Politics

The Eyes Have It

For the “new intellectual,” ultimately, the way forward has to be paved with nuance and understanding.

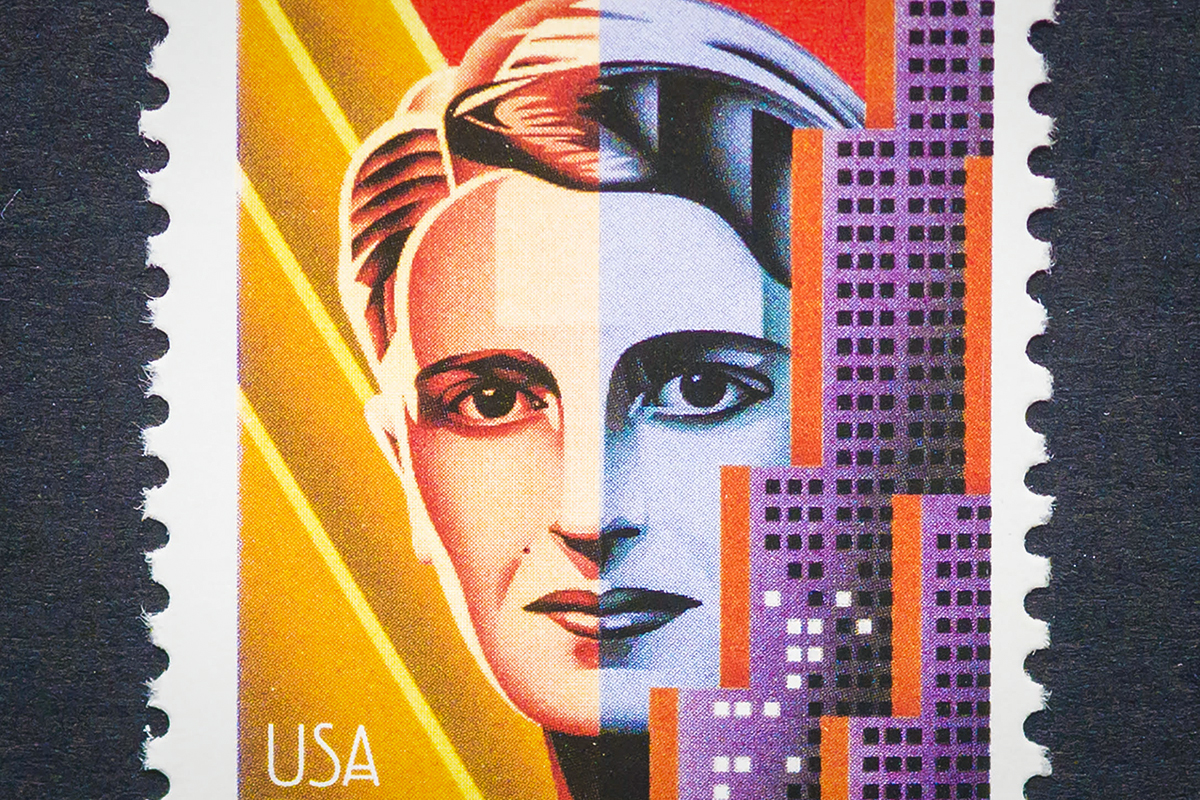

Ayn Rand was not conventionally beautiful, but her dark cinematic eyes held the young in her thrall throughout most of her impressively eventful life. The world will probably be seeing more of them in the coming months, as the 40th anniversary of the enigmatic novelist-philosopher’s death approaches.

More than a half-century ago the great—and, alas, irreplaceable—American scholar Allan Bloom became aware of the spell she could cast. He first started noticing it around the time he became aware of a decline in serious reading among his students. As the University of Chicago professor later recounted in The Closing of the American Mind, it became particularly evident whenever he asked his large introductory classes which authors and books really mattered to them. Most of the undergrads fell silent, he wrote, or else were puzzled by the question. There was generally no text to which they looked “for counsel, inspiration or joy,” he remarked. But one exception kept popping up.

There always seemed to be, he marvelled, a student who mentioned Atlas Shrugged, a work “although hardly literature, which, with its sub-Nietzschean assertiveness, excites somewhat eccentric youngsters to a new way of life.” And rather more of them than did Allan Bloom or, indeed, pretty much anyone else in the United States who has ever tried to hawk philosophy to the masses. Rand’s book sales overall stand at around 30 million, with hundreds of thousands more each year, and probably rather more this coming year.

Not only is she sought-after for her two best-known novels—the other being The Fountainhead—but also for her nonfiction. Her slim volumes of collected essays and old newspaper columns and other outtakes comprise an apparently fathomless vault from which the Ayn Rand Institute routinely cobbles together regular offerings for the lucky kids. One survey by the Library of Congress listed Atlas Shrugged as second only to the Bible in terms of campus popularity; an incredible accomplishment. All the more so in an era of Twitter, Facebook, and all the other intimations of the shortened attention-span. Say what you will about Rand, nobody ever described her as a light read.

A random internet search throws up an impressive litany of fans from the entertainment world, including Oliver Stone, Rob Lowe, Jim Carrey, and Sandra Bullock. Even the late professional wrestler James Hellwig, better known as The Ultimate Warrior, bellowed her praises, which might add some context to those rollickingly individualistic pre-fight interviews he used to do back in the WWE glory days. Oh, and let’s not forget Brad Pitt and Vince Vaughn. Which is particularly interesting, I think, since Jennifer Aniston (also a Rand fan) replaced the first with the second after Pitt ran off with Angelina Jolie, who’s also on record enthusing about Rand’s “very interesting” take on the good life.

In politics and economics, Rand had her youthful followers, too, and here again one sees the youth-appeal angle. Probably her best-known disciple is the former Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan, who is rather ancient now. But back when dinosaurs still roamed the Earth, Greenspan declared that the high empress of the libertarian Right “taught me that capitalism is not only practical and efficient but also moral.” Like the young and philosophically restless undergrads in Allan Bloom’s classes, the British health secretary Sajid Javid also discovered her early on, and apparently still reads the courtroom scene in The Fountainhead every year. Or rather, as the cool libertarian kids in the black jeans might prefer to put it, it still reads him.

Ayn Rand never looked like the type of person to gather such popular devotion. A diminutive Russian Jew, she was born Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum, in St Petersburg, in 1905, the child of bourgeois parents. The daughter of a self-made pharmacist, she loathed socialism, particularly as it affected her family at the time. Philosophy offered solace from an early age. In her schoolbook, according to Anne C. Heller, author of the nicely detailed Ayn Rand and the World She Made, she copied out quotations from Descartes (“I think therefore I am”) and Pascal (“I would prefer an intelligent hell to a stupid paradise”).

Aged 12, Alisa cowered with her parents and sister as the family-owned pharmacy was ransacked by marauding Bolsheviks. They fled the city for Crimea. Later, presumably with that horrible experience in mind, she began writing stories about men of resolve with lantern jaws who stand their ground, resolutely staring down the mobs who would sack their businesses. She also haunted the primitive cinemas of the time, soaking up the silent American films of the era and yearning to be a part of the perfect world they revealed: our own.

In 1925, after getting a degree from the University of Leningrad, Alisa Rosenbaum lit out for the New World, assuming her better-known identity shortly after her arrival in Chicago. Various explanations have been offered for the new name. Either it was taken from the brand of typewriter she carried around with her (according to one slightly implausible legend), or it was a Semitic term of maternal endearment (according to a somewhat more plausible one), literally “my eyes.” Whatever its inspiration, the name-change was also intended to protect her family back in the USSR—an unusually selfless act for the woman who would champion the virtue of selfishness and inveigh against the cardinal vice of altruism.

Rand was never terribly big on humour, but it must have tickled her—diehard atheist that she was—to have got her first big break working as a New Testament extra on Cecil B. DeMille’s 1927 film, The King of Kings. Another of the extras, a handsome young man named Frank O'Connor, grabbed her attention. Eager to grab his before he vanished back into the biblical crowd, she tripped him up. “I took one look at him and, you know, Frank is the physical type of all my heroes,” she later recounted. “I instantly fell in love.” They married a couple of years later.

In 1943 she published The Fountainhead, her bestseller about an idealistic architect who blows up his construction project when he finds its design has been tampered with by yobbish bureaucrats. Fourteen years later came Atlas Shrugged, a 1,084-page epic about a future decade in which big government and trade unions strangle individualism, leading to a strike by the “men of the mind” intended to bring the “moochers” to their senses. One reviewer at the time described the book as “a masochist’s lollipop.”

These novels, like her later nonfiction writings, were underpinned by objectivism, the author’s worldview that prized laissez-faire capitalism and its ethical corollary, egoism (which Rand, who struggled for quite a while with the English language, clunkily identified as “egotism”). In her idealised state, people are no longer required to pay tax but simply make donations, if they wish and as they see fit, to some sort of non-centralised government agency. Nevertheless, the same state would also be expected to maintain a formidable defence and police forces and a robust judicial system, all of which Rand thought could be funded by regular lotteries.

“I am primarily the creator of a new code of morality which has so far been believed impossible,” she modestly informed an interviewer in 1959. “Namely, a morality not based on faith, not on emotion, not on arbitrary edicts, mystical or social, but on reason.” In fact, one could probably argue—as the New York scholar and self-confessed fan, Chris Sciabarra, does in his book Ayn Rand: Russian Radical—that there’s something weirdly Marxian in all of this, or at any rate dualistic in a classically Russian sense.

Rand was once asked to systematically define the philosophy she claimed as her own while standing on one foot. This she did brilliantly, defining it thus: metaphysics—reality; epistemology—reason; ethics—rational self-interest; politics—capitalism. She certainly had style. Rand could be a natural media performer when the occasion called for it, as in her intellectually electric series of conversations with Alvin Toffler for Playboy in 1964. But it was on television that she shone best, in particular her interviews with Phil Donahue and Johnny Carson. The trademark black cape certainly helped, as did the gold broach fashioned in the figure of a dollar. Then there was the husky voice and ever-present cigarette puffed ostentatiously between denunciations. And those neon eyes.

Adolescents and young adults were forever in her sights. Her first nonfiction primer, in 1961, was called For the New Intellectual. In the context of the work, “new” plainly meant “young”—which is to say, the point at which many of us tend to get caught up in the realm of pure ideas unencumbered by messy pragmatic or emotional concerns. Sometimes her relationships with youth took interesting swerves. Barbara and Nathaniel Branden, whom she and Frank met while the other couple were in their early 20s, were such acolytes. Rand, then pushing 50, quickly designated Nathaniel as her “intellectual heir apparent.” The four travelled together frequently doing public appearances.

In her memoir, The Passion of Ayn Rand, Barbara recalls them driving together for hours (she had a pathological fear of flying) from Toronto to New York, and how for much of the journey Nathaniel couldn’t stop looking into Rand’s eyes. Later, Rand summoned the other three to her studio in the East Thirties of Manhattan and demanded to have a “consensual affair” with Nathaniel. Barbara, “looking into her marvellous eyes” felt unable to refuse. How could she? “The question isn't who is going to let me,” Rand used to say, “it's who is going to stop me.” And the idea that anyone could stop her would have made Howard Roark himself laugh.

I must declare an interest. As a youngish man, I was rather fond of Ayn Rand. Up to a point, I sort of still am. Her novels never really grabbed me, but I liked what she had to say about the importance of open debate, the need to let people go about their own lives as they see fit, her abiding distrust of the chattering classes, and her wariness of governmental overreach. Delving a little deeper, though, I began to experience doubts. Her belief in the supremacy of existence, for example, seemed like a rehash of the early materialists, in particular Ludwig Feuerbach from the early 19th century.

What was more, the flame-haired uber-men of Rand’s imaginings came on like the worst dinner-party guests one could possibly hope to entertain. Their speeches would prattle on for dozens and dozens of pages without interruption—not even a diffident sheep’s cough by one of the assembled listeners was permitted, still less the shattering of glass as guests dove through the French windows to escape. Little matter, less relevance. Every philosopher has holes in their ideas. To this, most of them admit. Not so Rand, who sold herself fabulously as a total package—an all-or-nothing proposition.

If that seems like a slight exaggeration then try and spend a few hours in the conversational company of some of her more strident followers. The Canadian journalist Jeff Walker, devotes an entire book to this matter entitled The Ayn Rand Cult, in which he excoriates both the substance and style of the movement she gathered around her. Walker pummels the claims made about Rand’s originality, literary talent, and morality. And his book contains startling anecdotes drawn from within Rand's inner circle, including vivid descriptions of non-smokers being ostracised from the chain-smoking author’s social gatherings. (She later died of lung cancer.) Homosexuality was for a long time also a big no-no for the true objectivist.

Walker homes in on the tendency to humiliate those who fail to toe the party line—not only on the big questions of religion or what constitutes the best theory of knowledge, but also on what ought to be relatively minor issues like whether or not an adherent enjoys particular novels or wears a moustache. As Walker argues, this is the stuff of youth cults everywhere and at all times; here, a touch of the apocalypse; there, a dash of utopianism; and everywhere else, the conviction that a New Jerusalem lies just around the corner. After all, as he says of the juvenile urge that Rand’s work often adroitly tickles, “weakness and confusion don’t feel anywhere near as good as power and certainty.” The young simply “lack the critical thinking skills to filter her onslaught.”

Whatever one may say of Walker’s arguments (and, in fairness to Rand, parts of his critique could be described in the same hysterical terms he reserves for her), that last bit does touch on something at once terribly ancient and incredibly up-to-date. In places, he might just as well have been writing about the social justice activists of the 2020s, with their similarly radiant certainties and haughty contempt for disagreement. But why stop there? No doubt, some of the more vulnerable youngsters who followed Socrates and Plato were seized with a similar conviction that theirs was the last and definitive word on all things. The young hooligans who ransacked Rand’s father’s business in Russia probably felt the same way.

For the “new intellectual,” ultimately, the way forward has to be paved with nuance and understanding. This echoes Karl Popper’s excellent observation that the wholesale adoption of any rigid set of ideas is for the birds. Nor is it much intellectual fun. It is rare, Popper pointed out, that in a debate between two respectful participants one will succeed in converting the other, much less getting him to join some philosophical cult. But it’s equally unusual for either of them to go away from a properly conducted conversation with precisely the same position as that from which they began. Concessions and refinements will have occurred. Initial positions will have undergone a degree of modification, and the sum of human knowledge improves accordingly.

In the meantime, I suppose, Ayn Rand will continue to sell and sell. All power to her. I still happen to think that, for all her faults, she is worth reading carefully—and almost equally worth discarding as maturity beckons. As for the ultimate verdict on her philosophical merits, the eyes would appear to have it.