Art and Culture

The Schenker Controversy

History is complicated, people are complicated, and Schenker himself was a complex individual.

In the realization of my plan, I will not permit myself to be distracted by anything in the world, and it is my conviction that the truth, however anybody may try to assault, ignore, or otherwise abuse it, will nevertheless prevail.

~Heinrich Schenker

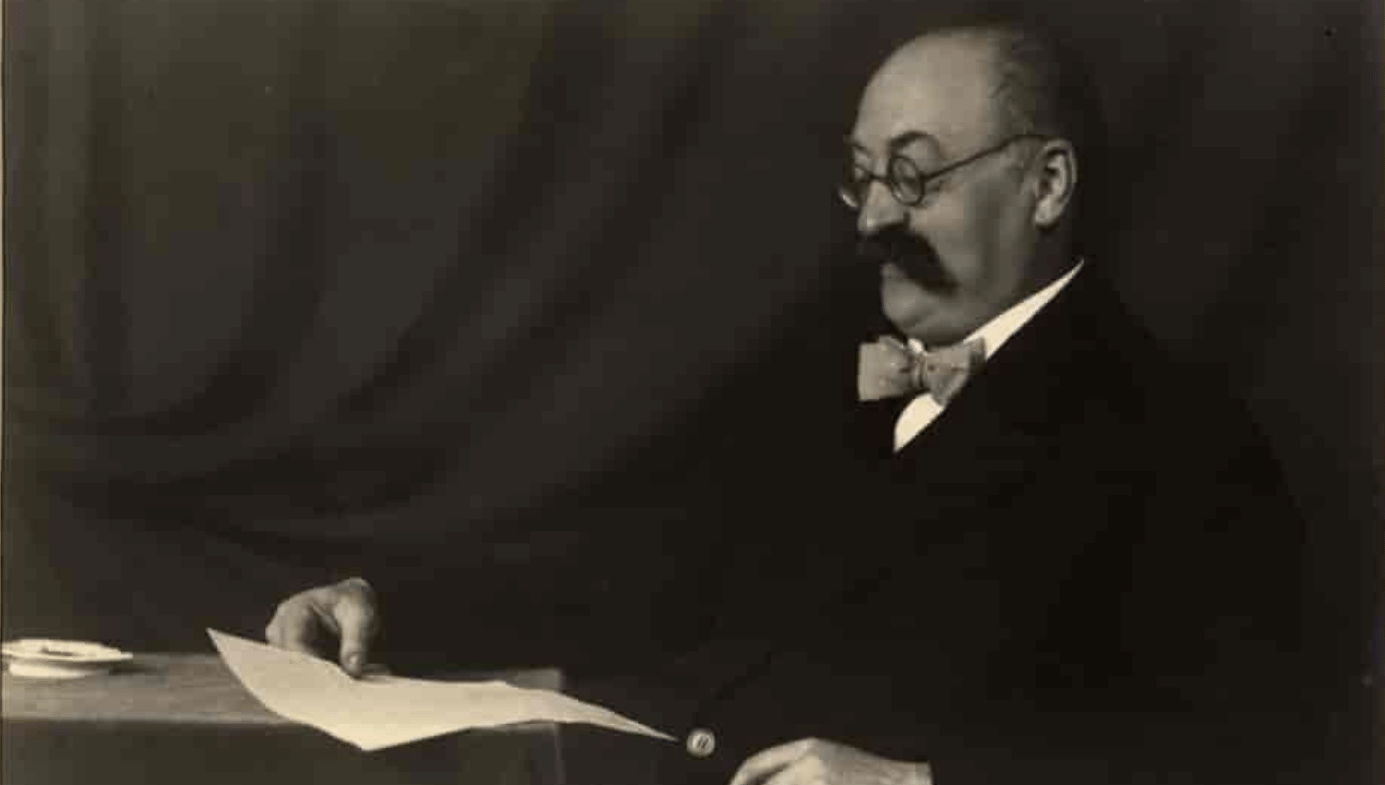

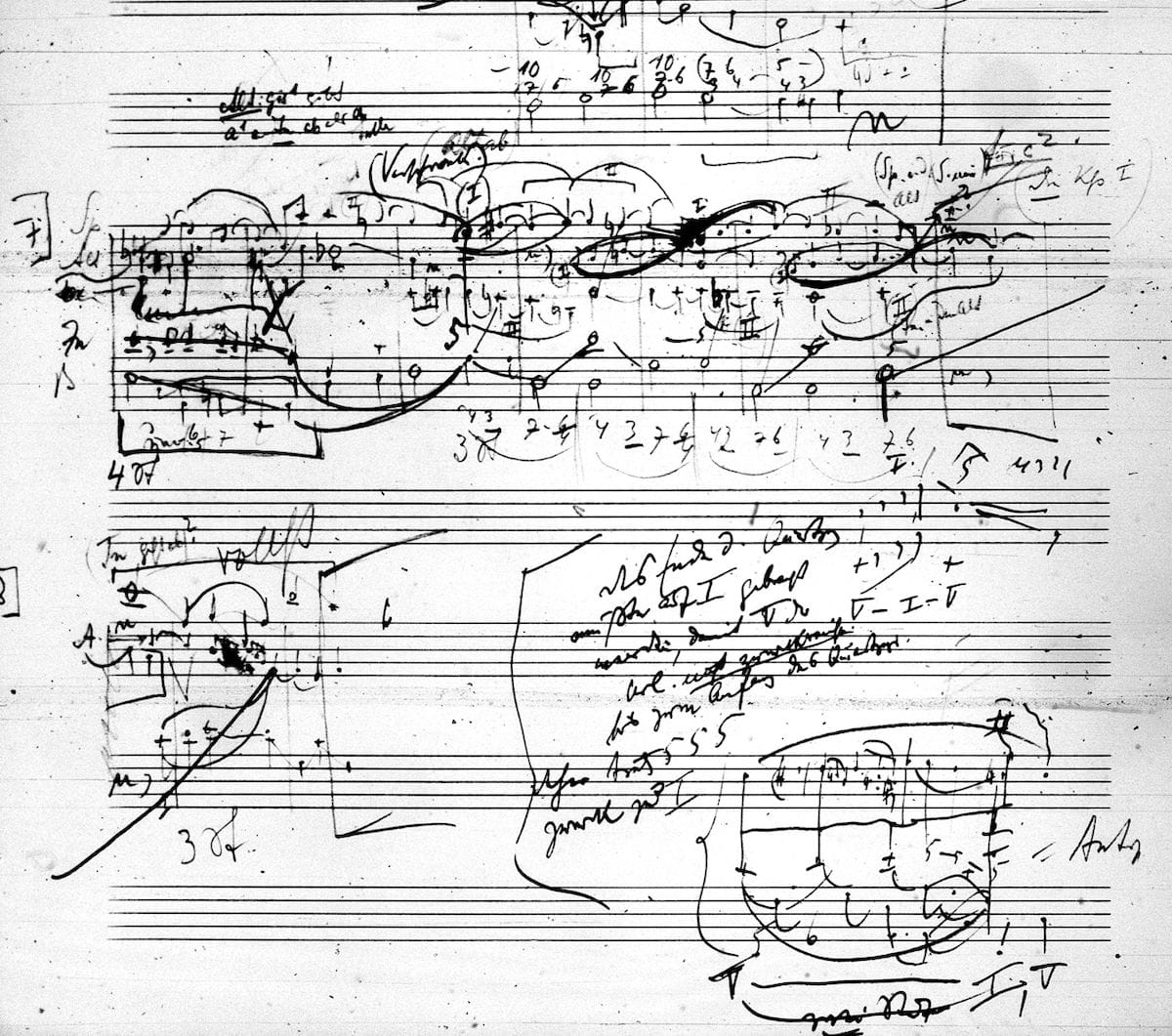

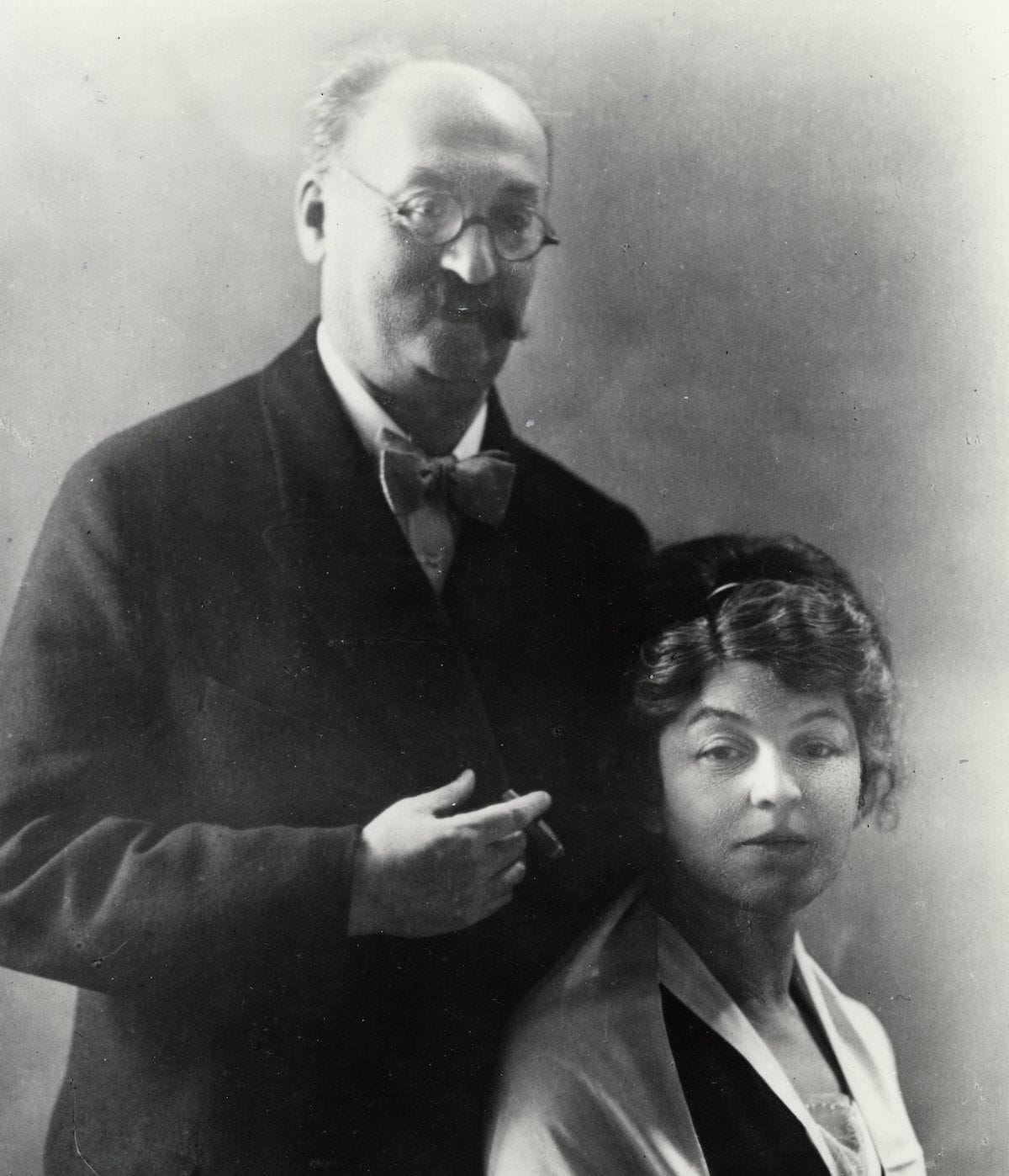

Located in the Neue Israelitische Friedhof [the New Jewish Cemetery] just outside Vienna, the epitaph of one of the greats of music theory reads, “Here lies he who perceived the soul of music and proclaimed its laws in the spirit of the greats like no one before him, Heinrich Schenker.” The author of the epitaph lies buried beneath it. While Schenker might still be unknown to the general public and even to many music theorists, his glowing self-assessment has been taken seriously by scholars since the 1960s. With a gigantic musical mind and vision, Schenker has assumed the status of an Albert Einstein or a Sigmund Freud in the arena of classical music theory, upon which he bestowed the gift of his analytical approach, and his superb ear and musicality.

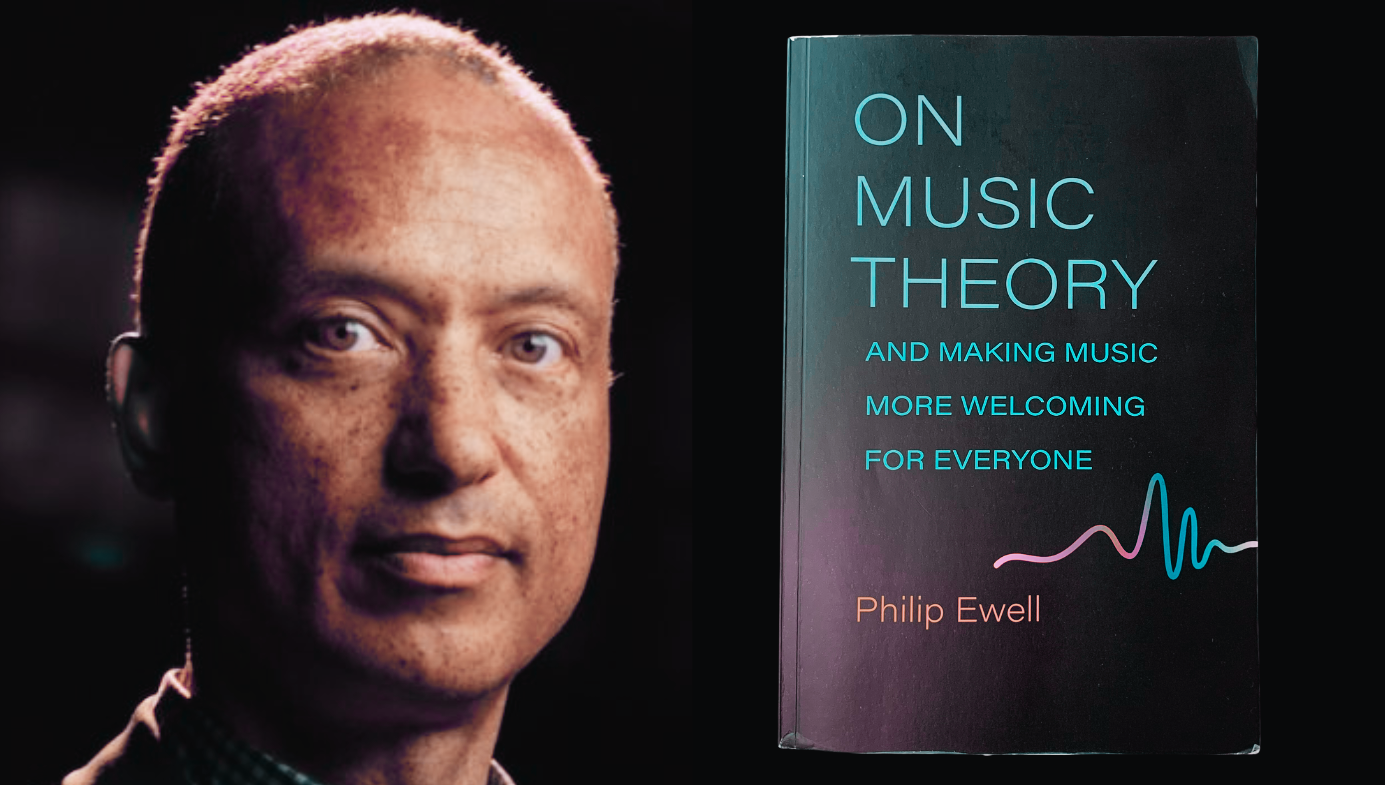

Yet virtually the entire profession of music theory in America now believes that Heinrich Schenker was a “virulent racist”—a Jewish Nazi sympathizer, no less. In July 2020, the Journal of Schenkerian Studies, which I founded at the University of North Texas, and I were both subjected to a massive cancellation attempt over our efforts to counter an attack on Schenker, Schenkerian music theorists, and the methodology itself, by Philip Ewell of Hunter College. I, too, was branded a “racist” for my critique of Ewell’s views and the university initiated an ad hoc investigation of me and the journal in the name of “combating racism.” In response, I filed a lawsuit against my own university and some of my colleagues, in which litigation is ongoing.

Among the many accusations made against Schenker and his legacy was the insinuation that Schenker’s disciples—most of whom were German Jewish refugees who fled the Nazis—deceptively colluded to hide the racist character and origins of Schenkerian music theory. In this recent retelling of history, these emigres were said to be responsible for imposing what critical race theorist Joe Feagin has called a “White Racial Frame” on music theory, to the exclusion of blacks and people of color. But is it really plausible or historically accurate to associate Schenker’s refugee students with contemporary white supremacists? Were these German Jewish emigres, and their Jewish students here in America, socially constructed as “white”? The claims being made about Schenker are not only false, but are part of a legacy of antisemitic views and practices that plagued both him and his students during the 20th century, and continue to harm the reception of his work today.

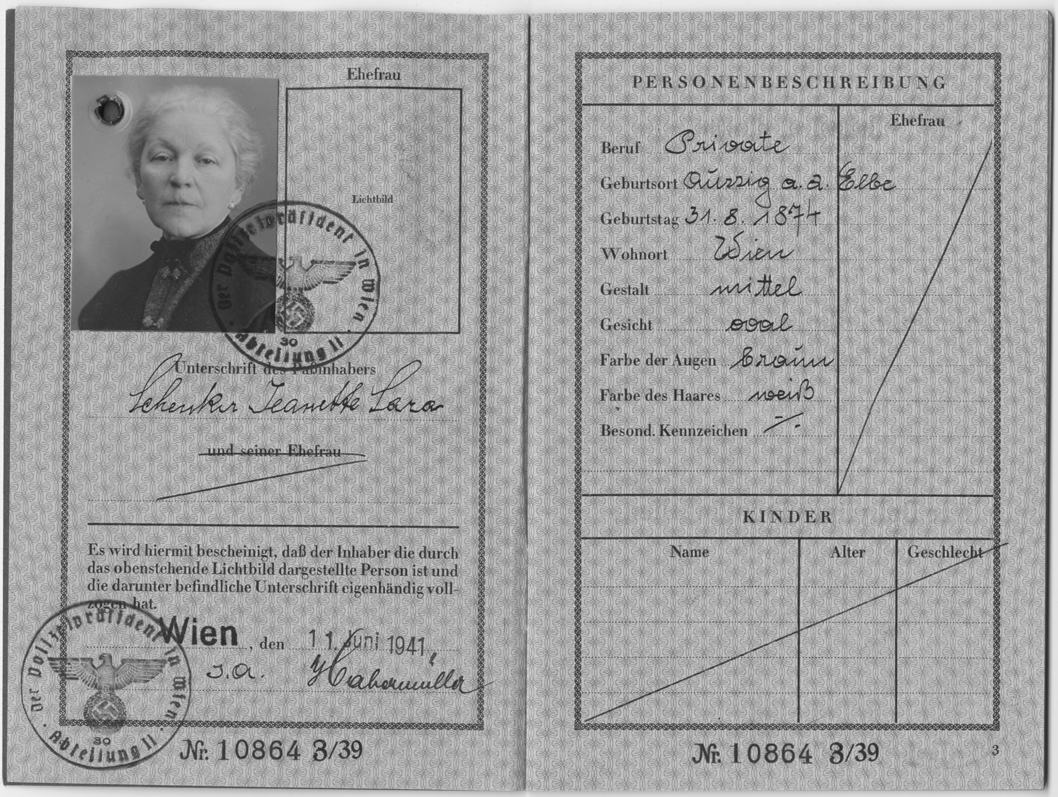

In fact, in German-speaking Europe during the interwar period, Jews were differentiated from Germans not by skin color but by the designation “non-Aryan,” and, after Hitler came to power, by a “J” stamp or the names "Israel" and "Sara" inserted into their passports. Once the Nazis conquered Europe and large parts of European Russia (the former Pale of Settlement), the euphemistic designation "nicht Arisch" became a death sentence.

And when they arrived in America, Schenker’s students continued to be subjected to racial prejudice. Many major American universities were reluctant to hire Jewish refugees due to the antisemitic attitudes widely prevalent among faculty and administrators. And if they were hired, they were deliberately underemployed. For example, when Schenker’s student Hans Weisse joined the music faculty at Columbia University during the 1930s, he was engaged only as an adjunct lecturer, despite the fact that he had studied with Guido Adler as well as Schenker, and had earned a prestigious doctorate in musicology from the University of Vienna. He was forbidden from teaching Schenker’s theories.

Ewell’s claim that Schenker was an adherent of Nazi ideology and an admirer of Hitler dates back to Schenker’s own lifetime. As early as the 1920s, his critics accused him of hiding his Jewish identity and supporting the Nazi cause. In response, Schenker noted that he had refused to convert to Christianity, unlike many of his Jewish detractors. In a letter to his student Otto Vrieslander on May 6th, 1923, he wrote:

All baptized Jews everywhere, who adopt foreign names, foreign religion, foreign language, have appointed me, tax-free, to the position of “swastika wielder”—though I am the only one among them who has no business in these matters.

Schenker emphasized his refusal to undergo baptism:

I have not been baptized and, when asked, confessed my Jewish faith with pride and love, indeed with the utmost conviction that no writer of history can share with me, not even the most enlightened Jew.

In 1925, a parody issue of the contemporary music journal, Musikblätter des Anbruch, printed a series of satirical responses to the question “What does New Music mean to you?” in the voices of various luminaries. Schenker was the only one singled out for portrayal as an antisemite and Nazi militarist. His supposed response to the question (written by the authors of the parody) is a deliberately pompous run-on sentence that’s impossible to render into clear English:

I received your survey, “What does New Music mean to you?” and I am extremely astonished that this survey was sent to me. As you may know, I am the most important living music writer, pianist and composer today and for a great many years in my books and pamphlets as well as in my arrangements of Beethoven and other works, which are the best of all existing, that have existed, and will exist, and even that could have existed, according to which New Music is hardly a music at all, and that after Beethoven and Schumann (hallowed be the name) and perhaps Brahms, but then no more [music] was created, and everything only became clear once I discovered that it is so, and that I will proclaim it to humanity, because we Germans do not allow ourselves to be mocked, and the God of all still exists, and the Jews will experience that their world empire is defeated in the name of German Art, in the name of Beethoven, in the name of Bach, in the name of Schumann, in the name of Brahms and in the name of Heinrich Schenker from Podwoloczyska. May God grant this.

The reference to the Jewish “world empire” alludes to the notorious antisemitic fabrication, The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, and the promise that “we Germans” would overthrow Jewish hegemony in New Music was an antisemitic slur unlike anything Schenker himself ever wrote or uttered. The parody also equates Schenker with a “Piefke”—Viennese slang for a Prussian militarist. And Schenker's assessment of Schoenberg and Hindemith as far inferior to the great Classical masters is twisted to suggest that Hindemith is a bad composer because, like Schoenberg, the actual composer of the tone-poem Pelleas und Melisande, he is a Jew.

Schenker privately responded to these slanders in a diary entry on September 20th, 1925, in which he lamented that “the people who accuse me of Nazi allegiances, or of insincerity, such as by hiding my Jewishness, do not prefer to resort to factual refutations…”

Two years later, in an August 1927 letter to his friend Moritz Violin, Schenker responded to the July violence in Vienna with this prognosis of its significance:

The events in Vienna have shocked me. Who knows how things will turn out as a result. In any event, they signify one step closer to the abyss. The Germans are sinking quickly, I refer to the Germans in general—in less than ten years one will be able to read the fate of the Jews on the brow of every German, just as on the brow of every Jew.

Confronted with ascendant Nazism in 1933–34, Schenker rejected the Nazi concept of biological racism and its concomitant antisemitism. Unlike many contemporaneous thinkers (including German sociologist and musicologist Theodor Adorno and Austrian Jewish philosopher Martin Buber), Schenker was already expressing his opposition to the regime by mid-April 1933, two-and-a-half months after the Nazis seized power.

However, until the end of the first week of April 1933, even Schenker—for all his prescience in 1927 about the unhappy destiny of the Jews—seriously underestimated the virulence of Hitler and the Nazis’ antisemitism, and the extent to which it would motivate their future actions. But he was hardly alone in this respect. In early 1933, there remained considerable uncertainty about whether Hitler’s inflammatory cant was a matter of sincere conviction or demagogic posturing. With the Nazis now in power, many Europeans—including many German and Austrian Jews—waited to see how the new regime would behave.

Schenker lived in Vienna, so he was spared the immediate dangers faced by Jews in Germany—his German students and colleagues would serve as his eyes and ears within the Third Reich. This may be part of the reason that Schenker initially failed to recognize the full depth of eliminationist hatred there. In a diary entry on April 2nd, he wrote that the Nazis’ opposition to his work was “unconscious” and complained that it was caused by “complete ignorance of the content and value of my achievement” rather than antisemitism. By the middle of April, however, a series of developments within Germany had disabused him of this delusion.

The April 7th Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service resulted in the firing of thousands of Jews and university professors who had refused to swear allegiance to Hitler. On April 11th, Goebbels informed Schenker’s friend and informal student, the famous conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler, that the Nazis would assume full control of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. In an exchange of letters published in the German press the following day (which Schenker’s diary confirms he read), Goebbels condemned all support for the further participation of Jewish musicians in German culture. And on April 13th, Furtwängler was forced to submit information on all Jewish and half-Jewish orchestral musicians to the regime, including copies of their contracts.

During a concert conducted by Furtwängler in Mannheim on April 29th, 1933, an attempt was made to force the three leading Jewish orchestral violinists to sit at the back of the orchestra, and Furtwängler was subsequently reprimanded in the press for his “lax attitude in the Jewish question.” That same day, Schenker recorded in his diary that a letter he’d received from another student, the composer Otto Vrieslander, had been “sharply critical of Germany, but rightly so!” This statement is among Schenker’s earliest condemnations of the new regime.

Despite these ominous developments, many remained reluctant to acknowledge the lethal danger Nazism posed to Europe, and to European Jews in particular. On May 14th, 1933, Schenker wrote a letter to his student Johann Felix-Eberhard von Cube, a German gentile who was, at that time, still a supporter of the Nazi party. Schenker noted the new constraints on teaching “Jewish music theory,” and remarked that “Professor [Reinhard] Oppel in Leipzig … leads a national socialist ‘cell,’ in which he continues to teach Schenkerian analysis, now as before, insofar as this is possible.”

In a letter from May 1933, Oppel informed Schenker, who had inquired about their mutual friend, the Viennese Jewish pianist Richard Glas, that “Glas in Kiel naturally is not in an easy position under the new circumstances, nevertheless it appears from his last letter that he will be able to hold out. I trust his ability to bite through [sich durch zu beissen].” Glas evidently believed that he might still be able to continue teaching and performing. Indeed, he remained in Germany until 1938, when he finally fled to London. Clearly, Schenker, Oppel, and Glas were worried about the negative impact of Nazi antisemitism on Glas, but at that juncture (1933) all of them underestimated the seriousness of the situation.

Oppel continued to collaborate with the Nazis until mid-July 1933, by which point he had become disillusioned, a development he reported to Schenker in their correspondence at the time. In a letter to Schenker on July 6th, 1933, Oppel wrote, “The exams are over and finally I have more time, especially since I am also taking leave of absence from the Party.” In a diary entry on July 23rd, Schenker recorded his response, in which he advised Oppel to disassociate himself from the Nazis: “Letter to Oppel dictated. I strengthen him in his skepticism.” In his reply on September 26th, Oppel confirmed, “I now keep everything that has to do with the [Nazi] Party at bay.”

Today, Ewell claims that “Schenker was a fervent German nationalist whose racist convictions lay at the very heart of his theories on people and on music.” But Schenker—and many other German Jews besides—believed that the superiority of German culture was based upon language, not on race. In his now infamous 1921 essay, “The Mission of German Genius,” Schenker praised German as “the one true language,” and the “most exalted of all languages,” as the gateway to exalted German culture.

But Hitler and the Nazis denied the possibility of Jews integrating with German culture. In Mein Kampf, Hitler is explicit on this point: “[The Jew's language] is not a means for expressing thoughts but a means for concealing them. When he speaks French, he thinks Jewish, and while he turns out German verses, in his life he only expresses the nature of his nationality.” On April 12th, 1933, this view was reaffirmed by Karl Paul Schmidt, who later became press-chief of the Bureau of Foreign Affairs. Schmidt published 12 theses in the German press that paved the way for the national book burnings on May 10th. His fifth thesis stated: “The Jew who can only think Jewish but writes German lies. … We therefore demand from the censor that Jewish works appear in Hebrew. If they appear in German, they are to be labelled as translations.”

Schenker’s reaction to these developments was to reaffirm and proudly proclaim his affiliation to Judaism. In a letter to his student Felix Salzer on June 30th, he wrote: “God in his infinite wisdom has called upon a Jew [Schenker himself] to explain the art of music, who will thus remain first and last the true praeceptor Germanorum [‘teacher of the Germans’].” In addition, Schenker often associated his Jewish identity and faith with his musical theories. For example, in a diary entry on May 21st, he wrote: “[Oswald] Jonas … is shocked by my profession of Judaism. Parallels: in the cosmos, the one origin in God—in music, the one origin in the Ursatz [fundamental structure]—thus monotheistic thinking in both cases. Everything else with respect to world and music [is] a heathen adherence to the foreground.”

After the Nazis banned jazz in 1933, Theodor Adorno observed: “The [Nazi] ordinance that prevents the radio from broadcasting ‘Negro jazz’ may have created a new legal reality—artistically, however, this drastic verdict only confirms what had long been decided on the basis of fact: the end of jazz music itself. Because regardless of what you mean by White and Negro jazz, there is nothing here to rescue.” Compare Adorno’s undisguised contempt with Schenker’s more generous contemporaneous remark: “The recently repudiated dynamic of jazz was almost more fun than that of nationalistic art.”

As Barry Wiener observes in a forthcoming study, “Schenker’s letter demonstrates both that he considered Nazi culture to be beneath contempt, and that he judged the art of African-Americans by purely artistic criteria. Even though Schenker admired jazz no more than other manifestations of popular culture, he preferred it to the artistic products of the ‘master race.’”

The current revisionist portrayal of Schenker as a racist is predicated upon quotations from his letters and diary entries, as well as his publications. To understand Schenker’s writings, a strong command of German is a sine qua non, so that his words can be understood in his native tongue. Equally necessary is knowledge of the context in which they were written: when Schenker was writing privately to his friends, students, and colleagues, he was often expressing himself in bantering or ironic tones informed by a series of shared experiences—animosities and allegiances and prior communications—and references to books and articles shared within the group. Various shades of meaning and connotations are often superimposed.

Example 1: Decontextualized mistranslation and misinterpretation

Ewell quotes an English translation by William Drabkin of Schenker’s May 1933 letter to his student, von Cube, who was still a Nazi supporter at this point. This is what Schenker wrote:

Das geschichtliche Verdienst Hitlers, den Marxismus ausgerottet zu haben, wird die Nachwelt (einschließlich der Franzosen, Engländer, u. all der Nutznießer der Verbrechen an Deutschland) nicht weniger dankbar feiern, als die Großtaten der größten Deutschen! Wäre nur der Musik der Mann geboren, der die Musikmarxisten ähnlich ausrottet: dazu gehörte vor Allem, daß sich die Massen dieser in sich versponnenen Kunst näherten, was aber eine—contradictio in adjecto ist u. bleiben muß. „Kunst“ und Massen haben nie zusammengehört, werden nie zusammengehören. Woher nun aber die Quantitäten der Musik- „Braunhemden“ nehmen, mit denen es gelingen müsste, die Musikmarxisten hinauszujagen?

Unfortunately, Drabkin’s translation of this passage is both inaccurate and misleading in certain key respects, most notably his reference to “our intrinsically eccentric art” in his translation of the second sentence. A more accurate translation of the passage reads as follows:

Hitler’s historical achievement of having rooted out Marxism will be no less gratefully celebrated by posterity (including the French, the English and all the profiteers of the crimes against Germany) than the great deeds of the greatest Germans. If only the man were born to music who would similarly get rid of the musical Marxists; for this, above all, would require that the masses were able to come closer to this art, convoluted in itself, [and which] is and must remain a contradiction in terms. “Art” and “the masses” have never belonged together and never will belong together. And where would one find the huge numbers of musical “brownshirts” who would be required to hunt down the musical Marxists?

Given the events of the previous month, Schenker’s expressed admiration for Hitler’s successful extirpation of Marxism and his declared to wish to see “brownshirts … hunt down” musical Marxists is at best a distasteful provocation. But it is also plausibly an indication that, in the narrow matter of anti-Marxism, he had allowed himself to be seduced by the idea that the enemy of his enemy was his friend. Many intellectuals saw the Nazis’ rise to power as an opportunity to settle old scores. On April 4th, 1933, Thomas Mann noted in his diary: “As for the Jews ... that Alfred Kerr’s arrogant and poisonous Jewish garbling of Nietzsche is now excluded, is not altogether a catastrophe; and also the de-Judaization of justice isn't one.”

Nevertheless, it is important to bear in mind that the point of this single passage—written in a private letter to a pro-Nazi student—was not to celebrate Hitler but to express Schenker’s bottomless disdain for the Modernist obscurantists (Hindemith, Schoenberg, Stravinsky, etc.) whom he despised for creating art that was unintelligible to the masses. In isolation, it is certainly insufficient to convict Schenker of pro-Nazi sympathies, especially when set against his earlier unequivocal criticisms of the Party and its ideology quoted above.

Schenker's reference to Hitler is further contextualized by Bruno Stürmer’s “Open Letter” to Hindemith published in Die Musik in October 1930, a communication that Schenker had distributed widely among his intimates and praised as “very strong and effective,” including in a postcard he had sent to von Cube. The passage in question reads, “You don't trouble yourself at all about the [current dire] situation. ... You know that you are a Leader [Führer] and at least, that you were considered a Leader and could be one... .” For Schenker, probably alluding to Stürmer, Hindemith imagines himself to be a musical “Führer,” analogous to Hitler in the political realm; but Hindemith can never be a successful populist like the Führer precisely because he cannot communicate with the Volk through his unintelligible, convoluted art.

In fact, Schenker, no less than the composer Alban Berg, was an ardent supporter of Engelbert Dollfuss and Austria’s Austro-Fascist Christian Social Party, just like Baron von Trapp (memorably portrayed by Christopher Plummer in Robert Wise’s 1965 film, The Sound of Music). As Wiener explains:

During the early 1930s, Schenker supported the Austrian clerical party, the Christian Socials, which opposed both the Communists and the Nazis. Schenker’s political stance was akin to that of most Austrian Jews, who perceived Christian Social Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuß as a staunch defender of the Jewish community. Given the limited political options in Austria, even Karl Kraus accepted Dollfuß as a “lifesaver” [Lebensretter]. After Dollfuß was murdered in 1934, Schenker wrote in his diary, “Radio: appreciation of the statesman Dollfuß. … Dollfuß towers like a giant above all other statesmen, he brings to mind Moses’s leading of the Jews out of Egypt. An Austrian heroic age!” Because Dollfuß had opposed the Nazis, Arturo Toscanini, Europe’s leading musical antifascist, conducted the Verdi Requiem in his memory at the Vienna Staatstoper on 1 November 1934.

Example 2: Misconstrual of quotation

As further evidence of Schenker’s putative racism, Ewell quotes him as saying “‘race’ is good, ‘inbreeding’ [Inzucht], however, is dismal.” But Schenker was criticizing, rather than endorsing, racial purity. Had Schenker intended to attack racial mixture, he would have used the term “interbreeding” (Mischung or Bastardierung)—the terms used by Nazis for the mixing of races. In this, he differed, for example, from the Expressionist painter Emil Nolde, who wrote: “Some people, particularly the ones who are mixed, have the urgent wish that everything—humans, art, culture—could be integrated, in which case human society across the globe would consist of mutts, bastards and mulattos.”

On January 1st, 1934, the 1933 Hereditary Health Act began to be enforced in Nazi Germany, legalizing the compulsory sterilization of individuals suffering from hereditary diseases. The purpose of this law was the “elimination of the unfit for reproduction” and the prevention of all “racial mixing,” specifically of Jews and blacks with Germans. On January 13th, 1934, Schenker wrote to his friend, the musicologist Anthony van Hoboken, expressing his hope that the latter would leave Nazi Germany and resettle in Grinzing, on the outskirts of Vienna. Schenker’s comment about racial mixing must be elucidated and evaluated in this context.

That you have acquired the plot of ground in Grinzing is ample grounds for us all to rejoice very much; but why have you added to this wonderful report words that make a reversal of the purchase seem possible? Thus I await the ultimate decision—the superstition in me commands it so—then I will pay off with wish and blessing. Vienna today seems to me to be the most plausible location for you, just because here—don’t laugh—the Jews can make their mark in music and show many varieties (e.g. annoyance, entertainment). “Race” is good, “inbreeding” of race, however, is dismal (as the Romans used to say: even virtue must not be overdone); Art occupies a completely different place, so it is perfectly appropriate in the world that in Vienna racial aliens still represent interesting flecks of color (Jews, Hungarians, Slavs, Italians, etc., etc.)

Schenker wanted to stress that, in Vienna, Jews were still allowed to perform music, and foreign peoples—including Jews like himself—added “interesting flecks of color” to the cultural mix. He was praising—not condemning—racial diversity. He meant that, even if certain racial characteristics are valuable, he considered too much communal separatism to be undesirable.

Example 3: Tendentious ellipses

Ewell writes approvingly of Schenker’s Austrian biographer, Martin Eybl, because “[Eybl] acknowledges Schenker’s racism forthrightly.” He specifies that “in a section entitled ‘Hierarchie der Völker’ (‘Hierarchy of Peoples’), Eybl builds a case for Schenker’s racism,” and quotes his own translation of a paragraph from Eybl’s monograph on Schenker:

The term “Menschenhumus” is based on the idea that Germanism unequivocally constitutes the best natural conditions for the development of geniuses: in “Menschenhumus of the highest category” the “German genius” is manifest. … Anyone who considers the term “Menschenhumus” as a simple translation of the burdened conceptual pair of blood and soil is ignoring the pseudo-scientific bases of national-socialist racism and its predecessors.

This quotation from Eybl is a central plank of Ewell’s argument. But Ewell’s ellipsis replaces a key sentence in the German original that categorically refutes and undercuts his own argument. It reads: “Again, Schenker does not argue on the basis of race, but of German national [culture].” [„Wieder argumentiert Schenker nicht rassistisch, sondern Deutschnational.”]

Also omitted are the important two sentences that immediately follow this quotation, and which reinforce the same thought: “At no point does Schenker attempt to explain the superiority of Germanness genetically. The fact that the German people can be defined by language and culture forms the open and nebulous prerequisite for Schenker's German nationalism.”

It can be difficult for Americans today to understand that racism in the interwar period was not simply a matter of skin color. W.E.B. Du Bois wrote about how difficult it was for him, who had always faced color-based discrimination in America, to confront the reality of the “Arisch”/“nicht Arisch” dichotomy and prejudice in pre-war Europe. As he recalled:

A German student was with me, and when I became uneasily aware that all was not going well, he reassured me. He whispered, “They think I may be a Jew. It’s not you they object to, it’s me.” I was astonished. It had never occurred to me until then that any exhibition of race prejudice could be anything but color prejudice. I knew that this young man was pure German, yet his dark hair and handsome face made our friends suspicious. Then I went further to investigate this new phenomenon in my experience.

Du Bois came to recognize that being Jewish can be like having an “invisible disability”—one does not see it immediately, but in a given cultural context, as in Europe after the Nazis assumed power, it could be dangerous, even fatal to the bearer. The truth of this observation is proven by the dire fate that befell those of Schenker’s Jewish students who were unable to escape in time. On January 8th, 1945—10 years after Schenker succumbed to ill health—his wife Jeanette also died in the Theresienstadt ghetto where the Nazis had transported her following her arrest in 1942.

Schenker's animosity to Modernism explains why he wrote as he did, leveraging Hitler’s purging Germany of Communism to articulate his artistic resentments. But that fact does not make Schenker a Jewish Nazi. Schenker's thinking was never in line with Nazi ideology, and, as a Jew, he rejected its pseudoscientific racism. Furthermore, he modified his views of “Germanness” [“Deutschtum”] towards the end of his life, and became more egalitarian in his opinion of who could participate in high musical culture, which he reconceived as “a meritocracy of the spirit.” In this sense, Schenker was very much like Thomas Mann, who evolved in a similar direction, from being intensely pro-German to anti-Nazi and egalitarian. Later lauded as the “conscience of Germany,” in his earlier years, Thomas had denigrated democratic and pacifistic writers like his brother, Heinrich, as “Zivilisationsliteraten” [“progressive and overly civilized”], admitting that a speech by Goebbels was “roughly how I was writing thirty years ago.”

Any attempt to associate Schenker's German-Jewish emigre students in the United States—Hans Weisse, Oswald Jonas, Felix Salzer, Ernst Oster, and others—with Fritz Kuhn and the contemporary German-American Bund reverses the roles of victims with perpetrators, and resonates with the trope familiar from Nazi propaganda, “Die Juden sind unser Ungluck!” [“The Jews are our misfortune!”]. The forced mass exodus of Jewish scholars after 1933 resulted in a “crisis in the university world,” as described by the McDonald Commission of the League of Nations. It must be noted that those few of Schenker's students fortunate to make it to these shores were never as enthusiastic about “Germanness” as Schenker had been, even prior to their forced emigration, and certainly not post-1933. Nor did they all share Schenker’s implacable hostility to Modernism. Surprisingly, even Oster (the scion of rabbis) deigned to perform Schoenberg’s piano music in a public concert. Salzer analyzed Schoenberg and Stravinsky; Oster’s student Edward Laufer, my teacher, developed a linear approach to analyzing post-tonal music.

History is complicated, people are complicated, and Schenker himself was a complex individual. Dying in early 1935, in spite of a sometimes-remarkable prescience, he lacked the benefit of hindsight. The interwar period was fraught with trepidation but also dilemma and doubt; the reality of Nazi power was something with which Germans, Jews, and Europeans more broadly were forced to come to terms, and the path the new regime would follow in the early 1930s was ominous but uncertain. People were compromised by the political reality, by their friendships and conflicting personal, religious, and political commitments, and by their own biases and obsessions (such as Schenker's hatred of Modernism).

Schenker wasn't perfect—like almost everyone else during those fearful and confusing years, he was human, all too human. My intention is not to canonize him, nor to make him a subject of hagiography. He is a subject of history, and an ability to appreciate nuance, context, and complexity is what makes for truly sophisticated historical inquiry. This idea is being trampled by crude interventions that seek only to condemn and denounce. People outside of music and music theory may wonder why this debate concerning Schenker is of such tremendous importance. At stake is not simply the narrow matter of Schenker’s reputation, but the integrity of scholarly inquiry itself—the pursuit of truth and historical accuracy.