Canada

Watching My Great Nation Lapse Into a Cult of Self-Abasement

I wasn’t a patriot until it had all gone;

then I would have sold my soul to buy it back.

~Tanya, in Malcolm Bradbury’s Eating People Is Wrong

For more than 20 years, from the mid-’70s to the late-’90s, Morningside, a three-hour daily broadcast that mixed current events with human-interest stories, reigned as the flagship program on CBC Radio. The host of the show during its most successful run was Peter Gzowski, a veteran journalist widely embraced as something very much like Canada’s favourite uncle. On air, Gzowski was affable, chummy, his exchanges with guests routinely punctuated by his signature moist, ingratiating chortle. He was, in fact, that rare man who deserved his very own adjective: avunctuous.

During one broadcast, Gzowski recalled an incident that had occurred at the annual invitational golf tournament he hosted to benefit adult literacy programs across Canada. As one participant, standing next to Gzowski, leaned thoughtfully on his club, another drove a golf cart over his toes. Although it was unclear from the telling whether the cart-driver was American, the first golfer was obviously Canadian, since, shifting gingerly from foot to aching foot, he could only plead, “sorry.” Gzowski shared this anecdote with evident delight, since it struck him as so endearingly, because emblematically, Canadian.

But Gzowski’s soaring contentment with this view of his country and countrymen was no less emblematic. To Canadian nationalists of Gzowski’s era and ilk, the representative Canadian is no hewer of wood or carrier of water, no builder of bridges, roads and railways, no stormer of barricades or keeper of the peace, but a hobbled guest on a verdant fairway, eagerly apologizing for the pleasure of having his toes crushed. “That is what I like about you Canadians,” says Dr. Gunilla Dahl-Soot in Robertson Davies’s novel The Lyre of Orpheus, “you are so ready to admit fault. It is a fine, if dangerous, national characteristic. You are all ashamed.”

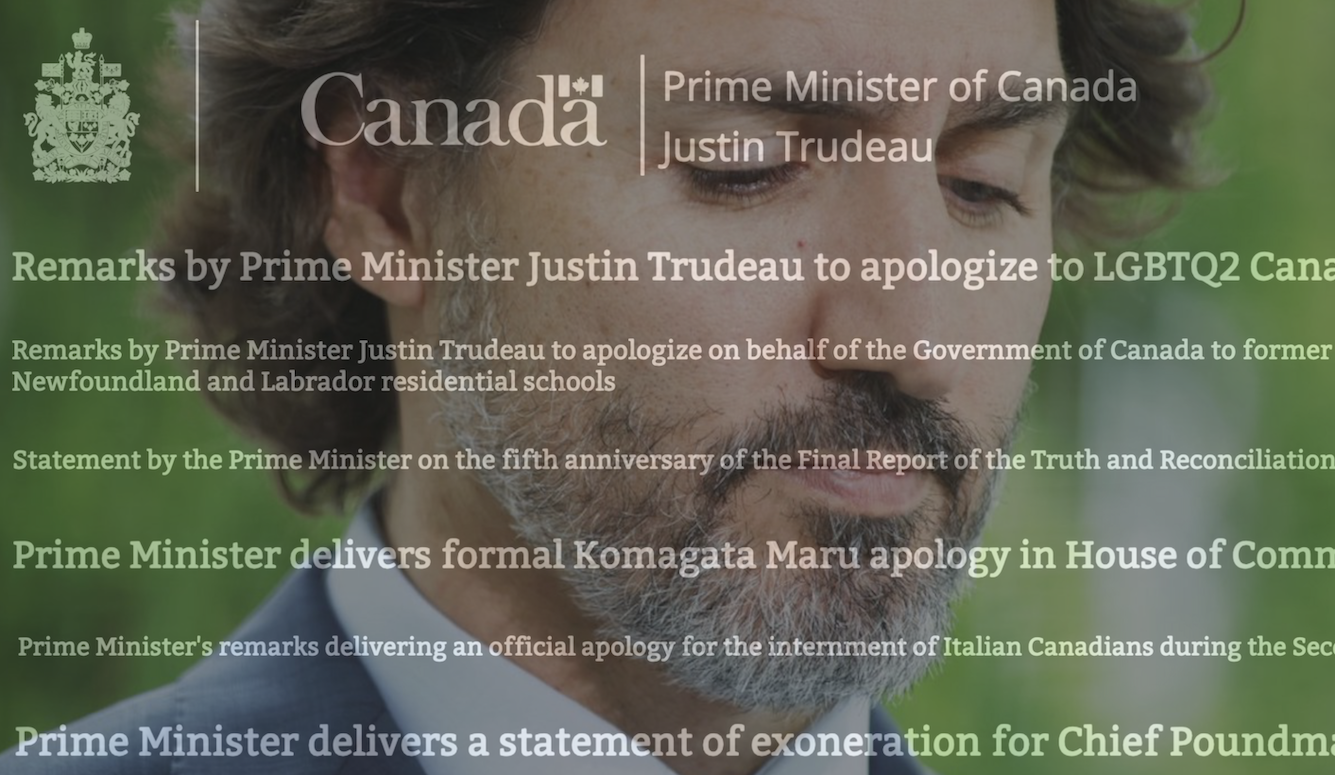

Over the past 200 years, notes Hungarian-born Canadian writer George Jonas, “we have been misled by science. Medicine became our hubris. Having learned to fix appendices, we thought we could fix history.” Today, in Canada, there is no clearer manifestation of this urge to renovate and repair the past than the vogue for apology. And no one has struck this posture of national self-abasement with quite the alacrity of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. Just months after taking office, he apologized for the Komagata Maru incident in 1914, in which a ship carrying Sikhs, Muslims, and Hindus was sent back to Calcutta, where 20 died in a riot. In 2017, he apologized to Indigenous residential-school survivors in Newfoundland and Labrador, and, just days later, to LGBT Canadians for decades of “state-sponsored, systemic oppression.” A year later, he apologized for the execution, in 1864, of six Tsilhqot’in chiefs over a road-building dispute, and for a government refusal, in June, 1939, to allow into the port of Halifax the MS St. Louis, an ocean liner carrying more than 900 Jews fleeing Nazi Germany. In March, 2019, he apologized for the inhumane manner in which Inuit in northern Canada were treated for tuberculosis in the mid-20th century. Two months later, he exonerated Chief Poundmaker of the Poundmaker Cree, apologizing for the Chief’s conviction for treason more than 130 years before. Still at it in the spring of 2021, Trudeau issued a formal apology in the House of Commons for the internment of Italian-Canadians during the Second World War, even though many, it was subsequently revealed, were indeed hardcore fascists, loyal to an enemy in a time of war. Two weeks later, he lowered the Canadian flag for five months to mark the discovery of the remains of Indigenous children who died at residential schools.

In the midst of this flurry of breathy performances, the BBC asked, with more than a touch of arch obviousness, whether the Canadian Prime Minister might not perhaps apologize too much. And yet, in Trudeau, we simply have the apotheosis of that habit of abject contrition celebrated by Gzowskian nationalists. Under his government, it has become fashionable, even necessary, to apologize, not just for egregious historical episodes or policies, but for the existence of Canada itself. In an interview with the New York Times, Trudeau witlessly described the country that had so favoured him through a lifetime of privilege as “post-national,” suggesting that Canada as we know it had somehow served its purpose, extended itself beyond any warrantable use. And recently, not to be outpaced by more current styles of denunciation, he described Canada, “in all our institutions,” as “built around a system of colonialism, of discrimination, of systemic racism.” When China, responding to criticism of its brutal treatment of Muslim Uyghurs, lashed out at Canada for committing “genocide” against its own Indigenous population and subjecting Asian-Canadians to “systemic racism,” Canada’s political class was in no position to quibble—as its prime minister had already muttered his agreement to the claim that he presided over a genocide state.

This note of cringing repentance now echoes in the pronouncements of all of our institutions. No matter how admired our country may remain internationally, no matter how ardently people around the world long to immigrate here for a chance at a better life, our presumptive leaders are eager to scorn Canada as a meagre and regrettable conceit. That the confessional mode they favour has become so prevalent confirms what Christopher Lasch long ago diagnosed as the strain of narcissism that courses through contemporary culture, lending ready appeal to all such facile gestures of self-reproach. There is, indeed, no cagier career move for any Canadian academic, journalist, bureaucrat, or politician these days than to repudiate Canada, and with feeling.

In his 2011 memoir, historian Tony Judt laments how the academic proliferation of various “identity studies” has had the effect of “negating the goals of a liberal education,” since it encourages students to obsess about themselves and the tribal affiliations that are presumed to define them. In this instance, as so often, he claims, “academic taste follows fashion”—the fashion in question being what he calls “communitarian solipsism.” And yet, communitarian solipsism is itself, of course, a peculiarly “academic taste,” the sort that, in time, trickles down to the public mind and, semi-digested and half-understood, acquires the heady burnish of fashion. The chain of causation that Judt identifies, in other words, often runs in precisely the opposite direction, from academy to culture. If this applies to the widespread determination to cast Canada as singularly irredeemable among nations, what is its precise source?

When Richard Rorty announced that literary criticism had displaced philosophy as the paradigmatic critical practice in bourgeois liberal democracies, he had in mind, not literary criticism in the traditional sense, but in the sense of “critique,” or “Theory,” which is widely assumed to be the adversary and opposite of traditional criticism. Rejecting the idea that literary works are, above all, objects of aesthetic attention, critique scans texts for hints of what Rita Felski calls those “sociohistorical fractures and traumas” they are alleged to suppress. Its fundamental quality, she says, “is that of ‘againstness,’ vindicating a desire to take a hammer … to the beliefs and attachments of others.” Drawn tantalizingly onward by “the lure of the negative,” she adds, even “the most chipper and cheerful of graduate students … will eventually master the protocols of professional pessimism.”

University of Chicago English professor Lisa Ruddick had that same sort of graduate student in mind when she recalled the many who have confided to her “unaccountable feelings of confusion, inhibition, and loss” in their study of literature, along with an “impression of deadness or meanness” in a field consumed by Theory, a chronic confusion of “sophistication with ruthlessness” that “glamorizes cruelty in the name of radical politics.” Indeed, the “progressive fervor of the humanities” more generally, she says, conceals a “second-order complex that is all about the thrill of destruction,” of burning through “whatever is small, tender … worthy of protection and cultivation,” flattening anything that might nourish us.

Theory directs its animus, above all, says Ruddick, at the very idea of selfhood, the presumed value of the inner life, and the attendant ideals of self-possession, self-regulation, and self-cultivation. Thus diminished, individuals are portrayed as interchangeable, “promoting the evacuation of selves into the group,” and undermining readers’ faith in loving attachments, in particular any assumption that home and family can sustain us in a troubled world. All such allegiances, according to Theory, are the mere leavings of “mainstream psychology,” symptoms of a “retrograde humanism” hopelessly “fraught with bourgeois ideology.” In his Seventh Letter, Plato insists that we are born, not simply for ourselves, but “partly for our parents, partly for our friends,” and “partly for our country.” If Ruddick’s conception of home likewise extends to one’s homeland, then perhaps we have here at least the beginnings of an answer to our question.

What by now counts as the ritual repudiation of Canada is most apparent in our institutions’ commitment to what is called “Indigenization,” the trappings of which call to mind the more pious exertions of compulsory chapel, ranging from drummings and smudgings to the incantatory liturgy of land-acknowledgement, routinely rehearsed before concerts, sporting events, and public talks, and broadcast even as part of morning announcements in our elementary schools.

I can think of no more telling example of this institutionalized repudiation than a poster distributed across the Saint Mary’s University campus in the spring of 2019, advertising the annual International Conference on Religion and Film. Featuring a grainy, black-and-white photo of the lighthouse at Peggy’s Cove, ensuring that the picturesque fishing village looked suitably dark and depraved, the poster announced that the conference would feature a keynote address and panels on the perfectly worthy topic of “Immigration and Indigeneity in religion and film,” while inviting submissions from both Indigenous and “settler” filmmakers. It described the port city of Halifax as occupying “a unique place in Canadian history as a point of ingress for settlers, entry for immigrants, refuge for loyalist Blacks, [and] exile for Maroons.”

The choice of “ingress” in this context is curious, since it’s not a word we often encounter. In Henry James’s The Bostonians, Basil Ransom’s attempt to speak to Verena Tarrant as she is about to deliver a public lecture from the Music Hall stage is thwarted by a “robust policeman … guarding the ingress.” And in E.M. Forster’s The Longest Journey, the narrator reports that, though Rickie Elliot does “not love the vulgar herd,” he knows that his own vulgarity would increase “if he forbade it ingress.” In both cases, “ingress” is used merely descriptively, referring to a point of entry, whether onto the Music Hall stage or into Rickie Elliot’s heart. And yet, the coordinators of the 2019 conference clearly had something else in mind, since they pointedly contrasted the permissible “entry” of immigrants with the prior and lamentable “ingress” of “settlers.”

We find a far more illuminating use of the term in T.C. Boyle’s The Road to Wellville, a novel that exploits the richly comic possibilities of the convergence of fledgling psychotherapy, fanatical health faddism, and general medical quackery in turn-of-the-century Battle Creek, Michigan. Among the novel’s cast of characters is the enigmatic Dr. Siegfried Spitzvogel, innovator of Die Handhabung Therapeutik, or, the manipulation of the womb, which requires digital penetration by the doctor at the womb’s “point of ingress.” Here, we have entry, to be sure, but of a much more sinister and intrusive kind. In the intended sense, “ingress,” for the organizers of the 2019 International Conference on Religion and Film, refers to entry that, whether of port or pudendum, constitutes a heinous violation.

This narrative of ingress informs the policy of “indigenization,” a commitment to which finds expression in what has become a highly stylized effort to delegitimize Canada. On this view, both Nova Scotia and Canada are fraudulent, “fake,” regrettable historical errors that we ought not merely denounce, but renounce. And yet, no ingress, no settlement; no settlement, no immigration, refuge, exile, or opportunity for those seeking to escape savage misery elsewhere for a shot at a better life in Canada.

Prominent individuals who lead the campaign at Saint Mary’s University to delegitimize Canada include those who have arrived recently from around the globe to lives of considerable privilege here. All, no doubt, are estimable, humane people. But, having been welcomed so generously to Canada, long after the hard work of settlement was done, and provided with the very peace, opportunity, and prosperity that prove so elusive elsewhere, what can possibly explain the appeal to them of this belligerent and rootless millenarianism?

In his new book, Last Best Hope: America in Crisis and Renewal, George Packer rehearses the views of “Four Americas”—competing, often warring, accounts of what best conveys the national character of the United States. He associates one of these with what he calls “Smart America,” which, given the obvious parallels in Canada, we might prefer to call Smart North America, that narrative endorsed by the professional classes, the educated, ambitious, hard-working, and sophisticated. Having “withdrawn from the national life” of their fellow citizens, the “sense of nation” among members of Smart North America is so “tenuous,” says Packer, that they can be said to have “lost the capacity and the need for a national identity.” They are not just “uneasy with,” but fail to see “the point of,” patriotism, in George Orwell’s sense of an instinct to love and defend a shared way of life. And yet, love of country, Packer insists, counts as “a persistent attachment … a source of meaning and togetherness,” a feeling that “can’t be wished out of existence,” and in the absence of which we fail to achieve anything worthwhile.

Packer’s book is one of scores published in recent years that attempt to diagnose the crisis in American national life and to propose means for its revival. A quarter of a century earlier, however, Lasch had already alerted his countrymen to the creeping malaise. In his final book, The Revolt of the Elites, he describes “the new elites,” or “knowledge classes,” as “far more cosmopolitan, or at least more restless and migratory, than their predecessors.” Given their ties to “an international culture of work and leisure,” he says, they lack “the continuity that derives from a sense of place,” are “devoid of any feelings of national identity or allegiance,” and “deeply indifferent to the prospect of national decline.” For them, love of country scarcely ranks “in their hierarchy of virtues,” since theirs is essentially “a tourist’s view of the world.”

Impressively credentialed, Lasch’s elites are alienated not just from place, but from the past. They find it difficult, he says, “to imagine a community, even a community of the intellect, that reaches into both past and future and is constituted by an awareness of intergenerational obligation.” If they aspire to community at all, it is as a “community of contemporaries,” consumed by the finicky obsessions of the present. Just as their loyalties lie far more with their counterparts in distant capitals than with their countrymen, so their intellectual commitments are not to ideas or principles, but trends. Still, in light of their enviable circumstances and prospects, what strikes Lasch most starkly about them is what he calls, borrowing from José Ortega y Gasset, their “radical ingratitude.”

If nothing else, the rhetoric of ingress furnishes us with an alternate view of the emblematic Canadian. Instead of the giddily penitent golfer favoured by the Gzowskian nationalist, we now have the rapacious “settler.” Whereas apology is the defining mode of the former, it is the reigning imperative of the latter. For Edith Wharton, an emblem amounts to “an example contagious,” by means of which a particular image and its battery of associations spread to, and take hold of, any receptive audience.

Ultimately, no doubt, we all choose our emblems. Here is mine—one that I hope will have particular resonance for my fellow Canadians as we observe Remembrance Day.

Many years ago, I was asked to house-sit for an older couple in the South End of Halifax. They had arranged to travel overseas, but had two dogs that needed to be cared for. The woman, Janet Kitz, was a Scot who had moved to Canada late in life, but who had become in relatively short order a respected local historian, particularly of the 1917 Halifax Explosion. Her husband, Leonard Kitz, had been the first (and I assume only) Jew ever elected Mayor of Halifax. They invited me for supper, to give me a tour of the house, introduce me to the dogs, show me where I’d be sleeping, and hand me the keys to the car, a temperamental standard-shift that I would need to drive the dogs to and from Point Pleasant Park for their daily walks.

After dessert, we talked over coffee, Mr. Kitz recalling past trips he had taken to Europe, including when he served with the Princess Louise Fusiliers in Italy and Holland during the Second World War. He recalled the day, in the early 1940s, when, in the wake of a series of Allied setbacks, he and his close friend Edward Arab, like him a young lawyer, decided to enlist together in the Canadian Army. Although Kitz survived the War, Arab—the son of immigrants who’d fled Ottoman-held Lebanon—was killed on October 25th, 1944 at the Dutch town of Bergen op Zoom during the Battle of the Scheldt Estuary. According to reports, he was leading troops forward against heavily fortified Nazi positions when they came under fire. Wounded in the leg, he was treated by medics, but pressed forward. His platoon continued to encounter fierce opposition, however, and he and six members of his regiment were killed in action.

Leonard Kitz managed to visit his friend’s grave just before the end of the War. But that evening, in his living room, he described returning many years later to lay flowers at, and take a photo of, the headstone for the Arab family back home. The impression that remains, however, is of two young men, both sons of immigrants, striding through the streets of Halifax, determined to sacrifice the comforts of home and the glittering promise of their young careers to fight together for a greater, and necessary, cause. The Jew and the Arab.

In The Revolt of the Elites, Lasch argues that democracy requires “a world of heroes” if the universal citizenship it promises is to avoid declining into “an empty formality.” Reserving his explicit admiration for the heroism of immigrants, workers, and families, whose “impersonal virtues” of “fortitude, workmanship, moral courage, honesty, and respect for adversaries” sustained them through routinely demanding and frequently desperate times, he is well aware of how naïve, even hokey, such expressions of honour strike Smart North America. For them, he knows, all “talk of heroes, exploits, glory, and disgrace is automatically suspect,” since the call for models of heroism “common to all” threatens the array of pluralisms they are determined to promote.

“How deep is citizenship?” asks anthropologist Lionel Tiger. Is it “a skin to be shed,” a “callus to sustain,” or a “sweet protection to enjoy?” In a memoir, he describes the Montreal of his youth as a city of enclaves, its turbulent ethnic politics animated by an “amalgam of frailty, perplexity, and irritation.” Meanwhile, the quality most lacking was what he describes as “symphonic joy,” an experience, an achievement, in which Smart North America appears to see little value.

According to Lasch, their ingratitude is enough to disqualify them from “the burden of leadership,” but there is little sign they will be leaving anytime soon. On their watch, we have seen how quickly a rare and enviable haven can threaten to fray and fall apart, just as we can more easily imagine how Canada might end—not with a bang, nor even so much as a whimper, but with something more like, say, an ingratiating chortle.