Politics

Ukraine and the Pro-Putin Right

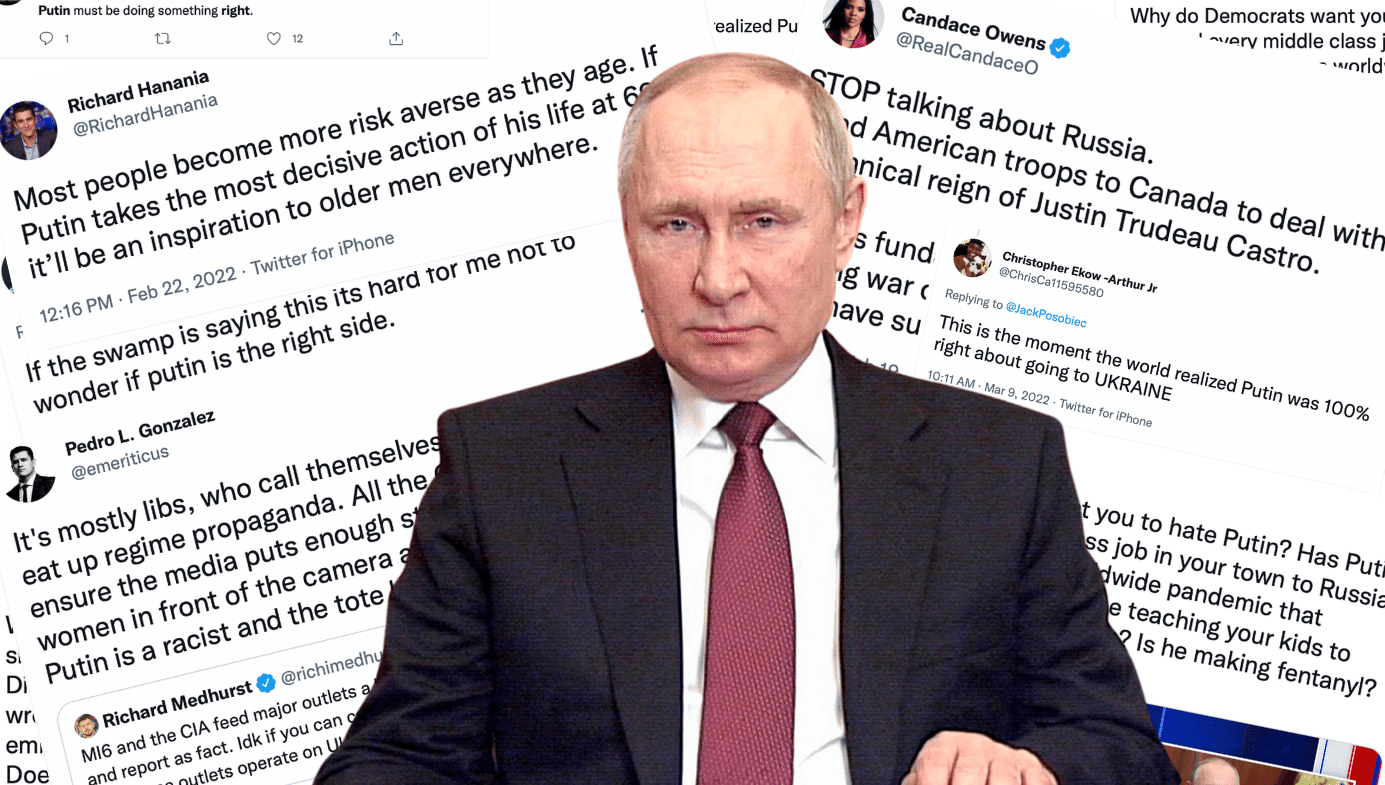

Reactions to Russia’s war in Ukraine have become a perfect demonstration of the “horseshoe theory,” according to which the extremes of Left and Right must converge. Amid overwhelming international condemnation of Russia and sympathy for the Ukrainians’ courageous resistance, Putin-friendly voices blaming the West, NATO, and particularly the United States for the invasion have come from the usual left-wing opponents of American and Western “imperialism” (including the Democratic Socialists of America) and from right-wing opponents of “globalist elites.” But in this instance, the voices on the Right have been louder and more numerous.

On February 23rd, as Putin ordered Russian troops into Eastern Ukraine and President Joe Biden announced the first round of sanctions, Fox News host Tucker Carlson delivered a stunning monologue on his highly rated show, in which he claimed that Americans had been brainwashed into regarding Putin as their enemy. Pushing every hot button of the culture wars and dismissing Putin’s attack on Ukraine as a “border dispute,” Carlson urged his viewers to ask themselves:

Why do I hate Putin so much? Has Putin ever called me a racist? Has he threatened to get me fired for disagreeing with him? Has he shipped every middle-class job in my town to Russia? Did he manufacture a worldwide pandemic that wrecked my business and kept me indoors for two years? … Is he trying to snuff out Christianity?

This sermon pleased the Kremlin so much that it was later replayed, with a subtitled translation, on state-controlled Russian television.

It was hardly the first time that Carlson had weighed in on the Kremlin’s side of the conflict. “Why shouldn’t I root for Russia? Which, by the way, I am,” he declared back in 2019. Last month, just a few days before the invasion, he jeered at “Democrats and some low-IQ stooges in the Republican Party” who were arguing that Americans had a “moral obligation … to support the nation of Ukraine in its battles against Russia” because Ukraine is a democracy. It was really, he argued, all about President Biden’s son Hunter being handsomely paid to lead a “massive lobbying effort” on Ukraine’s behalf. (Apparently, that explains why Congressional Republicans pushed for weapons to be sent to aid Ukraine’s fight against Russia-sponsored separatists in the eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk in 2014, while the Obama administration opposed such a move.) Carlson then invited his guest, political scientist Richard Hanania, to explain that Ukraine is not a democracy at all but a “dictatorship” because, among other things, it has shut down TV channels that broadcast Russian propaganda.

After the invasion, Carlson tried to backpedal, not only condemning Russian aggression but complaining that he was being unfairly accused of backing Putin. Before long, though, he flip-flopped again and went so far as to accuse the Biden Administration of deliberately provoking war with Russia (although he confessed that he didn’t know why Biden would do such a thing).

The problem isn’t just Carlson; it’s that his stance reflects a much larger trend on the Right, at least among the punditocracy—and not just its far-right fringe inhabited by the likes of Jim “Gateway Pundit” Hoft. The Putin apologists, “anti-anti-Putinists,” “both-side-ists,” “whataboutists” and recyclers of Kremlin talking points include Twitter firebrand Candace Owens, talk-show host Jesse Kelly, Newsweek opinion editor Josh Hammer, Federalist editor-in-chief Mollie Hemingway, and “national conservative” eminence Sohrab Ahmari.

Ahmari’s commentary on the subject offers a particularly vivid example of pro-Kremlin spin masquerading as balanced analysis. For instance, his article in the American Conservative on February 28th opens with the stipulation that “Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a very big deal and a very bad thing”; but having cleared his throat with that disclaimer, he launches into an extended condemnation of Western “mass hysteria.” Ahmari cautions against “confrontation with a mighty Eurasian civilization with wounded pride” (note the reverent language) and nuclear weapons; complains that we are “bombarded with one-sided, emotionally gripping images”; and chides “[t]he usual hawkish suspects” for “feeding the dream of a hopeless Ukrainian resistance,” thereby “deepening the Ukrainian people’s pain.”

Two weeks earlier, before the invasion, Ahmari was peddling the Russian propaganda trope that Ukraine’s defense forces are crawling with neo-Nazis (a claim that just a few years earlier he had sought to correct), in an article that failed to mention that Ukraine’s President is Jewish. (As I have written elsewhere, the far-Right extremism problem in Ukraine is real; but the Russia-backed eight-year war in the country’s eastern regions has helped perpetuate it, and pro-Russia separatist forces have themselves been a magnet for Russian ultranationalists and neo-fascists.)

In an article for Newsweek on March 4th, Hammer followed a similar template, acknowledging from the outset that “Putin is, obviously, a thug” and that “[i]n this war, the Ukrainians are the clear victims and the Russians are the clear aggressors,” only to follow those claims with a recitation of caveats designed to weaken them: actually, Ukraine is “just as corrupt and just as oligarchic as Russia, if not more so”; its 2014 revolution was “clandestinely abetted by liberal NGO types”; one of its oligarchs was “a massive donor to the Clinton Foundation”; and Zelenskyy “was at the center of President Donald Trump’s first (entirely bogus) impeachment.” (Trump was impeached for trying to strong-arm Zelenskyy into providing dirt on Biden by using military aid as a bargaining chip.)

While Hammer grudgingly concludes that it’s in “U.S. national interest” to keep Ukraine from being reduced to Russia’s vassal state, his comments on Twitter have almost uniformly derided pro-Ukraine sentiment. He has even suggested that a Miami skyscraper displaying the yellow and blue colors of the Ukrainian flag is a sign that expressing support for Ukraine indicates membership of a “cult.” And then there’s this gem of both sides-ism:

1. Putin is a murderer and thug.

— Josh Hammer (@josh_hammer) March 4, 2022

2. Zelensky is trying to bait easily duped Westerners into a catastrophic conflict.

These two things can both be true.

Of course, plenty of people who are not Kremlin sympathizers have warned that Zelensky’s call for NATO to impose a no-fly zone over Ukraine could be a prescription for disaster. But, as a number of replies to Hammer pointed out, it’s entirely possible to make this case without suggesting that Zelensky is deliberately trying to “bait” or “dupe” Westerners into starting a horrifically destructive war, rather than making an emotional plea out of desperation. Hammer’s interpretation turns Zelensky into one of the bad guys and implicitly equates him with Putin: Sure, Putin may be a murderous thug, but Zelensky is the one trying to get us all killed.

Richard Hanania is another interesting case study. While his politics can be difficult to categorize, his desire to see the US renounce its role of superpower in favor of “99% retrenchment” has attracted a good deal of approval on the isolationist Right. His hope of seeing US foreign policy objectives thwarted, however, has also led him into de facto pro-Putinism and produced some dismal analysis, in which the wish has become the father of every thought. At the end of February, Hanania conceded that his confident pre-invasion prognostications of a swift Russian victory and minimal Ukrainian resistance had been wrong and were evidence of “motivated reasoning.” That admission, however, has not blunted his urge to circulate Russian propaganda and uncorroborated allegations of Ukrainian war crimes, denounce US sanctions policy, and pour scorn on the Ukrainian resistance effort—Russian TV broadcasting in occupied areas, he has speculated, could soon reverse Ukrainians’ loyalties.

So, why are many conservatives either straddling the fence on the war in Ukraine or openly supporting the Russian side? Surely, a resurgent Moscow led by a former KGB officer with imperial ambitions and pretensions to ideological rivalry with Western democracies should inflame every Cold War instinct on the Right.

There are several factors at play. A number of “paleoconservatives” and “national conservatives” of more recent vintage—traditionalists who favor authoritarian cultural norms, a strong role for religion in society, and an inward-looking nationalism—regard Putin as a sympathetic champion of values not dissimilar to their own. In the summer of 2014, shortly after the Russian annexation of Crimea, the elder statesman of the paleocons, veteran pundit and former Nixon advisor Patrick J. Buchanan, penned a column in which he sounded positively enthralled by Putin’s speeches portraying Russia as a Christian country “standing against a decadent West”:

With Marxism-Leninism a dead faith, Putin is saying the new ideological struggle is between a debauched West led by the United States and a traditionalist world Russia would be proud to lead.

In the new war of beliefs, Putin is saying, it is Russia that is on God’s side. The West is Gomorrah.

Buchanan seemed to endorse this view without too many reservations. “In the culture war for the future of mankind,” he wrote, “Putin is planting Russia’s flag firmly on the side of traditional Christianity” and against a West that had embraced the “sexual revolution of easy divorce, rampant promiscuity, pornography, homosexuality, feminism, abortion, same-sex marriage, euthanasia, [and] assisted suicide.” (Wherever Putin may be planting Russia’s flag, the real Russia has the world’s highest abortion rate—despite recent drops—and the third highest divorce rate, while the United States ranks 13th.)

Three years later, in a speech at the Hillsdale College National Leadership Seminar in Phoenix, Arizona, Claremont Institute senior fellow Christopher Caldwell made the remarkable declaration that Putin “is a hero to populist conservatives around the world and anathema to progressives.” Interestingly, Caldwell acknowledged Putin’s likely connection to the murder of journalists and political opponents as well as his suppression of peaceful protests and other forms of dissent; but he also wrote that “if we were to use traditional measures for understanding leaders, which involve the defense of borders and national flourishing, Putin would count as the pre-eminent statesman of our time.” Putin, Caldwell concludes, “has become a symbol of national sovereignty in its battle with globalism.” Consciously or not, this line echoes the “sovereign democracy” doctrine that briefly became fashionable in Russia’s elite political circles in the late 2000s; its core idea was that Russia’s “democracy” had to be accepted as legitimate, whether or not it fit Western standards of democratic governance.

But the details of Caldwell’s acclamation are debatable and frequently tendentious. His claim that Putin rebuilt Russia’s military looks particularly unwise now that the army is apparently bogged down in Ukraine despite its superior numbers. He asserts that Putin “restrained the billionaires who were looting the country,” but it’s more accurate to say that the Kremlin strong-armed some of them into uncritical political allegiance and replaced the rest with cronies. Caldwell’s claim that Russians “revere” Putin must be weighed against the Putin regime’s concerted effort to fill the media space with nonstop agitprop and neutralize all possible political rivals, and also against polls showing that his popularity may be shallow and fragile. But what’s most remarkable about Caldwell’s essay is his obvious view that political leaders should be judged by standards that predate (and in many ways clash with) modern, Enlightenment-derived beliefs about liberty, self-government, and human rights.

While Caldwell focuses on national sovereignty above all, social conservatism is also a key theme in his essay; he sarcastically points out that Putin “is not the president of a feminist NGO [nor] a transgender-rights activist” and later mocks the West’s preoccupation with the ban on “gay propaganda” and the jailing of Pussy Riot, the feminist punk rockers prosecuted for “hooliganism motivated by religious hatred” over a protest performance in a Moscow cathedral. (Incidentally, Caldwell misstates the facts of the case, claiming that the young women “disrupted a religious service with obscene chants about God”; there was no service at the time, the cathedral was nearly empty, and the women’s “punk prayer” song was directed at Putin and at Patriarch Kirill, the pro-Putin leader of the Russian Orthodox Church.)

The same themes are common in Russia-sympathetic conservative commentary today. On the eve of the Ukraine invasion, former Trump advisor Steve Bannon speculated on his podcast that anti-Putin liberals only hate Putin because he’s “anti-woke” and because “they don’t have the pride flags” in Russia. Two days later, Christopher Bedford, a senior editor at the Federalist and vice chairman of Young Americans for Freedom, wrote that if many conservatives aren’t particularly incensed by Putin’s attack on Ukraine, it is because “a lot of us hate our elites far more than we hate some foreign dictator.” After cataloguing the sins of the “elites”—the usual culture-war catalogue of “drag queen story hours,” vaccination and mask mandates, church closures, and police defunding—Bedford makes it clear that he and like-minded conservatives not only regard Putin as the lesser evil but find him positively admirable in some ways. For instance, he writes, while American and Western European elites reject patriotism and treat their countries’ history, heroes, and religion with contempt, “Putin has no such qualms about his own civilization,” a confidence conservatives can only envy: “Why don’t our leaders have the same?”

There are plenty of good reasons to reject progressive demonization of Western history as a parade of racist and patriarchal horrors; but that does not require the delusional belief that Putinism offers a preferable alternative or that (to quote Hanania) a “China-led world order would be a more humane one.” Nevertheless, “post-liberals” such as University of Notre Dame political scientist Patrick Deneen clearly believe that Putin’s Russia represents the more sympathetic side in its ideological conflict with the West. When Patriarch Kirill declares that Russia’s “special operation” in Ukraine is part of a “metaphysical struggle” against a system of globalist domination in which “holding a gay parade” is a test of loyalty to a civilization that offers “excessive consumption” and “illusory freedom,” many American traditionalists are happy to nod their agreement.

Meanwhile, Ukraine’s heroic fight for independence is treated with suspicion by the same conservatives who celebrate national sovereignty as the highest value. This is partly because present-day Ukrainian nationalism is wrapped up in aspirations to be part of liberal Europe: The protests that eventually led to the ouster of pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych in early 2014 were sparked by Yanukovych’s rejection, under Kremlin pressure, of a European Union trade deal widely seen as putting Ukraine on a path toward EU membership (hence the protest movement’s “Euromaidan” moniker).

The fact that this pro-European revolution was openly supported by US Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland, and by many liberal Western non-governmental organizations, has only reinforced anti-Ukraine sentiment among nationalist/populist conservatives. According to Claremont Institute fellow David Reaboi, “Ukraine is ground zero for an ecosystem of influence that, for about a decade, has been able to wield tremendous consensus-making power within the American and western foreign policy community.” That “ecosystem” includes the so-called “Deep State” and what Reaboi calls “the NGO archipelago.”

A particularly bizarre article by Lee Smith in Tablet magazine recently argued that the Euromaidan revolution of 2014 was a “tech-savvy and PR-driven regime change operation” orchestrated by Obama administration staffers and the “national security establishment”—and that Trump’s impeachment over “Ukrainegate” was intended to stop him from uncovering these nefarious maneuvers. Biden’s ascension to the presidency, Smith writes, reinforced “Putin’s sense that Ukraine needed to be put in its place before it was used yet again as a weapon against him.” The belief that Ukraine needs to “understand its true place in the world as a buffer state” between Russia and Europe is shared by Smith himself.

Smith’s piece illustrates the extent to which loyalty to Trump informs pro-Russia, anti-Ukraine sentiment on the Right. Many pro-Trump conservatives have slipped into the habit of seeing anti-Putin sentiment as mindless hysteria in response to allegations that Putin helped Trump win the 2016 election. They also dislike the present Ukrainian leadership due to its connection to Trump’s impeachment and to the belief that the “Biden crime family” is in Ukraine’s pay.

To these ideological and partisan sympathies, one can add the reflexive and visceral mistrust of “establishment” media now prevalent on the populist Right. That the mainstream media have demonstrable problems with credibility and bias hardly obviates the overwhelming evidence of Russia’s horrific aggression in Ukraine. But a penchant for conspiracy theories is a trap into which dissenters from establishment narratives are prone to falling. As is so often the case with self-described “skeptics,” their skeptism only runs in one direction, and leaves them vulnerable to bloody-minded contrarianism. As Christopher Hitchens once remarked, it is a mistake to let your enemies do your thinking for you:

I don’t like Putin, but if you think you’re going to make me hate him like I hate the Left, you’re way wrong.

— David Reaboi, Late Republic Nonsense (@davereaboi) February 27, 2022

The authoritarian trend on the Right is deeply troubling. So far, it has few adherents in the Republican Party absent Trump himself: on March 9th, only 15 House Republicans out of 213 voted against a resolution banning US import of Russian oil and imposing new sanctions against Russia. One of the “nays,” Rep. Madison Cawthorn of North Carolina, was also caught on video calling Zelenskyy a “thug” and claiming that the government of Ukraine is “incredibly evil” and promotes “woke ideologies”—a statement that immediately received strong pushback from other House Republicans. Even so, the strong pro-Putinist currents swirling in the right-wing media and in portions of the activist base could be a portent of future political shifts.

The greatest irony of all, perhaps, is that the Western democracies’ powerful response to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine is precisely the kind of thing the “anti-woke” should celebrate—at least if they are genuinely committed to freedom. It is a perfect moment to push back against progressive narratives that denigrate the West and dismiss liberal democracy as little more than a façade for racist, misogynist, and homophobic “systems of oppression.” It is a moment when democratic capitalist countries are at last, perhaps for the first time since the early 1990s, rediscovering their identity as the Free World—and when the global tide of illiberalism could be reversed.

You'd think that people who consider themselves patriotic Americans and friends of liberty would cheer for these developments. But, as conservative writer Nick Clairmont recently remarked to me, some national conservatives seem to hate contemporary America so much that they instinctively wish its enemies well.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that 17 House Republicans voted against new Russian sanctions. It was, in fact, 15 Republicans and two Democrats. Apologies for the error.