Beatles

Peter Jackson’s ‘Get Back’—A Review

The recording sessions appear harmonious, and although they only have five songs that they are confident enough to play on a cold rooftop in January, the gig above their Apple office—the laziest possible location—goes without a hitch.

Somewhere, I have a copy of the Beatles’ final film, Let It Be, furtively acquired during the 1990s. It’s a third- or fourth-generation VHS recording from Christmas 1980, shortly after the murder of John Lennon, when it was broadcast late at night on the BBC. As far as I know, it had never been shown on British television before and has never been shown since.

When you consider that it is possible to buy entire series of Time Team and Wheeltappers and Shunters Social Club on DVD, it seems extraordinary that an Oscar-winning film starring the biggest band of all time has not been available on video for decades and has never been released on DVD or Blu-ray. Never streamed, almost never broadcast, the Let It Be movie is the proverbial red-headed stepchild of the Beatles’ story.

It has long been assumed that McCartney, in particular, did not want to be reminded of it. It was he who instigated the 2003 curiosity that was Let It Be… Naked, a reworking of the band’s ropey final LP (recorded before Abbey Road but released after). It used an alternative take of ‘The Long and Winding Road’ stripped of Phil Spector’s Hollywood orchestration, removed two pieces of harmless filler (‘Dig It,’ ‘Maggie Mae’), and belatedly included the best song from the sessions (‘Don’t Let Me Down’). Released only a few months after he had reversed the songwriting credits to “McCartney-Lennon” on a live album, it smacked of historical revisionism. Macca would not let it be.

The January 1969 sessions that produced these songs have acquired a reputation for being extremely miserable, and it is easy to see why. None of the Beatles has had a good word to say about them for 50 years. None of them attended the film’s premiere, and McCartney was the only one to show up at the Oscars to collect an award for a soundtrack he hated. Lennon described the music as “the shittiest load of badly recorded shit, and with a lousy feeling to it, ever.” This, admittedly, was during his scorched earth interview with Rolling Stone in 1970, but his surviving bandmates were still saying much the same 25 years later when they were interviewed for the Anthology TV series. Harrison described it as “painful … the winter of discontent.” Starr admitted that “it could get boring” and recalled “many heated discussions.”

That this was an unhappy time seems to be confirmed by Harrison’s departure from the band during the sessions. It took several off-camera negotiations over a period of days to persuade him to return, and the film shows McCartney and Harrison having testy exchanges. The whole thing feels bleak from the outset, and it seems inarguable that this was a grim chapter in the Beatles’ story. The camera never lies.

Or does it? Get Back, released on Disney+ this month, urges us to reconsider. Based on this documentary, the Sunday Times recently described the Let It Be sessions as “the last time the band were happy.” Quite a turnaround. Have Beatle historians been wrong for half-a-century, or is this the most audacious attempt yet to rewrite the band’s history?

Editing Get Back was the lockdown project of Peter Jackson. As you might expect from the director of The Lord of the Rings, it is so long that it is split into three parts. The story—barely discernible in Let It Be—is that the band are rehearsing to make an album, a TV special, and a live show, and are against the clock because Ringo has to start filming The Magic Christian with Peter Sellers in a few weeks. The band have given themselves the added constraint of recording all tracks live, with no overdubs. The rehearsals start in a Twickenham film studio under the full glare of the cameras before moving to a more homely basement of the Beatles’ Apple office.

The film crew were there to record a half-hour TV show, but when that idea was ditched, it was stretched into a feature film. Fly-on-the-wall documentaries were a novel idea in 1969, but now that it has been expanded to nearly eight hours, it has become something even more modern. It is essentially reality TV.

Get Back is a vastly better film than Let It Be. It provides an unrivalled insight into the Beatles’ creative process. It looks stunning. At times it is very funny. But if you think the Beatles are having the time of their lives, you may be underestimating the ability of 20-something Liverpudlians to laugh in the face of adversity, particularly when every unguarded comment could be broadcast to the world.

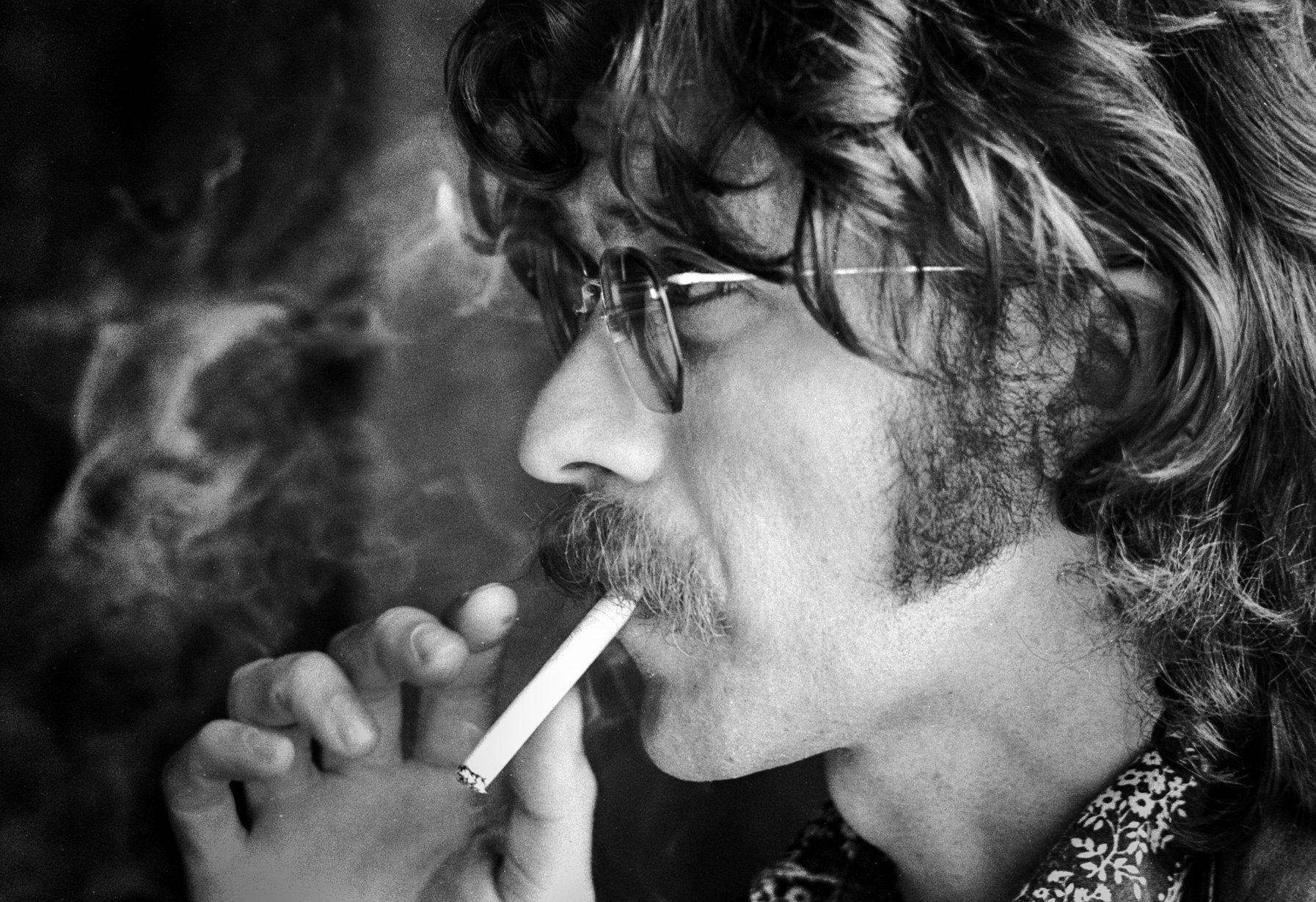

The band always acknowledged that the mood of the sessions improved when they moved to the Apple studio and recruited keyboardist Billy Preston as a temporary fifth member. But nothing in Get Back changes the fact that those first two weeks in Twickenham were horrendous. Forced to get up early (by their standards), they all look exhausted. Lennon, who has been dabbling with heroin, is detached from proceedings and barely says more than the ubiquitous Yoko Ono (who, contrary to Beatles folklore, is remarkably unobtrusive). Unable to concentrate on new material for long enough to master it, they try to keep their spirits up by playing bad versions of golden oldies from their Hamburg days.

Let It Be’s director, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, a 28-year-old minor aristocrat, is a mildly preposterous young fogey who spends most of the documentary smoking cigars and getting in front of the camera. Faced with four men who are in no mood to take direction and who mock him behind his back (Jackson has left out most of their jibes), he bobs along in a sea of chaos while imaging himself to be the ship’s captain.

Harrison has brought along several promising songs, but they are too slow for a live show. Lennon has turned up with little more than the bare bones of ‘Don’t Let Me Down’ and ‘Dig A Pony.’ Aside from some half-hearted and doomed attempts to re-record ‘Across the Universe’ and develop ‘On the Road to Marrakesh’ (which would later become ‘Jealous Guy’), these would be his only substantial compositions for the band until his hilariously self-absorbed effort ‘The Ballad of John and Yoko’ three months later. (That song spent three weeks at number one in the UK singles charts, dislodging Tommy Roe’s ‘Dizzy,’ which had topped the charts for a week, ending the six weeks ‘Get Back’ spent there. If the Beatles were in decline in 1969, no one had told the record-buying public.)

McCartney, on the other hand, was brimming with creativity. In addition to producing most of the material for the album, he brings along a third of Abbey Road and a good chunk of his first solo album. We see him writing ‘Get Back’ before our very eyes while he waits for Lennon to show up one morning. If anything, he has written too much, and the band skip from playing bona fide classics like ‘The Long and Winding Road’ to wasting time on trivial tunes such as ‘Teddy Boy’ and ‘Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,’ apparently unable to tell killer from filler. Despite the deadline, they display an extraordinary lack of urgency.

There then follow several scenes so eye-opening it’s incredible that they have been kept quiet until now. At the end of the first episode, Harrison casually announces that he’s quitting the band. It has been a long time coming. During a passive-aggressive argument between Harrison and McCartney earlier in the episode, Harrison had said “you don’t annoy me anymore” like a loveless wife with a one-way ticket to Rio in her handbag. He had spoken openly about leaving the band earlier in the week, to which McCartney responded by leading the band through yet another rehearsal of ‘Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,’ a song they hated. And yet Harrison’s abrupt departure still took me by surprise because the moments immediately leading up to it were not recorded.

Beatles fans have long argued about which straw broke the camel’s back. The Let It Be film led many to assume that McCartney’s general bossiness was to blame, but a row between Harrison and Lennon seems to have been the immediate trigger. Newspapers at the time reported that the pair had come to blows, claims denied by both parties but later confirmed by George Martin. Whatever the truth, neither Lennon nor Harrison denied that there was an argument and it is striking how quickly Lennon lightens up once Harrison is gone. He may be over-compensating for the band being a man down—he is at his best when his back is to the wall, he later tells McCartney—or he may be genuinely relieved to be rid of the Quiet One. Either way, he becomes lively, talkative, and engaged for the first time.

In the second episode, we hear a private conversation between Lennon and McCartney discussing what to do about their lead guitarist. George is AWOL and Lennon finally arrives at lunchtime after leaving his phone off the hook all morning. The pair retire to the cafeteria to get away from the cameras and we only know what was said because, almost unbelievably, Lindsay-Hogg has hidden a microphone in a flower pot. They are both aware of the problem—they should be taking Harrison’s songs more seriously. They also know that McCartney has assumed leadership of the band since manager Brian Epstein’s death in 1967, and that the others want a greater say in how the songs are arranged. Interestingly, McCartney says he has always seen Lennon as “the boss” and is happier being the deputy. But they also know that McCartney’s ideas tend to be pretty good and that while he might not want to be the boss, he does want to get his own way. This tension would never be resolved and within eight months the band was effectively finished.

“Musical differences” has become a knowing euphemism for “seething hatred” whenever bands split up, but if this frank conversation is any guide, the differences between Lennon, McCartney, and Harrison in January 1969 were indeed primarily musical. Lennon is far more calm and pragmatic during this exchange than his public persona implied. There is no suggestion that either man wants the band to break up (yet) and they both assume, for reasons that are never quite explained, that Harrison will return.

The most memorable scene comes the following day. It is a Tuesday and George has been gone since the previous Friday. Ringo is unwell. John and Yoko have been up most of the night taking drugs and watching TV. Paul, with Linda in tow, is uncharacteristically listless. They are supposed to be playing a gig in a week’s time and they have yet to nail a single number. They should rehearse. They could go home. Instead, they just sit there chatting nonsense. A bottle of wine is produced. A bemused Peter Sellers pops in to say hello. Lennon is in his element, mugging for the camera and cracking one-liners. McCartney seems almost delirious, overwhelmed by the absurdity of a film crew capturing every moment of the world’s biggest band—minus one member—doing absolutely nothing. “What we need is a schedule,” he says in his earnest Hard Day’s Night voice. “A programme of work. Achieving something every day.” The band has hit rock bottom and it is hilarious. Who knew that the Beatles breaking up could be so funny?

This was to be the last day of rehearsals in Twickenham. Thereafter, they move to the Apple basement where the notorious bullshitter “Magic” Alex Mardas was supposed to be building a studio. With Billy Preston in tow, the band eventually manage to produce something fit for public consumption (the ‘Get Back’ single) and the clouds begin to lift. Two weeks into rehearsals, they are still making heavy weather of fairly simple ditties like ‘Two of Us’ and ‘I’ve Got a Feeling,’ but things are starting to click into place in time for the live show which has been postponed until the end of the month, venue TBC.

By the time we get to the third episode, the band is on a roll and it is all smiles. The recording sessions appear harmonious, and although they only have five songs that they are confident enough to play on a cold rooftop in January, the gig above their Apple office—the laziest possible location—goes without a hitch. And so they end their career as a live band doing what they had done in the Cavern: playing rock and roll to people on their lunch break.

If these four men on the rooftop hate each other, they hide it extremely well. They do not look like a band that is about to split up. And yet the fact remains that the Beatles did split up and they all remember the “Get Back” sessions as the moment when a split became inevitable. They strongly suggest on camera that they’ve been miserable for some time. “Ever since Mr Epstein passed away, it’s never been the same,” laments Harrison, who describes the band as being “in the doldrums.” “We’ve been grumpy for the last 18 months,” says the normally indefatigable Starr. “Nothing's going to change my world,” sings Lennon in a reheated version of ‘Across the Universe,’ before adding “I wish it fucking would.”

But comments like these have to be weighed against hours of evidence in Get Back showing the band clearly enjoying each other’s company and being highly creative. So where does the truth lie?

When enough years have passed, a photograph becomes the only thing you remember about the day it was taken. Is it possible that the Let It Be film implanted memories in the Beatles’ heads that dislodged happier recollections? McCartney is beginning to think so. He told the Sunday Times that “I definitely bought into the dark side of the Beatles breaking up and thought ‘God, I’m to blame.’ It’s easy, when the climate is going that way, to think that. But at the back of my mind there was this idea that it wasn’t like that. I just needed to see proof.” Confirmation bias? Perhaps, but Harrison’s recollections of the “Get Back” sessions in the 1995 TV anthology also seem to have been entirely based on scenes from the Let It Be film.

Throughout the sessions, Lindsay-Hogg can be heard asking himself and others what he’s doing there. What is he filming? What is the purpose of it? By the time Let It Be was released in April 1970, the Beatles had broken up and the purpose of the film had become to explain why they had broken up. The answers it hinted at were, in crude terms, that Paul was bossy and Yoko was domineering. Beatles historians have always known that this explanation is overly-simplistic if not flat-out wrong. Get Back makes a strong case for treating the Let It Be version of events with scepticism, but is Get Back the whole truth?

It seems odd to accuse an eight-hour epic of cherry-picking, but even eight hours is a fraction of the 57 hours of video and 160 hours of audio that were recorded. More than 80 percent of the video footage hit Peter Jackson’s cutting room floor, although much of it is available on bootlegs and online. When Doug Sulpy and Ray Schweighardt catalogued every second of every recording from the sessions in their book Get Back: The Unauthorized Chronicle of the Beatles’ Let It Be Disaster, they found little to challenge the conventional narrative that it was the band’s nadir. The scene in which the Beatles (minus George) do nothing for hours is highly amusing in episode two of Get Back, but hours of tedium have been edited down to minutes of wisecracks. Having been exposed to the full recordings, Sulpy and Schweighardt describe this day as one of “unrelenting monotony.”

There are plenty of bum notes and fluffed lines in Get Back and it is understandable that Jackson would choose the takes that are easiest on the ear, but perhaps we need to hear those countless hours of tuneless jamming to understand why the band recalled this period with so little fondness.

Finally, we must consider the possibility that the Beatles shone so brightly that their idea of fun was a cut above that of us mere mortals. Perhaps there is nothing to resolve between the Beatles’ memories and the video evidence. Perhaps Get Back is showing the Beatles having a pretty good time working on classic songs, and also showing the Beatles having the lousiest month of their career. If it all looks tremendous fun to us, it is because our lives at their best will never be as good as the lives of the Beatles at their worst.