Last summer’s George Floyd protests ignited a firestorm of political apologies that continues to blaze. Across the country, local officials from Greensboro to Glendale have been issuing formal statements of apology for historic injustices against African-Americans and other minority groups. Sad to say, most of these apologies won’t achieve the outcomes (forgiveness, trust, and optimism about a shared future) that the apologizers are hoping for.

Research has shown (surprise, surprise) that apologies can be very effective at promoting forgiveness and building trust in some situations. When I harm you—but then own up to my wrongdoing, promise to change my ways, and take steps to undo the damage I’ve caused—I’m taking advantage of the most effective forgiveness-promoter scientists have yet identified. Apologies can also work when celebrities and corporations use them for public-relations damage control following the hot-mic gaffe, the private peccadillo, and the ill-advised tweet.

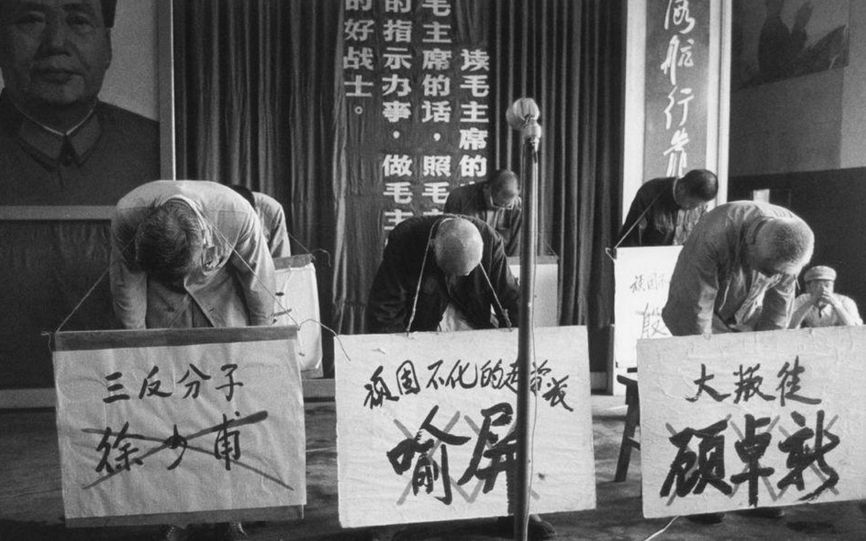

But unlike people who deliver personal apologies and public relations apologies on their own behalf, political apologizers generally aren’t addressing their own behavior, especially when the transgressions—such as those that dominate public discussion today—occurred generations ago. Because political apologizers have no skin in the game—their apologies don’t expose them to legal consequences, financial penalties, or even moral condemnation—they can seem perfunctory and insincere. Effective apologies ought to hurt.

Another reason political apologies don’t work, perversely, is precisely because they have become so common. People value resources more when they are rare than when they are plentiful, and political apologies are no exception to this rule—a phenomenon that the social psychologist Tyler Okimoto and colleagues have labeled the “age of apology effect.” The political apology has become the moral equivalent of covering your mouth when you cough: people judge you harshly if you don’t do it, but you don’t come off as a paragon of virtue just because you do.

Also, political apologies are quickly forgotten. In a 2011 study involving people from three countries that were deeply affected by Japanese atrocities during the Second World War, participants were asked whether Japan had ever offered a formal apology. Only 13 percent of participants correctly answered yes; 22 percent erroneously believed the Japanese had never apologized. Two-thirds of respondents had no idea. In actuality, Japanese officials have apologized dozens of times (albeit, in some instances, ham-handedly) for Japan’s wartime behavior.

Americans’ memories for political apologies are little better: In a 2008 study of American adults, 60 percent said they had heard of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, but only 30 percent were aware of President Bill Clinton’s 1997 official apology. More than a generation has passed since Clinton’s apology, so surely even fewer could recall it now—so much less so the fact that Tuskegee also led to a successful lawsuit, hearings on the senate floor, a formal government inquiry, and a new federal law requiring researchers to obtain informed consent from their research participants. Making matters worse, many people now believe that the Tuskegee researchers deliberately infected their patients with syphilis (they didn’t). Our poor collective memory exaggerates harms—as if the truth weren’t appalling enough—even as it minimizes subsequent efforts to address those harms.

There’s a final reason political apologies don’t work: They’re not very good. The social scientist Marieke Zoodsma and her colleagues recently examined 20 American political apologies in order to count up the number of linguistic elements they contained, out of 10, that are known to make apologies effective. It’s a list that includes, among other elements, praise for victims, requests for forgiveness, and promises of reparations. The 20 apologies left a lot of rhetorical money on the table: On average, they contained fewer than five of the 10 critical elements. All 20 apologies acknowledged the harm, but only two of them accepted responsibility and only four offered reparations or material compensation to victims.

Which takes us to the contentious issue of reparations. When people seek forgiveness from others they’ve harmed, they often try to compensate them: In lawyer-speak, they try to make them “whole.” On balance, these offers of material compensation—even when they fall far short of the damage done—make a difference. American political apologizers rarely mention reparations because they’re in no position to provide reparations: they simply lack authority to divert public funds into such compensatory schemes. (To be sure, victims sometimes are compensated through litigation: The participants in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study were awarded $10 million in a successful class-action lawsuit.) Under this powerful constraint on their authority, politicians’ compensatory actions are generally limited to public investments in underprivileged communities, official days of remembrance, and new memorials (and yes, as we’ve seen, the toppling of old ones). Would more tangible forms of compensation strengthen political apologies further? We don’t really know.

Even without talking about material reparations, America can improve its political apologies. First and foremost, our political apologies should include more of the linguistic elements that make them sincere and complete. Second, when possible, apologies should be delivered by people who were directly responsible for causing (or, at least, turning a blind eye to) the harmful acts—and they should be delivered to people who were directly harmed (or their loved ones). Although we’ve grown quite accustomed to them, political apologies delivered by proxy perpetrators to proxy victims are just weird.

Third, political apologies should start in the community, not the mayor’s office or a city council meeting. When apologies spring up from the grassroots—through public demonstrations, petitions, or surveys that demonstrate strong public support, or through coordinated activity in the churches, schools, and business community—people judge the apologetic group as more remorseful, more sincere, and more forgivable than when the apology comes from a stuffed shirt behind a microphone.

Finally, we have to stay mindful of our fallible collective memory. We’re prone to keeping our wounds green by easily recalling the awfulness of the past while forgetting about the courage and honesty of those who took steps to heal those wounds. We need to find ways to recall the hopeful chapters of the past, not just the horrific ones.