George Orwell

There's (a Lot) More to George Orwell than Nineteen Eighty-Four

Orwell represents one of those strange cases where a writer’s reputation predominantly rests, if not on his worst, then certainly his least typical book.

It’s been more than 70 years since George Orwell (1903–50) published Nineteen Eighty-Four. Of his nine books (six of which were novels), it is by far the most famous and influential. In detailing his oppressively dark vision of social manipulation and political tyranny in late 20th century Britain, Orwell created a whole lexicon to describe the apparatus of totalitarianism—from “thoughtcrime” to “Big Brother.”

I actually find the softer, narcotized tyranny of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) to be a more subtle and accurate depiction of the way in which human populations are controlled today, even though Nineteen Eighty-Four is a more fully realized novel and has won greater acclaim. In his 2008 study comparing the world views of Orwell and Evelyn Waugh, The Same Man, David Lebedoff writes that “Nineteen Eighty-Four foretold what it would be like if Russia won the cold war; Brave New World described the future if the West did.”

Orwell represents one of those strange cases where a writer’s reputation predominantly rests, if not on his worst, then certainly his least typical book. Less than six months after its publication, Orwell died of tuberculosis at the age of 46, and thus the sense was reinforced that Nineteen Eighty-Four should be regarded as the crowning achievement of his writing life. This is a distinction which I don’t think it deserves.

His chilling little barnyard fable published four years earlier, Animal Farm, probes many of Nineteen Eighty-Four’s themes—most centrally, the collapse of even the best-intentioned socialist impulses into totalitarianism—but does so with more heart, humour, and purity of insight and (even though they’re animals) more fully developed characters than the later novel manages at three times the length. Throughout the writing of his final novel, Orwell was seriously ill, still mourning the death of his first wife, and living in social isolation on the Hebridean Isle of Jura. And it shows. There is a fevered unreality, an almost hysterical pessimism to Nineteen Eighty-Four that is occasionally repulsive and, well, downright Orwellian.

It’s not that Orwell’s literary world is ever a land of sunshine and smooth sailing. It can be a very shabby, second-rate world indeed. There are grubby and pungent details in Orwell’s writing that you’ll find in the work of none of his contemporaries—that spidery aspidistra plant that only increases the desolation of a barely furnished room; the smell of damp galoshes wafting through from the front hall (no author conjures up a wider panorama of bad odours); the black mottled pattern that forms in the neck of Worcestershire Sauce bottles that have been standing around a little too long; the fuggy cloud of Woodbine smoke that hovers over the queue at the Labour Exchange; the turd that floats atop the murky seawater that is flushed into the public baths where the boys of St. Cyprian’s boarding school seek to refresh themselves.

But no matter how cheap and desperate the depicted situations might be, there is almost always a core of decency in Orwell’s characters; an irreducible minimum of common sense, goodwill, and hard-won humour that might not redeem their world, but that at least allows these stubborn lugs to scrape their way through and live to fight another day. Listen here to the badly frazzled George Bowling who’s stumbling through a dreary middle age by plotting unattainable schemes of financial and marital fiddling. This hails from 1939’s Coming Up for Air, my own favourite of Orwell’s novels:

It’s a peculiar feeling I have towards the kids. A great deal of the time I can hardly stick the sight of them … At other times, especially when they’re asleep, I have a quite different feeling. Sometimes I’ve stood over their cots, on summer evenings when it’s light, and watched them sleeping, with their round faces and tow-coloured hair, several shades lighter than mine, and it’s given me that feeling you read about in the Bible when it says your bowels yearn. At such times I feel that I’m just a kind of dried up seed-pod that doesn’t matter two pence and that my sole importance has been to bring these creatures into the world and feed them while they’re growing. But that’s only at moments. Most of the time my separate existence looks pretty important to me, I feel that there’s life in the old dog yet and plenty of good times ahead, and the notion of myself as a kind of tame dairy cow for a lot of women and kids to chase up and down doesn’t appeal to me at all.

This also happens to be the 85th anniversary edition of my second favourite Orwell novel, Keep the Aspidistra Flying. (A quite faithful film adaptation was made in 1998 starring Richard E. Grant and Helena Bonham Carter and is well worth checking out if you can find it. (They witlessly rechristened it A Merry War for its North American release.) Aspidistra strikes even more disconcertingly conservative notes than Coming Up For Air, including a heartfelt pitch for the sanctity of life and the pro-life cause at a pivotal point in the main character’s redemption.

The book’s antihero, Gordon Comstock, is a failed poet with a rotten attitude toward bourgeois society, working in a mouldy used bookshop where he barks at any customer who dares break his focus as he scribbles out ill-tempered essays of socialist criticism for a Marxist rag called the Antichrist. The only thing that can break Comstock’s surly grudge against the world is when his on-again, off-again girlfriend announces that she’s nine weeks pregnant and will probably have to get an abortion because she knows she can expect absolutely zippo support from him. Rosemary’s pregnancy, in fact, turns out to be—not the wake up—but the grow-up call that Comstock has been assiduously dodging for years. He instantly realizes “that it was a dreadful thing they were contemplating—a blasphemy if that word had any meaning.”

Comstock ducks into a library to peruse a picture book of foetal development (arousing the disdain of the female librarian, who suspects Comstock’s interest is strictly pornographic), and his first instincts about the wickedness of abortion are swiftly confirmed:

He came upon a print of a nine weeks’ foetus. It was a deformed, gnome-like thing, a sort of clumsy caricature of a human being, with a huge domed head as big as the rest of its body. In the middle of the great blank expanse of head there was a tiny button of an ear. The thing was in profile; its boneless arm was bent, and one hand, crude as a seal’s flipper, covered its face—fortunately, perhaps. Below were skinny little legs, twisted like a monkey’s with the toes turned in. It was a monstrous thing, and yet strangely human. It surprised him that they should begin looking human so soon. He had pictured something much more rudimentary; a mere blob of nucleus, like a bubble of frog-spawn.

It’s not the sort of narrative tone that is popularly associated with Orwell. And yet, the only one of his novels that utterly lacks this element is Nineteen Eighty-Four. It’s a tone that expresses humility, generosity, and forgiveness; and it pervades virtually all of his magnificent and comparatively neglected books of non-fiction as well. Down and Out in Paris and London is a bum’s eye view of the European Depression. Homage to Catalonia recounts his involvement with the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War; and The Road to Wigan Pier passionately chronicles industrial poverty in the north of England.

Regarded as a marginal writer for nearly all of his career, Orwell had always experienced the writing life as a grinding struggle. One of my favourite of his essays—Books vs. Cigarettes—recounts the hard choice that every nicotine-addled bibliophile occasionally faces: to feed your addiction or your passion when you don’t have enough money to cover both.

Fifty years ago, Malcolm Muggeridge wrote of having thought of Orwell “as being, like Don Quixote, a ‘Knight of the Woeful Countenance.’” Ruminating on the irreligious Orwell’s admission that he had a real fondness and concern for the "Sancho Panza" who resides in us all—that low-functioning slug-a-bed who’s perfectly content to let the world rattle along any old way that it likes so long as it leaves him alone to catch up on his sleep and indulge a few mostly harmless pleasures—Muggeridge regarded Orwell himself as Sancho Panza’s much more diligent master: “There was in him this passionate dedication to truth, and refusal to countenance enlightened expedience masquerading as it; this unrelenting abhorrence of virtuous attitudes unrelated to personal conduct.”

With Orwell’s heart ever aligned with the struggling underdog, it is small wonder that his earliest political sympathies and instincts were socialist. But because of his unflinching commitment to describing things as they are in the plainest possible language, he inevitably began to call out the seemingly inbuilt socialist propensity to override the dignity of each individual for the sake of the common good … and thereby resort, sooner or later, to heavy-handed coercion and barbarism. Such insights did not endear Orwell to his lefty contacts in the politically insular publishing world, and they dropped him from their lists for deviating from the approved script. (Sound familiar?) He was eventually able to cobble together another circle of contacts, but Orwell never knew anything approximating security as a writer until the very last year of his life, when the Book-of-the-Month Club chose Nineteen Eighty-Four as one of its selected titles and he finally started to rack up the sort of sales he deserved.

Within 20 years following his death, Orwell had attained that untouchable stature that he retains to this day as one of the untainted giants of 20th century letters; a kind of secular saint whose moral imprimatur is continuously sought for the ideals put forth by advocates on all sides of important political and moral debates. If you can credibly claim that you’ve got the ghost of George Orwell in your corner, then, the thinking goes, you must be advancing an honourable position.

Orwell married Sonia Brownell in a hospital bedside ceremony three months before his death. He’d gotten to know her when she worked as an editor at Cyril Connolly’s Horizon magazine, and knew he could entrust her with the shrewd management of his now significant literary estate as well as the care of his adopted son, Richard. Orwell dared to hope that he might recover sufficiently that he and Sonia would be allowed to eke out a year or two together before the final curtain descended, but this was not to be. He couldn’t even leave the hospital for his own wedding reception dinner; let alone a honeymoon. One of the most poignant details of his final days was the brand new, never-used fishing rod propped up next to his hospital bed just in case things took a turn for the better.

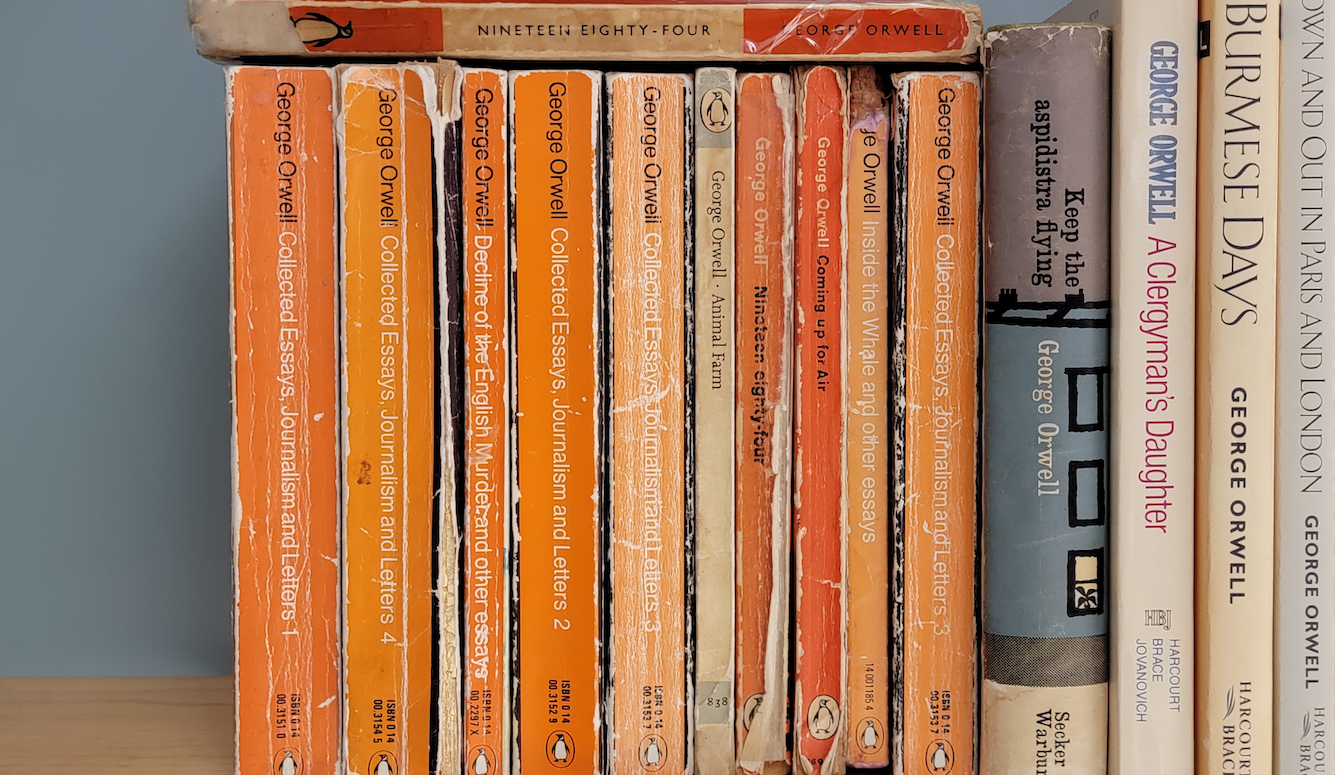

Perhaps Sonia’s greatest service to literature was heading up the team that pulled together and edited the four-volume edition of The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters that was first published in 1968. Simultaneously she also oversaw the publication of two shorter volumes that featured the most accomplished essays from that set: Funny but Not Vulgar and My Country Right or Left.

In addition to highlighting such highly regarded Orwell essays as Why I Write, How the Poor Die, and Politics and the English Language, these collections also feature some of his most beloved lighter essays, such as his anthropological study of the world of Billy Bunter and the Greyfriars Academy in his essay on Boys Weeklies, or his celebration of bawdy seaside postcards in The Art of Donald McGill. In essays such as these, Orwell broke with all the literary and critical conventions of the time by paying serious attention to lower-class entertainments that no other writer would’ve given anything more than a passing disdainful sneer.

One of the slighter essays Sonia collected was Some Thoughts on the Common Toad. This cheerful celebration of spring captures Orwell’s unsinkable humanity about as well as anything else he wrote, and seems a suitable note on which to conclude this invitation to check out the more human side of one of the world’s most celebrated, if (as I would insist) only partially appreciated writers:

How many times have I stood watching the toads mating, or a pair of hares having a boxing match in the young corn, and thought of all the important persons who would stop me enjoying this if they could … The atom bombs are piling up in the factories, the police are prowling through the cities, the lies are streaming from the loudspeakers, but the earth is still going round the sun, and neither the dictators nor the bureaucrats, deeply as they disapprove of the process, are able to prevent it.