LGBT

The Implosion of Boston’s Pride Parade Is a Sign of Things to Come

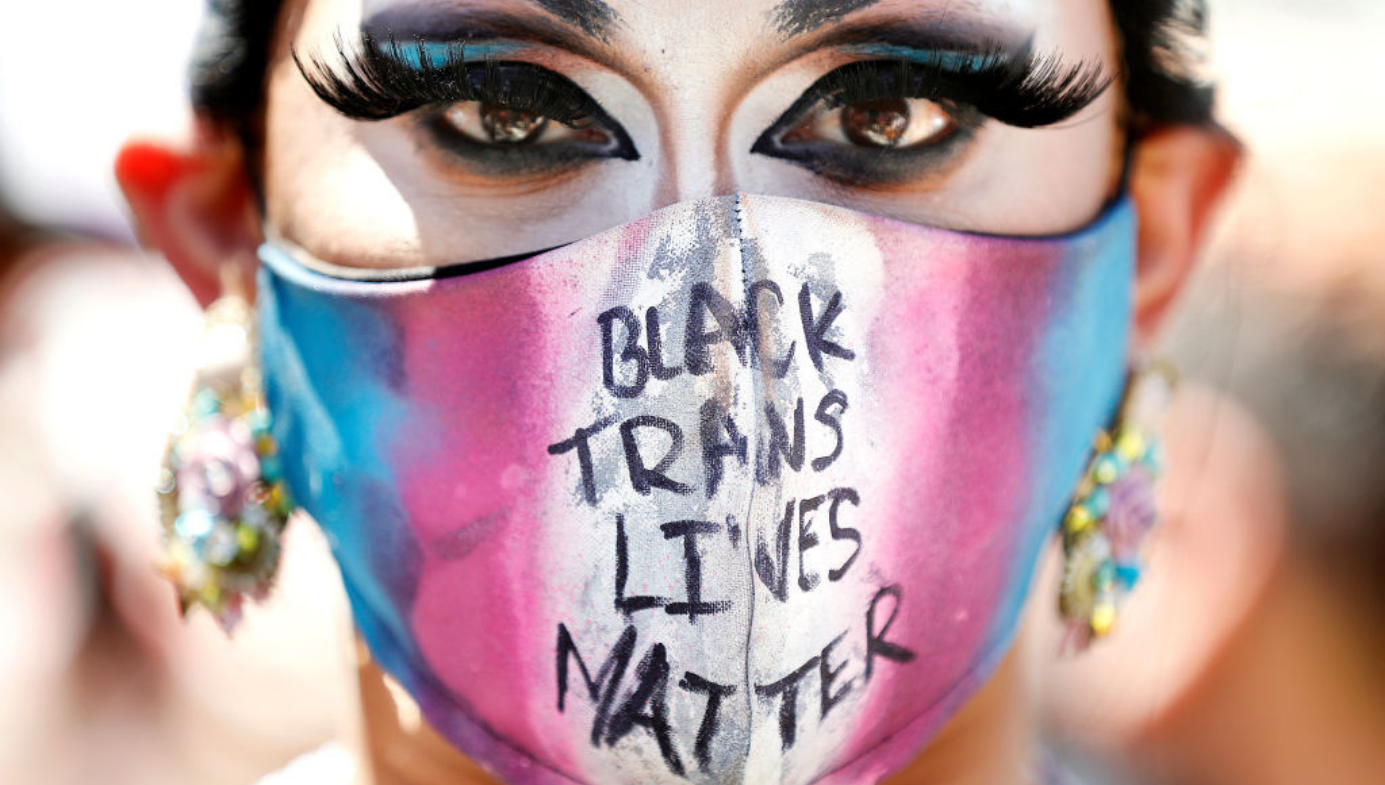

Pride 4 The People and its allies were scathing, accusing board members of preferring to shut down the organization rather than include black and trans people.

Boston Pride is one of the oldest gay-rights organizations in the United States, with its first parade having taken place in 1971. Last year would have marked the 50th parade, but the event was cancelled due to the pandemic. This year’s events also didn’t materialize, but not entirely because of COVID-19. Rather, Boston Pride celebrated a half-century-plus of existence by collapsing into social panic and cancelling itself. I mean this literally: Boston Pride no longer exists. The organization was dissolved from within in July, when its board of directors released a statement that read, in part:

It is clear to us that our community needs and wants change without the involvement of Boston Pride. We have heard the concerns of the QTBIPOC [Queer, Trans, Black, Indigenous, and People of Color] community and others. We care too much to stand in the way. Therefore, Boston Pride is dissolving. There will be no further events or programming planned, and the board is taking steps to close down the organization. We know many people care about Pride in Boston, and we encourage them to continue the work. By making the decision to close down, we hope new leaders will emerge from the community to lead the Pride movement in Boston.

And what are the QTBIPOC community’s “concerns.” Well, it’s a long, surreal, and tragicomic story. And to tell it coherently, I’ll have to start with events that took place more than six years ago.

The seeds of Boston Pride’s self-destruction were sown in June 2015—ironically, just weeks before the US Supreme Court released its decision in the case of Obergefell v. Hodges, which required all states to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples. (Massachusetts had already legalized gay marriage in 2004.) On June 13th, about a dozen Black Lives Matter activists managed to halt Boston’s annual Pride parade for 11 minutes—one minute for each transgender person that had been murdered that year, they explained.

The activists released a statement, declaring that:

We live in a society that has declared war on Black people, women, immigrants, trans people, poor people, and—at the intersection of all that—trans women of color. It is the duty of the entire LGBTQ community to stand united and prove that all of our lives matter. YOU’VE GOT MARRIAGE—WHAT DO WE HAVE??

They also issued a long list of demands, including the following:

We demand a Pride board as diverse as our community, and not solely comprised of wealthy white capitalist gays and lesbians.

We demand our community come out publicly against holding the 2024 Olympics in Boston. The Olympics will bring unprecedented gentrification, surveillance, cutting of social services, and punitive policing to our city.

We demand that Boston Pride remembers that Pride started as a riot led by trans and gender non-conforming people of color!

(BLM also complained that the parade had been held in the downtown area of Boston, a location that “purposely excludes communities of color and perpetuates the idea that communities of color are somehow more homophobic than white people.” Putting aside poll data showing that American whites are, on average, less homophobic than their black counterparts, it seems strange to suggest that this had any bearing on the question of where a Pride parade would be held: In Boston, as in other cities, downtown areas are the traditional venue for this kind of civic event because they are centrally located.)

Things got worse in 2016, when Boston Pride chose a police officer, Anthony Imperioso, as parade marshal. Activists circulated a “No Police Marshals at Boston Pride” petition. They found the selection of Imperioso to be particularly objectionable, as he’d previously expressed unfavorable opinions about BLM protesters shutting down a major Boston highway during rush hour in January 2015. On Facebook, he called them “very unpatriotic anti-American trash” with a “left-wing Marxist agenda.” Boston Pride withdrew his marshalship and apologized.

In 2018, another sit-in disrupted the parade, this time under the banner of a group called “No Justice No Pride.” Its members were upset with the involvement of corporate sponsors who had also donated to Republican politicians; the presence of LGBT police officers at the parade; and an invitation that had been extended to the Israeli consulate in Boston, on the claim that Israel used LGBTQ advocacy as a means “to distract from their human rights abuses towards the Palestinian people, [including] apartheid, and ethnic cleansing.” Activists were further incensed when Boston Pride added a US Army veteran and former secretary of the Massachusetts Log Cabin Republicans (the LGBT wing of the GOP) to its board. In short, the activists resented the idea of a Pride parade that included any constituency, LGBT or otherwise, connected to Republican politics, law enforcement, the military, or Israel.

But all of these controversies paled compared to the one that developed in 2020, following the death of George Floyd in May, when Boston Pride released a pro-BLM statement that had been watered down from the original draft that had been prepared by the group’s communications team. These revisions included:

- Replacing two instances of “police violence” with “violence committed by some members of the law enforcement community” and “brutal acts committed by people wearing police badges and uniforms”

- Removing a call to donate money to “anti-racist organizations”

- Removing a call to demilitarize the police

- Replacing “Oppressions are interlocked, no one is free until we are all free. #blacklivesmatter” with “No One Is Free Until We Are All Free. We are #BostonPride #WickedProud”

The board’s longtime president, Linda DeMarco, explained that the language originally suggested by the communications team had been “a little too strong against the police, and we have a very good relationship with the Boston police.” When board members refused to resign en masse so that they could be replaced by a more “inclusive” slate, about 80 percent of Pride’s volunteers resigned in protest, along with the chairs of the Black Pride and Latinx Pride subcommittees. In a new statement released under the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag, the board asked for forgiveness and promised to hold themselves accountable:

[We have] heard the voices of concern from members of the community regarding a previous statement posted on our website related to the recent atrocious events of the murders of Black and Brown people at the hands of police officers in so many places across this country. We deeply apologize for the hurt and pain we caused by our shortcomings. We pledge to hold ourselves accountable now and in the future. We acknowledge that we need to do more as a social justice organization to not only communicate our outrage, horror and intolerance of these acts of police violence, but also to take substantive action to better address racism and white privilege within Boston Pride, the LGBTQ+ community and society at large.

But activists weren’t satisfied, and the board was pressured to make more concessions—including the shelving of nearly all virtual Pride events in favor of “Events that Support the Black and Brown Community.” But by this time, it seemed no gesture of apology or appeasement would suffice. And some former volunteers set up a rival group called Pride 4 The People as a vehicle to organize boycotts. A group of transgender activists also started a separate group called Trans Resistance MA to “advocat[e] for the safety, joy, and liberation of TQBIPOC” (this term being identical to “QTBIPOC,” except with the Q and T pointedly reversed). Together, these groups put on a “Trans Resistance March and Vigil for Black Trans Lives” as an alternative to the cancelled Pride parade. But in contrast to the celebratory, upbeat mood that generally characterizes Pride, the March and Vigil were somber and somewhat morbid.

The organizers even issued a set of special instructions for any “white person planning to attend the event.” One commenter advised that “white queers [should] pretend that you are attending a funeral for a friend of a friend of a friend. You want to support the friends there, but you didn’t really know the person who passed. Would you shove yourself to the front of the room and sob and make everyone else uncomfortable? I sure hope not. That funeral isn’t for you, it’s for the people who are seriously hurting and you’re there to show support.” Sounds fun, no?

By mid-June, 2020, activists were insisting that there was no other solution except for the Pride board to completely surrender control of the organization to their activist critics. They blasted the board for its “white-centeredness” and for being “trans-exclusionary.” (At the time, the board had six members—four white and two Latino, one of whom was transgender, but no black members.) In response, board members announced a planned “transformation” of Boston Pride.

As a last-ditch strategy to maintain their positions, board members hired two diversity consultants: Judah-Abijah Dorrington and La Verne R. Saunders. Their consultancy self-describes as “specializ[ing] in transforming organizations to honor and operationalize their social justice missions from theory to application to practice.” The firm’s services also include “the restoration of the good, inherent nature of human beings by facilitating transformation in individuals, groups, organizations and governments as they heal from the effects of traumatizing oppressions.”

After six months under the tutelage of Dorrington and Saunders, Boston Pride announced the details of its grand transformation, which included the declaration that it now would be prioritizing “the representation of Queer, Transgender/Gender non-binary, Black, Latinx, Indigenous and other people of color.” Boston Pride also announced new positions on its board, as well as new committees to staff. Pride 4 The People and Trans Resistance MA, however, dismissed this as a “faux-transformation,” and instructed supporters to boycott the new board seats. As a Boston Globe writer noted, this led to a bizarre standoff that went on for months: On the one hand, activists said they wouldn’t participate in the board’s allegedly insincere reform effort until these same activists occupied a majority of the board positions. On the other hand, they couldn’t occupy any board positions—let alone a majority—until they ended the boycott.

All of this, of course, was going on during a pandemic—a pandemic that caused Boston Pride to announce, in February 2021, that there would once again be no summer parade, while leaving open the possibility of a replacement event in the fall, “if all conditions are in place for such events.” (The year’s theme was later selected as “The Rainbow After the Storm, [which] reflects on the past year being one of major pain, sorrow, and upheaval in our community and the world as a whole. It represents an opportunity to come together again, and support each other in healing from the events of the past year, and in committing to continuing to work as a community toward acceptance, justice, and understanding.”) But the anti-board coalition doubled down on its boycott, instructing LGBT community members to skip all 2021 Boston Pride events and withhold donations unless the board resigned and control of the organization was ceded to activists.

On April 16th, Boston Pride announced the appointment of seven (non-boycotting) community members to its new Transformation Advisory Committee (TAC). A week later, the police officer who killed George Floyd, Derek Chauvin, was convicted of murder. In apparent atonement for its perceived sins following Floyd’s death, Boston Pride’s board released a statement that systematically name-checked every possible activist slogan and talking point:

Our thoughts and hearts are with the family and friends of George Floyd, who would be alive today but for the murderous actions of Officer Derek Chauvin. We acknowledge and understand that his actions are a manifestation of a deeper problem rooted in over 400 years of systemic racism, white supremacy and social justice inequity … One single conviction for police murder is not enough … Police violence and murder disproportionately targets Black, Brown, Indigenous and other people of color, especially Black Transgender Women … Our hope is that police accountability rooted in systemic racism will become the norm rather than the exception … We stand in solidarity with others in the struggle to extend police accountability to include QTBIPOC … We will continue our commitment to hold ourselves accountable, and be held accountable, as we work in partnership with QTBIPOC communities to displace white supremacy and dismantle systemic racism. We will be active participants in creating and maintaining a just and equitable world for everyone in which #BlackLivesMatter and #BlackTransLivesMatter. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.

They also included this telling postscript:

This statement was a collaboration of the Boston Pride Board and Staff, Boston Pride’s Communication Team, the new Transformation Advisory Committee (TAC), and DAIE consultants Dorrington & Saunders LLC. These groups are working together in the organization during its ongoing transformation process, to ensure that Boston Pride’s intentions and rationale are in alignment and in the best interests of the QTBIPOC/LGBTQ+ community.

In other words, the memo represented a complete ideological surrender to board critics who’d sought to reimagine Pride as an explicitly anti-racist social-justice organization that prioritizes the demands of trans people—black transwomen, in particular—over other members of the LGBT community. The board members also took the extra step of humiliating themselves by noting that they were under the close oversight of minders who might slap them down if they went off-script.

Not surprisingly, the 2021 iteration of Pride month was a dud in Boston, with almost all the June events being either cancelled or boycotted. The only major event to take place was the second Trans Resistance March and Vigil for Black Trans Lives. On June 9th, amidst this depressing climate of conflict and failure, Linda DeMarco told the Boston Globe that she planned to resign as board president. She added that her resignation was “a little accelerated now because I think the boycott is really hurting the community.”

But far from being a victory for activists, the move turned out to be a defeat for everyone—because rather than continue with a coerced process of “transformation,” Boston Pride’s board simply announced its dissolution.

Pride 4 The People and its allies were scathing, accusing board members of preferring to shut down the organization rather than include black and trans people. That explanation seems unlikely, given the servile posture the board had assumed toward these same groups. But the truth is that no one knows exactly why board members took the route they did. Whatever their reasons, though, Boston Pride is no more, New England’s largest LGBT parade is in limbo, and whatever leadership emerges to fill the void will, in all likelihood, assume a posture that is more radical, more shrill, and more off-putting to the general public.

In any political movement, activists face an existential question: what do we do if we win? Most never have to answer that question, because winning is hard, especially when you have lofty goals—or, in some cases, nebulous or unattainable ones—Save the Planet! Demand Justice Now! But in the case of gay rights, the goals from the beginning were pretty specific, and the legal victories achieved in the last 20 years have been swift and comprehensive. In the United States, landmark Supreme Court cases have struck down statutes criminalizing homosexuality, and established equal rights in marriage, employment, and military service. Beyond the legal victories, the movement has also won broad popular support. In 1996, just 25 years ago, only 27 percent of Americans supported same-sex marriage rights. Today, that figure is a record 70 percent.

Since Obergefell, Pride organizations in many parts of North America have been flush with cash and political influence, but not quite sure what to do with it. In Boston, as in other cities, Pride has fractured into several camps. One is made up of those who are happy to see Pride become a blander, more corporate, mass participation institution within America’s ever-expanding civic calendar. The second major bloc is made up of those who seek radicalism for its own sake, and who are desperate to rekindle what they see as the revolutionary origins of Pride. And so if gay rights is no longer radical, they insist, the LGBT movement must pour its energy and resources into causes that offer the possibility of militant politics—such as radical gender movements, the erasure of biological sex, anti-capitalism, demonization of Israel, extreme forms of “anti-racism,” pacifism, and police abolition. Even gays and lesbians, now seen as the “privileged” elite of the LGBT population, are the subject of suspicion, and even animosity.

This affected radicalism is totally unmoored from the reality that the LGBT movement has achieved nearly all of its goals. Even in regard to the nominally radical causes these activists tend to embrace, the conceit of being brave and revolutionary is quite thin, since it turns out that many of these same causes are actively supported by progressive politicians, academics, major cultural institutions, Hollywood, and even “woke” corporations. Activists who tell themselves that they’re raging against the machine have, in many cases, become the machine.

As a gay American, I celebrate what the gay rights movement won for me and millions of my compatriots. But I mourn what it has become. The good news about Boston Pride dying from within is that its death is really a symptom of victory, not defeat: We simply don’t need the movement anymore in order to live full and equal lives in society. The bad news is that its death throes and radical rebirth will generate more farces of the sort Boston has been subjected to for six years and counting.