Review

Bitter Lessons from Afghanistan

The decision to withdraw from Afghanistan returns those nations willing to fight evil to their couches, where they can sigh in safety.

A review of Can Intervention Work? by Rory Stewart and Gerald Knaus; W.W. Norton, 272 pages (August 2011)

The American War in Afghanistan: A History by Carter Malkasian; OUP, 576 pages (July 2021)

The Afghanistan Papers: A Secret History of the War by Craig Whitlock; Simon and Schuster, 368 pages (August 2021)

The Long War by David Loyn. St Martin’s Press, 464 pages (September 2021)

In his 2011 reflection on intervention, Rory Stewart offers a composite picture of a typical foreign adviser to Afghanistan before the Taliban swept back into Kabul’s Arg Palace: "James" is young, highly credentialed academically in the UK and the US, hard working, optimistic, with “no 19th century prejudices about race, or women, or class … a great improvement (in these senses) on his colonial equivalent.” But unlike that equivalent, who might have been trained in native languages over two years and remained in various posts abroad for 16 years or more, "James" has “little knowledge of Afghan archaeology, anthropology, geography, history, language, literature or theology.” He is, however, an expert in “fields that hardly existed in the 1950s, and which are hardly household names today: governance, gender, conflict resolution, civil society and public administration.” He might be there for a year—two at a stretch. Ever after, these years would be a notable mention in his CV, like a medal for bravery (and working in Kabul in the Taliban interregnum did indeed take courage).

This observation appears in a book Stewart co-wrote a decade before the US and other forces evacuated pell-mell in August, and it hangs over the Western—mainly American—experience in Afghanistan. At 48, Rory Stewart has been a British Army officer, a diplomat in Afghanistan, a district official in Iraq, head of Harvard’s Carr Centre on Human Rights, Conservative MP for Penrith, cabinet minister at the Department of International Development, and a candidate for the Mayoralty of London and for the leadership of the Conservative Party. Which is to say that he has amassed more political and foreign policy experience than most analysts and pundits.

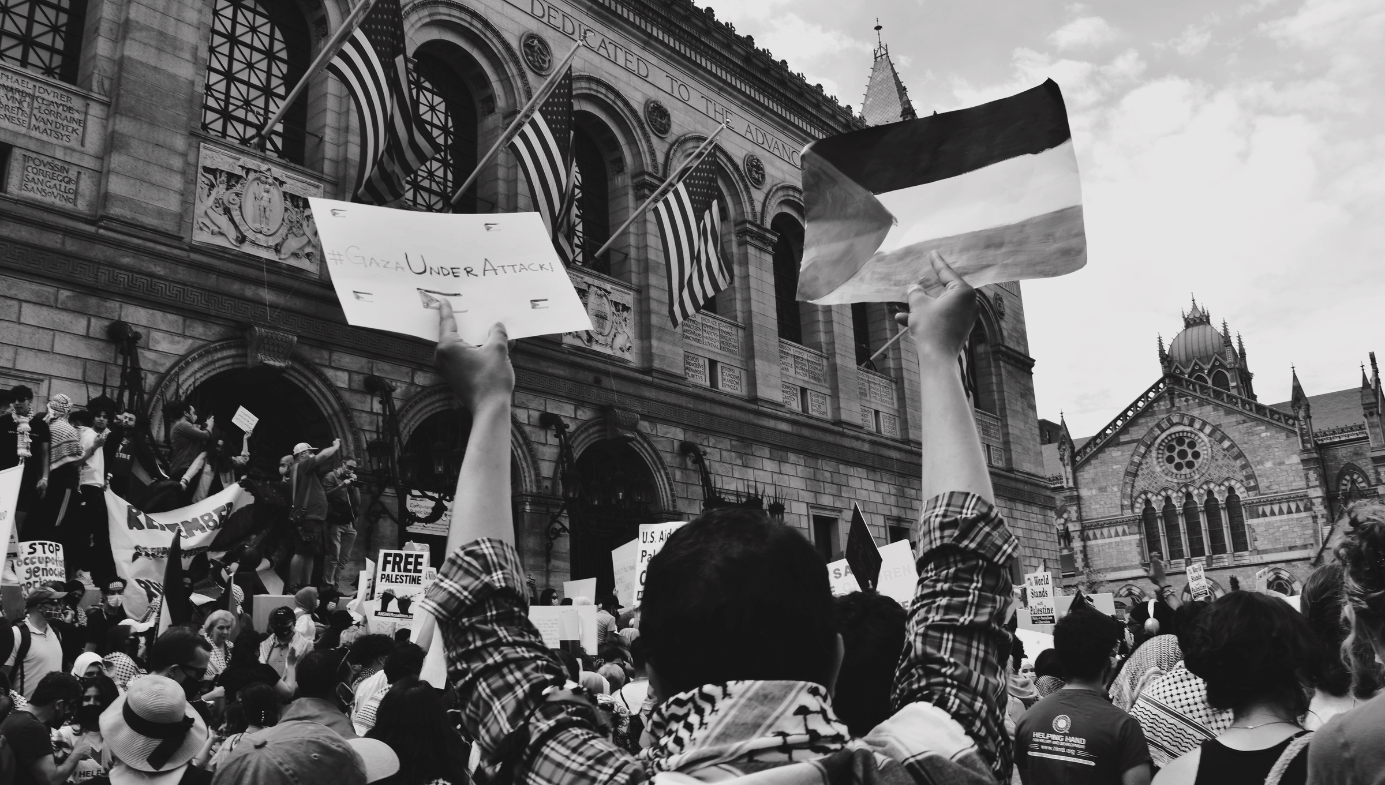

Can Intervention Work? is composed of two essays, one from Stewart and the other by the researcher and founder of the European Stability Initiative, Gerald Knaus. Together, they anticipate the collapse and chaos of the past two years, which has galvanised those who yearn for the end of US hegemony and the decline of the West. The American retreat from Afghanistan has already been the cause of rejoicing in Beijing and Moscow, and a more discreet schadenfreude in much of Europe, especially—but not exclusively—on the Left.

The most depressing element is the huge mendacity on the part of generals, politicians, and presidents who reassured their electorates that the war on terror was going just fine. The Americans were way ahead on this, but not alone. Western politicians knew how bad conditions were in Afghanistan, how corrupt the government was at every level, and that there were credible allegations that Karzai’s people had stuffed ballot boxes to ensure re-election in 2009. Nevertheless, they continued to peddle the fiction that democracy, civil society, stability, and prosperity were all within reach. As Stewart knew better than most foreigners, insofar as these aspirations existed, they are held among a thin layer of professional Afghan men and women, mostly in Kabul, many of whom are Western educated.

The American defeat in Afghanistan is frequently compared to that in Southeast Asia, and Stewart refers to former US Defense Secretary Robert S McNamara's 1995 memoir, In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam. McNamara, a rare penitent among the US officials who oversaw that war, does not believe American failure can be blamed on the tenacity of the Vietcong or anti-war sentiment at home. America failed because, he wrote, “We viewed the people and leaders of South Vietnam in terms of our own experience. We do not have the God-given right to shape every nation in our own image or as we choose.” These words, written in some anguish, are a call to the deepest reflection in governing, and would-be governing circles, after Kabul.

Knaus expands upon this critique of liberal imperialism, a view he and Stewart once shared. While working in Bosnia, he began to support Western military intervention—he was, he writes, “partaking in the growing liberal imperialist sentiment, arguing strongly that the international community needed to take a more proactive role in building the institutions of a functioning Bosnian state.” Those who favoured intervention—at times polls showed it was a majority, in the US or the UK—seldom thought of it as “God given.” Rather, they believed it to be a failure on the part of politicians and the military to grasp the extent of carnage being visited upon helpless communities. But Knaus now dismisses liberal imperialism as only rarely successful. The less comfortable lessons he draws from Bosnia are that “to end mass atrocities, it may be necessary to deal with evil, accept limited goals, and bide our time. Not all good things go together … the answer from the last two decades is that where we believe any price is worth paying, and that failure is not an option, we are likely to fail. Where we tread carefully, and fear the consequences of our mistakes, there is a chance.”

That Can Intervention Work? should, after a decade, find its predictions and warnings so amply fulfilled must bring a grim satisfaction to its authors, and a sense of despair to those still sympathetic to the case for humanitarian intervention. Nevertheless, there appears to be a gathering consensus. Two of the most recent books about Afghanistan are by careful writers who are knowledgeable about the country, its people, and its present rulers—and on the basis of experience, both arrive at the same conclusions in 2021 as Stewart and Knaus did in 2011.

Carter Malkasian has a doctorate of military history from Oxford, and conducted research in Iraq, followed by longer stints of hands-on work in various Afghan provinces advising successive commanders. Unusually, he spoke Pashto—the second most widely spoken language after Dari—and preferred to operate without elaborate safety precautions. His book is a history, beginning with President Jimmy Carter’s decision—pushed by his National Security Adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski, but opposed by his Secretary of State, Cyrus Vance—to back the fundamentalist mujahideen against a communist-inclined government. This was just before the Soviets authorised an invasion in 1979. Back then, anti-communism was everything. After 9/11, anti-jihadism was everything.

Malkasian’s scholarly approach can be slow, but he knows the warp and woof of Afghan society better than any of these writers. He appreciates, too, the pressures on commanders at every level when faced with a ruthless, apparently unconquerable enemy. He makes clear that successive peace opportunities were passed up by the US. The Taliban wouldn't come to the table unless it was from a position of strength, and nor would the Americans, until the pretence that winning was possible had been hollowed out (though rarely openly acknowledged) and nothing was left except to save what face they could.

The huge bombing campaigns used by successive generals killed plenty of terrorists, but they also killed civilians in considerable numbers. As Malkasian and the other authors stress, for most troops on the ground it was hard to know who was an enemy and who was an ally. Nevertheless, non-combatant casualties cost the Western coalition a great deal of support from Afghanis who had not been pro-Taliban. The Taliban had been brutal and had forced women into a state of virtual imprisonment. Yet the group came to be seen as a source of security and peace—they were Afghans, not foreigners; and their morals and behaviour chimed, at least in part, with those of the majority of Afghans who lived in villages and small towns.

The commitment of troops, advisers, and materiel, and the successive “surges” of troops called for by the generals, were undercut by politics. This was true in Washington, where exasperation grew as a decisive victory was thwarted by an enemy operating from a safe haven in Pakistan on the country’s southern border. It was even more true in Kabul. At his accession in 2002, President Hamid Karzai enjoyed worldwide plaudits. He'd opposed communism and the Taliban, spoke good English with a courtly demeanour, and had roots in the Pashtun tribal culture. But as the war turned against the foreign armies, and the mainly US efforts—with huge expenditure—to train an effective army and police force failed to produce effective organisations (the police routinely extorted bribes, often with violence), Karzai became less complaisant with the occupying forces. Sensing his increasing isolation and loss of popular support, he resigned from the presidency in 2014.

David Loyn was a BBC correspondent who dedicated much of his life to understanding Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India, with conducted several interviews with Taliban leaders. He and his camera team were the only journalists to record the Taliban’s victorious entry to Kabul the first time they took over. He covered much of Karzai’s period in office, making a confused political scene as clear as he could. In the last two years in Afghanistan, he was an adviser on communications to Ashraf Ghani, who became president after Karzai’s resignation. Ghani fled with his family a day before the Taliban took the Arg palace, and has since been accused of taking large sums of money with him. He has vehemently denied this accusation, saying he left to avoid a bloodbath, and has been variously described as landing in Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and more recently in the United Arab Emirates.

Loyn, an admirer, believes that Ghani was not personally corrupt and knows how constrained his choices were, but does not duck recording a catalogue of failures. These included the deliberate weakening of the regional governors, an inability to build political support and a flaccid and self defeating response to the chance of developing a peace process with the Taliban. One of the most intellectually able of leaders anywhere in the area, his lack of a feel for politics in a continually violent surrounding and his absence from Afghanistan for much of his professional life hobbled him and his administration.

The Americans simply assumed that, given freedom from the Taliban, order would re-emerge of its own accord, since it was in their interests to cooperate and build a functioning society and economy. But what—or who—emerged of their own accord were the warlords, who had opposed the Taliban. These were cruel and despotic men, who quickly became skilled in enriching themselves from the billions of dollars pouring into the country so fast it could not be spent. “Twenty of the first thirty-four of the provincial governors appointed after the Taliban were former warlords,” Loyn writes. “Forty warlords took their seats in the first Afghan parliament in 2005 (along with twenty-four leaders of criminal gangs, and traffickers). One of the first acts of the new parliament was to pass a general amnesty for past war crimes … the level of democratic failure this revealed was illustrated by a poll recording 94 percent support for war crime trials. The political system that emerged did not represent the nation.”

Loyn argues that, during both Karzai’s and Ghani’s periods in office, prosecution of the war was hampered by conflicting realist and idealist impulses in the American capital: “Hard-headed opposition to nation-building ran counter to a mood of wanting to spread democracy and leave the world a better place.” These arguments were taking place as similar tussles went on over Iraq—in neither case were new nations built in the manner the phrase intended.

Despite many thousands of deaths and the depletion of the resources of a very poor country, a regime has returned to Afghanistan that will set back women’s education and participation in wider society, that will retard or reverse advances in health, modernisation of infrastructure, and communication, and that will likely ally itself with the authoritarian powers and harbour terrorist groups. This is all quite bad enough. But the consistent lying of the US administrations under the presidencies of George W Bush and Barack Obama—differing in much, united in this—was shameful, and has helped destroy public support for such actions in the West. Craig Whitlock’s Afghan Papers may be jerky as a narrative, but it is still the place to go to see the sheer scope of political mendacity.

Whitlock, a reporter for the Washington Post covering security issues and the Pentagon, has assembled troves of material from the files of the Special Investigator for Afghan Reconstruction, the copious memos of the former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld (known as “snowflakes”), and from oral testimony to the US Army Operational Leadership Program and the University of Virginia Oral History Program. In these programs, military and civilian personnel with experience in the country spoke freely about their views on the war following their service, and their candid statements often contrast violently with their public positions.

These men were often at the top of the political tree. Robert Gates, who took over as Defense Secretary from Rumsfeld in 2006, thought building democracy in Afghanistan was a “pipe dream” but from the moment he took the job (until 2011), he followed his president’s lead in assuring the public that this was an achievable goal. Generals David Petraeus and Stanley McChrystal, two of the most outstanding officers of their generation, had grave doubts about the ability to prevail militarily and still graver doubts about building anything like a democratic state. But when in command, they dutifully bought into the line. “We will win,” Petraeus boldly declared in June 2010, upon taking over as supreme commander in Afghanistan. When a wedding party, and later a gathering of some 90 children, were mistakenly bombed, both were denied. When, under Obama, Leon Panetta took over at the Pentagon, he too hid doubts under the confident announcement that “Al Qaeda is finished”—repeating what George W Bush had said years before.

Trump inherited a war the goals of which he thought were crazy, attainable or not. Yet in his first speech on it, he fell back on the categorical “We will win.” When the generals arranged a briefing for him to tell him something of the reality, he grew angry, calling them “dopes and babies”; a second briefing left him blaming Obama for setbacks. Campaigns to turn Afghan farmers away from growing opium—the output grew so high, that it accounted for 80–90 percent of world consumption—were such complete failures that output went up more sharply when the programs were running. Denied a success which might have added lustre to his presidency, Trump abruptly announced a complete pull-out—a decision which President Joe Biden, long the most sceptical among senior US politicians of the war’s utility, gladly inherited and duly executed by September 11th, 2021.

In taking the decisions they did, Trump and Biden have been held by much international opinion to confirm the decline of America. The “world’s policeman,” was granted by Madeleine Albright, Secretary of State 1997–2001, the right to intervene in wars, coups, and potential threats the world over. In an interview with Matt Lauer in 1998, she named America “the indispensable nation,” endowed with the inalienable right to decide where and how it would intervene. The books reviewed here differ in style, detail, and depth of experience, but their themes and lessons are common. That period of idealism is now over.

But the commentary of Western decline is overheated. Militarily, the US is still the most powerful state on Earth by some distance. The two authoritarian states seen as potential rivals, Russia and China, may have formidable weaponry, but they are short of allies. The Soviet Union had a protective wall of communist-run states to the west and north—now, these states (with the partial exception of Hungary) are warily distrustful. China inspires fear not affection in its region, and while its neo-colonial expansion through the Belt and Road creates joint projects with cash-strapped states like Italy and Greece, neither country would prefer life in a China-dominated community of nations to their present membership of the EU. It’s heartening, but unsurprising, that nations which have a democratic order, no matter how imperfect and criticised, will prefer it to systems which lock up opposition figures, or which suppress whole peoples because they continue to follow a religion different from that of the state.

What is likely to have died—or at least been put into cold storage—is the approach which went by the name of “the responsibility to protect.” Developed after the genocidal atrocities committed in Rwanda and the Balkans in the 1990s, the UN General Assembly unanimously committed to use diplomatic, humanitarian, and other means to prevent or halt mass murder or ethnic cleansing. Force was not explicitly agreed—though Security Council authorisation under Chapter VII of the Charter could be used as a last resort, in the event of genocide and other serious international crimes. This was always a long shot, since any debate on intervention in the Security Council would generally meet the veto of Russia or China or both. But, for a while, it existed as a UN principle. Today, it is a dead letter. Those who saw the Iraqi and the Afghan interventions as a horror in their own right—in some cases, an even greater horror than the original reasons for intervention—have won the argument, at least until the next mountain of corpses.

For world leaders—and citizens—the experiences of Iraq and Afghanistan offer powerful reasons for staying at home and watching television reports of massacres and their results with comfortably inactive outrage. The failures of the US and its allies to “build nations” after the removal of despotism and mass murder has shorn the “responsibility to protect” doctrine of its moral force, as well as the popular backing its deployment requires.

In his book, The Lesser Evil, the Canadian writer and scholar Michael Ignatieff asked: “Why should democracies have anything to do with evil? ... the answer is that we are faced with evil people, and stopping them may require us to reply in kind … either we fight evil with evil or we succumb.” The decision to withdraw from Afghanistan returns those nations willing to fight evil to their couches, where they can sigh in safety.