Kiev. The Russian Black Sea fleet was based in Sevastopol. Russian flags snapped in the wind even then, not just in Sevastopol but also in Yalta, where a statue of an angry Vladimir Lenin still stood (near a McDonald’s) and where I heard the Russian national anthem playing on the waterfront.

Crimea defiantly placed itself in Moscow’s time zone despite being due south of Kiev. More than two-thirds of the region’s population is Russian, making Ukraine’s recovery of Crimea unlikely. I sometimes forgot which country I was in, whipsawed back and forth in a land that seemed to have no firm sense of its identity or its place in geopolitical space—an unmoored and wounded patchwork with its internal contours shaped by the detritus of expired empires.

Sean and I didn’t venture farther east, but we knew that some of the Ukrainian cities east of Crimea had large ethnic Russian populations—around 50 percent in Mariupol, for instance—and that roughly 40 percent of the Donbass region was ethnically Russian. Had I been asked, 10 years ago, to draw a civilizational boundary that allowed me to define the West as broadly as possible, I’d have probably drawn it vertically through the center of Ukraine, with western Ukraine faintly Western and eastern Ukraine more Eastern than not. Russian stooge Viktor Yanukovych had been elected president just two years before, and hard as it is to believe now, Vladimir Putin was popular in most of Ukraine at that time.

Civilizations are loosely defined by a host of factors, including language, religion, ethnic and cultural identity, historical experience, stories that people tell themselves about themselves, feelings of in-group solidarity, and so on. All of these things are subject to change, sometimes at glacial speed, sometimes suddenly.

The part of our planet that stretches from Europe’s Baltic Sea to the Black Sea and the Eastern Mediterranean has long been a bleeding and burning borderland between empires of the East and the West. History and identity have accumulated in geological layers, with empires conquering new lands and leaving pieces of themselves behind after they withdraw or are conquered in turn.

Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarussians have long been related through their common ancestry with Kievan Rus, a medieval proto-Russian state founded in the ninth century after the Viking-descended Rus’ Khaganate moved its capital from Novograd to Kiev—an area once ruled by semi-nomadic Turkic Khazars from Asia. By the 11th century, Kievan Rus had vastly expanded to include much of what is now northern Ukraine, Belarus, and European Russia. Then the Mongols invaded and shattered the kingdom in the 13th century.

Kievan Rus no longer exists, but Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine are its children. They have things in common with one another that they don’t share with others. Yet they’ve also diverged in significant ways. Like the Russians, Ukrainians were, for a time, part of the Mongol Empire and the Soviet Union, but unlike the Russians, many of them (those in the western part of the country) belonged to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Austro-Hungarian Empire of the Habsburgs.

Even so, Russians, Belarussians, and Ukrainians all considered themselves people of the East as recently as the Cold War. Or, if the Ukrainians didn’t, we heard precious little from them about it one way or the other because they had no autonomy and no power, not even a voice. They fought a war of independence from 1917 to 1921 during the Russian Revolution and briefly established an independent state, but the Red Army reconquered it in 1921 and engineered it into a grim Soviet Socialist Republic. In the early 1930s, Josef Stalin, in an attempt to extinguish Ukrainian nationalism and identity once and for all, devised one of the most notorious peacetime genocides in history by using famine to murder millions.

In 1991, more than a half-century later, after European communism had finally expired, 92.3 percent of Ukrainians voted for independence from the Soviet Union. A week later, the Soviet Union collapsed. This in and of itself did not transform Ukraine into a Western country. While most former communist states in Europe joined the European Union and NATO, Ukraine remained aloof in a strange sort of limbo.

Vladimir Putin clearly sees Ukraine as a part of greater Russian civilization. “Ukraine is not just a neighbouring country for us,” he declared in a speech recognizing the separatist regions of Donbass on February 21st, 2022. “It is an inalienable part of our own history, culture and spiritual space. These are our comrades, those dearest to us—not only colleagues, friends, but also relatives, people bound by blood, by family ties.” Putin wasn’t wrong to acknowledge that shared history, which goes back more than a millennium, but his statement was also self-serving nonsense. No one attacks cities where their dearest comrades live. You won’t see Americans invading Canada. But Putin doesn’t think Ukraine is a neighboring country. He doesn’t think it’s a country at all—he believes it belongs to Russia and therefore to him.

Ukraine begs to differ, and it’s hard to understand the Russian invasion without first understanding why the Ukrainians overthrew President Viktor Yanukovych during the Maidan Revolution in 2014. In 2013, Yanukovych broke a promise he had made and refused to sign a free trade and political association agreement with the European Union. Instead, he vowed to integrate the country with Putin’s Eurasian Economic Union that consists entirely of former Soviet “republics.” For that, and for deploying the sinister Berkut riot police against peaceful demonstrators, killing 108 and injuring more than a thousand, Yanukovych was ousted and tried and convicted in absentia for treason. Ukrainians fought and died in their own capital city for the right to integrate with the European Union, the first people in history to do so. Today they’re doing the same across the country.

They’re likely to succeed in the long run. On February 28th, the fourth day of the Russian invasion, Ukraine formally applied for fast-tracked European Union membership. The process usually takes years, but some European leaders backed Ukraine’s admission immediately. On March 10th, all agreed that Ukraine can begin the long process of joining. At the same time, at least some Ukrainian Orthodox churches want to break ties with their Russian patriarch for backing the Russian invasion (in part, the ludicrous figurehead says, because of Western pressure to allow gay pride parades.)

Ukrainian nationalism may have been muted before, smothered beneath Russia’s tyrannical internationalism as Belarussian nationalism remains to this day. But with the onset of the Russian invasion, Ukrainian nationalism and its clear expression as part of a larger European identity has burst into the open with the power of a hydrogen bomb. No matter what else happens, Ukrainians will remember this chapter in their history for hundreds of years. It’s difficult to imagine these people ever turning toward Russia and the East again.