Activism

Rescuing the Radicalized Discourse on Sex and Gender: Part Two of a Three-Part Series

Our choice of words affects the way we think. That’s why we spend so much time fighting over which terms to use, whether it’s “undocumented immigrants” versus “illegal aliens,” “foetuses” versus “unborn babies,” or “militants” versus “terrorists.” In recent years, the question of word choice has figured prominently in the activism of gender supremacists (as I described them in the first entry in this essay series), who seek to entirely replace biological sex with self-identified gender as a legal category.

According to the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, a priest’s blessing transforms the material substance of communion wafers and wine into the actual body and blood of Christ, even as the wafers and wine retain their outward appearance. Gender supremacists have a comparable doctrine—let’s call it transgenderation—by which the faithful must believe, literally, that “transwomen are women.” (It also demands that transmen are men, though it’s interesting to observe that the male-identified half of the trans community isn’t nearly so strident in its insistence on transgenderation as the female component.) I am not speaking figuratively here: A leading trans scholar at Berkeley, Grace Lavery, has claimed that (in the words of the university’s own headline writers) “truly changing sex is possible.”

As someone who has lived the internal politics of the LGBT community for decades (being of the G persuasion), I’ve noted that many of the gender-supremacist movement’s most doctrinaire high priests are trans women who, notwithstanding their loud and proud self-identification, seem quite happy with their penises and chest hair. Their Internet acolytes typically consist of mostly straight, bi, or queer-identified young people who are eager to sign on to what seems like a progressive movement. The priests aren’t elected, nor do they seem to represent the bulk of transgender individuals (who generally have a more realistic understanding of how biology works). However, the priests have been able to maintain their influence, and protect themselves from criticism, through word games and the threat of quick-trigger transphobia accusations.

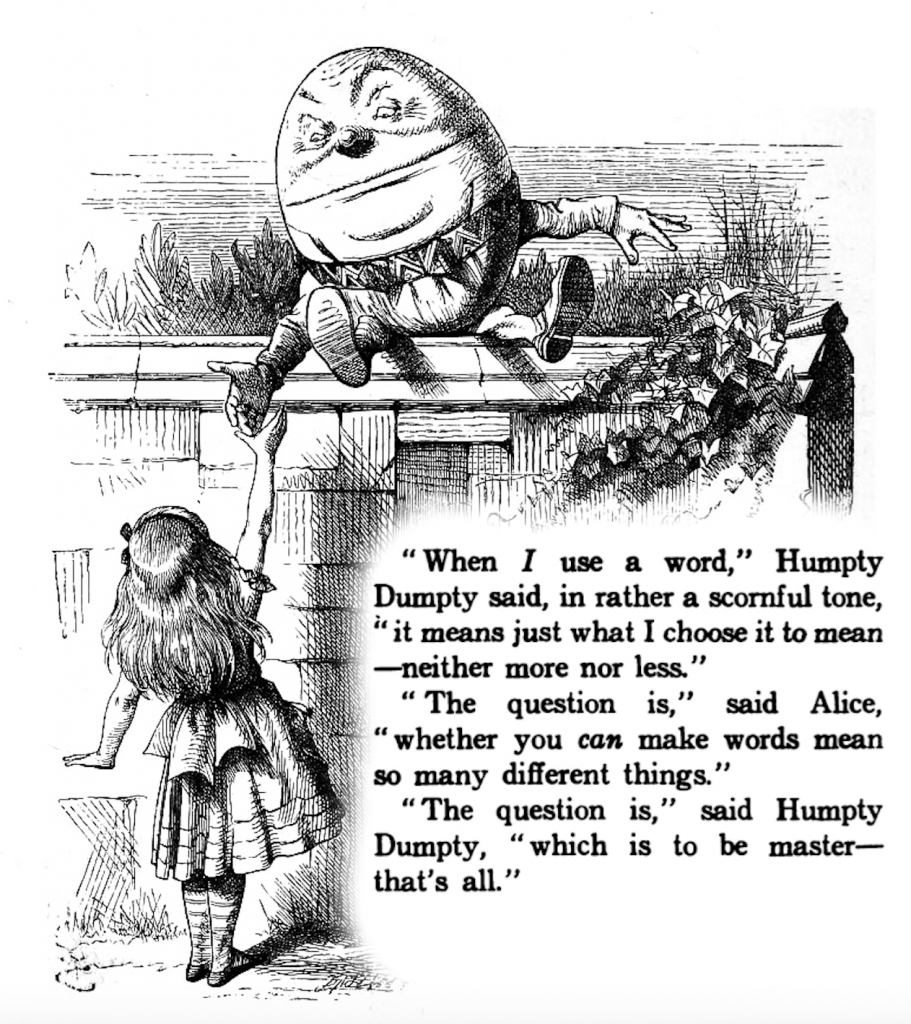

But you don’t have to understand Catholic doctrine to know how this game works. The Looking-Glass world of Lewis Carroll is good enough:

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.”

“The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

“The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master—that’s all.”

Humpty Dumpty’s will to power is instructive here, because the public discussion about trans rights, in most cases, is no longer about being kind and respectful toward trans people—a principle that everyone of goodwill now generally agrees on. Rather, it’s a project aimed at manipulating language as a means toward mastery in areas of policymaking where the rights of transwomen (in particular) conflict with other rights, including those of women who seek to keep their intimate spaces free of male-bodied individuals; and parents who feel that their children are being pressured to use transition as a means to deal with unrelated traumas or psychological conditions.

The word we once used to describe the men (as most of them were) who experienced gender dysphoria was transsexual. And while transsexual individuals were obviously part of the LGBT community in earlier eras, they were a small part, as the (physical) barriers to entry were considerable, and trans status wasn’t thought to be based on a simple act of self-declaration. (The Amsterdam Gender Dysphoria clinic, which has treated the vast majority of Dutch transsexuals for decades, reports that physically transitioned transsexual women account for only about one in 10,000 men, and physically transitioned transsexual men account for only about one in 30,000 women.)

In 1991, German sexologist Volkmar Sigusch created terminology to describe the 99.9+ percent of men and women who were comfortable with their birth sex: “cis” or “cissexual” (zissexuell in the original German). Since then, “cis” has migrated from a description of sex, and now is more commonly used to describe internally felt gender identity. Indeed, it is now routine for progressive educators to instruct children that they may be cis or trans in the same way that they may be gay or straight.

Since cis and trans are presented as adjectives, they apply equally to the nouns they modify—much like tall or short, heavy or thin. Thus, a man can be a man with a penis, or a man with a vagina, just so long as you put the right syllable (“cis” or “trans”) in front of the word “man.” This linguistic transformation has altered the meaning of words such as “man” and “woman” in a way that the adjectives “gay” and “straight” never did. It also allows radical gender activists such as ACLU lawyer Chase Strangio to emit such mantras as “Women and girls who are trans are biological women and girls.” As Humpty Dumpty might explain to a confused Alice: since genitals are irrelevant, and everyone has a biology, transwomen must be biological women.

A related consequence is that the term “birth sex” now has no meaning. That’s why it’s currently being replaced by the awkward “sex assigned at birth.” After all, if boys and girls aren’t identified by their penises and vaginas, we can’t say what they are until they tell us. (The term originally was used to describe babies with actual intersex conditions, who account for only a tiny percentage of births.)

These word games are politically useful: If the sex binary doesn’t exist, not only are the terms “man” and “woman” de-sexed, but the concept of transsexualism disappears as well. This is handy for the self-described transwomen who don’t actually suffer any kind of gender dysphoria (i.e., unease at a mismatch between sex and gender identity)—a male-bodied constituency that accounts for much of the activism in this area. After all, if bodies don’t matter, neither do the sex reassignment surgeries that draw attention to the definitional importance of male and female body parts. This explains, among other things, why transsexuals who continue to define themselves as such are seen as collateral damage to the gender-supremacist cause.

What we are left with is an imposed system of language that has no connection to physical reality, or to the “lived experience” of anyone except the tiny subset of a subset that created it. In Orwellian fashion, these activists have locked in their favoured dogma by defining the applicable terminology in such a way that dissent is rendered impossible.

This lurch into the Looking-Glass world is presented as the height of progressive enlightenment. But it’s the opposite: For over 60 years, I watched the LGBT and women’s movements separate the concepts of sex and gender, so that effeminate boys (“genderqueer” or “gender non-conforming,” in modern parlance) could grow up to be Quentin Crisp, and girls could be Fran Liebowitz, all without judgment and harassment. The more avant-garde approach, on the other hand, erases the real distinction between sex and gender by demanding that the former be subordinate to the latter. But of course, gays, lesbians, and bisexuals experience same-sex attraction on the basis of real biological sex, not the abstraction of gender.

That attraction is foundational to our lives and self-understanding. Yet it is systematically denied by gender supremacists, who are incapable of reconciling their claims about human identity except through the fiction that humans are sexually attracted based on the gender self-identification of potential partners. (To give up this claim would be to admit that a lesbian isn’t going to be attracted to a male body, no matter how many times she is assured that the body in question belongs to someone who identifies as a woman.) The LGB population, in other words, has effectively been gaslit to fit the ideological convenience of a subset of trans activists—a deeply homophobic project.

Far from speaking for the entire LGBT community, gender supremacists don’t even speak for many trans people. They certainly don’t speak for trans pioneers such as cross-dresser Virginia Prince (a self-identified heterosexual man), or drag kings and queens such as Stormé DeLarverie, who realized that their creative and non-traditional ideas about gender didn’t alter their underlying sex. Nor do gender supremacists speak for trans heroes such as Aimee Stephens, a Michigan funeral director whose case went to the US Supreme Court. Stephens had been fired by her employer precisely because her gender identity didn’t align with her actual sex. (The funeral home allowed women to wear skirts, but refused Stephens’s request to do so on the basis of her male biology. In other words, sex discrimination was at the centre of the case and the basis of her victory.)

Nor do gender supremacists speak for transsexuals such as veteran activist Buck Angel, who self-describes as “born biologically female.” (“I use testosterone to masculinize myself so I feel more like me,” he has written on Twitter. “I had a legal sex change and now live as a male. All male pronouns. I am a transsexual and will never be biologically male. But I do live as a male.”)

I was born biologically female. I use testosterone to masculinize myself so I feel more like me. I had a legal sex change and now live as a male. All male pronouns. I am a transsexual and will never be biologically male. But I do live as a male. Simple. ❤️Tranpa pic.twitter.com/nNuV9Kxd5d

— Buck Angel® (TRANSSEXUAL MAN) (@BuckAngel) December 23, 2019

“The whole point to my transition was to be seen as a male, live as a male, but to always be honest about where I came from,” Buck told me. “I’m a biological female and that truth is what this new ideology is trying to eliminate, along with the understanding of dysphoria. To say you are a non-dysphoric trans person makes zero sense. It’s very insulting to the people who actually struggle with gender dysphoria. We’re getting bashed by this new ideology. Not sure how can they come in and completely coopt our identity, then act all insane when we fight to keep it.” (Angel’s 2020 Quillette podcast interview may be found here.)

Debbie Hayton, a trans British high school physics teacher, also has taken a public stand for the reality of biology. “Transsexualism is a response to a psychological condition, and transition is something we did to improve our mental health,” she argues. “We’re trans because we did something. Our response and experience are being used by others to ‘validate’ their identities, whatever that means. This frustrates me, because while I can make the distinction between transsexual and transgender others don’t.”

Kay Brown is a transsexual activist who transitioned to a female identity four decades ago, and the author of a must-read article entitled How the Big Tent Transgender Movement Distorts Science and Holds Back Civil Rights for Transsexuals. She says that even the very word she uses to describe herself, “transsexual,” is now employed as a term of abuse by self-described transgender activists who (unlike Angel, Hayton, and Brown) don’t actually experience clinical gender dysphoria. She also describes being dismissed as “truscum,” (which Urban Dictionary defines as “A queer individual [who] holds the belief that you require gender dysphoria to identify as transgender”).

Brown equally dislikes being misidentified as transgender. “The first time I got called ‘transgender’ by a doctor, in 1996, I almost bit his head off,” she says. “I wanted to scream. Up to the 1990s, transgender meant straight men who role-played as ‘girls’ on ‘girls night out’ at the local gay bar mid-week when [business] was slow enough that the management tolerated their presence. Two transsexual friends mistakenly went to such an event. ‘Close your eyes. What do you hear?’ ‘A bunch of straight men talking loudly.’ ‘Right, we don’t belong here. Let’s go.’”

Trans people deserve to be able to self-identify and self-understand as they wish. But everyone else has the same right—including women who lack the privilege or entitlement to trivialize their sex as a badge of identity. Their self-understanding as women is centred on the biological urgency of pregnancy, miscarriage, childbirth, menstruation, and menopause; and (even if they go through life without experiencing some or all of these events) bodies that are evolutionarily programmed to accommodate these processes. Their fight for the right to vote, work, drive, enter into contracts, and control their own bodies emerged from this reality, which also has included such sex-specific horrors as genital circumcision, sex slavery, menstrual huts, rape, honour killings, and live burial and burning upon widowhood. The refusal of gender supremacists to allow women the language of their bodies and historical experience is brutal. It is also deeply hypocritical, given the emphasis trans activists typically place on the idea that language can serve to oppress or even “erase” someone.

A woman working within the medical bureaucracy here in Canada reports to me: “When I’m working on perinatal guidelines, I’m told that the word ‘woman’ isn’t safe for trans people. We’re told to use ‘chest feeding’ and ‘pregnant individual,’ never breast or women. I think we should be gender inclusive rather than gender neutral. Transmen are maybe .001 percent of people who give birth. We should be welcoming, but we shouldn’t direct all our energies to their issues and away from the issues that affect women giving birth.”

It may be tempting to dismiss this as mere political correctness—a harmless attempt to err on the side of sensitivity. But these linguistic choices reflect the very real demands of trans activists to pretend away the biologically rooted differences between men and women. Influential American trans polemicist Julia Serano, for instance, seems genuinely mystified, and even angry, at the lesbians who reject her male genitals as an object of sexual attraction. “If it were only a small percentage of cis dykes who were not interested in trans women at all, I would write it off as simply a matter of personal preference,” she wrote in 2017. “But this is not a minor problem—it is systemic; it is a predominant sentiment in queer women’s communities. And when the overwhelming majority of cis dykes date and fuck cis women, but are not open to, or are even turned off by, the idea of dating or fucking trans women, how is that not transphobic?” (For the record, Serano is also upset at trans men with vaginas: “Trans male/masculine folks who claim a place in dyke spaces by emphasizing their lack of male genitals or their assigned-female-at-birth status royally screw over their trans sisters.”)

“There’s a real lack of kindness and empathy about what we go through as lesbians,” a friend of mine told me. Like the woman working in a hospital, quoted above, and almost every other “cis” woman I’ve interviewed on this subject, she asked for anonymity. They now operate under the fear that stating certain obvious facts—for instance, that lesbians are attracted to vaginas and breasts, not penises—will lead to being mobbed on social media and possibly even fired from their jobs.

The idea of “safety” is never far from the surface in these discussions—a common feature of moral panics, which always are animated by the belief that heterodox opinions could endanger human life. “Public safety” was behind the puritanical laws that kept gays and lesbians in the closet. For LGBT organizations to weaponize this kind of rhetoric today is an insult to the community they serve. It also makes us look ignorant and oversensitive, given that LGBT communities in other parts of the world are fighting for basic rights in the face of state-sponsored torture and killing, and so don’t have the luxury of complaining about not being lusted after by, as Serano puts it, “cis dykes” or their male equivalents.

***

As an adult, I discovered that 10 percent of my high school and university residence friends were gay. Each of us thought we were alone because we were afraid to reach out. I see parallels when it comes to today’s intellectual closet: People are afraid to say what they think, even when it comes to obvious facts concerning their own biological makeup and sexuality.

At the same time, many of the loudest voices in the LGBT activist (and “allyship”) community are only nominally queer, their ranks being padded with legions of allegedly bi women and their boyfriends, who simply role-play, experiment, fantasize beyond the vanilla, and grab attention by writing about their queer haircuts. Now a casually assumed identity, “Queer” once was the gay N-word—the last word many gay men heard as they were beaten and killed. Many of us reclaimed it during the AIDS pandemic—“We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it”—and then continued to use it as a synonym for gay (especially when discussing our community in a political context). Its increasingly watered down usage by bourgeois dilettantes represents an offensive trivialization of our history.

In 1999, Kimberly Peirce directed the ground-breaking film Boys Don’t Cry, which, for the first time, brought the issue of anti-trans violence to a mainstream audience. Even today, studios rarely back female directors. Back then, Peirce’s path was even harder—especially given her identity as a non-binary lesbian who wanted to make a movie about people whom many people considered freaks. But after years of effort, Peirce’s dedication paid off. Her film won a slew of awards and attracted widespread support to the trans cause.

In 2016, however, queers at Reed College in (where else) Portland tore into her at a campus presentation. Why? Because she’d cast the non-trans actress Hilary Swank as pre-op Brandon Teena. Placards read: “Fuck Your Transphobia!,” “Fuck this cis white bitch,” and “Fuck you scared bitch.” Some arts journalists even cheered them on, arguing that change was needed so that “transgender people won’t feel their only recourse is to label a celebrated queer filmmaker as a bitch” (my italics).

Or consider Martina Navratilova, one of history’s great tennis stars, who lost millions in endorsements as an out lesbian in the 1980s. A lifelong campaigner for equal rights, her trainer was trans pioneer Renée Richards. But when a late-transitioning Canadian trans academic then going by the name of Rachel McKinnon (since rebranded as “Veronica Ivy”) began winning women’s cycling races a few years back, Navratilova tweeted: “You can’t just proclaim yourself as female and be able to compete against women.” She clarified in the Times: “I am happy to address a transgender woman in whatever form she prefers, but I would not be happy to compete against her. It would not be fair.” Twitter went full Inquisition, and Navratilova was blackballed as a bigot by the LBGT charities she’d worked for, a humiliation broadcast in the mainstream press and now the only safe opinion on progressive social media.

We now live in a world where even RuPaul—drag’s grande dame since the 1990s, who made drag mainstream through RuPaul’s Drag Race—can be denounced as a reactionary. In 2018, RuPaul noted that drag’s power is based on the inversion of sex roles, and “loses its sense of danger and its sense of irony once it’s not men doing it, because at its core it’s a social statement and a big F-you to male-dominated culture.” This is why, RuPaul explained, he never cast trans women as drag queens. “You can identify as a woman and say you’re transitioning, but it changes once you start changing your body. It takes on a different thing; it changes the whole concept of what we’re doing.”

RuPaul was denounced by twenty-somethings as a transphobe who didn’t understand drag. He responded like any great queen: “You can take performance-enhancing drugs and still be an athlete, just not at the Olympics.” The response was consistent with his unapologetic stance during an earlier controversy, when he’d brushed off activists’ complaints about his gender-bending wordplay: “We take feelings seriously and intention seriously, [but] if you are trigger-happy and looking for a reason to reinforce your own victimhood, your own perception of yourself as a victim, you’ll look for anything that will reinforce that.” By 2018, however, offending the trans lobby had become more radioactive. Facing brand meltdown, RuPaul apologized, and called his critics “my teachers.”

In Canada, they came for Sky Gilbert, co-founder and artistic director of Buddies and Bad Times Theatre, the largest LGBT theatre in North America during the 1980s and 1990. As he described to Quillette readers in 2019, the company had planned a staged reading of his 1986 hit play Drag Queens in Outer Space as part of its 40th anniversary celebrations. But when self-described Trauma Clown Vivek Shraya attacked gay men in her 2018 book I’m Afraid of Men, Gilbert wrote a response on his blog, which he titled I’m Afraid of Woke People. Shraya herself had no comment, but queer heresy-hunters accused Gilbert of racist violence against the trans community. Buddies denounced him, and replaced the reading with a three-and-a-half hour struggle session. So it came to pass that Sky Gilbert, who fought for minorities and hired trans folk before Shraya was born, became persona non grata at the company he’d founded.

Woke doctrine holds that the feelings of individuals from marginalized groups should act as a checkmate on further discussion, lest they suffer trauma or emotionally experienced “violence.” But whose feelings count within these groups? Peirce is a butch lesbian who broke pink and glass ceilings. RuPaul is a gay black kid who overcame poverty, sexual trauma, and drug abuse. Navratilova is an immigrant lesbian. Gilbert is a drag queen.

Perhaps nowhere is the totalitarian push to silence dissent on the subject of gender more evident than in the campaign to demonize lifelong LGBT ally and advocate J.K. Rowling as a transphobe. The mobbing began in earnest in 2019 after Rowling tweeted: “Dress however you please. Call yourself whatever you like. Sleep with any consenting adult who’ll have you. Live your best life in peace and security. But force women out of their jobs for stating that sex is real?” She was referring to Maya Forstater, a British woman who’d lost her job for tweeting that, owing to biology, she believed trans women were men. Forstater had appealed to an employment tribunal, and a judge had ruled against her. (Last month, that judgment, in turn, was overturned by a High Court in a decision that tore the tribunal judgment to shreds.)

Dress however you please.

Call yourself whatever you like.

Sleep with any consenting adult who’ll have you.

Live your best life in peace and security.

But force women out of their jobs for stating that sex is real? #IStandWithMaya #ThisIsNotADrill— J.K. Rowling (@jk_rowling) December 19, 2019

In a subsequent essay, Rowling underlined both her support for trans women, but also her support for women’s sex-based privacy rights, speaking as the survivor of a violent sexual attack. She explained, “I believe the majority of trans-identified people not only pose zero threat to others, but are vulnerable for all the reasons I’ve outlined. Trans people need and deserve protection … I want trans women to be safe. At the same time, I do not want to make natal girls and women less safe. When you throw open the doors of bathrooms and changing rooms to any man who believes or feels he’s a woman—and, as I’ve said, gender-confirmation certificates may now be granted without any need for surgery or hormones—then you open the door to any and all men who wish to come inside. That is the simple truth.”

The detail that many critics missed (or claimed to miss) was that Rowling wasn’t speaking about any danger from trans women. Rather, she was discussing the danger that the policy of unfettered self-identification poses to women, insofar as it may be taken advantage of by predatory men posing as trans. People (of all types) have assumed false identities since Jacob tricked Isaac and Odysseus returned to Ithaca disguised as a wandering beggar. Every week, another case of race-shifting is exposed. Why should gender self-identification be uniquely free of grift?

Yet two years later, hatred of Rowling remains de rigueur in progressive LGBT circles. Eddie Izzard, the once-transvestite comic was cheered in December when she came out as trans with she/her pronouns. But baby queers told her to “do better” in January when she came to Rowling’s defence, notwithstanding that Izzard was already wearing frocks when their parents were in grade school.

The point at which the trans activist cause became so radicalized that it put itself in opposition to feminism and gay rights is hard to identify with precision. But according to Hayton, it was when mere self-identification was taken as the gold standard of who was a man and who was a woman—a policy that’s become encoded in law in many jurisdictions over the last decade. Once that proposition was embraced, all of the other outrages followed: biological men competing in women’s sports, violent male criminals suddenly self-identifying as women so they can do their time in female prisons, and fully intact men proudly taking photos of themselves in women’s bathrooms. “There was widespread acceptance of transsexuals in women’s spaces when I transitioned in 2012,” says Hayton. “But the assumption was that you’d changed your body or were going to, and this was a response to a medical condition. Moving it from a medical to a social issue has damaged our acceptance. If pre-op trans women are let in, how do you stop any male person who claims to be some sort of woman.”

There is much basis for solidarity among gays, lesbians, and trans people. Decades ago, we were the ones being subject to psychiatric evaluations, and stigmatized with the label of mental illness. We, too, were accused of being sexual predators who could not be trusted in washrooms (and may other places besides). But we met the charges honestly, not by tricks of language or countervailing hate campaigns against our critics.

When today’s gender priesthood refuses to engage even good-faith LGBT allies, they abdicate the moral high ground and lose all credibility. Unable to persuade, they resort to bullying. Such aggressive tactics have allowed them short-term success in academia, arts, government, and NGO circles, where employees and administrators fear the professional consequences that go with ideological heterodoxy. But this success has come at a price, as there is now a large and growing group of disaffected progressives, LGB and otherwise, who see militant trans activists not as allies, but as political liabilities who have hurt our cause—right down to the language we use to describe our very being.

Allan Stratton is the internationally award-winning author of Chanda’s Secrets and The Dogs.

Featured image: RuPaul in 2007