Art and Culture

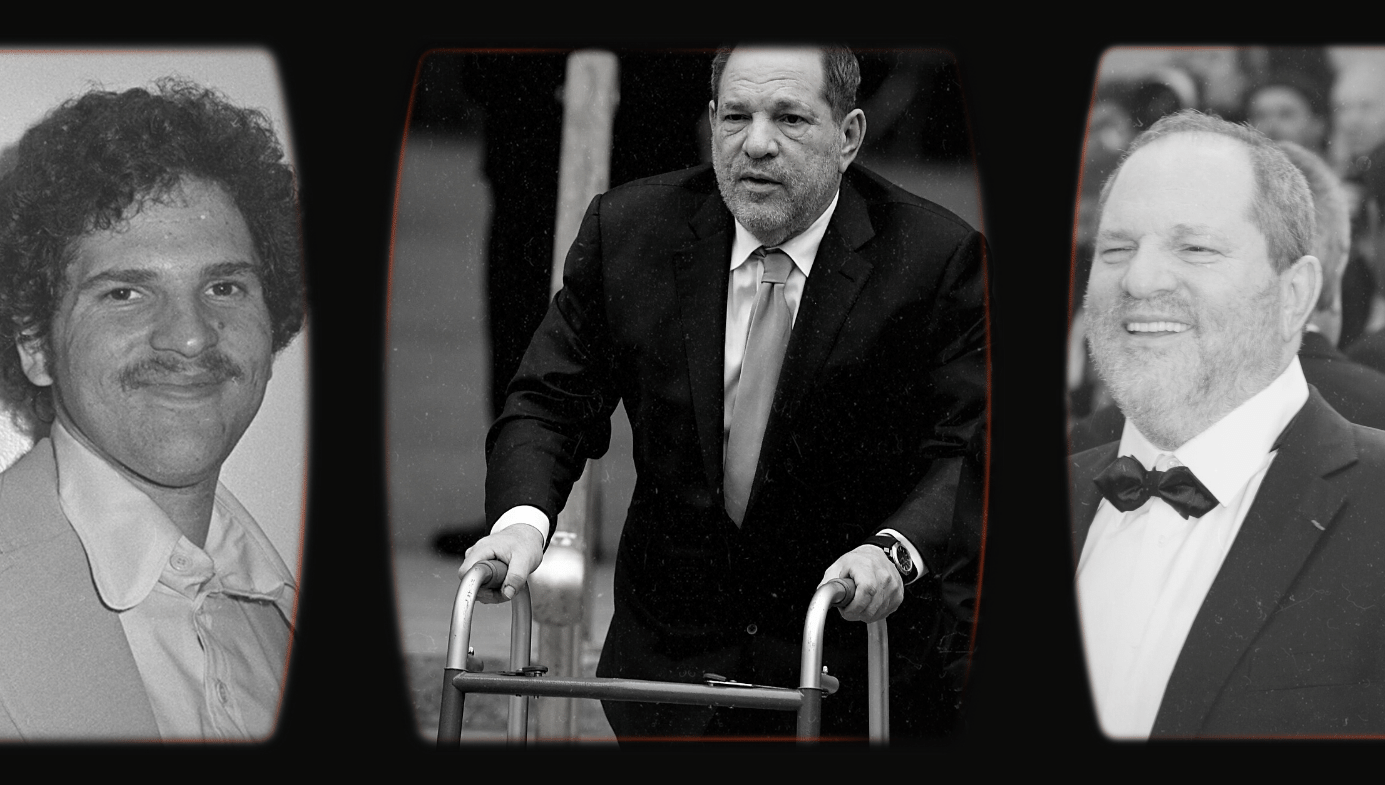

The Transmogrification of Harvey Weinstein

I was a good friend of Harvey Weinstein during his early years as a concert promoter, before he became Harvey Weinstein, movie mogul. We subsequently drifted apart, and while Harvey went on to find astronomic success in Hollywood, I worked as the chief psychologist at the Massachusetts Treatment Center for Sexually Dangerous Persons from 1977–86. I’ve continued to evaluate sex offenders there ever since. The Treatment Center is a maximum-security prison where the most dangerous sex offenders are committed for observation once they have completed their criminal sentences to determine whether or not they can be safely released back into society. If not, an offender will remain incarcerated at the Treatment Center, not infrequently for the rest of his life.

Although the exact number is unknown, fewer than 10 percent of men convicted of sexual misconduct are subsequently deemed “sexually dangerous” and committed for “one-day-to-life.” As reprehensible as Harvey’s behavior has been, it doesn’t approach that of the most monstrous offenders whose crimes led to the creation of statutes that can keep a man locked up for life for crimes he may commit in the future. But before I discuss the problem of male sexual misconduct, let me tell you what the Harvey I knew was like.

I. Young Weinstein

I first met Harvey in 1969, shortly after we arrived as freshmen at the State University of New York at Buffalo. My roommate David was the best friend Harvey ever had, and possibly his only real friend—they had grown up together in the same apartment building in Queens. While they were already starting to grow apart when I met them, we all spent a lot of time together. On one occasion, the three of us, along with Harvey’s brother Bob, took a four-day road-trip from Buffalo to San Francisco just to see if we could do it. We idealized the rebellious beatnik spirit of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, so impulsive excursions like that one were not an infrequent occurrence.

At college, Harvey had become involved in producing rock concerts under the auspices of the Student Union, but he soon realized that he could rent an old under-used theater and hire the talent himself. Around the same time, he stopped attending classes. Once he began to generate income from his concert business, he started to pick up the tab for our adventures. So, on the trip from New York to California, he bought us all tickets to a show in Vegas during which Don Rickles pointed at my long hair and beard and asked the audience, “What have we got here? Jesus Christ?” In California, we saw Bette Midler, who was then a hot new sensation.

One weekend evening after I had moved off-campus, Harvey dropped by the apartment I shared with my girlfriend. Our only toilet was clogged and we couldn’t get it unstuck. It was late at night, so we couldn’t buy a plunger, and we were in the middle of the city during a Buffalo winter, so we couldn’t just go outside and defecate in the woods. What were we going to do? Harvey looked at us with disdain before rolling up his sleeve, sticking his arm into the toilet, and dislodging the blockage with his hand. That may sound disgusting, but the point is not that Harvey was a dirty or unhygienic person. On the contrary, he was always freshly showered and cleanly dressed, if frequently disheveled. But when he saw that something needed doing, he just did it.

Harvey was the quintessential entrepreneur. He had the can-do attitude, the conviction, the drive, and the chutzpah needed for success. When he and David were 11 years old, they had searched the Yellow Pages for bakeries that sold cookies wholesale. They then dressed themselves in Boy Scout uniforms they borrowed from David’s older brother, and went door-to-door selling them for a dollar a box (around $7 in today’s money). This was a lot of money for such young boys and they started taking cabs all over the city, going out to restaurants, and seeing shows. When a skeptical customer asked if they were really raising money for the Boy Scouts, they agreed that phonies were a terrible problem for the Scouts. The man bought two boxes.

But whatever the project, Harvey put his money where his mouth was and then worked his ass off to make it happen. He worked from the moment he awoke to the moment he could work no more and fell asleep. He didn’t eat food; he inhaled it as he worked without breaking stride. But, at that point, his piggishness didn’t yet extend to mistreating people.

In 1970 or ’71, Harvey co-founded Harvey & Corky Productions with Horace “Corky” Berger, a handsome Buffalo local, and somehow managed to get a big music mogul at the Beatles’ Apple Records to become his mentor. Their company was then able to book top talent, and they became one of the Grateful Dead’s favorite promoters. The Dead even had Harvey travel to Boston to promote one of their concerts, which apparently prompted Don Law, the biggest promoter in that town, to remind Harvey of the rules: “I don’t come to Buffalo to do concerts; you don’t come to Boston!”

Not long after that, Harvey produced a Bruce Springsteen concert in a college gym in Niagara Falls, NY. Springsteen had just released his first album, Greetings from Asbury Park, NJ, but he was not yet a superstar, so the huge space wound up with an audience of less than a hundred. That didn’t faze Springsteen, who played his heart out as if the place were packed with adoring fans. After the gig, we had a small impromptu party with the band and crew. Harvey, who always knew where the action was going to be, spent the evening getting to know Springsteen while I just ate the food Harvey had provided. Later, I would be able to say “I ate pizza with The Boss.”

One of the more dramatic stories involved Chuck Berry. Harvey and Corky booked a ’60s revival show that had been touring the country, and Berry was the headline act. But as the warm-up acts were wrapping up, he was still nowhere to be seen. Finally, a nondescript black man in a drab sweater arrived. He told an increasingly frantic Harvey and Corky that he wouldn’t perform unless he received an additional $2,000 in cash ($10,000 in today’s dollars). A near sell-out crowd was getting impatient and the box office had done brisk last-minute business, so there was plenty of cash on hand and Berry knew it. He appeared to have Harvey and Corky by the balls. The three of them went into the office with Corky’s Italian stepfather. When they emerged, Berry quickly got dressed, transforming himself from aging bum into dazzling rock star. The show was a huge success and everyone went home happy. While I don’t know what actually went down in the office, we were later told that Corky’s stepfather had threatened to have his “friends” break Berry’s legs. Harvey was not yet an intimidating fellow in his own right, but he was surely paying attention.

I had quit college (temporarily, as it turned out) in December 1970, after the first semester of my sophomore year. I was becoming more involved with Harvey and drifting apart from David, who had by then joined a religious cult headed by the 15-year-old Guru Maharaj Ji. But I needed a steadier income than Harvey and Corky could provide, so Harvey arranged for his father, Max, a modestly successful serial entrepreneur and skilled diamond cutter, to teach me how to cut high-quality imitation diamonds. Chemists had figured out how to grow a new crystal (yttrium aluminum garnet, aka YAG) that, when cut correctly, makes an imitation diamond so convincing it terrified jewelers. I spent a week as an apprentice in Max’s small factory in New York before returning to Buffalo to cut YAG diamonds with the equipment I purchased from Max. But over the next year, the business started disappearing overseas, and once again, Max had to return to the drawing board while I continued to work with Harvey and Corky in Buffalo.

During my YAG training in New York, Harvey’s parents, Miriam and Max (after whom the brothers would later name Miramax Films) invited me to dinner in their home where I witnessed an eye-opening scene. Miriam, a pretty, petite woman, filled her obese husband’s large plate to overflowing with spaghetti and meatballs. When Max had finished, he pushed the empty plate away and Miriam began insisting that he eat some more. He refused. Several times. He seemed to be aware that he needed to lose weight. But Miriam persisted. Finally, he gave in and ate another vast plateful. Based on this exchange, I assumed that this was a frequent occurrence. I also assumed that Max would die relatively young, which he did a few years later at the age of 51 without ever achieving the success he yearned for.

As Bob later told Vanity Fair:

[M]y father spent most of his life, literally and figuratively grinding out a living to support his family. And, more than anything, Max wanted to be on the ground floor. He wanted to be, as he called it, “one of the big boys,” someone who controlled his own destiny, could call the shots for himself, and had status. Striking it rich wouldn’t have been bad, either. Is it any surprise that one of his favorite songs was “If I Were a Rich Man” from Fiddler on the Roof? As he sang it around the apartment, doing his best Zero Mostel imitation, we would all laugh, and so would he, but underneath it was a serious matter for him. Like a lot of people, he had his dream, but he also had a few plans for achieving it. He was determined to try, and his sons watched it all and learned.

Harvey was determined to achieve the success that had eluded his father, and saw the entrepreneurial struggle as a fact of life. But while he maintained directorial control over any project we undertook, he was also willing to let his ideas be improved by the creative energy of those around him. In fact, he fed off the excitement generated by collaboration. His enthusiasm for our contributions magnified whatever gifts we had, and he made us feel we were helping to turn possibility into reality. It was quite obvious to those who knew him as a young man that he was going to be fabulously successful, wealthy, and powerful. And he was determined to be a force for good—he genuinely wanted the attention he received to be for creating something that brought joy and beauty into the world; he cared about creating excitement; he wanted to entertain.

This was the Vietnam era, when rock concerts were gatherings of young people who believed they were destined to change the world. Instead of just marching in the streets, chanting slogans, and getting tear-gassed (all of which we did), we could use money and organizational power to make a real impact on our troubled planet. So, despite the self-interest inherent in being part of the music scene—making money and interacting with famous and talented people—we were all able to maintain a considerable degree of idealism. Back then, Harvey’s idealism didn’t seem to be in conflict with his egotism. I was proud to help him produce what felt like something important and worthwhile. And like many of those who interacted with him in the years to come, I knew that if I hooked myself to his rising star, I could ride the Harvey Express to the top of Mount Success.

Unfortunately, like the Keseystoned Cops in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (another of our guiding texts), you were “either on the bus or off the bus.” There was a price to pay for riding the Harvey Express; you had to shelve your own agenda and be available to him. And you had to deal with Harvey, who, although not yet nasty or abusive, could already be quite a handful. Whenever my girlfriend (later my wife) complained that I wasn’t doing my share of household chores, I’d respond, “But I’m dealing with Harvey!” This later became a family joke, but dealing with Harvey really was a job. Thankfully, I managed to get off the bus long before it crashed.

During some psychotherapy as an adolescent, I had developed a passionate interest in understanding human psychology. So, after struggling for a semester to make a living without a college degree, I returned to college. When I received my BA in the summer of 1974, I left Buffalo to get my doctorate at Boston University, and that was the end of my close personal relationship with Harvey Weinstein. But others stayed, and we now know that the compromises required to maintain a relationship with Harvey became greater the more successful he became.

I heard from Harvey just once more during my first year in graduate school. During a frantic phone call, he explained that Aerosmith’s lead singer, Steven Tyler, had canceled a gig at the last minute, claiming that he was injured and couldn’t perform. Harvey didn’t believe him. He knew that Tyler was flying home to Boston and dispatched me to the airport to get him to honor his contract. I met Tyler’s plane and explained that Harvey had asked me to give him a ride home. On the way, Tyler explained that he had injured one of his legendary lips on a wire sticking out of a microphone and that a doctor had advised him not to perform for a while. That seemed possible but also possibly quite bogus; there were no visible signs of any injury. When we arrived at his apartment, I helped him carry in his bags and there seemed to be a party going on inside. Maybe he just had some conflict with Harvey. I didn’t know, and there was certainly nothing I could do about it. So, I simply reported what had happened.

After that, Harvey and I had almost no contact for more than 40 years. I did, however, keep track of his growing fame and fortune, and a few years later, I heard a story from David that suggested Harvey was already changing rather dramatically. Harvey had invited David to lunch at some fancy New York restaurant near the Miramax office. While he was regaling his old friend with stories about the rich and famous—like the one about Robert Redford, who apparently always forgot to bring his wallet to the restaurant—a Miramax employee appeared to deliver a message of some kind. Harvey started screaming at the poor guy, apparently unembarrassed about being an asshole in public. In fact, David thought he was enjoying showing off, and although he was laughing as he told me this story, he was clearly horrified. This was not the person we had known. Before he became successful, Harvey’s interpersonal behavior was more consistent with his liberal politics—generosity toward the underdog and concern for the marginalized. Something was clearly changing.

The only face-to-face encounter I’ve had with Harvey in more than 40 years occurred when I ran into him by accident in 2014. I had accompanied a friend to the world premiere of the Finding Neverland musical at the American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, Massachusetts. There was an announcement that the producer would be in the lobby after the show, but I didn’t know or care who that was. As I was leaving, I saw an old man standing in the lobby surrounded by people, and only then remembered that Miramax had produced the movie on which the musical was based. “Is that Harvey Weinstein?” I asked my friend, who confirmed that it was. So, I went up to him to say hello. Harvey didn’t recognize me either (I was an old man by then, too), but when I told him my name, he immediately smiled and offered me his hand. I’m sure he hadn’t thought about me in decades, but in the ensuing exchange we did share a moment of genuine connection when we asked each other if we’d heard anything from David.

A few days later, I wrote Harvey a letter suggesting that the three of us might get together for old times’ sake. I should confess that I had an ulterior motive—I hoped he might be able to help me get my writing published. He responded by email, saying that he’d love to get together with the two of us, and he asked me to set it up. I contacted David through Facebook to see if anything still remained of our friendship. The response I got, though friendly enough, made it clear there was little left. If I were to orchestrate this reunion, it could only be by deceiving David about my motive, and I wasn’t willing to do that. So, reluctantly, I let the idea drop.

A year or so later, I read a report in the New York Times about Harvey allegedly groping a young woman during a meeting in his office. For Harvey Weinstein, it signaled the beginning of the end.

II. Understanding the transmogrification of Harvey Weinstein

On October 5th, 2017, the Times published a lengthy report about Harvey detailing decades of alleged sexual misbehavior. That opened the floodgates—more than 90 women would subsequently come forward with further accusations of harassment and abuse, and charges were eventually filed in New York and Los Angeles. On February 24th, 2020, Harvey was convicted of criminal sexual assault in the first degree and rape in the third degree, and the following month he was handed a custodial sentence of 23 years. He is now awaiting trial in Los Angeles on further charges of rape and sexual assault.

Attentive readers will have noticed the seeds of Harvey’s later abusive conduct in the generally positive account of our friendship I’ve offered above—the egocentricity, the intemperate outbursts, the transactional approach to all personal and business relationships that precluded close or lasting friendships, and the poorly controlled appetites. While he was likable enough back when I knew him, Harvey was frequently difficult. And while his narcissism was often playful, collaborative, and creative, there were times when his room-filling ego left little oxygen for others. His brother Bob has publicly insisted over the years that he never sought media attention, and did not mind being the lesser-known brother, once joking that there was not “physically room” in the spotlight for both Weinsteins anyway.

Still, notwithstanding the evidence that seems obvious with the benefit of hindsight, back in the early ’70s, I would not have predicted that the young man I knew—hard-working, driven, generous, politically idealistic—would become the monstrous grotesque with whom the public is now familiar. I had lost touch with Harvey before his sexual predation began (in 1978, according to prosecutors), and never worked with him in a professional capacity as my patient, so much of what follows is necessarily speculative. Nevertheless, my years of friendship with Harvey and my experience working with sex offenders may help shed some light on how and why he became who he is today.

After his ignominious record of sexual misconduct was reported in the New York Times in the winter of 2017, Harvey vowed “to learn about myself and conquer my demons.” His statement concluded:

I am going to need a place to channel [my] anger so I’ve decided that I’m going to give the NRA my full attention. I hope Wayne LaPierre will enjoy his retirement party. I’m going to do it at the same place I had my Bar Mitzvah. I’m making a movie about our President, perhaps we can make it a joint retirement party. One year ago, I began organizing a $5 million foundation to give scholarships to women directors at USC. While this might seem coincidental, it has been in the works for a year. It will be named after my mom and I won’t disappoint her.

If Harvey thought this would convince the world that, despite his deplorable behavior, he remained a quixotic romantic, he was forced to think again. Almost everyone who read his statement concluded that his professed commitment to liberal causes and insistence that he respected “all women” were a self-serving sham. But almost five decades of working with sexual predators has taught me that men’s sexual urges can lead them to act in ways that completely undermine and contradict their other powerfully felt values and goals.

Just as Harvey’s liberal politics were indisputably sincere when I knew him, his later protestations that he held women in high esteem likely felt true to him in at least one regard. “When you were incontestably the favorite child of your mother,” wrote Sigmund Freud, “you keep during your lifetime this victor feeling, you keep feeling sure of success.” This was certainly true of Harvey, who adored and idolized his mother. Miriam was a force of nature, and the year before she died, both brothers independently told her about their estrangement; they immediately began speaking again—a testament to how much they wanted to please her.

I know it’s hard to understand how someone could act so grossly in pursuit of sexual gratification and still maintain a sense of himself as a man with a profound reverence for feminine power and ability. But Freud noted that it is not unusual for men to have split images of women: the chaste, idealized maternal figure versus the enticing slut. In psychoanalytic circles, this came to be known as the Madonna-whore complex, and it can lead to an apparently irreconcilable split in the way a man treats different women. In an interview with Vogue, Georgina Chapman, who married Harvey in 2007 and left him in 2017 after she learned of his sexual misconduct, explained what had attracted her to him:

He’s charismatic. He’s an incredibly bright, very learned man. And very charitable. He paid for a friend of mine’s mother, who had breast cancer, to go to a top doctor. He was amazing like that. He is amazing like that. That is the tough part of this ... this black-and-white thing ... life isn’t like that. … He was a wonderful partner to me. He was a friend and a confidant and a supporter. Yes, he’s a big personality. And ... but ... I don’t know. I wish I had the answers. But I don’t.

People wonder how Chapman could have been oblivious to the obvious. But the truth may be that the Harvey she knew was simply the Harvey his mother knew—polite, attentive, respectful, devoted, and loving. Apparently, Harvey retained the ability to charm that I remembered. And Harvey could be extremely charming when he put his mind to it. But this adoration can—and often does—coexist with a belief that other women are simply sexual objects to be desired and used; a view that accorded with Harvey’s transactional view of human relationships more generally.

Unfortunately, we can’t deny that this is an ugly but common part of male sexuality. About 65 years ago, Massachusetts created the law that defines a “sexually dangerous person” and set up the special conditions for their custody and treatment for "one-day-to-life." Though the law does not mention the sex of such individuals, there have been well over 1,000 men adjudicated “sexually dangerous” and not a single woman.

Men and women are fundamentally different when it comes to sex. Humans are the only species in which it has been established that females have orgasms at all. Male orgasms, on the other hand, are universal. From an evolutionary perspective, the reason for this ought to be obvious: If the male doesn’t orgasm during copulation, there will be no offspring. And since the female orgasm is not essential to reproduction, it’s not surprising that natural selection didn’t ensure that females are as preoccupied as males with orgasmic sex. Those males most preoccupied by sexual desire tended to optimize their reproductive success and have, therefore, left more copies of their genes behind. They are our ancestors; our genes are the surviving copies of their genes. The genes of less sexually preoccupied males have largely disappeared from the human gene pool.

Natural selection has provided males with two main strategies for maximizing their reproductive success. The first is, whenever reasonably possible, to engage in sexual intercourse with any female capable of producing healthy children. This generally means young and attractive females since, throughout the animal kingdom, those characteristics are typically associated with fertility and vigor. But natural selection does not operate like an intelligently designed machine, and can sometimes produce maladaptive behaviors. A byproduct of the yearning for orgasmic experience is a wide and sometimes bizarre range of sexual predilections, one of which is a fixation on the “whore” side of Freud’s Madonna-whore complex.

But another important male strategy for achieving reproductive success is to fall in love with, court, and commit to a particular woman, to share an exclusive sexual bond with her and nurture the offspring produced. This strategy minimizes the possibility of cuckoldry, thereby maximizing the odds that the children a man raises will be his own. Throughout human history, the male’s continued investment in his offspring greatly increases the odds that they will live to reach maturity as sexually reproductive beings and, therefore, that his genes will remain in the gene pool for future generations. This is the “Madonna” side of the Madonna-whore complex—the side of Harvey that his wife probably knew.

Back when I knew him, Harvey was exceedingly confident in business matters—rather over-confident, it seemed to me at the time, for a young schlub from the big city. But this self-assurance did not extend to the sexual sphere. Though he was likable as a young man, he was not very physically attractive, and on sexual matters, he was astonishingly inexperienced and naive. On one occasion, a bunch of us were sitting around chatting and joking when the topic of masturbation came up. To our amazement, Harvey didn’t know what the word meant. When we explained it to him, he was shocked to discover that we all did it. So, I explained how masturbation works and encouraged him to give it a try—which, as we all now know, he did. We never spoke about it again.

His sexual diffidence, his self-consciousness about his looks, and his general lack of experience may have encouraged Harvey to treat women with the contempt he felt that they had once directed at him. In a 2017 article for the New York Times, Heather Murphy recalled that Dr. Neil Malamuth, a psychologist who has been studying male sexual aggression for decades, had:

…noticed that repeat offenders often tell similar stories of rejection in high school and of looking on as “jocks and the football players got all the attractive women.” As these once-unpopular, often narcissistic men become more successful, he suspects that “getting back at these women … seems to have become a source of arousal.”

I do not know the extent to which such a dynamic fueled Harvey’s later sexual behavior. But I do know that, without the constant gratification derived from the attention of others or the feeling that they are involved in something of profound significance, narcissistic personalities can fall apart. When they are not the center of attention or engaged in an exciting project or attending an important social event, they can become intolerably anxious. That is probably why Harvey worked so hard and was so monomaniacally focused on whatever creative project he was pursuing. Work provided relief from his insecurities. It was inactivity that he found unbearable.

In this respect, narcissistic men behave like addicts, driven by the need to escape an unendurable emptiness, shame, or a defective sense of self. They require emotional soothing or distraction to the degree that their life has otherwise become unbearable. Harvey’s success enabled him to gratify a desire to socialize with famous people and to make donations to politicians he admired, who then befriended him and welcomed him into their circles of power. But he also needed constant stimulation to ward off anxiety. As a young man, Harvey actually tolerated that anxiety reasonably well. It was only when power gave him access to a steadier stream of excitement that he became an addict. That’s when he started hunting for women he could use in masturbatory sexual acts that replaced anxiety with sexual pleasure, after which he could inhale some dinner, go to sleep, and, like Jackson Browne’s Pretender, “get it up and do it again.”

By the time he achieved wealth and status, and the power that came with them, Harvey was in a position to sate himself and he did so. In this respect, he was not especially unusual. The lines of obese patrons at the McDonald’s counter offer prima facie evidence of the fact that many people become pathologically self-indulgent when provided with the opportunity to do so. More than 40 percent of adult Americans are obese, and the Harvard School of Public Health predicts that the number will rise to more than 50 percent in less than 10 years!

Of course, not everyone falls victim to self-indulgent and self-destructive behaviors. But a significant segment of the population does, and for Harvey, sexual self-indulgence became increasingly available as he found himself surrounded by people willing to compromise themselves in order to please him. Aspiring actresses looked to Harvey for opportunities, and were eager to respond to his invitations even though some had been warned or heard rumors of his sexual predilections. From Harvey’s transactional perspective, what he wanted was often no more than a private performance to which he could masturbate. Eventually, he appears to have concluded that he was entitled to self-gratification whenever he interacted with an attractive woman—and he wouldn’t have kept at it for so long if this assumption had never produced the desired response.

Power offered him the kind of protection and perceived immunity that not many men get to enjoy. Although those who knew and worked with Weinstein have vehemently denied knowledge of the full extent of his criminal misconduct, there does seem to be general agreement that his reputation for harassment was well-established in the industry. “There was more to it than just the normal rumors, the normal gossip,” admitted Quentin Tarantino in an interview with the New York Times. “It wasn’t secondhand. I knew he did a couple of these things. I wish I had taken responsibility for what I heard. If I had done the work I should have done then, I would have had to not work with him.” But Tarantino, like many others drawn into Harvey’s orbit, allowed himself to turn a blind eye.

Describing (and defending) his infamous interview with Donald Trump, Billy Bush wrote in the New York Times that:

The key to succeeding in my line of work was establishing a strong rapport with celebrities. I did that, and was rewarded for it … With Mr. Trump’s outsized viewership back in 2005, everybody … had to stroke the ego of the big cash cow along the way to higher earnings. None of us were guilty of knowingly enabling our future president. But all of us were guilty of sacrificing a bit of ourselves in the name of success.

Negotiating a relationship with Harvey Weinstein was much the same. Powerful people were willing to make deals with him, and anyone who wanted power was eager for a chance to ride the Harvey Express. Some of them made moral compromises because the promised rewards of glamor, success, and excitement were too alluring to resist. But success in dealings with Harvey meant getting off the bus in time. Even his own brother (who dawdled too long) eventually figured that out. Utility was the key. People were drawn by the siren song of possibility and by the chance to be part of something that felt intensely alive and significant. Personal ethics were simply collateral damage.

III. #MeToo and the path to redemption

When I read about the groping allegation in March 2015, I felt I had something to offer Harvey—something he might need. I have neither the power nor the desire to help sex offenders avoid the consequences of their actions, so I couldn’t get Harvey out of whatever mess he had created. But if he faced criminal prosecution for a sex crime, he would have to deal with a highly traumatic situation involving myriad dangers that few people (including his high-priced lawyers) understand. And, as was typically the case with Harvey, I again had an ulterior motive. Even if I just offered him a free consultation as a friend, a big case like his could catapult me into the stratosphere of experts who make more than $500 an hour (almost as much as the median income of an NFL player).

So, I contacted Harvey and told him about the expertise I’d developed in the years since he knew me, and offered him a consultation. He emailed back saying that he would call me. But in the end, Cyrus Vance, the Manhattan DA, did not file charges (a decision he may have come to regret), and Harvey never got back in touch. I repeated my offer when the Times published its blockbuster expose in October 2017, and this time Harvey called me back. During the course of our brief conversation, he asked me to write a letter to the board of The Weinstein Company in support of his campaign not to be fired. He was seeking a leave of absence that would allow him to return, and wanted me to advise that firing him could produce an emotional breakdown and psychological damage, for which the board could then be held responsible.

I told him I couldn’t do that; it’s not something a clinician can or should do. After a minute or two, he said he had to make other calls. As it turned out, this was the day he was actually fired and he was still frantically trying to drum up the support he hoped could prevent the inevitable. I told him I’d write a draft of a letter outlining what I could say if I more fully understood what was happening, if he actually decided to enter treatment, if he were willing to face what he had done, and if he really wanted to try to turn his life around. He told me to send it over.

I quickly wrote a one-page letter, emailed it to him, and he responded by asking me to somehow make it confidential and send it to his attorney. I reiterated that what I’d written was just an example of what I might be able to say if the conditions I'd outlined were met. I had no idea if he wanted to take that path. In any case, he wasn’t my patient, we had no professional relationship, and I hadn’t been hired by his attorney to produce a privileged, attorney-client work product. Before I could find out if he was willing to assume responsibility for the mess he’d created, and before his attorney could clarify how a letter from me could be made confidential, it was too late.

Even if our conversation that day had continued, I would have had to caution him that the world did (and does) not seem ready to allow him any forgiveness, so there might, in fact, be no path to redemption available to him. He could take responsibility for his crimes and misbehavior, express remorse, commit to changing his ways, and yet still emerge from the process a despised pariah. Donald Trump clearly understands this, as he noted during a discussion with journalist Michael Wolff about Chairman of CBS, Leslie Moonves:

Les admitted to a kiss. … Forget about it. When I heard about the kiss, I thought, “Done. Finished.” The only person who survived this stuff is me. I knew you couldn’t admit to anything. Try to explain? Dead. Apologize? Dead. If you admit to even knowing a broad, dead.

With the prospect of legal action and personal disgrace looming, Harvey was faced with a similar dilemma. Fight and deny, perchance to thrive and live free like Trump, or repent and try to reform, secure in the knowledge that doing so would finish him once and for all. In the end, Harvey tried a little from column A and a little from column B and was stripped of both his dignity and his freedom.

This zero-tolerance approach to sexual abuse—the demand that society foreclose the possibility of rehabilitation and forgiveness—has only been fortified by the #MeToo movement that exploded in the wake of Harvey’s exposure and subsequent arrest. It is now difficult even to acknowledge distinctions between degrees of sexual misconduct. The fact that incidents of harassment at the mild end of the spectrum can sometimes cause a victim significant distress doesn’t mean that we should treat all sexual offenses the way we treat violent rapes. We accept different kinds of legal punishment for different types of killing (ranging from unavoidable accident, negligence, heat-of-passion manslaughter, all the way to premeditated murder), even though, in the end, all the victims are dead.

Outside of the United States, the problem and the #MeToo response were perceived in a more nuanced fashion. In 2018, a letter signed by Catherine Deneuve and more than 100 Frenchwomen in the entertainment, publishing, and academic fields was published in Le Monde. The authors stated that:

Rape is a crime. But insistent or clumsy flirting is not a crime ... As a result of the Weinstein affair, there has been a legitimate realization of the sexual violence women experience. … It was necessary. But now this liberation of speech has been turned on its head ... men [are] prevented from practicing their profession as punishment, forced to resign, etc., while the only thing they did wrong was touching a knee, trying to steal a kiss, or speaking about “intimate” things at a work dinner, or sending messages with sexual connotations to a woman whose feelings were not mutual.

Yet in the US, we can’t seem to have a rational discussion about relative egregiousness when we’re talking about sex offenders. Discussing the Weinstein case in a 2017 interview on ABC News, Matt Damon provoked outrage when he made this rather banal point. He went on to note that if a man denies any wrongdoing, he may remain at liberty to continue his offensive behavior, so long as he is able to cover it up using lawyers, NDAs, intimidation, and payoffs. If, on the other hand, he accepts responsibility for his shameful conduct, expresses remorse, and takes genuine steps to change, he simply assures his status a pariah. Having acknowledged that an appropriate response to serious criminal offending is often prison, Damon went on to express the need to create a path to redemption for those who wish to take it. Because we now lack such alternatives, he said, we only incentivize denial. Although he subsequently apologized for his remarks, he was right.

My own professional knowledge, research, and experience in the field has convinced me that this approach is not only counterproductive to the aims of the #MeToo movement, it is also unjustified by the known facts about rape and sexual assault. Contrary to conventional wisdom, of all the criminal offenders typically released after serving a prison sentence, sex offenders have the lowest rate of recidivism. This has been established by a meta-analysis of scientific studies that followed almost 8,000 released sex offenders, and studies conducted by state governments as well as by the United States Department of Justice. All these studies—without exception—have found that, when compared to those convicted of drug offences, property crime, non-sexual violence, and so on, sex offenders are least likely to reoffend.

For example, a 2019 study by Alper and Durose for the US Department of Justice produced the following figures:

A 2012 study of sex offender recidivism in Connecticut found that “The sexual recidivism rates for the 746 sex offenders released in 2005 are much lower than what many in the public have been led to expect or believe. These low re-offense rates appear to contradict a conventional wisdom that sex offenders have very high sexual re-offense rates.” A 2015 Wisconsin study found that “The two core findings pertaining to lower rates of recidivism for sex offenders when compared to the overall offender population and the considerably low sexual recidivism rates have strong empirical support within the research literature.”

So, why does almost everyone believe the opposite? Why is someone like Harvey Weinstein (who isn’t even in the same league of horror as many of the men I’ve seen completely turn their lives around) considered irredeemable? Unfortunately, it is because a lot of misinformation about sex offenders has come to be accepted as fact.

In 1986, an article by Robert Longo in Psychology Today stated (without reference to any supportive data or scientific research) that “Most untreated sex offenders go on to commit more offenses, indeed as many as 80 percent do.” That article was then referenced in a manual published by the US Department of Justice. And, on the basis of that manual, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote in a 2002 SCOTUS decision that sex criminals pose “a frightening and high risk of recidivism” and that “the rate of recidivism of untreated offenders has been estimated to be as high as 80 percent.” Justice Kennedy repeated the “frightening and high” claim in a subsequent decision the following year.

When interviewed about this misunderstanding for a NY Times Op-Doc, Longo pointed out that he had been writing before research had established the likely rate of sex offender recidivism, and that estimates ranged widely. “I’m appalled that this could happen,” he said. “This was not my intent, not my intent at all.” In the same video, the author of the DOJ manual quoted by Justice Kennedy, Dr. Barbara Schwartz (who later became the clinical director of the same facility where I had been the chief psychologist), stated:

In 1988, I was given an assignment by my employer to research sex offender programs around the country. I couldn’t find any. So, basically, I just made up a model. [That manual] had six references including the dictionary and the paper that Rob Longo did for Psychology Today. The best we were doing was just making a bunch of guesses...

A subsequent DOJ study followed 272,000 criminal offenders (including almost 10,000 sex offenders) who had been released across the country in 1994, and looked at data from several later studies. Its authors determined that the three-year post-release recidivism rate for sex offenders is (1) about five percent and (2) far below the recidivism rate for other types of offenders. And, if a sex offender has been out in the community offense-free for 10 years, the likelihood that he will be arrested for a new sex offense shrinks to less than one-in-a-hundred—the same ballpark as a man who has never been accused of a sex offense before.

But once SCOTUS had officially declared that sex offenders reoffend at a frighteningly high rate, politicians clambered over one another to announce that they were best-placed to protect us from this menace. If a challenger could claim, in the wake of a high-profile case, to be harder on sex offenders than an incumbent, the incumbent would likely lose the election. And the media (all forms of which are locked into an increasingly desperate struggle for market share) duly joins the outrage-and-blame frenzy whenever a released sex offender commits a new offense.

Certainly, there are some truly horrific, compulsive, and monstrous sex offenders. I’ve dealt with quite a few during the course of my career. And such men should be held indefinitely or until there is reason to believe that they are no longer dangerous, even if that means imprisonment for life. But such offenders are far rarer than one would assume from the frequency with which they are hyped in the news in a country of 330 million people. Our hysterical overreaction results in a mismanagement of the problem of sexual abuse and an enormous waste of resources that actually make us less safe.

When I was a youngster, a person was far more likely to be attacked by a violent criminal, including a sex offender, than they are today. And yet, today everyone feels more unsafe. Online registries inform us that “high risk” sex offenders live all around us. That simply isn’t true, but who is going to (accurately) rate the vast majority of sex offenders as low risk? If a sex offender so rated were to reoffend, the registrar would be fired and the politician who appointed him would almost certainly be kicked out of office. So, the only politically prudent solution is to rate almost all sex offenders “highly dangerous.”

This kind of fear-mongering produces other unpleasant side effects. As Leo Carroll, a professor of criminology and criminal justice at the University of Rhode Island, has noted:

Because they are based on myths, laws requiring community notification and restricting residency [of sex offenders] do nothing to ensure public safety and may in fact be counterproductive. Stigmatizing and isolating offenders may lead many of them to adopt a transient lifestyle that eludes monitoring and deprives them of support and treatment.

One study has found that housing prices in the vicinity of a registered sex offender fell by between four and 12 percent, and another reported that the time it took to sell increased by 84 percent. So, the innocents in an offender’s neighborhood (whom registration is meant to protect) are not only made increasingly fearful, they are also punished financially. And even though most sex offenders’ family members are completely blameless, it has been reported that as many as 44 percent of an offender’s cohabitants have been harassed, threatened, attacked, or had their property damaged as a result of registration.

While I believe the public is entitled to information about truly dangerous offenders (sexual or otherwise), politically run registries make it impossible to formulate either a truthful understanding or a rational response to the problem. According to Kate Hynes at the Dickinson School of Law:

...large registration systems can be nearly impossible for law enforcement to monitor effectively. A police captain in Georgia noted that he needed four police officers working full-time just to monitor the sex offender database in one county. As the number of sex offenders on a registry increases, it becomes more difficult for both police and civilians to distinguish between low-risk and truly dangerous offenders.

If we, as individuals and as a society, were able to have an honest discussion, we might be able to redirect the energy and money wasted on draconian prison sentencing, lifelong commitments, and lifetime registration for many men who are, in fact, not dangerous. If, on the other hand, we continue to believe that all those who engage in sexual misconduct are irredeemable, we will feel justified in concluding that rehabilitation efforts are pointless, even though the scientific evidence plainly demonstrates that the vast majority of sex offenders are corrigible. A refusal to accept the possibility of reform or to distinguish between degrees of criminal gravity means that we’ll have to incarcerate and/or shun an enormous percentage of the male population. After all, isn’t the fact that sexual misconduct is so common what the #MeToo furor is all about?

We now inhabit a Schizo-PC world. On one hand, women are encouraged to make themselves as attractive as possible. On the other, we find it crude and even criminally offensive when men openly acknowledge their ubiquitous and often overwhelming sexual arousal. In order to create a path to redemption for sex offenders, we must acknowledge that male sexual misconduct is a terrible and common problem. In such a culture, we could help adolescent boys to acknowledge the extent of their desires and to distinguish between what they desire and what is acceptable. In the current climate, however, a young man would be insane to openly discuss the full extent of his desires.

If you read the nonsense written about sex offenders, sooner or later you’ll encounter the claim that rape and sexual abuse are about power, not sex. It is certainly true that sex offenders often employ violence, intimidation, and/or authority to coerce and manipulate their victims into compliance. It is also true that, for the victim, the experience of sexual abuse is about power—or rather, powerlessness. For rape victims, the experience may range from appalling disgust to abject terror, neither of which could be called a sexual experience.

Nevertheless, for the vast majority of offenders, the goal is sexual gratification, and they would not employ force if they could obtain consent. As the Monster put it in Mel Brooks’s 1974 comedy, Young Frankenstein:

For as long as I can remember people have ... looked at my face and my body and they ran away in horror. In my loneliness I decided that if I could not inspire love, which is my deepest hope, I would instead cause fear.

With the exception of sexual sadists, a very rare minority of offenders for whom arousal is contingent upon their victim’s suffering, what sex offenders really want is to be welcomed, invited, and encouraged by the objects of their sexual desire. Even the vast majority of violent rapists, whose crimes can be quite horrific, wish they could obtain voluntary compliance, because the height of male orgasmic joy is attained not by violent domination but by loving sex.

What the offender gets instead is the consolation prize, which he actively seeks because his intense sexual hunger makes consolation feel better than nothing, at least for a moment. During a rape, when the victim is obviously suffering, the rapist abandons his impossible dream and focuses on the raw pleasure of using the woman as an unloved object for his sexual release. But a surprising number then feel ashamed or guilty and apologize immediately after the act. Others resort to delusional rationalizations (called “cognitive distortions” in the sex offender treatment business), and convince themselves that the victim actually “wanted it,” or that she was teasing him and so “she got what she deserved.”

Am I claiming that Harvey Weinstein and other men convicted of rape and sexual abuse can’t help themselves and so aren’t morally responsible? Hardly. Understanding why someone does something is not to deny their responsibility for doing it. Understanding the underlying causes of behavior does, however, provide us with a way to discuss the problem rationally and create a path toward change. We must find a way to have the same kind of open and honest discussions about sexual abuse that we have about food, alcohol, and drug abuse. The key difference, of course, is that while other addictions can inflict profound collateral damage, the primary victim is the addict. With sexual abuse, however, there is always an unwilling participant—the true victim.

We have to teach children, especially boys, how important it is for them to find some acceptable way to deal with the desires that will dominate their lives from puberty onward. We already tell them what is acceptable, but we give them no forum in which to acknowledge how difficult it is to follow the rules when the urges become overwhelming and they feel like monsters for desiring the same things all men desire but rarely acknowledge openly. We need to be able to discuss the consequences of sexual misconduct and realize that not every inappropriate act or overwhelming desire is an indication of hopeless degeneracy. People can and do learn to control and change their behaviors. We simply need to stop the shaming and secrecy so that people can share strategies for finding meaningful lives in community rather than hiding from one another.

IV. Epilogue

While I was writing this, I came across a video of Harvey being slapped and insulted in a restaurant near the upscale rehab facility he had entered voluntarily. Dazed, disheveled, and obese, Harvey stumbled slightly after he was struck. There was no anger. No outrage or aggression or indignation. The fight had gone out of him. He looked like a broken man.

Based on what I saw in that video, the rehab seemed to be working. The collapse of his egotistical facade is almost certainly necessary if he is to face the ugliness of his behavior, the suffering he caused his victims, and the profound betrayal of his own values—not to mention the shame he had brought upon himself and the family name of which he was so proud. This is the path by which an offender renounces the abhorrent creature he has allowed himself to become.

If you’ve never done anything comparable to what Harvey did, this may be hard to understand. So, let me put it another way. If you are middle-aged or older, you probably look back on some of the things you did in your teens and early 20s with a mixture of horror and wonder. Youthful behaviors that were consistent with who you felt yourself to be at the time will have become totally alien or even appalling to the person you are now. People change. And when they do, the person who did those things no longer exists. That’s how the majority of sex offenders eventually change—they join the rest of us in seeing their criminal behavior as deplorable.

If Harvey could embrace his shame instead of hiding from a world drunk on righteous condemnation, he could help society to face and better understand the enduring problem he has come to personify. In such a scenario, his repentance and reformation could actually contribute something of value, and help to move the conversation about sexual abuse beyond the unending and counterproductive cycle of perpetual rage and vengeful disgust.

But a climate in which that would be possible remains a dream for now. If Harvey’s legal defense—the dogged insistence that all his sexual encounters were consensual—makes him look even more monstrous, it behooves us to acknowledge that we have given him no choice. Our “lock the door and throw away the key” reaction to sex offenders leaves them no option but to deny and hope they can avoid imprisonment. Society’s premature conclusion that Harvey is an incorrigible monster becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy that produces more evidence of his apparent incorrigibility.

In October 2020, I got a message to Harvey in prison through his public relations representative, and he emailed back to say he would call me when he could. I haven’t heard from him since, but from the reports I read in the media, he appears to have hunkered down in survival mode and is still battling to appeal his conviction as he faces a second criminal trial. Harvey’s no fool. He doesn’t need Donald Trump to tell him how the world works.

I got to know Harvey pretty well when we were both young men, and I liked and even admired him. If you’ve noticed that my own self-interest frequently informed my interactions with him, you are sharing part of my understanding of him. He simply didn’t have close or lasting friendships, and the transactional nature of his relationships may have been the mindset from which his abusive sexual encounters arose. People offered themselves to Harvey as he became more powerful, and he devoured them. Some entered the demon’s den unknowingly. Others were forewarned but entered anyway. Either way, numerous people ended up being fed to an ego that could not be sated. In his mushrooming, ravenous grandiosity, Harvey abandoned everything he had at one time held sacred. In the end, his ego’s endless, aching hunger was so all-consuming that it ate itself.

But I maintain that there is a decent spirit, long buried deep inside Harvey Weinstein. Despite all the mortifying revelations about his scandalous and criminal behavior, I can still see, hidden inside the egomaniac he became, the Harvey I considered a friend. His pitiable claims to respect women and his liberal politics may seem like a monstrous front, but I have learned to find the humanity even within monsters who have done far worse than anything of which Harvey has been accused. The boy who wanted to make his parents proud by wowing the world with his creative genius is shriveled, cornered, and hiding in desperation. For his own sake, he needs to shed his armor so that, when the time comes, he can face death with a degree of personal integrity.