Art and Culture

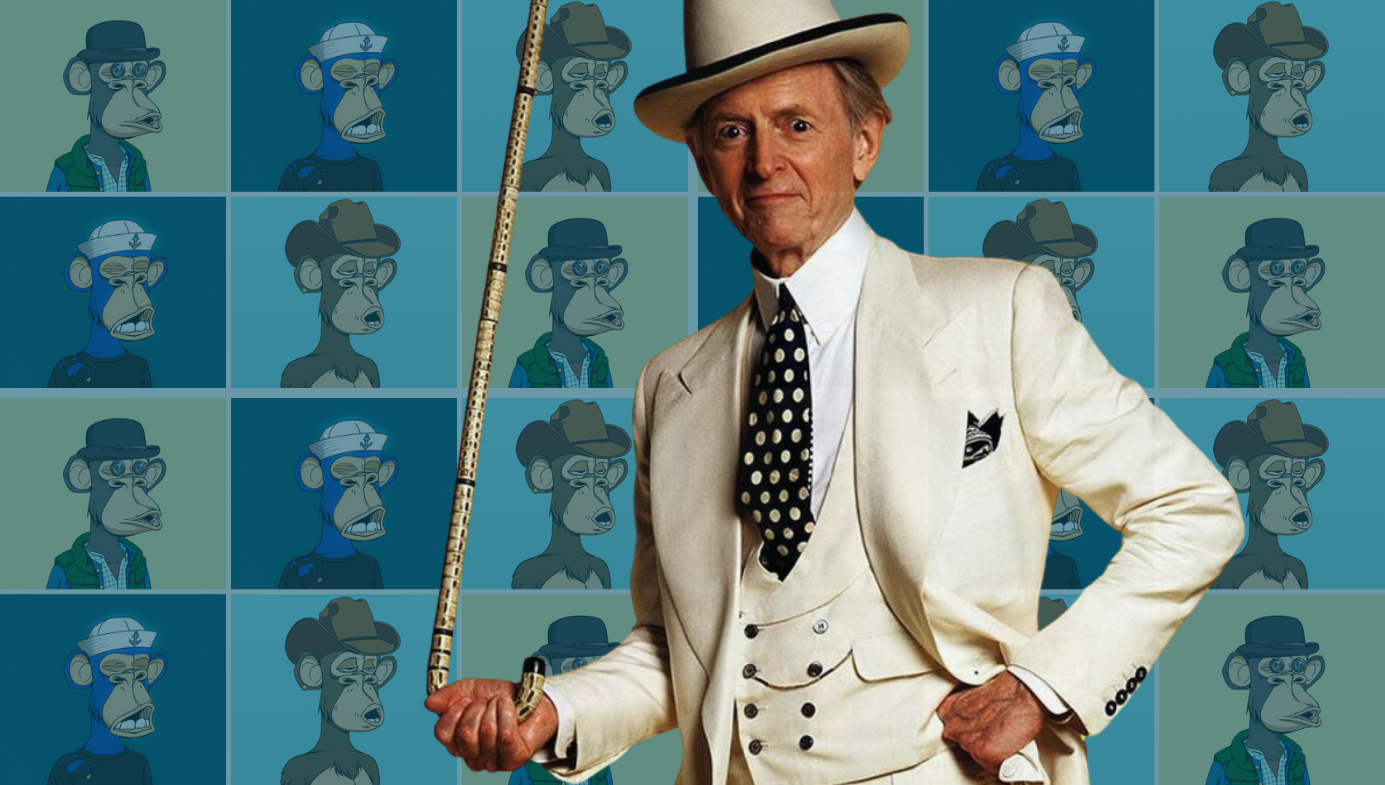

Against De-Materialization: Tom Wolfe in the Age of NFTs

You cannot lose, you cannot win: the present includes the past and the future.

~Marshall McLuhan

I

In the summer of 1970, TV-Ontario filmed Tom Wolfe in conversation with Marshall McLuhan on the lawn of McLuhan’s home in Toronto’s Wychwood Park. Towards the end of their amicable chat, Wolfe complimented his friend on the uncanny accuracy of his predictions from the early 1960s. In response, McLuhan joked: “I’ve always been very careful not to predict anything that had not already happened.” This was not false modesty, since one of McLuhan’s intellectual strengths was his ability to identify significant cultural developments in their most incipient, germinal form. And from our 21st-century perspective, it is clear that Wolfe shared this talent, for the tentative trends and tendencies he described in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s are now reaching fruition.

We are approaching the first anniversary of a landmark event in the art world. Although it seemed shockingly new last year, it represents the culmination of a trajectory described by Wolfe half a century ago: the de-materialization of art. On March 11th, 2021, a momentous auction was held by Christie’s. It was a dramatic departure from precedent, partly because its realized price was a record-breaking $69,346,250, but mostly because the lot that commanded this fortune was not a painting by Vincent Van Gogh, or even a sculpture by Jeff Koons, but a purely digital artwork by an artist with no prior auction record. Everydays: The First 5000 Days exemplified a brand-new aesthetic genre: it was a Non-Fungible Token (NFT), created by Mike Winkelmann, who works under the pseudonym “Beeple.” Neither of these names meant a thing to the fine art world a year ago. They do now.

The artwork, Everydays: The First 5000 Days, is not only the most expensive NFT ever sold, but also the third most expensive artwork sold by a living artist, and the first NFT to be sold at a fine art auction house.#NFT pic.twitter.com/HEZU4zIG6t

— Lucas NFT😈 (@itzMikeLucas) March 4, 2022

The idea that a blockchain inscription by a complete unknown could be worth so much money caused widespread cognitive dissonance. Within a week, the term “NFT” leapt from the esoteric realm of specialist discourse straight into the mainstream. As if in reference to Beeple’s title, NFTs became the stuff of everyday. Responses ranged from celebration to lamentation. Digital-art partisans hailed the sale as finally leveling the financial score with painting, sculpture, video, and installation. Optimists deemed NFTs truly democratic: they enabled anyone to produce art easily and cheaply, allowing artists to monetize their work unimpeded by the art world’s established gatekeepers.

More cautious commentators pointed out that such a bombastic auction sale amounted to an expedited strategy to cement the new medium’s bona fides. Beeple had skipped the traditional, time-consuming paths to artistic prominence: being added to museum collections, reviewed in scholarly literature, or curated into important shows. The market’s instant reaction to the auction aligned perfectly with the instant gratification offered by NFTs: conceive/mint/sell, no need to buy paints or order stretcher bars. Meanwhile, the conspiratorially minded insisted that the new artform was but a placeholder for cryptocurrency, a way to turn culture into a financial instrument, and even vice versa.

Still, everyone agreed that art had entered a new era. The tectonic shift seemed as massive as the 20th-century modernist revolution heralded by abstract painting’s challenge to figurative representation. Beeple’s triumph triggered a bonanza in which a handful of people made fistfuls of money. This market euphoria impeded a sober evaluation of the NFT’s aesthetic implications. A year later, however, we may have attained sufficient distance to take a broader perspective on the place of NFTs in the history of modern art. As we do, it is hard to avoid the impression that Tom Wolfe saw something like NFTs approaching over the distant horizon, and that his work predicted their cultural impact with a prescience and perspicuity that deserve wider acknowledgement that it has yet received.

II

As we have written elsewhere, the novelty of NFTs has been much exaggerated. In fact, they are the logical conclusion of a long historical process which was identified almost 50 years ago in Wolfe’s notorious satire of aesthetic modernism, The Painted Word (1974). Wolfe’s extended essay adumbrated modern art’s inexorable drive toward abstraction. It described a revolt against object-based, realist art, which began in the middle of the 19th century and continued throughout the 20th, moving from Cubism through Abstract Expressionism, and culminating in the often entirely abstract genre of Conceptual Art. Wolfe emphasized the continuity of these developments, pointing out that Abstract Expressionism “was a reaction to Modernism itself … an abstraction of an abstraction, a blueprint of the blueprint, a diagram of the diagram.”

During this process, the physical manifestations of an artwork gradually ceded their significance to the abstract theory it exemplified. The New York Times critic Hilton Kramer complained that realism lacked the “crucial” element of “a persuasive theory,” without which he quite literally could not “see a painting.” According to Wolfe, by the 1960s, abstract theories had become the whole point of art: “the paintings and other works exist only to illustrate the text.” In his view, the rise of theory (which took place in literature as well as in the visual arts) was a betrayal of the original, 19th-century modernism, which had largely eschewed theory as a matter of principle. As the painter George Braque declared: “The aim is not to reconstitute an anecdotal fact, but to constitute a pictorial fact.”

Reading The Painted Word nearly five decades after its initial publication is quite a trip. Peter Plagens was not incorrect when he labeled Wolfe’s prose “relentless glib” in his Artforum review. Wolfe admitted as much in 1975, when he appeared on Firing Line with William F. Buckley. He described The Painted Word as “a social comedy” intended to reveal the ways in which cultural mores shape the artistic canon, to expose the mysterious “process by which art becomes serious, by which it becomes praised.” Wolfe’s “social comedy” has now had time to mature into a full-blown tragedy for the kind of art that Plagens and others so valiantly defended 50 years ago. The art world’s evolution since 1975 confirms Wolfe’s claims about the primacy of theories over objects. And his merciless exposé of the socio-economic motives that determine aesthetics is more important than ever in the age of the NFT.

As Wolfe pointed out, the disembodied character of art is a weathered cliché in art theory. As theory grew increasingly influential on practice, it was only a matter of time until the object disappeared altogether from the artwork. By 1968, Lawrence Weiner could contend that an artwork doesn’t “need to be built” in order to exist. And as an old Russian proverb goes, “a holy place is never empty.” The missing object was supplanted by the new importance of the artist’s personality on one hand, and by validation through purchase on the other. Wolfe described how an artist’s image, their “story,” or what Dave Hickey called their “creation narrative,” came to take precedence over their work.

The emergence of NFTs brought the financialization of art to a climax. NFTs exist only in theory. An NFT is not a material entity. It comes into being through a financial transaction, in which the purchaser acquires ownership rights to a digital image otherwise available to anyone with an Internet connection. Anyone can view the artwork, but only the buyer of the NFT can own it. The pleasure of ownership is now an aesthetic experience. The blue-chip auction houses fell over themselves in their rush to validate digital art NFTs: these days money talks and walks (and runs) too. An artwork’s total lack of physical existence is evidently no obstacle to its acquisition of financial value.

Back in the distant ’70s, much to the consternation of the critics, curators, and artists of the day, The Painted Word also mentioned the unmentionable: the role of fashion in the fate of fine art. “Art and fashion,” announced Wolfe, “are a two-backed beast today; the artists can yell at fashion, but they can’t move out ahead.” The Painted Word demonstrated the role of fashion in the art world by describing the rolling waves of ever-changing styles that have won the favor of critics and hence the market. Recent examples include Zombie Formalism, Bad Painting, Black Figuration, and the rise of the digital art NFT falls neatly into this continuum. Modernist sects have always formed cliques to cultivate what Wolfe calls their “merry battle spirit,” and today’s artists are no different. Depending on one’s stock of charity, NFT Twitter Spaces and Clubhouse Rooms seem like dull gatherings of bros zealously spreading the blockchain gospel, or like equitable and nurturing environments helping “creatives” to monetize their output. Either way, they reincarnate the cenacles of the 19th-century rive gauche.

And either way, theory dominates practice. Wolfe attacked the curators, critics, and professors who preached the Modernist gospel with religious veneration. He attacked pomposity and pretension by “putting his readers on” á la McLuhan. In the 1970 conversation, McLuhan noted that a comedian’s “put-on” is “an aggression,” “a way of hurting the public,” so that “when a writer picks up his pen, if he has something to say, it’s going to hurt.” Wolfe’s aesthetic treatises were “put-ons” which were bound to hurt. His sardonic tone earned him the appellation “smartass” from Dave Hickey, but it concealed a serious grievance against the creeping inroads of theory, a protest against the rise of the word, and a rearguard action against logocentric dematerialization. A joke, as McLuhan liked to say, always contains a grievance. Wolfe grieved for the object, for representation, and with the rise of the NFT, it begins to appear that he was grieving for art itself.

Time has proven Wolfe right even if he had “no eye,” as Paul Goldberger declared, and even if his aesthetic theories were, as Robert Hughes asserted, “dumbly simple.” His acuity as a social historian allowed him to identify the means by which financial instruments came to penetrate an art world already well lubricated by theory. It is the successfully completed business deal, which has nothing to do with aesthetics as traditionally conceived, that validates the NFT as an artwork. This confirms Wolfe’s observation that the modern public has no role in determining aesthetic value. That power now rests with those who can shell out six- or even nine-figure sums to buy artworks, after which the critics can invent theories to instruct the populace on how to enjoy such unappetizing fare as Everydays, or CryptoPunks, or Bored Apes. “The public,” as Wolfe put it, “are merely tourists, autograph seekers, gawkers, parade watchers, so far as the game of Success in Art is concerned.”

The Painted Word also exposed the mutual self-interest that lay behind the phony war between the bourgeoisie and the bohemians. It mocked the marketing strategy of aesthetic modernists as the “Boho Dance”: an arcane mating ritual in which downtown artists professed to scorn the tastes and mores of the uptown bourgeoisie as a prelude to succumbing (with appropriate protestations of reluctance) to the temptations of fame and finance. Wolfe shrewdly observed that the avant-garde urge to épater la bourgeoisie was confined to the cultural sphere, scrupulously avoiding the economic factors that actually secured class privilege.

A chosen few artists progress from the “Boho Dance” to “The Consummation,” in which they are elected by the culturati to be “exciting, original, important.” These lucky ones are rewarded with “fame, money and beautiful lovers.” The buyers get to launder their money, and cleanse their consciences, by supporting “the arts.” Wolfe describes “the arts” as the new religion of the ruling class, the socially appropriate recipient of philanthropic largesse from aspirants to the “semi-sacred status of Benefactor of the Arts.” Collectors of avant-garde art have always derived cachet from the bohemian associations of their taste, and today there is nothing more avant-garde than an NFT. For many, the NFT is their first-ever purchase of an artwork, and their self-image as connoisseur is included in the price.

An additional bonus for such collectors is that the images represented by most NFTs are drawn from popular culture rather than from the mandarin heritage of abstract painting. Wolfe outlined a parallel phenomenon among the 20th-century bourgeois, who always enjoyed realism, so long as the critics could provide them with a theory proving that it was “(a) new, and (b) not realistic.” Collectors were emboldened to buy the eminently realistic Pop Art by the appearance of a theory explaining that Andy Warhol did not paint cans of soup but depicted “sign systems.” A similarly convenient theory emerged to show that Photo Realism did not consist of painted photographs but constructed “photo systems.” In every corner of the art world, reality disappeared behind a cloud of theory.

III

The Painted Word drew heavy critical fire. Yet rather than retreat or take cover, Wolfe diversified his attack. His essay was but the opening salvo in a series of three theoretical treatises he devoted to the topic of aesthetics. It was followed by a biting critique of modernist architecture, From Bauhaus to Our House (1981), and then by an acerbic indictment of the contemporary novel, “Stalking the Billion-footed Beast” (1989). Wolfe identified an identical process at work in each area. In painting, architecture, and literature alike, the rise of modernism involved a process of abstraction, a retreat from representational art into self-referential, eclectic forms of expression that required an explanatory theory before they could be appreciated, or “seen.”

This debate stretches back to the origins of Modernism. In the 1920s, Modernists ranging from Marxists like Bertolt Brecht to conservatives like T.S. Eliot began to notice that traditional realism was no longer realistic. They saw radical aesthetic techniques like estrangement, discontinuity, polyvocality, and bricolage as more accurate representations of alienated life in the modern metropolis. A deluge of theoretical manifestos proclaimed the autonomy of the symbol, declaring that signs had attained an independent power that demanded acknowledgment in aesthetic practice. The portraits of Picasso, the poetry of Mallarme, and the prose of Joyce all direct attention to the mode of representation rather than to what is represented. In modernity, as McLuhan put it, the medium is the message.

Defenders of realism conceded that subjective experience of metropolitan life was discontinuous and chaotic. But they claimed that the discontinuity and chaos were artificial and illusory products of capitalism’s incessant revolutionizing of custom and tradition. The apparent autonomy of signs was equally false: a chimera produced by the market’s promotion of symbolic exchange-value over substantial use-value. The artist’s task was to uncover the objective unity and coherence that had been obscured by capitalism’s distortion of society and the psyche, and this could only be accomplished by a rigorous realism. Georg Lukács argued that artists should eschew “immediate and surface” appearances and instead show the world “as it really is.”

Realism was thus conceived as a protest against reality. On this basis, Wolfe took up his position in the realist camp. He declared: “By the mid-1960s the conviction was not only that the realistic novel was no longer possible, but that American life itself no longer deserved the term real.” He scorned the anti-bourgeois pretensions of the artistic avant-garde, dealing them a savage blow in “Radical Chic” (1970), a hilariously brutal account of Leonard Bernstein’s fund-raising party for the Black Panthers. Imitating the fly-on-the-wall technique of cinéma vérité, Wolfe uses the conventions of realism to describe utterly surreal events.

The resulting vignette blurs the border between fiction and reality as effectively as anything by Salvador Dali. It opens with Bernstein’s “vision” of a “Negro” rising up out of his grand piano and, at his party for the Panthers, the vision becomes real. Neither the host nor the guests can quite believe their eyes, and Wolfe imagines their interior monologue: “if I wasn’t here to see it….” The final section deals with the New York media’s derisive coverage of the party, which immediately transforms its meaning in the eyes of the participants. Wolfe’s slice-of-life realism turns self-referential: the media’s representation of the party, rather than the party itself, turns out to be the essay’s true subject.

This device has become a staple of postmodern aesthetics. Paul Schrader and Martin Scorsese employ it at the end of Taxi Driver, when newspaper headlines transform Travis Bickle from psychopath to hero. Wolfe has a good claim to have invented this trick, and he used it throughout his career. In his final novel Back to Blood (2004), a policeman of Cuban heritage dramatically prevents an anti-Castro refugee from landing on Miami Beach. He is delighted at the prospect that: “Todo el mundo had watched his heroics on television. ... He is now known throughout greater Miami, wherever the TV digit-rays have reached.” But on returning home the hero is dismayed: “his father and his mother and his grandparents had been watching the whole thing on American TV with the sound muted, and listening to it on WDNR, a Spanish-language radio station that loved to get furious over the sins of the americanos.” This unfortunate combination of media convinces the cop’s family that he is a traitor. The medium is the message.

Wolfe always enjoyed blurring the boundaries between fiction and reality. His early New Journalism used novelistic methods to describe real events; his later novels described fictional events in scrupulously realistic terms. He capped his career with a series of novels that used strict realism to depict the hyper-reality of postmodern America. The HBO series The Wire has been hailed for its searching examination of Baltimore. The city’s education system, media, economy, police and criminal element are all analyzed in realistic detail. Wolfe’s novels pioneered this approach. Three of the four survey a particular city (New York, Atlanta, Miami) from a totalizing perspective, demonstrating the inter-connected whole that underlies the apparent discontinuity of subjective experience.

The Bonfire of the Vanities (1987) concentrates on the convergence between the financialization of the economy and the trivialization of culture in millennial Manhattan. It eschews the flashy formal devices of postmodernism in favor of rich, deep description of figures and phenomena that are clearly recognizable from real life. The plot recounts the downfall of Sherman McCoy, a Wall Street banker who Wolfe designates by the Hegelian term “bondsman.” McCoy trades in “gold-backed bonds”: financial instruments that represent a determinate quantity of physical gold. Such bonds are referential signs, similar in form to the verbal signs with which Wolfe describes them. McCoy has made his fortune by trading in the kind of money whose value is assumed to be real. He is therefore unprepared for the eruption of hyper-reality in either economic or linguistic form.

In economic terms, hyper-reality produces “derivatives”: financial signs that refer only to other financial signs, rather than to any real-world commodity. In linguistic terms, hyper-reality is manifested in differance: Jacques Derrida’s never-ending chain of representation that never comes to rest in extra-linguistic reality. Sherman McCoy is certainly destroyed by a media wildly independent of anything that might be described as “reality.” And yet, the novel is unimpeachably realistic in form. Wolfe surveys the roiling chaos of 20th-century New York City from a detached, objective perspective. He uses realism as the antidote to the hyper-reality of real life.

He does the same in his second novel, A Man in Full (1998). Here McCoy’s role is taken by Charlie Croker, a heavily indebted real estate mogul from Atlanta. When he begins to miss his payments, Croker’s creditors treat him with contempt, and when he protests, he is reminded of the extent to which character is now defined in financial terms: “‘I know exactly who I’m talking to Mr. Croker. … I’m talking to an individual who owes this bank half a million dollars, and six other banks and two insurance companies two hundred and eight-five million more, that’s who I’m talking to.’” In the financialized environment of late-20th-century America, personality is systematically translated into money.

Like his earlier exposure of the art world’s venality, Wolfe’s warning of financialization’s effect on character was not particularly welcome among mainstream critics. Even today, he is not quite respectable. Despite their commercial success, neither his art history nor his fiction have won the acclaim of intellectuals or achieved academic credibility. Yet this only confirms his thesis that postmodern society has set its face firmly against realism of every kind—and even against reality itself. As the ethical and practical drawbacks of hyper-reality grow ever-more evident, Wolfe surely deserves to be recognized among the most pertinent theorists, as well as the most accomplished practitioners, of contemporary aesthetics. The age of the NFT commands his presence.

On February 23rd, 2022, Sotheby’s Punk It! sale was called off less than 30 minutes before the auction was due to begin. A sloppy tweet from the consignor who withdrew the lot reported: “nvm, decided to hodl [sic].” The single lot of 104 CryptoPunks so unceremoniously withdrawn from sale was valued between $20 and $30 million, the highest-asking price for an NFT at auction thus far. Typically, such last-minute cancelations are attributed to lack of interest from the buyers. But the consignor sent another tweet, this time a tandem meme, one part of which read: “Taking punks mainstream by selling on Sothebys [sic].” The other said “Taking punks mainstream by rugging Sothebys [sic].” We have just witnessed a 21st-century, Twitterified version of the old “Boho Dance” An NFT insider “shows his stuff within the circles, coteries, movements, isms … as if he doesn’t care about anything else: as if, in fact, he has a knife in his teeth against the fashionable world uptown.” As Wolfe pointed out long ago, these are the disingenuous protestations of the career coquette. It is, after all, the oldest profession.