Culture Wars

The Accomplishments of Black Conservative Thought

As a black conservative man, I will add one final note. None of the points made in this essay—about the over-hyping of victimhood in modern America or the cultural issues in working-class black and white communities—is meant to imply that racism does not exist.

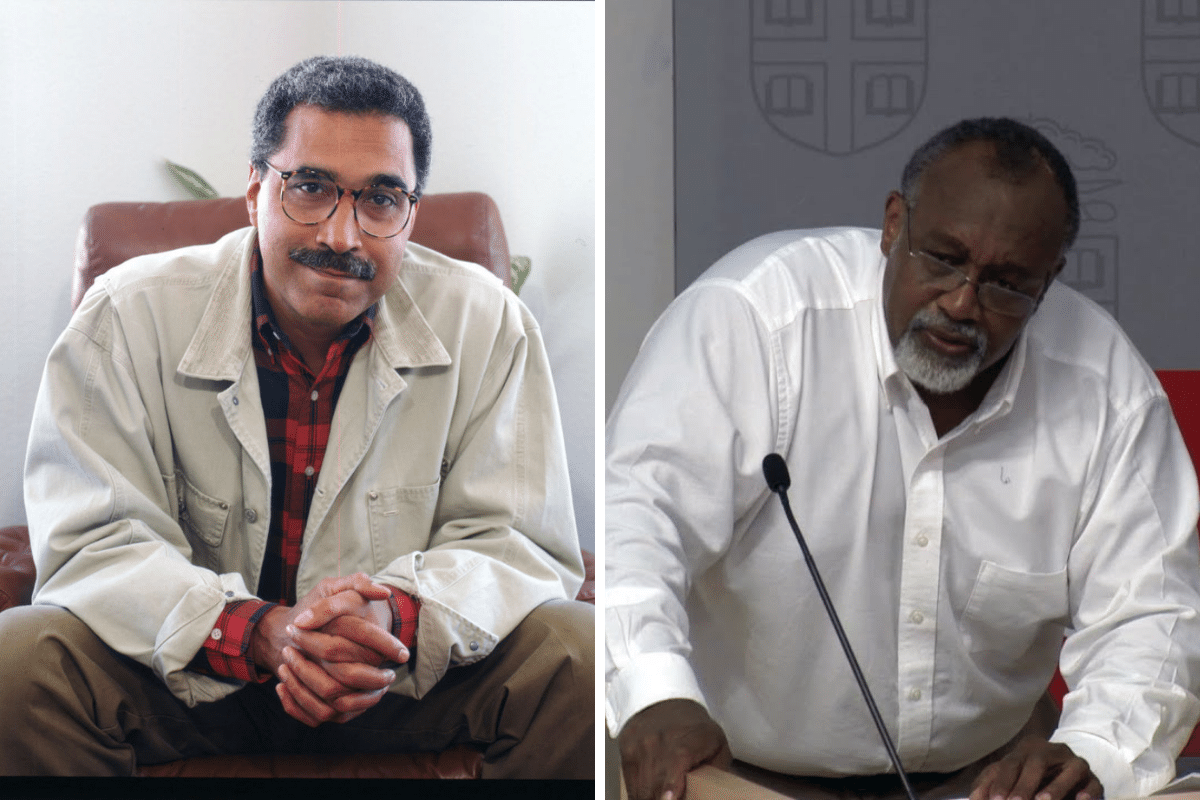

The line between moral and empirical claims is a tricky one for debaters. In his thoughtful Quillette essay, “The Limitations of Black Conservative Thought,” Aaron Hanna—like me, a professor of Political Science—critiques some of the more sweeping theoretical claims of America’s intellectual tradition of black conservatism. However, he does not rebut (or necessarily attempt to rebut) many more empirical points made recently by scholars like Thomas Sowell, Glenn Loury, and indeed myself.

To a large extent, Hanna’s essay is a critical analysis of imperfect visions. He notes that the US black conservative tradition is often defined by two primary paradigms: Shelby Steele’s idea that an attraction to the idea of “victimhood” is thwarting black progress and Sowell’s idea that there are problems in “black culture” that limit competitiveness. Both men advocate personal responsibility and choice as the most reliable path to black advancement. In contrast to these visions, Hanna accurately notes, the dominant paradigm on the progressive Left is that oppression, or “systemic racism,” limits African American performance.

Hanna’s essay identifies several flaws in all three paradigms. He points out that what Steele calls the individual’s “margin of choice” is extremely limited. People do enjoy a degree of what might be loosely termed “free will,” but one cannot simply choose to have a loving father at home. However, Hanna downplays empirical arguments made by contemporary black conservatives about the effect of cultural variables and perceptions of risk on outcomes, as well as the important role of black conservatism in empirically rebutting claims of systemic racism.

Obviously, a kid raised in a single-parent home in a decaying neighborhood will encounter problems besides an internalized sense of victimhood. However, heterodox thinkers have repeatedly pointed out that many leftist and black Americans do hold a range of wildly untrue beliefs about the nature of “racial oppression” that are likely to hamper success. A recent study from the Skeptic Research Center (SRC) found that 31 percent of those identified as “very liberal” on an ordinal survey believe that the average number of unarmed black Americans killed annually by police is “about 1,000.” Fourteen percent believe that this number is “about 10,000,” while almost eight percent believe it is more than that. To put this astonishing finding in context, less than 20,000 homicides of any kind take place in a typical year, about half of which involve blacks. The total number of unarmed black men shot by police in 2020 was 18.

The SRC’s finding was not an outlier. During the same year, the political scientist Eric Kaufmann found that 80 percent of American blacks and 60 percent of college-educated white liberals believe that more young black men are shot annually by police than die in auto wrecks. In reality, there are roughly 40,000 fatal car wrecks annually, concentrated among younger drivers, and roughly 1,000 fatal cop shootings, fewer than 250 of which involve blacks.

Paranoia about the threat to black safety posed by whites is hardly confined to discussions of policing. A remarkable 2005 article in the Washington Post reported that more than 25 percent of black Americans believed AIDS was created in a government lab, 15 percent saw the disease as a form of genocide against blacks, and 12 percent thought it was originally created and spread by the CIA. While such beliefs are obviously not the only thing preventing black advancement, it is difficult to imagine those who hold them participating whole-heartedly in society alongside those they see as genocidal oppressors. Steele is correct if sometimes excessive in making this point, and a robust black conservatism does discourse a substantial service by actively fighting such misinformation.

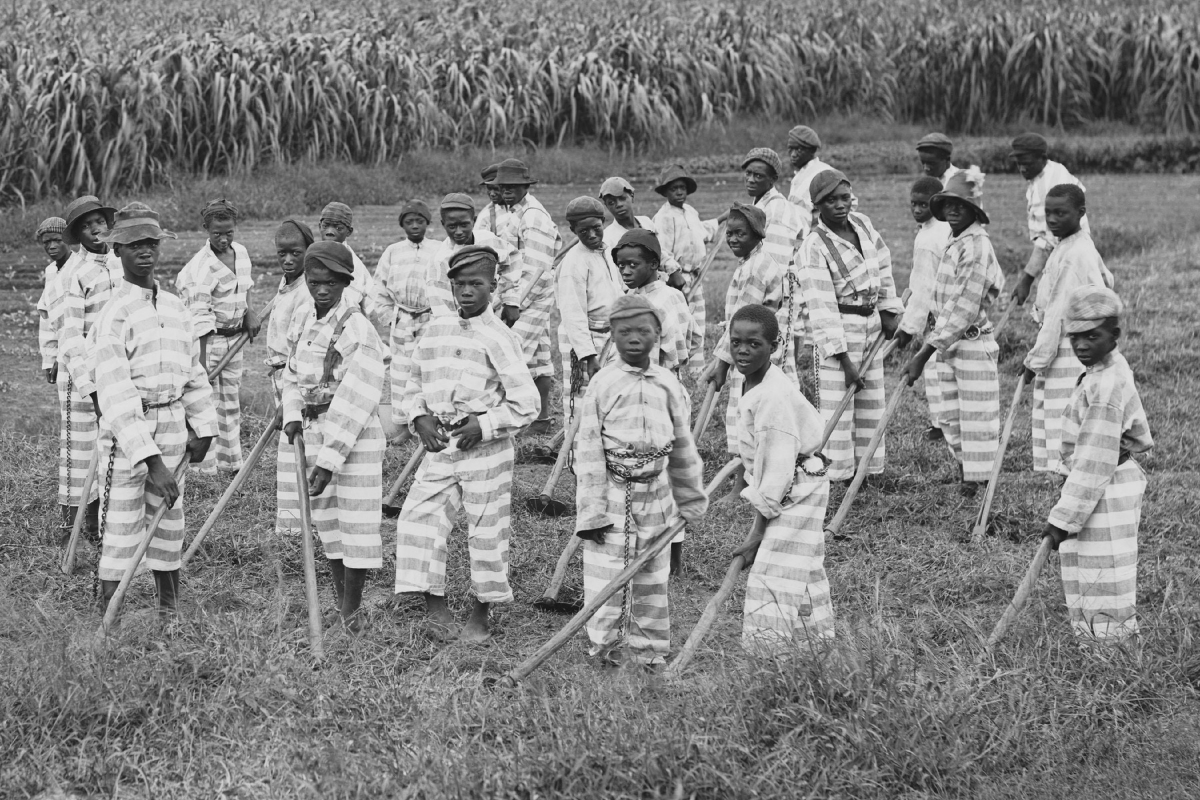

Reasonable criticisms can also be made of black conservatism’s sometimes unsympathetic view of black culture. It is certainly worth asking, for instance, whether widespread fatherlessness really can be traced back to the historic “hillbilly” neighbors of black Americans (a hypothesis forwarded by Thomas Sowell that Hanna treats with incredulity), rather than to the legacy of racial oppression. If Sowell is correct, why did out-of-wedlock birth rates only really begin to surge during the 1970s? These are interesting conversations, outlined well by Hanna, and I participate in them.

BUT. It has been heterodox minority thinkers like Sowell, Walter Williams, Glenn Loury, John Sibley Butler, John McWhorter, John Ogbu, and Amy Chua—with June O’Neill perhaps the sole left-trending white outlier—who have pointed out that adjusting for specific cultural/situational variables largely explains contemporary racial gaps in performance. Both O’Neill and Sowell have argued that adjusting for factors like region of residence, family structure, average age—the most common age for a black American is 27 compared with 58 for a white American—and aptitude test scores almost totally closes black-white gaps in income. Ogbu and Chua have made similar points about the obvious, but rarely discussed, correlation between study culture and test scores. Even conservative pundit Dennis Prager—admittedly another white guy, but one who has clearly read and built upon this literature—notes that father-absence measurably increases a white family’s chance of poverty to 22 percent, more than three times the chance currently faced by a two-parent black family (seven percent).

This development of contemporary quantitative culturalism is not an incidental “black conservative” addition to the academic and public intellectual literature. It is a major one: potentially a stake through the respective hearts of competing theories of systemic racism and genetic determinism, and at least a more-than-equal rival to either. Further, the existence of this baseline Sowell-and-Loury theoretical framework allows us to develop practical solutions to the problems of black and poor communities. A few examples might include: encouraging and funding charter schools as advised by Sowell (2020), strict enforcement of child support and child neglect laws, and the organized cross-media promotion of healthy behavior.

A final contribution of the black conservative paradigm as currently constructed has been the logical demolition of the primary rival paradigm. This Hanna-Loury-McWhorter-Reilly conversation in the pages of Quillette is essentially a friendly sparring match among heterodox intellectuals. Out in the wider world, the dominant explanation for group gaps is that these must be caused by some phlogiston-like variety of subtle bias, which has nothing to do with culture, interests, luck, genetics, or other variables. Increasingly, this is said openly. During an interview with Vox, Ibram X. Kendi declared, “[T]here’s only two [possible] causes of racial disparities. Either certain groups are better or worse than others … or racist policy. Those are the only two options, and antiracists believe that the racial groups are equal, and so they’re trying to change policy.” However, calculations such as Sowell’s empirically demonstrate that this is not the case. Pointing this out would be, to say the least, a valuable service even if black conservative quants had contributed nothing else.

As a black conservative man, I will add one final note. None of the points made in this essay—about the over-hyping of victimhood in modern America or the cultural issues in working-class black and white communities—is meant to imply that racism does not exist. In addition to gathering his data on racial misperceptions, Eric Kaufmann finds that something like 10 percent of Americans today would never engage in an inter-racial relationship, and widely cited recent data from Gallup reveal that eight percent of Americans would never vote for a qualified same-party presidential candidate who happened to be black. Shameful, to be sure.

However, broadening the analytical lens beyond whites and blacks, in a country that is now just 59 percent non-Hispanic white, reveals a different and more complex pattern. The same Gallup survey also revealed that nine percent of Americans would not vote for a Hispanic, nine percent for a Jew, 19 percent for a Mormon, and almost 40 percent for an Arab or other Muslim. Methodologically sophisticated audit-style studies often turn up similar results—a recent example found severe bias—an additional 28 percent rate of recorded rejection—against Asian job applicants with names like “Chiang” and “Suzuki” when compared to all applicants with Western names. Another study detected religious as well as racial bias, with applicants identifying as members of traditions including Catholicism and Wicca 29 percent and Muslims 38 percent less likely to receive a callback than control group members.

A bluff statement like “We all pick on each other, these days” may sound—and indeed may be—a bit sophomoric. But the plain fact is that, notwithstanding findings of enduring prejudice, seven or eight (depending on how you count South Africans) of the top 10 income-earning groups in the United States today are made up of people of color, with Indian Americans taking the top spot at more than $135,000 annually. This may be because of how these groups score on traits identified as critical to success by black conservatives and other quantitative culturalists: settling in areas associated with success, study culture, aptitude test results, and—perhaps especially—stable culture based around strong families. These things really do matter, it seems.

Aaron Hanna has performed a valuable service by recommending that black conservatives update some of their foundational definitions and concepts, and that they consider serious alternative explanations for phenomena such as those outlined in William Julius Wilson’s The Declining Significance of Race. Perhaps most notably, he reminds affluent thinkers across all ideological blocs to bring greater humility and sympathy to bear on their analyses. It may be true that a fatherless black boy in a tough Louisville neighborhood will have a significant affirmative action edge over a working-class white peer when and if he applies to college—but this message must be conveyed so that it reaches receptive ears and encourages application.

However, Hanna’s essay often neglects the purely empirical contributions of black conservative thought, including: pointing out the false nature of many prevalent beliefs about minority victimhood, illustrating the simple components of the actual pathway to success, and detailing the logical and empirical flaws undermining the explanatory power of systemic racism. While any analysis can and should be improved by debate, it is often the case that the body of heterodox black thought has more to offer to a young black—or indeed non-black—American than any similarly-sized corpus of contemporary ideas. That ain’t so bad.