Politics

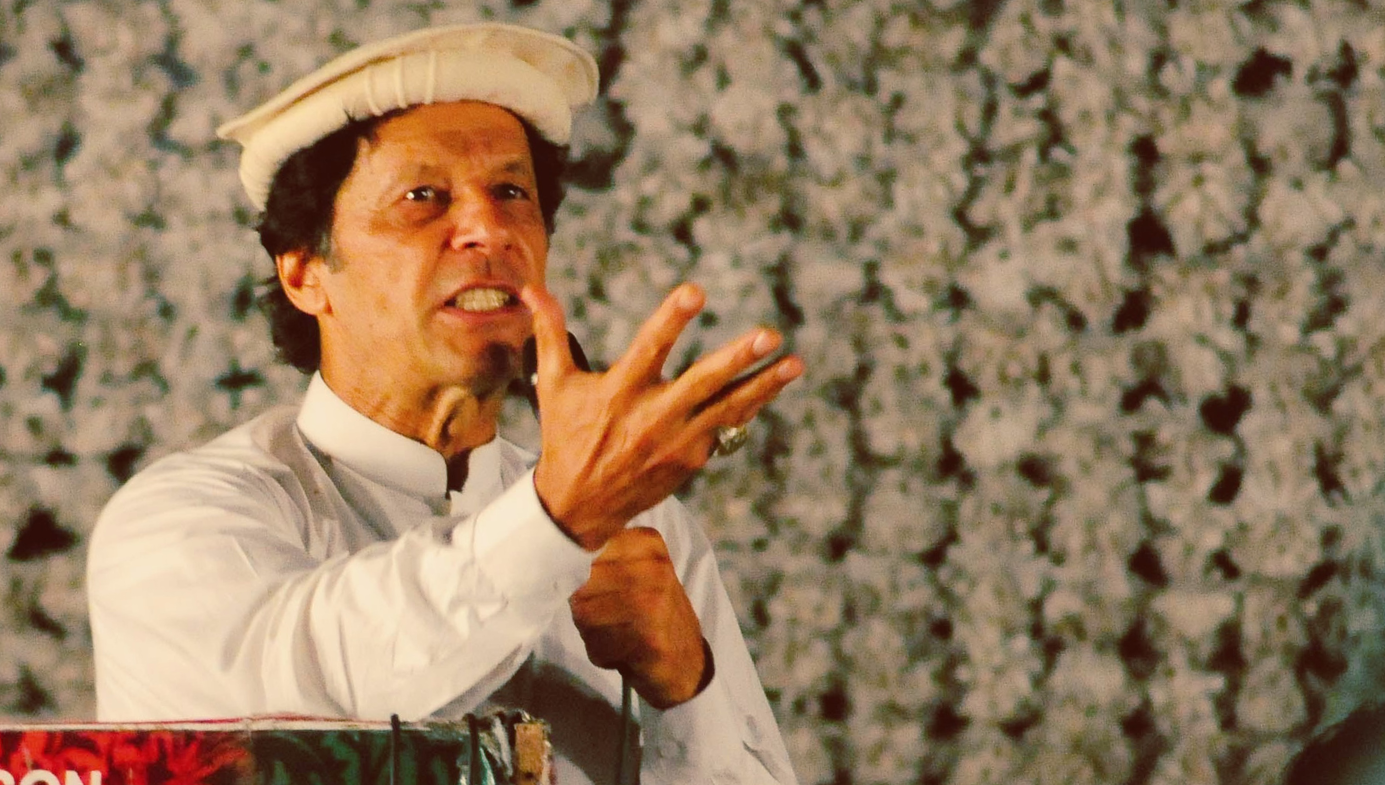

From Playboy Sports Star to Islamist Politician: The Strange Turn of Imran Khan

A further irony is that while Khan presses ahead with entrenching Islam in every nook and cranny of the polity and society, other Muslim-majority countries, including Saudi Arabia, are toning down the hard-line version of Islam that they have long promulgated.

The values trajectory of Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan is scarcely believable. Born into a well-to-do family in the new country of Pakistan, five years after the independence and partition of India, Khan received a prestigious education at the elite Aitchison College in Lahore and then at Oxford University. Like his older cousin, Majid Khan—who attended Cambridge—Khan was an outstanding cricketer. Both played county cricket in England and test cricket for Pakistan.

Though he hailed from the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, there was nothing remotely Islamic about his modus vivendi. Rather, in his many years in England, Khan led a brazenly modern, secular life that included partying and clubbing in London with an array of girlfriends who earned him the reputation of a playboy. “I never claimed to be an angel,” he has since admitted. “I am a humble sinner.”

Considered among the most eligible of bachelors, in 1995 he married Jemima Goldsmith, daughter of the billionaire tycoon Lord James Goldsmith and sister of future Conservative MP, Zac.

The marriage lasted nine years, after which Khan married a Pakistani woman, a union that quickly ended in an acrimonious divorce. He then married another Pakistani woman, and the trajectory of his belief system can be gauged from his choice of wives; the first was a modern European woman and the second was a fairly modern Pakistani. The third, however, is a strict, fully veiled, Muslim woman. “I did not catch a glimpse of my wife's face until after we were married,” he has explained. “I proposed to her without seeing her because she had never met me without her face being covered with a full veil.”

Khan’s cricketing career peaked when he captained Pakistan to victory in the 1992 World Cup. After he retired from cricket, he pursued a career in politics. An intelligent man possessed of enormous self-belief, he was passionate about improving the lot of his countrymen and -women. Distrustful of the existing parties which were dynastic and corrupt, he established his own political party in 1996, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) (Pakistan Movement for Justice). Upon entering the choppy waters of Pakistani politics, one factor has been constant—the centrality of Islam to his thinking, and to the PTI’s overarching goal of creating a theocratic welfare state.

Khan was eventually elected as an MP in 2002 and increasingly projected a strong Muslim identity; the playboy cricketing superstar had assuredly made the complete transition to a bona fide Islamist. (It is incongruous, however, and somewhat puzzling that he has not grown the bushy beard that is de rigueur for devout Muslim men.) A cynic might conclude that this abrupt “Islamic turn” is simply evidence of wanton opportunism and ambition—an attempt perhaps to deflect and defuse his notorious playboy lifestyle in England. There may be an element of truth to this but the extent of the turn is, nevertheless, astonishing.

In 2012, he pulled out of a conference in Delhi at which Salman Rushdie was also booked to speak, stating that he “could not even think of participating in any programme that included Salman Rushdie, who has caused immeasurable hurt to Muslims across the globe.” Rushdie responded by pointing out that “30 years ago Imran Khan was a fan at my 1982 Delhi lecture and 100 percent secular. Now my work ‘humiliates’ his ‘faith.’ Which is the real Imran?” He later added: “When Imran was a playboy in London, he was called ‘Im the dim.’ Imran may have been born again. He will have to be judged by this (the new Imran). Those of us who knew the young Imran don't remember him like this.”

In the 2018 general election, Khan’s party, with the support of the military, garnered the most number of seats. As prime minister, Khan has been relentless in his stress on Islam as the fulcrum of the Pakistani state and society. Forgetting his own secular upbringing, he proclaimed that Islam must be central to education and his government has promised to Islamise the syllabus. New textbooks for primary school students are imbued with Islamised content and his government intends to introduce a new Islam-heavy syllabus for middle school students and possibly for high school students as well.

Rubina Saigol, a Lahore-based educationist, correctly describes this development as the “madrassification” of public schools, and predicts that it will have serious ramifications. “The syllabus,” she says, “is likely to produce students with an Islamic conservative global outlook, who would view women as subservient souls who do not deserve freedom and independence.” Under Khan’s leadership, the Islamisation of education is not just limited to schools, it is being extended to universities. The government in Punjab province, for example, has made teaching of the Koran with translation compulsory for all university students. According to the provincial government, students will not be awarded degrees if they do not study the Koran.

Though antithetical to the true purpose of a rounded education, this policy programme has a certain political logic in a profoundly Islamic society. An analogy from chess can help us understand why. In the 1920s, the renowned Danish grandmaster Aron Nimzowitsch published his classic work, My System, which introduced the concept of “over-protection” of strategically strong points. If these are weakened, he argued, the whole position risks collapse. There is no doubt that Islam is a strategically important point in Pakistan’s body politic and Imran Khan has “overprotected” his allegiance. On this pivotal issue, there is not a scintilla of weakness in either his personal life or his ideological beliefs and political policy prescriptions.

The strange turn that Khan has taken certainly helped him forge a political career in Pakistan; arguably, it was a sine qua non for garnering the support sufficient to become prime minister. But it has not helped—and will not help—improve the lot of the masses in his country as he so passionately desires. To the contrary, ample evidence shows that Muslim-majority countries reside in the lower reaches of global socio-economic indicators—with Pakistan near the very bottom—suggesting that Islam acts as a barrier to progress and development, not an accelerant.

A further irony is that while Khan presses ahead with entrenching Islam in every nook and cranny of the polity and society, other Muslim-majority countries, including Saudi Arabia, are toning down the hard-line version of Islam that they have long promulgated. The authors of the Abu Dhabi Declaration of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) on Science and Technology in June 2021 point to this. Paragraph six makes this unambiguous proclamation: “We are aware that knowledge and critical thinking[,] of which science, technology and innovation are the most visible symbols, are the principle drivers of change, not just in terms of accelerating the pace of economic development, [and] improving productivity and competitiveness, but in all human endeavors.” Paragraph seven elaborates that the “promotion of science, technology and innovation is crucial for addressing the contemporary challenges of development, poverty eradication, environment, education for all, climate change, human health, and energy and water resources.”

This stress on science, technology, and innovation is absolutely correct. However, it is indubitably the case that for their implementation, and for the attainment of the socio-economic goals desired, the edicts of Islam must be firmly confined to the private sphere, just as religion is in the most advanced countries. This will present an enormous challenge to OIC countries (though Bangladesh prime minister Sheikh Hasina recently announced that following attacks on Hindus, the country will revert to its 1972 secular constitution). But it is safe to aver that the present trajectory of Pakistan under Imran Khan’s leadership will make their realisation there well-nigh impossible.