Science / Tech

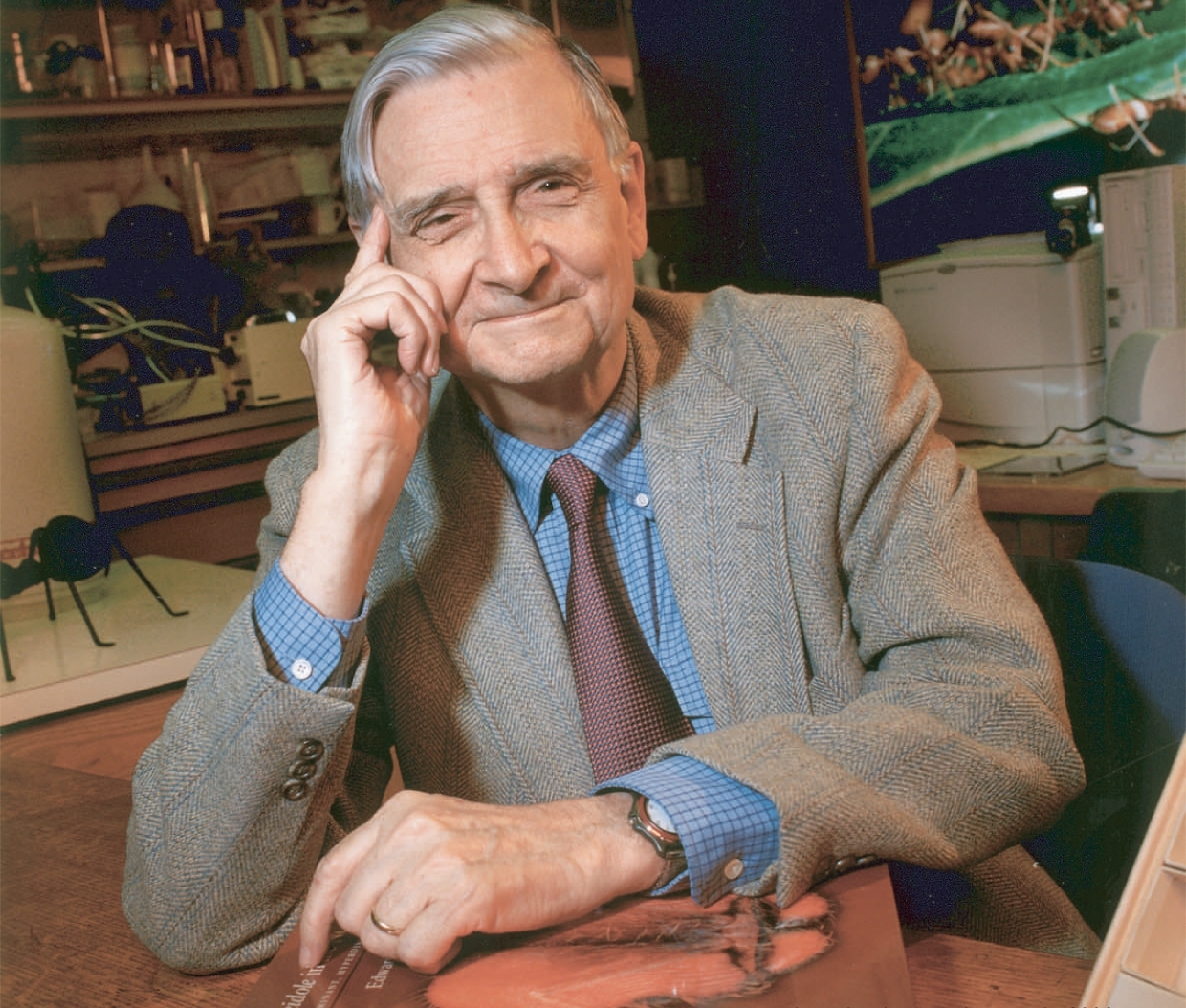

A Conversation with E.O. Wilson (1929–2021)

In fact, at that meeting, InCAR—the International Committee Against Racism—held up signs condemning me and sociobiology and racism in general.

NOTE: The pioneering American biologist Edward O. Wilson passed away on December 26th, aged 92. The following interview was conducted by phone on August 24th, 2009, as part of Alice Dreger’s research for her book Galileo’s Middle Finger. The text has been lightly edited for length and fluency.

Alice Dreger: I know you’ve spoken about it many times before, but I would like to begin by asking you about the session at the 1978 AAAS [American Association for the Advancement of Science] conference during which you were rushed on the stage and a protester emptied a pitcher of water onto your head. By all accounts, the talk you then gave was very measured. How on Earth were you able to remain so calm after being physically assaulted?

Edward O. Wilson: I think I may have been the only scientist in modern times to be physically attacked for an idea. The idea of a biological human nature was abhorrent to the demonstrators and was, in fact, too radical at the time for a lot of people—probably most social scientists and certainly many on the far-Left. They just accepted as dogma the blank-slate view of the human mind—that everything we do and think is due to contingency, rather than based upon instinct like bodily functions and the urge to keep reproducing. These people believe that everything we do is the result of historical accidents, the events of history, the development of personality through experience.

That was firmly believed in 1978 by a wide part of the population, but particularly by the political Left. And it was thought at the time that raising the specter of a biological basis for human behavior was not only wrong, but a justification for war, sexism, and racism. Biological gender differences could justify sexism, and any imputation that we evolved a human nature, or that human qualities might differ from one race to another, was dangerously racist.

So, furious ideologically based opposition had built up in 1978. That opposition had been fanned by a small number of academics including [paleontologist] Stephen Jay Gould and [evolutionary biologist] Richard Lewontin and two or three others on the Harvard faculty who thought this was a very dangerous idea and said so. These people helped organize the so-called “Science for the People” movement, or the branch of it called the “Sociobiology Study Group.” Their purpose was to discredit me personally for having brought up such a dangerous and destructive idea.

In fact, at that meeting, InCAR—the International Committee Against Racism—held up signs condemning me and sociobiology and racism in general. Of course, racism never even entered my thinking in developing these ideas. Anyway, after they dumped the water on me, amazingly, they returned to their seats while I was drying myself off. A couple of people then made short speeches—most notably Stephen Gould, of all people, the guy whose agitation and inflammatory essays had been partly responsible for all this. He addressed the demonstrators and said, in effect, that while he fully understood their motivation, violence was not the right way to achieve their goals.

As for me, I don’t know why, but I just get calm under a lot of stress. I’ve been in that sort of stressful situation many times, especially in the field. I started thinking to myself, this is probably going to be an historical moment, and it is very interesting. I wasn’t in the least doubt that my science was correct. I knew this was a kind of aberration. I understood the source because I knew the people who had been the chief thinkers, the ideological leaders. An astonishingly good percentage of them were on the faculty at Harvard. I wasn’t concerned this would come to anything in the long term.

So, someone found a paper towel and I dried my head. As soon as things settled down, I just read my talk. I knew things were going to work out—there was so much evidence accumulated already for a somewhat programmed human brain. By then, it was already coming from many directions, including genetics and neuroscience. There was no doubt about where things would go. There may be hold-outs but the inevitable conclusion from neuroscience and anthropology and genetics is for this way of thinking. [American anthropologist] Nap[oleon] Chagnon was present and he was certainly a leader in thinking about human nature and how valuable it is, and what its motivations are, by studying groups like the Yanomamö.

I knew history was on my side. I was young enough that I thought I would live through a good part of it. I was annoyed! But I wasn’t under stress in an extreme way. Before going home, I went to the next session, at which an anthropologist made the mistake of stating that I believe every cultural difference has a genetic basis, so that I am a racist. Of course, I rebutted that, but that was the kind of thing being exchanged at that meeting.

AD: When Nap told me the story of the AAAS, he recalled that you had a broken leg?

EOW: Oh, that’s right! I was a runner, and I had slipped on ice and broken my ankle. So, I was hobbling along in a cast. The commotion was mainly due to resistance to the Vietnam War. I think that was the gut issue behind a lot of student demonstrations. Since that occurred during the amazing decade of the civil rights revolution, it all got blended together. So, there was a lot of action like that, of students taking over stages or protesting. That was the context of the event at the AAAS. So, it wasn’t totally surprising.

AD: Napoleon Chagnon has told me that he tried to support you in various ways through the years.

EOW: I admired him enormously and still do. I admire him for his work on the Yanomamö, quite apart from the fact that he picked up on sociobiology almost immediately and started applying some of its thinking to Darwinian fitness. The originality of his work is admirable, and he based it on solid empirical research into the role of vengeance raids, but also the interest in acquiring women. And that became an empirical theme of his research. He studied the genealogy and pedigrees of these people with the help of blood samples. That was very novel and important research. To me, he represented the new anthropology, the new cultural anthropology, which is finally beginning to take hold. Though, as you probably know, there is still a school of thinking that rejects anything to do with biological research of the kind that Chagnon pioneered. He was very admirable in the way he just entered the Yanomamö society during a period of great risk and uncertainty. They really are a violent people. So, I was already an admirer of his before I met him.

In my memoir, you’ll see a photograph from the first meeting of the Human Behavior and Evolution Society. He should be in that photograph. They were the founders of sociobiology. There were about six people in the photo, including Bill Hamilton and others. Nap was already a leader in that movement. What a warrior. He was at that meeting at the AAAS, and as soon as those people took the stage, he tried to rush up and fight them, but he couldn’t make his way up through the melee. I couldn’t help but think of him not only as heroic but also as a real friend.

AD: Chagnon said that, when he was subject to the controversy over [journalist Patrick Tierney’s 2000 book] Darkness in El Dorado, you called regularly to check on him and to offer support. [Tierney falsely accused Chagnon and his colleague, the geneticist James Neel, of conducting unethical fieldwork among the Yanomamö tribe and of exacerbating a measles epidemic in the Amazon Basin.]

EOW: That’s right. We’re talking about 10 years ago now, right?

AD: Yes, just about.

EOW: There was a group that came to Nap’s defense. I was one of them. By that time, I had some prestige, so I could offer some help. I was a member of the National Academy and had the National Medal of Science, and at least one Pulitzer by then. So, I just put those cards on the table to help him. He deserved it and I thought that was the only thing to do. I did it gladly. And there were others like [American anthropologist, John] Tooby and people who helped from evolutionary psychology.

Others were outraged, and threats were being passed on to W.W. Norton for not being more careful and for publishing a clearly libelous book. The tragedy of it was that James Neel—a very established senior scientist, a member of the National Academy of Sciences, a leader in human genetics—was really subject to libelous attack in Tierney’s book. But there was nothing that could be done because he had died. If he had lived, things would have been a lot easier for Nap. They could have brought suit against Tierney and maybe even Norton itself. They could have cleansed the whole thing in public. But Neel was gone. I learned to my shock that libel suits cannot be conducted by the family of the person libeled. That’s amazing, isn’t it? The family was kind of helpless because they didn’t have the public voice or the weight.

We made one hell of a fuss. We really did. I wrote a very pointed letter to the president of Norton, [W. Drake] McFeely, and we had an exchange about this. There wasn’t much he could do but say we did all this in good faith. He didn’t say the book was wrong or anything. He didn’t want to get into anything in print that would allow a breach to be formed for a later libel suit. It died down.

Nap, who I thought normally would have gone after them with ferocity, had sort of seemed to lose his spirit at that time. But I was certain he was not guilty of the misdemeanors or crimes Tierney had accused him of. He and I had long talks about this for a time. There was a strong response from part of the community that owed it to Nap, but on the other hand, Nap did not immediately do what we all wanted him to do, and write a true story of what had happened during his studies with James Neel. He had written books describing his adventures, but he really needed to write a book that described just what was being done and what all the work was about. You could get that from the technical papers and his earlier books, but it wasn’t in a form that could serve as a rebuttal to the Tierney book. It was a surprise that Nap didn’t publish something within a year or two. But he let it slide for reasons maybe you understand better than I do. I didn’t keep up too much with him after this.

AD: Nap is finishing up his memoir, but I’m not sure he is going to situate his story in that larger context, of what happens in cases like that.

EOW: I’m glad you’re working on this. It all needs to be put it in a larger context. That would be a wonderful thing to do. I don’t know if you want to come right up to the Bush administration and the Evangelical advances, the know-nothings’ attacks on science. We have to decide what to do in these situations. I chose to write The Creation. In that book, I set out not to confound the fundamentalists—that’s been done a thousand times, virtually without effect—but rather to call on them for help. That had far more effect on Evangelicals than a hundred volumes by someone like Richard Dawkins condemning religion. I just brushed that aside, said I was a secular humanist, and began with a letter to an imaginary pastor. I said we are not going to save life on Earth unless science and religion can work together.

AD: One of the things I really admire about your work is how you try to be constructive. I think that is so much more effective than mere criticism—you work on really moving people to act, to go beyond long-term divisions to ask how we can get somewhere.

EOW: I think that work has been very productive. It helped move Evangelicals more decisively into conservation. Once they see what they call “the Left,” the environmentalists and the scientists—what Rush Limbaugh, that expert on climate change, has called “the granola-crunching tree-huggers”—are not necessarily the dangerous threat they thought, they are not as aggressive. I understand Evangelicals well. They circle the wagons, but they are afraid of all these happenings. Once they see they could form a non-threatening alliance for a transcendent purpose, then they could move forward. That’s why I wrote the book. You have 42 percent of the American people who might be rallied for the environment, particularly for conservation. So, that’s made a lot of progress. I was invited to a meeting with the heads of the Mormon Church, and we met at the president’s office.

AD: Is that why you were recently in Utah?

EOW: I was there to give a talk at the Natural History Museum, and the elders invited me over for a meeting and it worked out awfully well. I had a meeting with the principal bishop the next day. Wonderful things can be done if you give people a reason to come together. You know, if one of those protesters, especially the young woman who dumped the water on my head, were ever to come forward and say, “I’m sorry we were so violent about that,” I would take them to dinner. I would enjoy talking to them today. That’s the way out.

However, the attack on Nap Chagnon was different. That may have been motivated by pure ideology—maybe Tierney felt he could strike a blow for his ideology by tearing down someone like Chagnon. But I have the impression he was an opportunist who saw a way to get famous and make money.

AD: I think to some extent, Tierney was an opportunist of that sort. But I think he was also a zealot, someone who saw himself as a kind of savior to marginalized people—someone who could save the world, so to speak. I think this is not that different, probably, from the way Gould saw himself. It is ultimately a self-defeating approach—to be so committed that you stop looking beyond what you already believe.

EOW: Ultimately it was self-defeating for Gould. Maybe for Dick Lewontin, too.

AD: And I think, too, that Gould saw it as a route to being well-known and beloved.

EOW: What you said about Gould was correct. But I knew him well enough to know he sought fame and riches. He sought that out. That’s an interesting subject in his own right. I would love to read about Tierney’s background.

AD: He is an interesting character. I located and read a book manuscript he never published, a sort of memoir, and it reveals a lot about his allegiances. He certainly saw himself as a good Catholic boy, and so he positioned himself against sociobiology, by which he meant, bizarrely, any explanation of human behavior that saw sex drive as a motivation.

EOW: It sounds as though it is coming from the Right. At least a highly conservative view on biology.

AD: I’m not sure if those missionaries would be correctly classified as being on the Right. They are in some ways on the Left in terms of their focus on the poor and disenfranchised. It’s hard to say, except that they all saw themselves as saving the poor Indians.

EOW: These religious orders have been doing this for centuries, with the help of the Spanish soldiers, they gathered up all the libraries of the Mayans and burned them. Now we only have about four codices left.

This is one of the real stresses and strains of a democratic society. It is frightening that this sort of thing can happen in America. We have come through some scares since the Second World War that should have been warning signs. You could excuse anything until the Second World War, even the confinement of Japanese Americans. This was not a sign of a national trend getting worse. This was an emergency response that was wrong. But by the time of McCarthy, and I remember him well, it got scary. Fortunately, that collapsed finally, but we’ve had one movement after another since the ’60s. We’ve had tighter connections, it appears to me, with specific ideologies or religions, and that to me is a more profound and dangerous trend, if it is continuing. Do you think that what happened in the ’60s and then the aftershocks in the ’70s—the conflicts over civil rights, ideological movements, some ideological extremism on the Left—was temporary? Have people come around?

AD: Well, extreme leftism does seem to have become embedded in academia.

EOW: Yes, it has been. In fact, I’m glad you mentioned that. I’ve often said that the only place certain subjects are completely taboo is the university. In other words, you simply don’t bring up race anymore. You don’t bring up gender differences anymore except very gingerly in a roundabout way. And so, here at Harvard, we got rid of President [Larry] Summers, based on his slip about gender differences in physics abilities. I don’t want overstate it, but it is true that far-leftist ideology has been pretty well embedded.

AD: It seems very easy in the Internet age to have someone like Tierney, who is basically a nobody, effect a take-over of someone’s professional identity. What he was able to do to Neel and Chagnon is very disturbing.

EOW: Yes, Nap Chagnon got tarred by this takeover of identities, and there was almost no way he could defend himself—it was far-off in Yanomamö-land, and people were just willing to accept the demonic image. It wasn’t Ypsilanti, Michigan, you know—a place Americans had heard of. So, they could just believe all the things said about what went on there. But even before the Internet, there were colleagues I’ve had to watch closely, out of self-defense. Gould and Lewontin could change your identity to evil. Until the end, Gould was continuing to speak out against studies on human genetics and the biological basis of human behavior. At every opportunity, he would put the needle in.

AD: Gould and Lewontin were able to do this because they were so well-known and beloved by the Left that they had lots of opportunities to publish quickly and prominently. So, they were able to do the kinds of things that later became possible for more obscure people to do via the Internet.

EOW: That’s right—Gould and Lewontin could publish fast and easily. In the early days of forensic DNA analysis, Lewontin came out with a tremendous blast against it and, to my astonishment, he actually had a paper published in Science. He said that since the odds of making a mistake with an African American was greater than making a mistake with whites, forensic DNA analysis was racist and should not be used. He was talking about how the chances of making a false match by chance alone was one in, say, 150 million (I’m just making up numbers here to illustrate his point) in African Americans, while in whites it was something like one in 300 million, so we shouldn’t use the technology. Of course, soon afterwards we saw not people being unjustly convicted, but people being freed when their convictions were overturned, many of whom were African Americans who had been wrongly convicted! I use that as an example of how it is possible for a few individuals like Tierney or Lewontin to do a lot of damage. Lewontin’s forensic DNA paper was quickly forgotten. But in the case of Nap Chagnon, you had a reputation destroyed, or close to being destroyed.

AD: Well, in many ways, Tierney was aided and abetted by the American Anthropological Association. The AAA convened the El Dorado Task Force which ended up investigating many of Tierney’s allegations, without investigating Tierney. Nap experienced that as a kind of special persecution.

EOW: I had forgotten that aspect of it. That’s true. The AAA was picking up and amplifying the whole thing. The AAA held a meeting around ’76, and I was invited to give a talk on sociobiology. It was proposed that sociobiology and the whole field be condemned by the AAA. Margaret Mead spoke up and effectively said, “Are you out of your minds?” and the move to vote to condemn sociobiology failed. I remember Nap and several others excitedly meeting me as I came in, saying, “Well, that was a narrow escape!” The AAA really played a villainous role in the case of Nap. I wonder if that would be the case today.

AD: I rather doubt it. A lot of the anthropologists I’ve spoken to feel the entire thing was badly handled. They are embarrassed about the AAA’s handling of the matter, particularly with regard to convening the Task Force.

EOW: That’s another scandal—the Task Force. It’s shameful. This is coming out of academia. You know, if we’d had honest biology, somehow rigorously held to as a science, we’d probably—this is an impossible scenario, of course—we would somehow not have had the pseudo-racism and the murderous ideology of the Nazis. Suppose that had been the case, if biology had been protected as a science. But it was not, and not in this country either.

That is something that the radical Left, including home-grown Stalinist sympathizers, rarely thought about. Of course, there were not many left by my time. But the Khmer Rouge had this notion of the far-Left—which was picked up by the leaders, I’m told, in Paris—that the human mind could be molded to anything to fit the perfect system. What you had to do in Cambodia, then, was bust people out of the “evil” cities and put them in communes and get rid of all those who had been programmed the “wrong way” to get a new paradise. So, on the one extreme, you have the idea of the racial purity idea of an Aryan people, that it’s all about biology. And on the other extreme, an idea of the cultural purity of a radical reforming society. Those are the two extremes, and a lot of people suffered because of them. They were both based on poor science. I guess there are echoes or aftershocks of those ways of thinking, still.

AD: I want to ask you about something related to that. Obviously both the Nazis and the Khmer Rouge suffered from the naturalistic fallacy. Some people have objected that you suffer from a naturalistic fallacy, in that you attempt to call upon the good in people to work together to take care of each other. I wonder how you respond to that?

EOW: Right from the beginning, it was said that I commit the naturalistic fallacy, and it was always terribly false. I’m now involved in a new development in the theory of the genetic origins of human behavior, and it is creating some controversy. We’re shifting emphasis from kin selection to group selection. It doesn’t make a lot of difference insofar as the goodness of humanity is concerned. Kin selection leads to nepotism and group conflict, and if that is the correct version, of course it can be used to commit the naturalistic fallacy. But similarly, if we look at group selection, we have group versus group, the contest between groups and group aggression. That looks to me like the prime mover of human evolution. By the way, this idea was first promoted by Darwin in The Descent of Man. The point is that the naturalistic fallacy is manifestly a fallacy regardless of what view of humanity you take. Even with the Khmer Rouge. If you conclude that people are infinitely malleable, which they did, you can do this-and-that because what they are is what they should be, and so on. No one in their right mind would say such a thing. I never did. What I’ve done is to say the opposite.

What we have in human nature is our inheritance from a prehistoric past going back millions of years. We do have strong predispositions—you can call them instincts—that become dangerous in modern society. So, what we should do is conduct the best research we can, in biology and the social sciences, and find out what it is to be human. And then recognize that these are particular flaws in our nature in a modern techno-scientific world, and work with that knowledge to pull us on through. This is not unlike, say, trying to find the basis for genetic disease, to look for things that make people sick because of mutated genes or pathogens, to find out what causes sickness. Would you then say this sickness is the way things should be, because “is” is “ought”? That is crazy. But the naturalistic fallacy is equally crazy in terms of human nature.

The way I’ve characterized this—most recently in a meeting of the Congress on Innovation and American Progress in Washington—is that we live in a civilization like the Star Wars movie series: we have Paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology. That’s a huge problem! We’re not going to keep our balance and figure out the right things to do as long as we don’t understand or even accept that our emotions are Paleolithic, and that they have an evolved basis. We have to figure out how our institutions came about and decide whether or not they are really viable for us, whether or not we are going to be viable with them, and start moving in the right directions. And that includes a lot of religious institutions. We’ve finally come to realize that religious belief is very dangerous, especially when people are willing to say that something is God’s will. We’re suffering from that idea all the time.

I want to hammer at this. I have not committed the naturalist fallacy and never even thought of it. I see exactly the opposite as being the case.

AD: It must have been extremely frustrating to witness, again and again, blatant misrepresentations of your work by colleagues who ought to have known better.

EOW: It was blatantly unethical. Basically, they were seized by a kind of moral imperative. They believed what they said. Or at least they believed their assumptions about the blank slate.

AD: And they were rewarded for it. Clearly, people like Gould and Lewontin were rewarded for what they did to you and your work.

EOW: That’s why I have a certain cynical feeling towards Gould. Gould was going around attacking racists wherever he found them, especially in the early part of his career. He was the great anti-racism crusader. He acted as though other scientists were all racists or incipient racists. He almost implied that he was the champion who would step out of science as a scientist and fight racism everywhere. He had a technique. I knew him when he was a graduate student following me around. He used to be very polite and solicitous. I watched him develop into a very different kind of person.

He had a technique he repeated. He would examine some 19th century figure—one of his favorites was Louis Agassiz at Harvard, a heroic figure, a founder of the National Academy of Sciences, a man favored by Lincoln and Grant. Then Gould would “discover” a horror—that Agassiz was a racist or that he believed in the inferiority of blacks—and he would eviscerate him. But he would not note this was an almost universal misunderstanding or belief in 19th-century American society. But that was okay. Louis Agassiz’s reputation could hold up. But then Gould had a way of saying “this deeply racist sentiment has not disappeared at all in modern biology. We find it among some modern biologists.” That gave him the launching point to start attacking human genetics.

Gould hated human genetics. And he would go after sociobiology, which sent him into angry fits. And he was massively rewarded. He flourished. Students crowded into his classrooms. This was in the critical years of the ’70s and ’80s. He’d give speeches about racism. And about his paleontology, too. But he was giving lectures and holding forth in reviews constantly about the racism that pervaded American science and the dangers of genetic and biological behavior studies. He received one honorary degree after another. He became famous as a consequence. So, it was rather hard to distinguish what was his pure belief from his personal ambitions. They made him rich and famous.

AD: I met [Harvard Professor of Biology] Ruth Hubbard years ago—it would have been around 2001 or 2002—and I asked her privately what Gould was like. She said he had become a very unpleasant person. I got the sense she had put definite distance between him and her.

EOW: That is really interesting. I don’t know where Ruth is now. I always thought of her as burning with a pure fire. She believed all of this. She was dedicated in an honest way to all of this. She was doing other things, too. She was putting herself into civil rights movement, she was an early environmental activist. She was on the wrong side of the problem that culminated in Nap’s difficulties, but at least she was sincere.

AD: I met Lewontin briefly in grad school. He was brought in to give a talk. I thought it was very odd. Here was a guy who was an intense Marxist, who spent so much time rallying on behalf of the proletariat, who was all about the class struggle. And he struck me absolutely as a BMW-driving, Cambridge-living, Romance-language-phrase-dropping snob.

EOW: You got that. I’ve never fully figured him out. I used to joke that when things got too hot, he could go to his dacha, like a member of the Soviet leadership. He has a place up in Vermont and he could go and be safe there. He was and remains a rather amazing person. He seems to be quite capable of living that kind of contradiction. During the ’60s, we always thought that he seemed alright. He was doing some authentic science, but then around 1970, just about the time that he came to Harvard, he went through this strange transformation and seemed to have become a true believer. He used words like “the proletariat.” He was suddenly using the favorite catchphrases of the communists. He talked about “the running dogs of capitalism.” But he was always a brilliant speaker. When he was in high school, his friends tell me, he was brilliant as an actor in stage plays. His friends thought he would go into theatre. And that seemed to me to be what we were getting, a kind of persona he created, and finally came to believe in.

I’ll tell you a story about all of this. Around 1970, we were searching for someone in population genetics. He looked very good then. And he had this brilliant personality in conversation, this brilliant presentation, a real theatrical power. The search committee decided he was the best person, but this was after he had just adopted his political and public persona and he was known to be joining protests. I remember watching a news report one day about the takeover of a stage at the University of Chicago, where some government functionary had come to speak at the height of the anti-war protests. And to my astonishment, I saw Dick Lewontin rush up and take the microphone!

We had a meeting to take the final vote on Lewontin at Harvard, and a group of the older professors said they were worried about reports of his behavior at Chicago—that he might be disruptive or might have gotten away from genetics, and so would not be the right sort of person to be at Harvard. I made the speech I will regret for the rest of my life: I said we should never accept or reject someone because of their political views. I felt so good about myself making that political speech! “I know several key people at Chicago on the faculty,” I said. “Let me ask them about the key question: Is Lewontin’s new political activism affecting his performance at the University of Chicago, or affecting anything connected with his duties?” And they said, okay, ask and let us know.

So, I called several people who I knew personally. We were all young guys then and they all said, “No, it’s not causing any problems here. He’s doing fine.” That turned out not to be the case. I reported that, and Lewontin came, and then our troubles with him began. I could tell you stories about him and the department that would make for a hilarious evening. But I won’t, except to say that the whole anti-sociobiology thing broke out about three years after he arrived. It was Gould and Lewontin and Ruth Hubbard, mostly oriented by Lewontin, looking to attack sociobiology and to discredit me.

I held up. In response to those attacks, I wrote On Human Nature, which came out in ’78, and it won a Pulitzer Prize, which helped strengthen my position considerably. I was increasingly confident in my own reputation and my security at Harvard. I wrote [entomologist] John Law, who was then a close friend who had done work with me on pheromones. I said, “John, we’ve had Dick Lewontin here three years”—so this would have been about ’76—“so now it’s your turn to take him back for three years.” John sent back a message on a scrap of paper written by the President of the University of Chicago, who was also named Wilson coincidentally. The note said: “From one Wilson to another, no way!” Apparently, they had already been having real problems with him.

I don’t know exactly what happened. No one seems to understand what happened with him. I wish I could tell you.

AD: You said earlier—rightly, I think—that the misrepresentation of your work by people like Gould and Lewontin was “unethical.” Did you ever name their misrepresentation of you as such?

EOW: I never used the word. Scientists don’t use that word. In my first response to the letter in the New York Review of Books, I responded with more anger than I probably should have demonstrated, saying that these were false statements. I didn’t say they were unethical.

AD: Why didn’t you?

EOW: It’s really quite rare for people to cheat and falsify data in science. A lot is made of it, but it is really a rather rare event. I think it is partly due to the fact that you go into science primarily to actually engage in the whole culture, to be a scientist. That’s all based upon a strict code of honesty in reporting, not to be too priggish about it. Further, every person in science knows that if they have even the slightest inclination to be dishonest, they’re going to get caught. And soon. And the more important the discovery, the quicker it will be found. The penalty for dishonesty in science is [reputational] death. Even one act of it can result in death. That’s why I would never have said that they are dishonest. I said that they are wrong, and that they are misrepresenting me. But I didn’t say they were personally being dishonest.

AD: Did you think, then, that the charge was too serious for what they were doing? Or that you didn’t want to get them in trouble?

EOW: If I had called them dishonest or unethical, I would have opened myself up to charges and countercharges. When you’re engaged in a contest with someone, there are certain lethal moves and practices that you don’t engage in. It’s done in Literature, I know, in the humanities and social sciences. There are accusations of dishonesty in those fields fairly regularly. But I didn’t want to open that can of worms, or get into that territory.

AD: I have noticed that about you and your work. You tend to be productive and civil. Personality seems to matter a lot in these controversies. To use a term that some anthropologists or psychologists use, I would say that it is “characterological.” Some people are, well, shall we say, warriors, and that makes them more likely to get into scrapes. You tend to try to be conciliatory, productive, and especially civil.

EOW: I like to say I’m a southerner. I felt somehow it was bred into me that I should be a gentleman and I expect others to be the same. But I quickly learned, as I say in The Creation, that if you use moderation, and reserve, and courtesy, you’ll be the victor in any vicious fight. You also have to have the answers and the truth on your side. But I felt like that’s the winning strategy. I think it is an honest strategy, too. I felt the Evangelicals are good people, and I’ve always asked myself how to deal with people like this who I like in every respect. They’re smart, they’re good, and there is a certain area that says “keep out.” How do you handle that?

AD: Imagine for a moment that you are watching a younger version of yourself struggle with a younger version of Gould and Lewontin. How would you advise that younger version of you?

EOW: I think I would tell him to ignore it. Pay attention, I mean, and respond if there is some really scurrilous thing being said. But, as much as possible, ignore it, and keep working, and you’ll win in the end. I know it isn’t easy during fights. I always said to myself, “Don’t get into a pissing contest with a skunk.” If you ask me what I most resent about that period looking back now, I think the answer is the amount of time I wasted. I spent countless hours talking with journalists who were writing stories about all this. They’d come to me and say, “Well, Professor Lewontin just said so-and-so, Professor Gould just said so-and-so.” Or, “I’ve read in the latest thing that they’ve said this. What do you say to that?” I felt that I couldn’t sit by and let them declare me to be a racist and a proto-Nazi. I couldn’t just say, “No comment.” So, I wasted enormous amounts of energy and time I could have used for something much more valuable. So, my advice would be, this too shall pass. Ignore it as much as you can. Conduct yourself with dignity and with courtesy and let it pass.

The Dean or the President of Harvard never called me in and asked me to straighten myself out. They never said, “You’re giving Harvard a bad name.” It was the other way around. In the ’70s, before Lewontin came after me, he had gone after some other people. Richard Herrnstein was a very good psychologist who had written an article or two on human IQ and the evidence regarding IQ tests. He was studying IQ and heritability which in those days was a really taboo subject. He made himself a target even though he was a decent man whose best work was done in learning behavior of pigeons. He did excellent work, with Skinner.

Lewontin personally picked him out and started badgering him, encouraging others on the faculty who were on the radical fringe, to protest against him. When Lewontin found out that Herrnstein had been invited to give a lecture or serve on a committee, Lewontin would call them up and tell them not to have him.

AD: That’s really awful.

EOW: Well, this was happening. It got so bad. People knew about it at Harvard. Herrnstein wasn’t the only professor being followed around by protesters stirred up with wrong ideas. The dean of the faculty at the time, Henry Rosovsky, formed a committee, and I was invited to be on it—this was before I had my run-in, so maybe it was ’73 or ’74. We met in the dean’s office to discuss how to protect Richard Herrnstein from Lewontin and others. There were a couple of others who had joined in the pursuit. The conclusion was that there was nothing we could do. We were committed to freedom of speech, so what could we do? But we called in Herrnstein for our second meeting and told him we understood what was happening and regretted it very much, and if he needed counseling or support that we could give it to him without risking the principle of academic freedom, and that this committee would be there ready to help him. I’m sorry that didn’t get written up anywhere. But that’s what happened at the time.

AD: That’s really remarkable.

EOW: Unfortunately, I don’t know of any written record of it. It’s probably in the minutes of the dean’s office somewhere.

AD: Did you ever find that kind of support at Harvard?

EOW: Unfortunately not. In fact, I had several close friends in the Organismic and Evolutionary Biology department who would sometimes speak to me and just say they were sorry it was happening. One was my close colleague Bert Hölldobler. We were working all the time together in the lab and field. We would spend long periods of time talking about it and trying to figure it out, trying to understand Lewontin. He gave me his unstinting support, and made that clear to Lewontin and others.

But no one else said anything or did anything. I think they kind of weren’t 100 percent sure about me. They thought maybe there was something to what Lewontin or Gould were saying. No one ever offered any sympathy or any kind of help. At one point when Lewontin had unleashed some outrageous statement, [evolutionary biologist] Ernst Mayr read it and asked Lewontin, “Why are you doing this? Why are you attacking Ed all the time?” And Mayr told me that Lewontin had said, in effect, well, it’s just my nature or personality.

AD: That would be pretty darned ironic, if he said it was just his nature!

EOW: He didn’t know what else to say to Mayr. I think he didn’t want to get into a fight with him. Mayr never offered me sympathy personally. On two occasions, Lewontin approached me after a Department of Biology faculty meeting, and said that he wanted me to know that his attacks on me were not personal or motivated by professional jealousy. They were motivated by his ideological beliefs. He said that to me twice.

AD: What was your response?

EOW: I can’t remember. I think I just said, “Thank you, Dick.” It was beyond professional jealousy, he said, so I accepted what he said. Obviously, we should have standards of civility.

AD: You mentioned your correspondence with Norton regarding Tierney’s book, expressing your concerns. I wonder if you kept that.

EOW: After all this settled down, I moved from Knopf to Norton, partly because of a brilliant editor I’ve been working with. The person I corresponded with was McFeely, I think. There was a twist there. I didn’t pledge at the time that I would not go with Norton. I still feel that Norton and McFeely made a mistake. If I feel that, it doesn’t stir up too much. I think I simply told McFeely at the time that Tierney’s book is a pack of lies. That it’s false and something should be done about it. It put them on the spot. I don’t know if it changed any of their policies.

AD: Norton refuses to answer any questions from me, which I expected. I do know the book became a finalist for the National Book Award, which is outrageous.

EOW: That is very disturbing. But I’m solid with Norton now. I’ve sort of forgiven them. But if I find they’re considering another book by Tierney, I’m going to remind them of the fiasco.

AD: You are one of the few people on the planet with that kind of ability, that kind of leverage.